Hi everyone!

Today I’m so excited to bring you the third and final installment of the story of Catherine de Medici, the much-maligned Renaissance queen of France. She is usually portrayed as a wicked poisoner and bloodthirsty murderer, but the reality is much more nuanced. I’m so excited dot unpack it with you here!

If you haven’t yet, listen to part one and part two before you dig into this final installment. It might not make a lot of sense without those. You can also check out the bonus episode related to Catherine de Medici: What Is Up With Italian Poisoners? Then come join our discussion thread about Catherine de Medici and pop culture and help us decide: Should we watch some of The Serpent Queen together?

Oh! And if you haven’t yet, come check out the first-ever Ask Me Anything that I’m hosting. Ask me anything about previous episodes, your burning history questions, or anything else. I’ll answer some questions here and some might become future bonus episodes!

All right, without further ado: Part three of the story of Catherine de Medici.

🎙️ Transcript

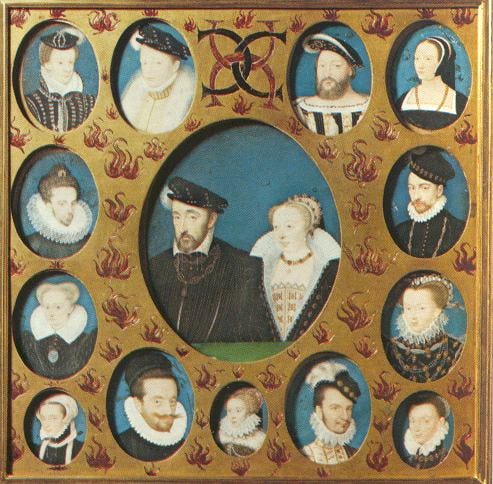

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m covering the third and final installment of my mini-series on the famous Queen of France Catherine de Medici. Though she’s had something of a mixed reputation for a few centuries now, recent historians have been doing a bit of reclamation of this polarizing queen. She’s remembered as a powerful leader and devoted mother but also as a poisoner and a central figure in the French Wars of Religion. For this episode I’m relying heavily on the 2003 biography of Catherine by Leonie Frieda, which I recommend checking out if you’re interested. It’s over 400 pages and goes into much more depth than I’ll be able to here.

But before we jump into Catherine’s life and how she became the most powerful woman in sixteenth-century France, I want to give a huge thank you to all the paying subscribers on Substack who make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t be possible without you! If you want to support Unruly Figures and my mission to make interesting history free, you can do that at unrulyfigures.substack.com Becoming a paying subscriber will also give you access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes info on the podcast.

All right, let’s hop back in time.

When we left off, it was 1567 and Catherine’s final hopes of peaceful coexistence between Catholics and Protestants in France had finally been dashed as the second War of Religion kicked off. A blockade had been established around Paris, ensuring unrest, starvation, and fear reigned inside the city.

Catherine attempted negotiations, though she was quickly losing faith. Louis of Condé, Prince of Navarre, who was leading the Protestant rebels, had claimed that he was still loyal to Charles IX, the King of France, but was trying to, quote, “deliver the country from its present troubles.”1 The issue with this claim is that devout Catholics were not going to accept the existence–let alone toleration of–Protestants in France, full stop. Meanwhile, Protestants wanted full equality and rights, so there wasn’t really a compromise available. When one group will only be happy with the extermination of the other, there’s not a lot of room for negotiation, and Catherine quickly saw that reality.

Anne de Montmorency, who was now in his seventies and serving his fifth successive French king, rode out to lead the King’s 16,000-strong army.2 Unfortunately, he was killed quickly, and with him any hope of success for the royal family in this war. Catherine ordered a funeral for Montmorency with, quote, “such honours that it could almost have been mistaken for a royal interment.”3 He was laid to rest in Saint-Denis near the tomb of Henry II, the king he had served longest and most loyally.

Catherine installed her sixteen-year-old son Henri of Anjou, the heir apparent to the throne, as Lieutenant-General of the army, and assigned several military advisors. However, Henri was not particularly outdoorsy or interested in military anything–he had been, quote, “petted and surrounded by the Queen Mother and her women, living a cosseted life to protect his health, given specially warmed rooms, kept out of drafts and generally pandered to” until this moment.4 He did not cut a particularly inspiring figurehead, nor did he know what he was doing leading a military. Why Catherine did this can only be attributed to the fact that Henri was always her favorite son, and at sixteen he was probably begging for things to do. This move also really enraged Charles, who had wanted to lead the army as a warrior king but was clearly too physically weak to do so. Catherine biographer Leonie Frieda summed up this terrible decision by saying, quote, “conducting warfare by committee is always a risky undertaking, but when the committee was composed of feuding inadequates led by an effete teenager the risk seemed near-suicidal.”5

Let’s talk about Henri of Anjou for a second. His historical reputation is as maligned as Catherine’s, if not actually historically worse. He was accused of being ridiculous, obsessed with luxury, effeminate, and sexually deviant, more interested in the men he was closest to, known as the mignons, than any woman. When people talk about him desiring a woman at all, it’s his sister Marguerite, adding incest to the list. These are contemporary accusations–Marguerite talks about this in her own memoirs. Late in his life, he was addressed directly as “Henry of Valois, buggerer, son of a whore, tyrant.”6 He might have been bisexual, at least there’s plenty of contemporary evidence to support that, though a lot of that evidence is used to explain that he was a bad person and leader because he was attracted to men, which I draw the line at. From what I’ve read, it does seem like Henri was more interested in having a good time than doing any real work, and we’ll see a little bit of that here. Like his brothers, he was sickly, but not as bad as them–he lived much longer than any of his three elder brothers, and eventually died at the hand of an assassin, rather than the ailments that had claimed the rest of the Valois children. He was known as charming, lively, glamorous, and well-dressed–though he’s sometimes depicted as dressing too effeminately. Some even interpret this as cross-dressing.

Okay, so while Henri was getting his feet wet trying to lead an army he had no business leading, Catherine still attempted to negotiate for peace. She secretly met with leaders of the rebels, but word got out and Parisians began to turn against the royal family. Parisians had, more than anyone, sacrificed a lot–they had given money for the levying of troops, had been heavily taxed besides, and now were suffering the effects of the blockade. Paris was also a bastion of intense Catholicism as well, and they were loudly calling for the complete obliteration of Protestants. Outside of Paris, both the rebels and royalists were pillaging the countryside, destroying crops, and generally wreaking havoc. Things became so precarious for literally everyone that Condé eventually called for peace talks himself. The Peace of Longjumeau was signed on March 22 or 23, 1568. As with every other peace treaty we’ve talked about, no one liked it. And I know you’re not surprised because it did not give either side what they wanted. Condé disbanded his army but Charles IX did not, and in the months that followed fighting continued on much the same as it had before, if not actually worse. There are some horrific descriptions of torture that occurred in the direct aftermath of Longjumeau in Frieda’s book. I’m not going to repeat them because they make me sick to my stomach, so just know that that’s how bad they are. By some counts, more Huguenot Protestants were killed during this peace than during either of the preceding civil wars.7

Around this time, Catherine fell dangerously ill. She came down with a high fever, headaches, vomiting, and pain in her right side. After two weeks of this, she began to bleed from her nose and mouth, and discussions began of what to do should she pass. Miraculously, she survived, and by May 24th of 1568, she was back to work, albeit working from her bed. What alarmed everyone almost as much as Catherine’s illness was Charles’s, quote, “almost total paralysis without his mother beside him.”8 Though Charles was in ill health and his courtiers wouldn’t have been out of line to assume that Catherine would outlive him as she’d outlived his brother, it still wasn’t a guarantee. Catherine was 49 years old by this point and while hardy, she wasn’t in the best health either. She had gotten quite obese by this point, and often ate until she threw up. She was active though, which I’m sure helped, but yeah, people were nervous looking at the somewhat sickly Valois bunch.

