So excited to be back for part two of the story of Catherine de Medici! I thought this story was only going to be two parts, but it’s turning into a three-part story, so

🎙️ Transcript

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m covering part two of the famous Queen Catherine de Medici’s life. This queen has had something of a mixed reputation for a few centuries now, but recent historians have been doing a bit of reclamation of Catherine, so we’re exploring some of these tensions. She’s remembered as a powerful leader and devoted mother but also as a poisoner and a central figure in the French Wars of Religion. For this story, I’ve been relying heavily on the 2003 biography of Catherine by Leonie Frieda, which I recommend checking out if you’re interested. It’s over 400 pages and goes into much more depth than I’ll be able to here.

But before we jump into Catherine’s life and how she became the most powerful woman in sixteenth-century France, I want to give a huge thank you to all the paying subscribers on Substack who make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t be possible without you! If you want to support Unruly Figures and my mission to make interesting history free, you can do that at unrulyfigures.substack.com Becoming a paying subscriber will also give you access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes posts, like my post last week with an exclusive Unruly Figures book update! When the book is released, paying subscribers will also receive a free signed copy.

One last thing–if I sound a little out of breath in this episode, and the next few, it’s because I, uh, broke a rib last week! I have not gotten into the good habit of recording in advance, so we’re all going to deal with my broken rib together. Kids, if you can avoid breaking a rib, I highly recommend that you do that because it is an extremely painful healing process.

All right, with that little disclaimer out of the way, let’s hop back into Catherine’s story.

When we left off, Catherine’s husband Henry I had just passed away at forty years old in a tragic jousting accident. Their oldest son, Francis, was known to be in poor health–in fact, it’s said that when he was saying goodbye to his father on his deathbed, the Dauphin cried out, “My God! How can I live if my father dies?” and fainted.

Here’s the thing: Being a widowed queen with a young son is a very dangerous position for a woman to be in basically any monarchy in European history. Catherine is no exception–the most powerful men in the country were men her own husband had built up through his favoritism, and those men began jockeying for power in the last days of Henry’s life.

The two main parties at play here are the Guise family and the Montmorency family. I mentioned both of them in the last episode, but basically, the Duke de Montmorency had acted as sort of a surrogate father to Henry which had gained him a lot of wealth and power, while the Guise family was powerful through their high government positions, extreme wealth, and their convenient familial relationship to the new King Francis’s wife: Mary, Queen of Scots.

Mary, young, beautiful, and intelligent, had a lot of influence with her husband, so where she led he followed. And she led him right to the Guise family. She of course had already relied a lot on her uncles for guidance, and she could also count on them to have her family’s interests at heart. Remember, at this point, Scotland was really struggling in ongoing battles with English encroachment, and Mary’s mother Marie of Guise, was holding down the fort in Scotland by herself as regent. Scotland relied heavily on France for support at this time, support Henry had withheld and provided based on his own goals and desires; Mary almost certainly saw this moment as an opportunity to send the military support she had long needed to protect her own crown, and so of course, that’s her mission at this point and the mission of her uncles. Saying that “Using her influence,” sounds very negative and I’m trying to cast this neutrally, but as Francis’s wife, she advised him from her perspective and with who she trusted, which led to the Guise family’s star really rising in the immediate aftermath of Henry’s death.

Obviously, this really annoyed Catherine, but she didn’t really have any power to fight back. As a widow and Queen Mother, her formal power diminished really quickly. The Guise family was able to easily start taking over major offices of state based on what Mary advised Francis to do. The Montmorency family was largely sidelined, in part because the Duke was so devastated by Henry’s death. He apparently, quote, “wandered the corridors, inconsolable at the prospect of losing his master, friend and comrade in arms.” I don’t want to say that he “made it easy” for them to take over, but I mean certainly the Guise brothers saw an opportunity to take power during his period of stunned grieving and they did.