Moreover, throughout France, there was kind of a sense of unraveling. People felt like the very social fabric of the country was disintegrating, and to some extent, they were laying this at the door of Catherine de Medici. It was popular to claim that she had imported all of these murderous Italian habits with her, and that was why the period of quote-unquote “peace” was so deadly. I talked more about this in the bonus episode on Italian poisoners, which you can check out on the Unruly Figures substack. Nevertheless, it was hard to deny that, quote, “what had begun as a religious struggle was turning into an anarchic, depraved free-for-all.”9

At this point, Catherine wanted this struggle over. She sent assassins after Condé, telling them to bring her his “valuable head.”10 Huguenot leaders, tipped off about this, fled France and likened their flight to Moses leading his people from tyranny and slavery in Egypt. They spread the message in propaganda, drawing people to their side. It seems like this comparison was a last straw for Catherine–soon after she wrote that her sole aim had become to, quote, “run them to earth, defeat them and destroy them.”11 She opened the third War of Religion with the Declaration of Saint-Maur, which banned the practice of any religion in France except Catholicism.

Her harder line was probably driven in part by Charles IX’s turn toward terrible health. In summer 1568, he had gone to bed with terrible fevers and was growing progressively weaker. They didn’t know it at the time, but he was in the final stages of tuberculosis, and his illness would only keep getting worse. He recovered long enough to lead a traditional procession through Paris as the third war opened; he led people to Saint-Denis where he symbolically placed his crown and scepter under Divine protection until the war was won.12 Nevertheless, the instability of the dynasty must have been clear to her–Charles didn’t have an heir except his brother, who was fighting the war, and she was quickly running out of Valois boys.

In October, Catherine’s daughter Elisabeth, Queen of Spain, died in childbirth. She was devastated by this death, but reappeared before the ruling council just a few hours after receiving the news. It seems she worried that her enemies would see this as a moment of weakness that they could use for their own advantage; she stood resolute to protect the dynasty. She also immediately suggested that Marguerite be sent to Spain to marry her sister’s widow, King Philip. This was at least in part to try to keep Spain as–well, if not an ally, at least not an enemy. Philip quickly made it clear that a marriage with Marguerite was out of the question; not only because she was his dead wife’s sister, but also because he didn’t like how Catherine had been handling the religious discontent in France so far. Even though she’d basically come to his side and seemingly agreed that destroying the Protestants was the only option, he was still offended that it had taken her so long.

Once again, France found itself cash poor and in need of financial help to mount another war. Catherine resorted to selling some of the jewelry she had brought to France with her when she’d married Henry. Cosimo de Medici, Duke of Florence, was eager to repatriate the jewels, but he still haggled with her over them. She used some of this money to pay the Protestant Prince of Orange, who had arrived in France with a large military force to aid the Huguenots, to leave again. Which he did.

Henri began his first battle at Jarnac on March 16, 1569. Catherine was in bed with a fever again during this, and Marguerite wrote in her memoirs that it seemed like Catherine could quote, “see the battle of Jarnac” in her sleep.13 This is not the first time that Catherine had prophetic dreams–she’d dreamt of her husband’s death the night before it happened. This time, she cried out in her sleep, quote, “See how they run! My son is victorious. Ah! My God! Pick up my son he is on the ground! Look, look, among the troops, the Prince de Condé is dead!”14 Sure enough, the next day the king was told that his troops had won at Jarnac, and that Condé was dead.

Apparently, Condé had injured his leg the night before the battle. Nevertheless, he’d mounted up anyway and somehow broke his leg in the process of mounting his horse so badly that the bone of his leg was poking out of his boots. Which seems gruesome and also like something a person would pass out from? Nevertheless, he led a cavalry charge that was ultimately “hopeless;” apparently before riding out he said, “To face danger for Christ is a blessing… Brave and noble Frenchmen, this is the moment we have waited for.”15

Now, April 1569 is one of those tentpole moments for Catherine’s terrible reputation as a poisoner and murderer. On the 7th of that month, the Spanish ambassador met with the Queen Mother. He suggested that “the time had come for la sonoria,” which according to him, meant the assassination of the chief living rebels, Coligny, his brother d’Andelot, and François IIII de La Rochefoucauld.16 I know I haven’t mentioned them much but that’s because they were kind of in the background of these wars until this moment. So just suffice to say that with Condé dead, these three were considered the leader of the Huguenots.

Catherine apparently pretty much agreed, saying she had even considered assassinating them when they were all in Paris several years earlier, and would have done had she known how much grief they’d cause her with these wars. I think we can all pretty readily agree that someone else would have stepped in to fill these leadership boots and these wars were the products of tides greater than these three and Condé. But that was apparently how Catherine was feeling. She put out an order for each of them to be brought to her, dead or alive, and attached significant sums of money to each person.

A month later, d’Andelot was dead. His brother Coligny and Rochefoucauld took ill at the same time, leading everyone to believe that the three had been poisoned. They survived however, though Coligny only barely. The Cardinal de Châtillon, Coligny’s surviving brother, fled to England, where he wrote letters accusing Catherine of poisoning the three. He claimed that a post-mortem had confirmed this, though again–if you listened to the bonus episode on poisoners, you know that post-mortems were in their infancy and not super accurate because Renaissance doctors just didn’t have the medical tools or knowledge to actually accurately test for poison after death.

Additionally, Châtillon claimed that a young Florentine was bragging about quote, “making the Admiral and his brother drink form the same cup” and petitioning Charles IX for a reward for killing d’Andelot.17 Meanwhile, the Spanish ambassador reported to King Philp in Spain that Catherine had been approached earlier in the year by an Italian sorcerer who worked in a, quote, “squalid place known as the ‘Vallée de Misère’ on the Quai de Mégisserie in Paris.”18 She hired him to quote “cast lethal spells on Condé, Coligny and d’Andelot that would kill them.”19 Apparently this sorcerer had cast bronze effigies of the three men and adjusted the screws on them much like a doll you’d stick pins into. Supposedly when they died, Condé and later d’Andelot’s bodies had, quote, “strange marks upon them that did not seem to relate to their overt cause of death.”20

It’s unclear whether any of this is true, and I have my doubts about bronze life-size dolls used to kill Condé and d’Andelot. Coligny remained alive though, and in July or August of 1569, Dominique d’Albe was arrested and hanged for conspiracy to assassinate Coligny–he had been found with a sachet of poison and was claiming to be a servant of Coligny’s, despite carrying evidence with him that he was an agent of Henri, Duke of Anjou. He was hung in September 1569.

The next month, the royalist army began a siege of Saint-Jean-d’Angély. Continuing her previous pattern, Catherine opened peace talks during the siege. In addition to the low royal coffers, she also had to deal with discord within the royalty camp because the, quote, “latent rivalry between the King and Anjou simmered barely under control.”21

Jeanne, Queen of Navarre, was a formidable force in these peace talks, insisting that any treaty they agreed to much include absolute freedom of worship. Also included in the peace talks was a marriage between Catherine’s daughter Marguerite and Jeanne’s son Henri of Navarre. The marriage would unite the two branches of the royal family, unite the kingdoms of Navarre and France, and–hopefully–bring some peace to the kingdom. They were modeling it on the marriage of Elizabeth of York to Henry Tudor, which had ended the famous War of the Roses, which was also a civil war.

Unfortunately, seventeen-year-old Marguerite had fallen in love with a different Henri–Henri of Guise. You might remember the Guise family for the prominent role they played in Francis’s reign in part two of this story. Anjou was told of their affair, and he passed the news on to Charles and Catherine. Rumors flew that the couple had slept together and Charles and Catheirne lost it. This is one of the truly despicable Catherine’s reign and if physical assault bothers you, skip ahead about thirty seconds.

Upon learning of this affair, Catherine summoned Marguerite to her rooms. Apparently, she showed up in a nightdress, which seems unlikely to me, but what is definitely true is that Catherine and Charles beat the crap out of her as punishment for this. They pulled out chunks of her hair and beat her until she was concussed. Then they left her there alone. Eventually Catherine realized that a princess of the court couldn’t be seen this way, and gave Marguerite new clothing and tried to fix her hair and face so the damage didn’t look so bad.

From then on, Marguerite’s brothers Charles and Henri treated her, quote, “like lovers scorned.”22 This flirtation, innocent or consummated, had seemingly destroyed the quote, “unnaturally deep bond” Henri had felt toward her, but it caused trouble for her for the rest of her life.23

Henri of Guise fled, and when rumor of his affair got out, the whole Guise family fled court. Whether or not the two really had sex, it would have looked very bad for the family even for the rumor to go around–they would have been held responsible for the undoing of her reputation, so they retreated to avoid scandal. The silver lining of this is that the ultra Catholic warmonger and Guise family member, the Cardinal of Lorraine, was then not present for the ongoing peace talks with the Huguenots, so they were able to actually come to an agreement.

As Jeanne wanted, the new Treaty of Saint-German allowed freedom of worship, though with restrictions around locations. As usual, no one was happy about it. And there’s evidence to suggest that Catherine even didn’t really feel much confidence in it. But she saw the treaty as a chance to heal wounds and bring the kingdom more fully back under Valois control.

The country at peace, Catherine turned her attention to negotiating marriages for her three eldest children: Charles IX, Henri, Duke of Anjou, and Marguerite. Specifically, a possible marriage between Henri and Elizabeth I of England was proposed. Catherine was actually very excited about this, despite their huge age difference and religious differences. But Henri put his foot down–as a Catholic, he was in the camp that believed that Elizabeth was actually illegitimate because her father had not been free to marry Anne Boleyn. He refused to marry an illegitimate heretic, regardless of her station, and he was even less interested in marrying a woman who had, quote, “dallied with such a number of admirers.”24 He openly called Elizabeth a “public whore,” a comment which got back to her.25

Seeing Henri wouldn’t budge, Catherine then suggested that Elizabeth marry her younger son, François, Duke d’Alençon, and Elizabeth went right along with it. She wasn’t actually looking for a husband, she was just trying to make Spain nervous by suggesting she might ally with France.

Meanwhile, in November 1570, Charles IX’s bride, Elisabeth of Austria, arrived. Charles seemed struck by her beauty and Catherine by her sweet innocence–between the two of them they carefully protected Elisabeth from the “wanton ways of the Court.”26 The morning after the wedding, the bride was “completely smitten with her husband and from that day forward devoted herself to his happiness.”27 I wonder if to some extent she reminded Catherine of an innocent version of herself–what she might have been like had she not endured such hardship in Florence before coming to France.

Little did she or Catherine know, however, that Charles had fallen in love with a bourgeois Protestant named Marie Touchet. He entrusted Marie’s care to his sister Marguerite, convincing her to make Marie a lady-in-waiting so that he could see her at court. When Catherine did find out, she actually really approved of Marie–she, quote, “harboured no aspirations to control Charles or detach him from [Catherine].”28 Marie ended up being a good influence on Charles, calming his tempers, and eventually bearing him a son. The baby grew up to be handsome and sweet, and was later given the title Duke of Angoulême.

Like Catherine before her, Elisabeth learned to tolerate Marie. Charles reportedly genuinely loved both of them, going out of his way to, quote, “kindly and gently” teach Elisabeth how to speak French, as well as French manners.29 Henri, though, unable to resist teasing his older brother, flirted shamelessly with Elisabeth in front of Charles. It seems like she was maybe amused by this, but never strayed from Charles.

Now married and about twenty-one-years-old, Charles was showing actual ambition for the first time. He began to make, quote, “increasingly serious attempts to free himself from his mother’s domination in matters of state.”30 Through a convoluted series of diplomatic maneuvering, Charles agreed to an alliance with Cosimo de Medici, who had been created the Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1569. Their alliance was against Spain, with a goal of taking territory in the Spanish-controlled Netherlands, and therefore sort of in favor of the Protestants. Catherine stood back and watched this with frustration. She knew that a war with Spain would be disastrous, and she did all she could behind the scenes to prevent it.

Thankfully, Cosimo de Medici pulled out. He decided he wanted to go to war with the Ottomans, a war the French would never agree to because they had a long and prosperous happy history with the Ottoman Empire. They were not going to join a holy war, and Cosimo withdrew his support of the French designs on The Netherlands as a result.

Around the same time, Catherine and Charles invited Coligny to court to try to make nice with the unkillable Protestant leader. He spent five weeks in their company, and he and Charles actually became quite close. Under his influence, terms of the treaty that had been ignored in Paris, were finally enforced, including the dismantling of visual monuments to either side of the civil war. Toward the end of his visit, he and Catherine made a deal: If he would help her get Marguerite married to Henri of Navarre, then she would help him with freeing The Netherlands from Spanish rule.

Jeanne, Queen of Navarre, wasn’t a fan of this proposed marriage, but found herself unable to really get out of it. She knew that she only retained her throne–and Henri only retained his status as Prince of the Blood–because Catherine had interceded on her behalf with the Pope. Without Catherine’s support, Jeanne’s position as Queen could have been much more perilous. Nevertheless, Catherine wrote to Jeanne to reassure her that she would be safe. We get a little glimpse of Catherine’s contemporary reputation in Jeanne’s reply. She wrote, “Forgive me if I feel like smiling, when I read your letters. You allay fears that I have never felt. I do not suppose, as the saying is, that you eat little children.”31 Woof.

They met in March 1572 to begin negotiations. Marguerite met with Jeanne, impressing the Queen. She wrote to Henri, “Madame Marguerite showed me all possible honour and hospitality and told me frankly how much she liked you.”32 Henri’s little sister was there as well and added a postscript praising Marguerite’s beauty, which had by then already become the stuff of legend. In addition to flawless skin, high cheekbones, and full lips, she also danced well, had a great sense of style, and carried herself regally. Despite her courtesy, however, Marguerite was not excited about the marriage–she saw Henri as provincial, something of a country bumpkin. But it would get her away from her mother and her brothers, so she went along with it.

The marriage was agreed to in April, the date set for August. Jeanne’s health was rapidly failing, however, and she died on June 9, 1572, before her son had arrived in Paris for the wedding. Years later, the rumor would go around that the Queen Mother had killed Jeanne with a pair of gloves tainted with poison, made by her perfumer Maître René. In addition to being faintly ridiculous–poisoned gloves? Okay–Catherine didn’t stand to gain anything from killing the Queen of Navarre. The marriage contract was signed, and that’s all she wanted from her. Her death was a symbolic loss to the Huguenots, but they still had Henri and Coligny.

In spring 1572, a new development in Europe appeared: the King of Poland, Sigismund-August II, was practically on his deathbed. He had no legitimate heir, so the throne of Poland would fall vacant when he died, and would be filled by election. Catherine saw this as the perfect opportunity for Henri, Duke of Anjou. Charles’s health had been good for a while, and now that he was happily married, there was no reason to believe he wouldn’t soon have an heir. This was a chance for Henri, Catherine’s favorite, to have a throne of his own. She began the diplomatic work to put Henri in the minds of the Poles, so when the time came he would be the best candidate.

However, even Catherine had started to become troubled by Henri’s lack of interest in women. There had been exceptions–his sister Marguerite is one example, unfortunately–but Catherine decided that she needed to, quote, “instill simple male lust into her son.”33 She began organizing, quote, “bacchanalian feasts where, it was said, the serving girls were both beautiful and naked.”34 However, “the only noticeable effect upon him seems to have been complete indifference, if not intense boredom.”35

Instead, Henri’s group of good-looking young noblemen, known as his mignons, grew exponentially. They were not well-liked, and contemporary accounts called them Ganymedes, noted that their lack of chastity, and mocked their effeminate dress. One, in particular, said, quote, "they wear their hair long, curled and recurled by artifice, with little bonnets of velvet on top of it like whores in the brothels.”36 Part of the issue people had with Henri’s mignons was that they weren’t drawn from high-ranking noble families. They were kind of the equivalent of a second string. This might have been okay had Henri’s brother Francis survived and had sons and Henri was just one in a long line of potential heirs to the throne. But with Henri being the heir to the French, his mixing with these lesser nobles made people nervous. They felt that he had drawn them up too high, straining the fabric of court relations.37

Now, one mignon in particular deserves to be noted, largely because his death is attributed to Catherine. His name was Philibert Le Vayer, Sieur de Lignerolles, and he had close Spanish relationships. He encouraged a side of the duke that many rarely saw–his religious fanaticism. He encouraged Henri to pursue really extreme devotional practices like fasting, pilgrimages, and self-flagellation that really damaged Henri’s health. He completely 180’d, becoming extremely devout after years of outright hedonism. Catherine became extremely concerned for his health, and was heard to say, quote, “I would prefer to see him become a Huguenot than to see him endanger his life in this way.”38 Pretty soon, Philibert was found murdered in an alleyway near the Louvre, and no one even bothered to investigate. They just assumed Catherine had ordered that he be killed to save Henri’s health. Which seems unfair to me–Paris wasn’t the safest place in the world at this time, and people were pretty upset about the mignons anyway. It seems at least plausible to me that someone else had reason to kill Philibert.