Their first move was to get young King Francis, and the rest of the family, to the Louvre, where they could be ensconced with only the Guise family. This move was made partly because they wanted to keep them away from the Bourbon family: Antoine de Bourbon stood next in line for the French throne should Francis and all his younger brothers mysteriously die. Antoine was already King of Navarre at this point, and his historical reputation is not great: He is remembered as, quote, “lazy, selfish and weak-willed” so I doubt there was any real threat that he was going to send assassins after Henry’s kids in an attempt to take the French throne and unite it with his own, but obviously was a possibility that the Guise family wanted to avoid. So, arguably, this move to the Louvre from the Chateau des Tournelles, where Henry had died in the joust, was sort of to protect the kids, but it was also very much about consolidating their power.

Throughout Catherine’s time as queen, she had always known that these two families were a little too powerful. And she had been careful to never show favoritism to either, and in fact, Catherine, quote, “detested both parties in almost equal measure.” I think in shows like Reign this is the moment where someone would say that each family had their uses to Catherine, and there’s probably some truth to that–she certainly was not truly friends with either of them while Henry was alive and is not about to get cozy, but she also through her own grief was able to see the writing on the wall: The Guises were basically attempting a bloodless coup d’etat. Others have historically called it their, quote, “elopement for power” which is a very fascinating phrase.

So Catherine had to make some big breaks with tradition. Normally, French wives were supposed to stay in seclusion for forty days after the deaths of their husbands, but Catherine knew she did not have that luxury. If she was going to make sure that the Guise family did not overrun her sons, she couldn’t risk being away from Francis at this point, meaning she needed to quickly say her goodbyes to Henry and accompany the new king to the Louvre.

The Guises could have refused, but truthfully, they needed Catherine. Though Mary–and therefore Francis–loved them, their reputation throughout France wasn’t great. They were fanatically Catholic, which both Protestants and the relaxed Catholics hated, and they were regarded somewhat as foreigners. This is kind of complex because the brothers in question were born in France and were French nobility, but their family had a lot of German heritage–they were descended from the House of Lorraine, which in turn was descended from the House of Metz. And a lot of their prominence was because of Marie of Guise, who though also French, was really part of Scottish nobility. This kind of led to a little mistrust of the family, so having Catherine accompany them made it look a lot more like they had approval to take care of the young king, rather than that they were kidnapping him. It gave them legitimacy.