Nevertheless, after his death, Henri seemed to come out of a spell. He went right back to his old debaucherous ways, but this religious episode would come back. He would go through periods of fanaticism for the rest of his life, which some historians have kind of likened to a see-saw of hedonism and guilt. They see it as part of a continuum of his sexual attraction, where he gave in to homoerotic impulses then felt guilty and turned to religion, only to fall back to those impulses. Henri probably would have been taught that sex with men was sinful, and this argument always seems to kind of implicitly agree with that. We had earlier stories of Henri being attracted to Protestantism as a child though, which makes me think that his hyper-religious periods were not necessarily driven by guilt over his attraction to men. I think he just went through phases. A lot of Catherine’s children also seem to have experienced periods of madness, for lack of a better term, and then periods when they were themselves, and this kind of seems to me like a version of that. Not to say that religious belief is madness, but that the extent to which Henri would go–the self-flagellation, the fasting, the pilgrimages on his knees–were so at odds with his usual personality, that it seems like there’s more happening here than just renewed religious feeling.

In the background, Charles almost started an international war by supporting a Huguenot invasion into the Spanish Netherlands. Everyone was mad about this, especially because the Huguenots were soundly defeated, and Catherine was in such a fit over it that she actually asked for permission to leave court. She quote, “wished to return to her birthplace of Florence. There would spend the remainder of her days…rather than stay and watch her tireless work for the preservation of the monarchy go to ruin.”39

And maybe if she had gone to Florence, her reputation wouldn’t be so stained. Because if she had, she wouldn’t have been present in Paris for the disastrous bloodbath that took place in mid-August 1572, better known as the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre.

After the chaos of the attack on the Netherlands, Catherine and Henri, who was still nominally in charge of the military, decided that Coligny had to be killed. They didn’t tell Charles this, since he had grown so close to Coligny that he had allowed him to drag Charles into the whole international incident with Spain.

Now, remember how I talked about the marriage of Henri of Navarre and Marguerite? That went forward as planned at the Louvre on August 18th. In the days and weeks leading up to it, Huguenots streamed into Paris, eager to see their big symbolic prince married. The first part of the ceremony began on a platform outside. As a Protestant, Navarre had refused to enter the church for Mass, so the wedding was split into phases, with Marguerite attending the wedding Mass with her brother Henri Duke of Anjou as a proxy for the new King of Navarre.

After the wedding were four days of feasting and spectacles, which were, quote, “surprisingly good-natured considering the tension that had built up just before the wedding.”40 Catherine scheduled her assassination of Coligny for the day after the end of the festivities, on the 22nd. People were getting antsy and suspicious though, with Huguenot officers warning Coligny that something was amiss, though they had no clear idea what was actually going to happen.

That morning, Coligny rose for a meeting with the King then returned to his hotel around eleven am. The assassin that Catherine had hired, Maurevert, was hiding behind a window on Coligny’s walk to the hotel. In a scene from a movie, Coligny happened to bend down to adjust his shoe just as Maurevert shot, meaning that Coligny was severely injured but not dead.

When everyone in the Louvre heard the news, probably not long after the shot, two things happened: Catherine holed up with her son Henri, while Charles immediately began to try to smooth things over with the Huguenots. Unaware his own mother had ordered the hit, he, quote, “promised a full investigation into the crime…forbade the citizens of Paris to take up arms, and ordered that the area around the Admiral be cleared of Catholics so that he would be surrounded only by his own men.”41

Soon after, Charles led a procession from the Louvre to Coligny’s bedside, crying and swearing to Coligny quote, “I will give up my own salvation if I do not avenge this crime against you.” In the background, Catherine and Henri agreed, crying and playing at outrage as well. Once they were back in the Louvre and alone, Henri and Catherine agreed that they needed to “finish the Admiral by whatever means” they had.42

Meanwhile, the populace was growing restless. The Huguenots, understandably riled up by this attack on Coligny, grew threatening and bullish in the streets. They had arrived in Paris more or less on a layover on their way to The Netherlands to continue their attacks on Spanish forces, so they were heavily armed. The Parisians, who had not forgotten the desperate siege in 1657, were very threatened by the site of these armed Protestants, and they began arming themselves as well. Authorities began making rounds of the inns and boarding houses where Huguenots were staying, compiling lists of Protestant names. Obviously, this only served to raise their anxieties further.

In the Louvre, Catherine and her inner circle, which included the Guise family, began to get nervous that the Huguenots might strike if they didn’t strike first. Their plans morphed: Rather than just kill Coligny, they were going to try to take out his senior Huguenot lieutenants with him.

On August 23rd, Catherine had Charles informed of the truth behind the plot. Once Charles absorbed the truth of it, he had no idea how to proceed–on the one hand, he had come to love Coligny as an uncle, but he was soon faced was his mother insisting that she had done this for the good of the realm. She argued forcefully in favor of continuing with the plan she had devised with the Guises: Assassinating specific people in high command of the Huguenot cause.

After hours of this, the quote, “young, ill, and unstable King is said to have uttered the immortal cry for which he is principally remembered: ‘Then kill them all! Kill them all!’”43 Now, again, Catherine had drawn up a specific list of people who considered enemy combatants. Despite the fact that the realm was technically in a period of peace, the writing was on the wall, a fourth War was coming, and she was afraid it was about to explode while they were all in Paris together. Granted, this list has not been unearthed, but that’s hardly surprising–Catherine would have destroyed it, given how sensitive it was.44

In fact, Catherine was so committed to secrecy in this, she didn’t even warn Marguerite what was going to happen, though Marguerite would have been in danger. Due to her recent marriage to Henri of Navarre, she was staying in the Protestant apartments at the Louvre, where much of the killing would be happening. It should be noted that the Protestant King of Navarre was not on Catherine’s list; she was not about to assassinate a king ordained by God, as she would have seen it.

Once Charles approved, they moved quickly. They claimed that Huguenot forces were marching on Paris, giving the order for the gates to the city to be locked. Weapons were issued to Catholic bourgeoisie for their own self-protection, and cannons were placed in front of the Hôtel de Ville, the Paris city hall. The King’s royal bodyguards and some specific troops of the Guises were going to carry out the actual killing.

Coligny was killed first, his murder directly overseen by the Duke of Guise. Most of the Huguenots were asleep as the killing started just after four am. They were dragged from bed, unable to fight back. By five am, most of the people Charles and Catherine had ordered assassinated were all dead.

Then things got beyond their orders. She had wanted people she saw as enemy combatants killed. It’s distasteful, but I want to clearly say that what happened next was not her plan.

Now, as the day dawned and it became clear that an attack on the Hugeunots had begun in the night, the once-strategic assassination was overrun by mobs and became a massacre. Thousands of Protestants had come to Paris for a royal wedding, and were attacked in their bed, same as the soldiers. The murders were indiscriminate–men, women, and children were murdered by normal Parisians and military troops alike. The bodies were stripped for loot and dragged through the streets to be humiliated.

Frieda notes grimly that,

as the frenzied slaughter broadened in scope, old scores could be conveniently settled cloaked by the bloody, dusty chaos…a number of bourgeois Catholic Parisians had suffered the same fate as the Protestants; many financial debts were wiped clean with the death of creditors and moneylenders that night. Here was an opportunity to rob a neighbor, kill a personal enemy, or perhaps even rid oneself of a nagging wife without risk of discovery, amidst the insane, seemingly unstoppable carnage.45

Priests and preachers actually encouraged the bloodshed, preaching into the streets that this ordained by God, I guess as a sort of holy war. Horrified by what was happening, Charles gave orders that everyone was to put down their weapons, but it wasn’t heeded. The violence continued for three days, Paris ruled by a mob while the royal family tried to get it to stop. Instead, news and violence spread outward from Paris. The “orgies of killing” continued into October.46 It’s impossible to say exactly how many people were killed, but estimates of the full death toll range from 20,000 to 30,000 people in the full Kingdom.47 Around 2,000 to 3,000 had died in Paris alone–despite the fact that only a little over 1000 Huguenots were known to be in the city. At least 1000 of the dead were Catholics, possibly killed as a general reprisal of “the ‘haves’ killed by the ‘have-nots’.”48

After all that, a few senior Huguenots had escaped Paris, carrying with them the seeds for the fourth War of Religion. After the bloodletting calmed, Charles had held a special Lit de Justice where he took responsibility for the initial killings, carefully listing the outrages and crimes committed by the Huguenot leaders. He tried to say that it had simply gotten out of control, that mobs had ruled and that hadn’t been his intention, but people really believed that the, quote, “royal marriage had been a devious trap set by the Machiavellian Queen Mother, perhaps with the backing of Spain, to capture and exterminate” French Protestants.49

Catherine saw now how bad of an idea this had been from the start. The Protestants had previously trusted her, now they believed the preachers and pamphleteers who claimed that “the ultimate responsibility for the premeditated and terrible massacre lay at her door.”50 Even though that had emphatically not been her plan, it’s a part of her reputation that she never lived down. Moreover, once Charles had claimed responsibility for ordering the assassination of the leaders of the Huguenot party, quote, “Protestants knew they could no longer offer him allegiance.”51

To make matters worse for Catherine and Charles, the Pope was thrilled. He had a special medal struck to commemorate the massacre, and the French ambassador to Rome published a pamphlet telling the tale and titling it The Stratagem of Charles IX.

Despite her own regrets, Catherine didn’t seem to fully perceive how bad this made her look. The massacre became, quote, “a weapon for her enemies to mould and use against her,” a fact she didn’t grasp.52 Catherine was great at promoting the grandeur of the monarchy, but it seems like she was less adept at understanding how propaganda could be just as influential. People began to say that Catherine had been planning the massacre for years, and she so mishandled the aftermath of the crisis–and of course, the crisis itself–that she never shook these accusations from her legacy.

And of course, the massacre did nothing dampen the religious zeal of Protestants. New leader stepped up to take over the cause, and the fighting began again.

Meanwhile, Catherine was still pushing forward plans for Henri to become the King of Poland. Charles IX was encouraging as well; he saw it as a chance to be rid of the younger brother who often outshone him. She had sent Jean de Monluc, the Bishop of Valence, as a special envoy to Poland in order to campaign for Henri in the election. Of course, other monarchies were vying for the throne as well, and Henri’s role in the disastrous massacre on St. Bartholomew’s Day was amplified by rivals to discredit him.

But Monluc did it. He got Henri elected to become the next King of Poland, though his success probably has more to do with the issues voters saw in the other candidates rather than any amount of genuine excitement for Henri. This has “the least bad option” written all over it.

He had been reluctant before, and though he was initially excited to win, he became reluctant to leave. Poland was far away, with enemies like Ivan The Terrible right on its doorstep. He also felt that it wasn’t culturally as advanced as France and the rest of Western Europe. Instead saw it as a kind of exile and he was, quote, “piqued at his brother’s determination to banish him.”53

The other issue Henri perceived, that several others seemed happy to ignore, was that Charles was visibly dying at this point. His health was deteriorating quickly, and it became clear that he wasn’t going to have a son with wife. Their marriage had produced one daughter, but the French were not ready for a girl to inherit the throne directly just yet, though they had already witnessed that happening in Navarre and England. To send Henri away now, when Charles could keel over at any minute, seemed foolish in the extreme. And in fact, as the royal family began a procession to the French border to bid him farewell–a Renaissance version of dropping your kid off at college, it seems–Charles took so ill that French nobles protested Henri’s departure. He was terribly feverish and, quote, “covered not only by sweat but also by a watery blood that seemed to seep from the pores of his body.”54 And this is why you don’t want to ever get tuberculosis, the method of dying is very painful.

But Charles rallied and demanded that Henri depart for Poland. Catherine ensured the two brothers said goodbye with a proper amount of weeping, and some onlookers wondered if there wasn’t genuine sorrow–Henri, at least, must have suspected that he’d never see Charles again.55

Henri’s departure made room for a new drama, however: Catherine’s youngest son, once called Hercule but now going by Francis, Duke of Alençon, got it in his head that he wanted to be the next King of France. To be clear, Henri was still the formal heir to the throne, but Alençon wanted to throw him over to get it himself. He aligned himself with the Huguenots Navarre, Condé, and the Montmorency family to begin a campaign to take power. His supporters published a huge number of pamphlets that blamed Catherine, as a foreigner and woman, for the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew. They published more that questioned whether it was legal for Catherine to be regent under Salic Law, arguing that if the ruler must be male, then so too much the regent. Finally they claimed that history’s most brutal tyrants had all been female, a fact that is actually just a lie.

The truth is that Alençon was not really bright enough to have masterminded this all himself. He was probably of average intelligence, but through his own desire for power he made himself a very useful tool to much smarter and more dangerous people who had other conspiracies in mind–namely, war with The Netherlands and the undermining of the Valois family and Catholic domination.

They developed a plot wherein Navarre, Marguerite’s husband, and Alençon would flee court for the Netherlands on Mardi Gras, and a force of Huguenots would attack just after, probably killing Charles and Catherine in the process. At the last minute, Alençon panicked and told Catherine the whole plan. She arrested both of them and their followers, and the whole court fled the oncoming soldiers in the Château de Vincennes, a fortress that they’d be safer in.

Afraid they’d be executed when the whole plan came to light, they tried to escape again. But the people they trusted didn’t have the discretion or guile to carry off a plot like this, so rumors flew and Catherine was able to arrest fifty of Alençon’s close followers. During the investigation that followed, it was discovered that Catherine’s favorite sorcerer and specialist in the dark arts, Cosimo Ruggieri, had created “a wax doll wearing a crown, with needles piercing its heart.”56 She was devastated that a man she had trusted for so long could have betrayed her this way. It eventually came out that the doll had actually represented Marguerite, not Charles; her lover La Molle had apparently asked Ruggieri to cast a spell on her to make her fall in love with him. Honestly, to me this sounds like he was making up any lie he could to save his life and Catherine just wanted to believe it.

Navarre and Alençon were spared any serious punishment–they were put under essentially house arrest at Vincennes, which is light considering that they had been plotting to kill a King.

At the end of May 1574, it became clear that Charles’s time was up. When Catherine burst into his room on the 29th to try to give him good news, he said, “Madame, all human affairs no longer mean anything to me.”57 Realizing that he could die at any second, she quickly had a document drawn up that declared her regency once again until Henri could be recalled from Poland; he’d only arrived there in January. Charles passed away on the afternoon of May 30, 1574.

Catherine allowed herself to feel her sorrow for a few hours, but had to write to Henri to bring him back to France fairly quickly. In her letter informing him that he was officially King of France, she wrote, quote, “My only consolation is to see you here soon in good health as your kingdom needs you, for if I were to lose you, I would have myself buried alive.”58 She counseled him on how to leave Poland so as to not lose the territory they had just gained peacefully, but Henri was destined to not listen. Though the Poles didn’t particularly like Henri himself, he represented the prestige and benefits of being tied to a Continental superpower, and they were not eager to see him leave.

Henri, never particularly good at planning in advance, had not really prepared a plan for the inevitable death of Charles IX. He had seduced the Poles into believing that he was happy there, though he had so far refused to spend much time with Princess Anna de Jagellona, who he had promised to marry when he’d agreed to become the King.

Therefore, when news broke of Charles’s death in mid-June, the people in Poland were very alarmed. Henri calmly announced that he was going to let the people of Poland decide what he should do in a formal meeting in September, and meanwhile Catherine would act as regent. This wasn’t what he actually planned to do though. He made his escape on Friday June 18th, and it was a literal escape. He ran off into the night, stealing Polish gems with him on his way out–he knew they’d come in handy if he needed to bribe his way out of Poland. Through unfamiliar terrain and not speaking the language, Henri and his French courtiers basically did a runner, just barely outpacing the Tartar cavalry troop and furious subjects who had quickly begun to chase their wayward King.

Once he was safely in Vienna, Henri wrote to Catherine, “I am your son and have always obeyed you, and I resolve to devote myself more to you than ever before… France and you are worth more than Poland.”59 Considering that Catherine had told Henri to do whatever it took to keep Poland, I find it very easy to roll my eyes at this phrasing. The Polish government issued an edit telling Henri that if he didn’t return to Poland within six months, his throne would be considered forfeit and they would elect a new king. I’m not sure he even bothered to reply.

Once he’d escaped Poland’s borders though, Henri’s mad dash became a stately journey. He celebrated his new role as King of France along the way, handing out Polish and French jewels to anyone who pleased him. He had inherited Catherine’s extravagant and generous habits, clearly. Catherine, meanwhile, sent him, quote, “increasingly frantic letters…urging him to return as the turbulent political situation in France worsened.”60 He didn’t really speed up. He finally arrived in Lyon on September 5, ready for his coronation.

Catherine was fifty-five when her favorite son ascended the throne. Considered well into her old age by the standards of the day, she nonetheless retained a capacity for hard work. Leonie Frieda notes that “she thrived on the challenges she faced.”61 She was often known to work late into the night after a banquet, and survived on very little sleep more often than not. Though she was excited for her favorite son’s triumph, she was also anxious about it–she was, quote, “long used to the habit of power,” and had no idea how much she’d be able to exercise with him on the throne.62

Unlike his brothers, Henri came to the throne as an adult. He was intelligent, but distracted by his mignons, as well as a new obsessive love for the new Prince of Condé’s wife, Marie of Cleves. Marie and Henry, Prince of Condé had been separated ever since his involvement with Alençon’s treacherous plot, and one of Henri’s first missions as King of France was to try to secure a divorce for the two so he could marry Marie himself. Catherine was horrified by this and advised Henry against it. In the end, Marie died before Henri’s plans could really take shape. He ended up marrying the sweet and gentle Louise of Lorraine on February 14, 1575. Not for nothing, she looked a lot like Marie. Henry doted on her though, often insisting on dressing her and styling her hair himself. The couple had no children.

Catherine began carefully and tactfully giving Henri suggestions on how to start his reign. She encouraged him to have a small council that he could trust to help his rule. She also encouraged him to ignore the gossips who called him, quote, “King of the Island of Hermaphrodites,” a derogatory reference to his love for sumptuous clothing and jewelry.63 She got him to focus on work, and he really did–the days of councils and secretaries handling everything were finally gone; Henri genuinely got involved, even revoking Catherine’s right to open diplomatic mail without him seeing everything first.

The pamphlets that Alençon had had authored had been like a dam breaking. A flood of similar pamphlets attacking the regime in general and Catherine in particular “deluged” France.64 The most influential was The Marvelous Discourse of the life, Actions and Deportments of Catherine de Medici, Queen Mother. Written by someone with access to Court life, it blended fact with fiction to accuse her of, quote,

every lurid and horrible crime imaginable. She had not only killed every person whose death had been convenient to her, orchestrated the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew, seduced her sons into lives of fecklessness and debauchery so that she might usurp their rights, but her whole life was also so motivated by greed, hatred and a lust for power that no crime was too vicious for her provided she kept her position as the de facto ruler of France.65

Catherine apparently found the whole thing amusing. She believed that the charges were clearly so exaggerated that she, quote,

encouraged her ladies to read it to her aloud. The only pity, she commented, was ‘that the author had not previously applied to me for information, as by his own statement ‘it was impossible to fathom the depths of her Florentine deceit’... and he evidently knew nothing of the events he pretended to discuss. Besides, she laughed, 'he had left so much out!'66

Which, I mean, I don’t know that this was the best response. Had she come down hard, people might have thought she had something to hide, but saying that he hadn’t even figured out the most lurid stuff she’d done seems like it invites the same amount of speculation in. Her time as Queen Mother probably would have been tainted enough by the massacre and her interest in magic and astrology, but this little novel did a lot of damage to her legacy too because people couldn’t tell where fact ended and fiction began.

In December 1574, Catherine’s long-time enemy and occasional ally, Charles of Guise, Cardinal of Lorraine, died at forty-nine. His death shocked her, and for the first time ever she couldn’t think of anything to say to mark the occasion. A few nights later, she believed she saw the cardinal standing before her at dinner and, quote, “dropping her glass she uttered a cry.”67 Like Macbeth, she seemed to be haunted by his death, dreaming of his ghost. As she entered in 1575, she had to have realized that she had outlived many of the people who had made her early life difficult. And yet the problems they represented remained.

Meanwhile, in early January, a group called the Politiques, led temporarily by Prince Henry of Condé, declared themselves a separate state in southern and south-central France. The Politiques were made up of moderates from both the Catholic and Protestant camps, who advocated for a strong central monarchy that would allow religious freedom. France was too poor to deal with this, and Catherine was bankrupting the royal treasury to achieve his coronation in wedding in February. In fact, the country’s financial troubles were a main inspiration for this parallel state. The country in general was bankrupt, a fact the royal family could see only too clearly in the emaciated faces of the peasants they passed as they traveled from Avignon to Rheims for his coronation. Catherine urged Henri to deal with this, but whatever burst of work ethic he’d felt when he arrived back in France had burned itself out. He left his mother to do the work and, quote, “could no longer be bothered to attend the council meetings but engaged in frivolities with his mignons instead.”68 This was obvious to his subjects, and someone graffitied a wall near the Louvre with the phrase, quote, “Henri de Valois, King of Poland and France by the grace of God and his mother, concierge of the Louvre, hairdresser-in-ordinary to his wife.”69 What a burn, right?

To deal with Alençon and Navarre, who were tacitly supporting the Politiques who had created the breakaway state, even as they remained at court, Henri decided to do some underhanded intrigue instead of deal with them directly. Enlisting the help of Catherine’s Flying Squadron, he ordered the beautiful Charlotte de Beaunne, who was already a mistress of Navarre’s, to make him compete with Alençon for her attention. She led them both on, causing “great friction” between them until they “became extremely jealous of each other…to such a point that they forgot their ambitions, their duties and their plans and thought of nothing but chasing after this woman.”70 I both can’t believe this worked and also am completely unsurprised–of course it worked. Soon after, a delegation of Politiques came to Paris to present their terms for peace to Henri. He rejected all their demands and fighting broke out again, destabilizing the country again.

Soon after, Alençon escaped Paris. Henri ordered his nobles to give chase and bring him back dead or alive, but no one was willing to go against the apparent heir. On the throne for less than a year, Henri had made himself extremely unpopular already.

Catherine realized she’d have to deal with Alençon herself. She traveled to Chambord in late-September. They spent a few days negotiating, and Catherine urged Henri to accept Alençon’s terms. She also, however, urged him to prepare for war, seeing already that Alençon did not intend to really honor the peace. They signed a six-month truce, in November, but it didn’t hold long past January 1576. Henri blamed Catherine’s for the failure of the treaty, though neither side had helped up their responsibilities.

Fighting lasted until May 1576, when they signed the Peace of Beaulieu, which was a triumph for French Protestantism. Victims of the Saint Bartholomew Massacre were rehabilitated from theri reputation as heretics, and pensions were paid to widow and children of the victims. The Protestants were granted control of 80 towns where they could practice their religion freely. Henri was devastated by the terms of the treaty and felt as though Catherine’s advice to prepare for war had been too little and too devastating. Henri never really trusted Catherine again.

However, in September of 1577, a mission for her came up, and it quickly became clear that she was the only person Henri trusted to complete it. After the end of the Sixth War of Religion–though realistically, the times of peace were so violent themselves that it’s hard to distinguish where each war ended and began–there was a real need to have representatives of the crown tour France. Much like the tour Catherine had embarked on at the beginning of Charles’s reign, in 1564-66, this would take the 59-year-old woman all around France, mediating disputes and showing off the power and glory of the French monarchy. However, Henri would not be joining her–he stayed behind while she took great personal risk by traveling through what was effectively enemy territory. She endured not only open hostility in some places, but plague, social strife, and bandits. Her temper remained, quote, “resolutely breeze in the face of the hardship and hostility she often encountered.”71 Along the way, Catherine, quote, “managed not only to find solutions…to the deep-seated divisions France faced, but also gained the respect and grudging affecting of her former opponents for her absolute commitment to maintaining the peace.72

The most dangerous part of her experience was at Montpellier, the Huguenot stronghold on the southwest coast of France. When she entered the city on May 29, 1579, she, quote, “drove with cool composure between two rows of hostile Protestant arquebusiers, her carriage even touching their muzzles where the men stood menacingly, pressing close.”73 Despite the clear and present danger there, Catherine pressed on and was rewarded for it. As Frieda wrote, “her plush and dauntlessness bought her the respect of the townspeople. By the time she had completed her work there and started on the next part of her journey, she left them courteous and almost dutiful.”74

Catherine returned safely to Paris in October 1579. She’d been away for over two years. In that time, Henri had almost died at least once, but was recovered and trusting of his mother again. Many other government people, including the Venetian ambassador, finally recognized Catherine as an incredibly intelligent and successful stateswoman, whose work seemed poised to ensure peace in the country for a while longer. This was not to be though–another short war broke out in 1580 and was quickly brought to a peace in November of that year.

Despite her travels, Catherine also found time to start negotiating a marriage for her youngest son, Alençon. Henri and his wife seemed unable to produce an heir, so Catherine saw that it came down to Alençon to ensure the continuity of the Valois dynasty. However, the most illustrious of brides suggested to him was also probably the least fertile: Elizabeth I of England. I’m not trying to insult her, it’s just that she was 45-years-old at this point. With what little understanding of prenatal care people had in the Renaissance, plus her own drinking and use of poisonous makeup, it would have been a miracle if Elizabeth conceived a child at that age.

But they went through the pretenses anyway. Alençon even traveled to England in August 1579, staying for two weeks in a quote, “delightful flirtation.”75 Elizabeth called Alençon “her frog” and seemed at least fond of him when he left, but the wedding didn’t move forward.76 Two years later, Alençon went to England again and the two layed a diplomatic game of escalating proposals, neither one really wanting to marry the other but both even less willing to lose face in front of their respective courts. But Alençon was still obsessed with the question of the taking land in the Spanish Netherlands, and so Elizabeth made it a condition of their marriage that she couldn’t give him money or men for that venture, plus France had to agree to come to England’s aid if they were attacked by Spain. On the other hand, if he didn’t want to get married, Elizabeth could give him 60,000 pounds for his mission. Catherine was sick at this suggestion because, as we’ll see in a moment, she had France’s military tied up somewhere else. But Alençon agreed, saying that he was so in love with Elizabeth that he would basically give up everything. Horrified, Elizabeth had to give him increasing amounts of money and military power to get him to go away; he eventually left with a militia and entered Antwerp, where he was installed as the Duke of Brabant in February 1582. He got everything he wanted, but he didn’t enjoy it for long.

In 1580, several catastrophes fell upon France. Three epidemics ravaged the country–one in February, another in June, and then the plague in July. In April, an earthquake hit Calais, but it could be felt as far away as Paris and London. Just a few days later, terrible storms flooded the capital.. Anywhere from 30,000 to 140,000 people died from these combined disasters.77 The earthquakes caused a general uproar of concern, with people swearing that it was a sign of God’s displeasure with both England and France.78 Earthquakes were seen as an astrological phenomenon as well, something that could be predicted by the movements of planets and stars.79 We can assume that Catherine consulted her favorite astrologers about what this meant, though no one seems to note it.

Starting in 1580, Catherine was consumed with thoughts of Portugal: The King there had died, leaving the throne empty. She had a tenuous familial connection to him on her mother’s side–she was a descendant of Alfonso III, who had died all the way back in 1279.80 Philip II, King of Spain, had a much stronger claim to the throne: His mother was the dead King of Portugal’s sister. He fully intended to take Portugal’s throne and unite it with Spain. For two years, the two powers fought over Portugal. In the end, Catherine lost to Spain’s superior military power.

1584, Alençon died, probably of consumption. He had caused a lot of trouble for Henri and Catherine, but she was still devastated by his loss. Her daughter Claude, who had provided Catherine some of the only happy familial memories she’d ever had, had died a few years before as well. By this point, Catherine had outlived eight of her ten children. And with only King Henri III left of her boys, it looked like the next King of France would be Henri, King of Navarre, who had married her daughter Marguerite.

Henri supported Navarre’s candidature and declared him his legal successor, though the country wasn’t really having it. He was seen as a heretic and a succession crisis quickly developed. Many advisors encouraged Navarre to simply revert back to Catholicism to end the crisis, but his kingdom was in the heart of Protestant territory–he couldn’t risk it.

So our old friends the Guises rose again, this time with Henri of Guise back to demand power from King Henri of France. The King had hated Henri of Guise ever since his flirtation with Marguerite several years before and didn’t want to see the Guises take the throne. However, he knew he needed the support of the Catholics in France. So Henri named the Cardinal de Bourbon his successor instead–a prominent Catholic who was also part of the House of Bourbon, making him a Prince of the Blood, though not as closely related to Henri as the King of Navarre.

Simultaneously, in September 1585, Pope Sixtus V issued an edict excommunicating Navarre, denying rights of succession to any Protestant Princes of the Blood. This was clearly a bid to keep the Catholics powerful in France, and to sort of support King Henri, but it enraged the French people. They resented the Pope’s audacity to encroach on their domestic issues. Like Catherine had many years before about Queen Jeanne of Navarre, many people simply ignored what the Pope had to say.

Now in her sixties, Catherine’s health was declining. Anyone else would have retired, but she seemed to view this moment as the greatest test of her life’s dedication to preserving the Valois dynasty. She made several journeys to meet Navarre, though by this point he believed she had little real political influence. And to some extent, he was right: Henri had raised up his mignons so high that they largely controlled what he was told and what was happening around him. Realistically, Navarre knew that he was going to have to fight for the French throne. He met with moderate Catholics, creating an alliance to defeat the militant Catholics that were convincing Henri to name Cardinal de Bourbon as his successor.

Back in Paris, Catherine despaired of Henri’s newest phase of religious fanaticism. Possibly believing that this succession crisis was his fault because he hadn’t yet had a son with his wife, he began walking from Paris to Chartres Cathedral, which was 88 kilometers or nearly 55 miles away. Today the walk would take 18 hours, and I don’t imagine he was wearing comfortable shoes. He did so to pray to the Virgin Mary for a son and beg God for absolution. His, quote, “desperate quest for redemption took on increasingly morbid and even necromantic tones. He began wearing death’s heads embroidered on his clothes and had a sinister oratory built, festooned with black crêpe, in which he placed bones and skulls that had been taken from a local cemetery.”81 Catherine of course, “fell into despair” over this, fearing for his health but also his sanity.82 Even the Pope told him to take a day off, reminding Henri that, quote, “as a sovereign on the brink of a full-scale war to save France for Catholicism his duties lay elsewhere.”83 When the Pope is telling you that your dedication to religious worship has gone too far, you really have to take a good hard look at your life.

Meanwhile, Catherine’s once daughter-in-law Mary, Queen of Scots, had been sentenced to death by Elizabeth I. She’d been a prisoner of the English queen for almost 19 years by this point, but it was only when Elizabeth decided to kill her that Catherine finally bestirred herself to defend the woman her son Francis had loved. She sent people to Elizabeth’s court to plead for clemency, and had Henri write a letter saying that he would take Mary’s execution as, quote, “a personal affront,” but nothing changed Elizabeth’s mind.84 Catherine wasn’t really doing this out of nostalgia though–Mary, once Queen of France and a descendant of the Catholic Guise clan and a staunch Catholic herself, was something of a symbol to French Catholics. Her losing battle against the Protestant Elizabeth was their great fear if French Protestantism was allowed to remain unchecked. Her execution would make her a martyr, and the last thing Catherine wanted was French Catholics all stirred up with nowhere to put their anger.

Sure enough, after Mary was executed on February 18, 1587, Catherine was alarmed to see French priests, quote, “denouncing it as an assault upon Catholicism by a heretical foreigner.”85 Mobs quickly grew out of control and started turning on Henri for not being able to save her–the French royal family came under attack for basically not protecting one of their own. War broke out between the Spanish, the English, and the Spanish-supported militant Catholics in France, led by the Guise family. They besieged Paris, taking Catherine as prisoner even as Henri was able to flee. I’m not going to get into every move of this military, but suffice to say the Spanish lost through a combination of good strategy by the English and bad weather in the Channel. Philip II had finally fallen from his pinnacle of power.

In September 1588, Henri sacked all of his ministers of state, most of whom had been appointed by Catherine when he’d first become King of France. He raised up other men, luckily smart ones of integrity, but ones who were virtually unknown and did not owe anything to his mother. Her days of power were effectively over. Henri called a meeting of the Estates-General and for the first time since her husband had died, Catherine had no reason to be there. She stayed home and nursed her gout and rheumatism.

On December 8, 1588, her granddaughter through her daughter Claude, Christina of Lorraine, married Ferdinand de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. Catherine had helped arrange the marriage and was delighted to be able to attend the ceremony, which was held in the Château of Blois. She held a small ball in her apartments there to celebrate. It was one of the last happy moments of her life.

On December 15, she went to bed feeling ill. She had a lung infection and was having trouble breathing. On New Year’s Eve, Catherine forced herself to get up and go to Mass in the chapel, than to visit the Cardinal de Bourbon, who had been imprisoned by Henri. The king, going quite mad, had decided that the Guise family was planning to assassinate him and had begun imprisoning them or killing them one-by-one instead, starting with the Duke of Guise a few days before. Catherine, too sick to do anything, had simply wept, asking the priests to pray for Henri.

On January 5, 1589, Catherine had become so weak that she could hardly breathe. Despite the uncountable number of times that she had by sheer willpower overcome her own physical ailments, it became clear to her that she was dying. She whispered her last testament to Henri, and took the Sacrament with a priest named Julien de Saint-Germain, Catherine de Medici passed away at 1:30 pm on the holiday the French call Le Jour des Rois–the day of Kings. She was sixty-nine years old.

Her death shocked people–she had been, quote, “an ever-present feature in their lives since her arrival in France in 1533. Few Frenchmen could remember a time without her.”86 But because of the state of unrest in the country, her family felt it wasn’t safe for her body to be buried at Saint-Denis. Everyone blamed Catherine for troubles which were usually outside her control, and they feared that her body would be dragged through the streets and dumped in the Seine–a threat that Parisian Catholics were actually making. She was embalmed and buried in an unmarked grave at Blois, where she remained for twenty-one years. It wasn’t until Anne de France, her husband’s illegitimate daughter, took the time to have the body moved to be buried along with the rest of the Valois line at Saint-Denis.

Despite blaming her for all their troubles, things in France didn’t calm down once Catherine died. Just about seven months later, her son Henri was assassinated by Jacques Clément, who claimed to be a Dominican friar but was in fact a troubled young man who, quote, “believed he could hear God’s voice in his head and that he had received instructions to from the Almighty to kill the King.”87 He stabbed the King with a knife that Henri’s men had failed to notice he carried.

Henri III, 37-years-old and king of France for 14 years, knew he was dying from the injury. He called King Henri of Navarre to his bed and made his men swear allegiance to him as the next King of France. Henri III, the second-to-last living child of Catherine’s, died on August 2nd 1589, ending the Valois line she had found so valiantly to protect. Navarre did not immediately ascend to the throne, but instead had to fight for it for nearly four years. Finally, on July 23, 1593, he just converted back to Catholicism, thereby making himself eligible for the throne again. He ascended as Henri IV. Surveying the city from the hilly neighborhood of Montmartre, he is said to have uttered, “Paris is well worth a Mass.”88

Though their relationship hadn’t always been amicable, time, quote, “softened Henri’s views on [Catherine]. Overhearing a group of courtiers blaming all the misfortunes of France upon the late Queen Mother, he is reported to have said, ‘What could the poor woman do, with five children in her arms, after the death of her husband, and with two families in France–ours and the Guise–attempting to encroach on the crown? Was she not forced to play strange parts to deceive one and other and yet, as she did, to protect her children, who reigned in succession by the wisdom of a woman so able? I wonder that she did not do worse!’”89

During her time as Queen and Queen Mother, Catherine introduced a number of modernizations that improved the lives of the French–the side-saddle and drawers, which I mentioned in part 1. She introduced decorative fans, which became a favorite of royal women, and handkerchiefs, which had been legally restricted to use by the nobility in Florence, but wasn’t so restricted in Paris, it seems. She promoted perfumes as well–bottled scent already existed but Catherine’s devotion to it popularized it. Makeup she wore sparingly, but she was always open to trying new products and tended to set the tone for the use of them among all European noblewomen–she wore rouge, and a wash of white lead to make her look pale.

Today Catherine’s memory lives on around France in several ways. Her two personal libraries, which contained a combined 8500 works–including ancient papyrus scrolls–formed the basis of today’s Bibliothèque Nationale. Many of her building projects remain standing as well, though the Tuileries Palace she built was destroyed during the Paris Commune, the gardens of the Tuilerie still remain. In the Tuileries Palace, she put on shows that are credited with bringing the earliest form of modern ballet to France, as well as the first violinists ever heard in France. She established a tradition of lavish spectacles put on by the state to assert French cultural dominance, a tradition that has obviously morphed but continues in a similar spirit in France today. Catherine is also responsible for popularizing tobacco in France, which had arrived from the quote-unquote “New World” in 1560. She didn’t enjoy smoking, but she crushed the dried leaves into a powder, and maybe snorted it? Claiming this helped her headaches? Her love for tobacco spread to the court and people called it la herbe de la reine; she unwittingly taught the French to love to smoke.

Her memory as the Black Queen or Serpent Queen of France seems unfair–while she made disastrous mistakes, the tides of violence that occurred during her lifetime were largely outside her control. She was uniquely powerful at a time of great upheaval in France, and she rode it out as best she could. Capitalizing on her intelligence and attractive voice, she repeatedly convinced brave men to work for her, and inspired loyalty where they might previously have only been loyal to their own agendas. Throughout her widowhood, Catherine, quote, “worked, rode, hunted and faced mortal danger with the courage of a man. In an age dominated by men, she asked that no quarter be given on account of her sex.”90 She was courageous and cunning and legendarily optimistic, even when it seemed at many points like all hope was lost. Arguably her fanatical devotion to her childrens’ birthright did, quote, “blur and blunt her judgment,” but there is also a sense that she was so devoted to the French throne out of gratitude for how it had raised her, a Florentine commoner, to greatness.91

I hope you enjoyed this mini-series on Catherine de Medici! If you did, please tell a friend about it. You can also let me know your thoughts by following me on Twitter and Instagram as @unrulyfigures, or joining us over on Substack. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks find this work. Thanks for listening!

📚 Bibliography

Crawford, Katherine B. “Love, Sodomy, and Scandal: Controlling the Sexual Reputation of Henry III.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 12, no. 4 (2003): 513–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3704668

Crompton, Louis. Homosexuality & Civilization. Cambridge, Mass. : Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003. http://archive.org/details/homosexualityciv00crom.

Frieda, Leonie. Catherine de Medici: Renaissance Queen of France. Harper Perennial, 2003.

Hayton, Darin. “Astrology & Earthquakes.” Darin Hayton: Historian of Science, November 10, 2021. https://dhayton.haverford.edu/blog/2021/11/10/astrology-earthquakes/.

———. “Pamphlets on the Earthquake of 1580.” Darin Hayton: Historian of Science, July 17, 2013. https://dhayton.haverford.edu/blog/2013/07/17/pamphlets-on-the-earthquake-of-1580/.

“Les Mignons.” In Wikipedia. Wikipedia, January 3, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Les_Mignons&oldid=1131314427.

Leonie Frieda, Catherine de Medici: Renaissance Queen of France. Harper Perennial, 2003.

Frieda, 203

Frieda, 204

Frieda, 204

Frieda, 204