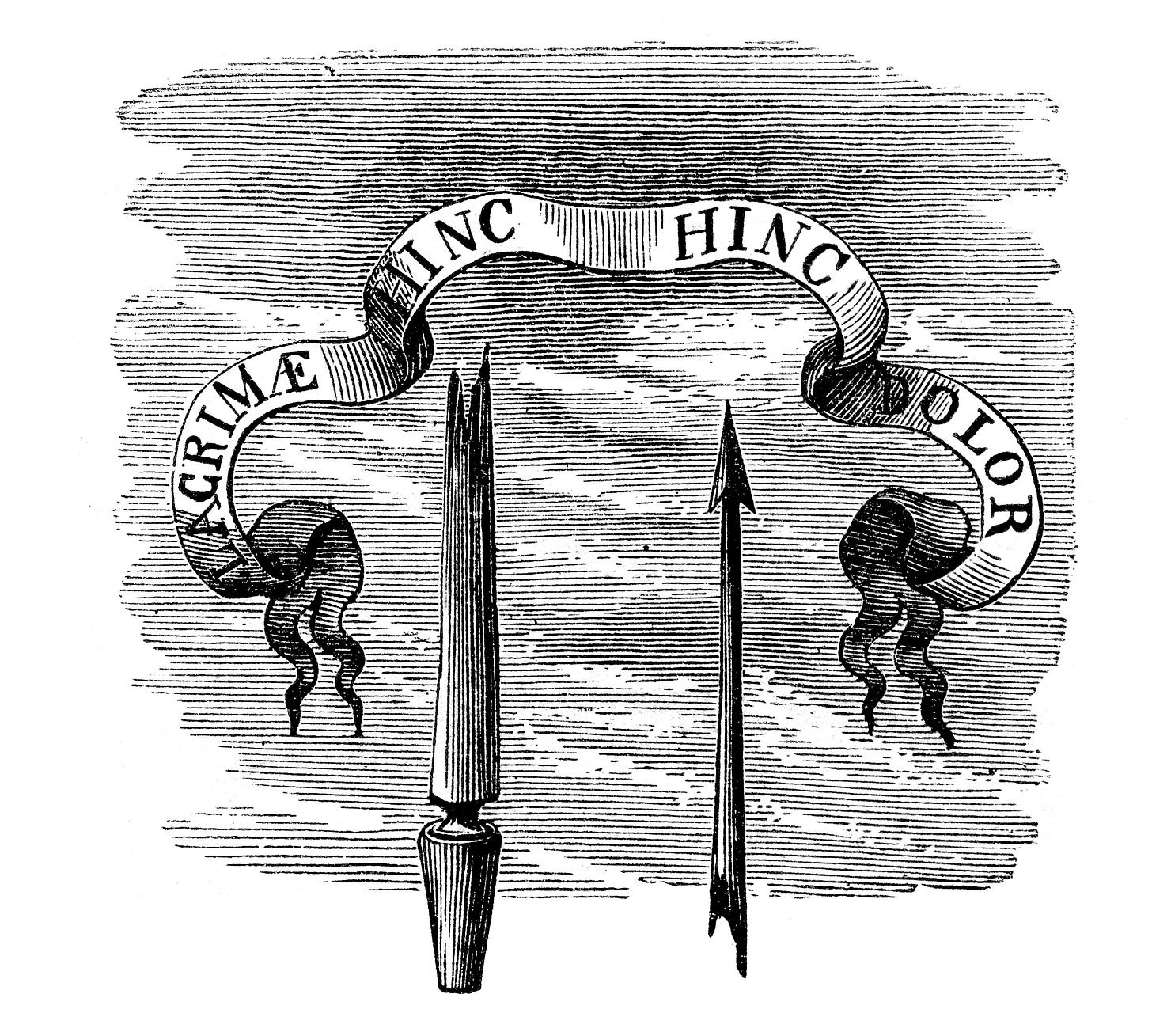

So Catherine went to Paris. In addition to getting involved in matters of state, Catherine also refused the traditional usual white mourning clothes of French queens. She wore sumptuous black for the rest of her life, and she adopted a new motto and crest: a broken lance and the phrase ‘From this come my tears and my pain.’ Basically, she dedicated her life to mourning, and began using her status as the Dowager Queen almost as a weapon, a signal of her power. As long as Catherine entered every room dressed all in black, no one could forget her relationship to Henry. Leonie Frieda, in her biography of Catherine pointed out how this was kind of the first position Catherine ever got to occupy by herself. She had always been forced to share her husband with his favorite mistress, Diane de Poitier, who had used that relationship to amass wealth and power to rival Catherine’s. But only Catherine could be his widow and she really guarded that status of widow jealously for the rest of her life.

Back in Paris, the Guises set themselves up in the best apartments at the Louvre, signaling to everyone that they were the ones really in charge. Catherine, meanwhile, had her rooms redecorated, covering the walls and floor with black silk. Sumptuous mourning is the key phrase here. No daylight penetrated her room, and she kept two lone candles in there to light it–this was the closest she’d get to her traditional seclusion.

Naturally, foreign rulers sent representatives to pay their respects. Many claimed to be, quote, “moved to tears themselves at the sight of Catherine’s utter desolation. Often the new Queen would stand behind her mother-in-law to help with these difficult interviews. Wearing her lily-white wedding dress (the traditional hue of royal mourning) Mary would reply on Catherine’s behalf, thanking the visitors for their condolences and whenever possible managing to insert a flattering reference to her uncles and their ability to help the new King steer France safely forward.”

Henry II’s funeral took place in August 1559, and Francis II’s coronation took place just over a month later.

Francis, at this point, was fifteen years old. Which seems to me much too young to run a country but had he been of good health that would have been what happened. However, because he was physically weak–and also at least seen as mentally weak–a council was set up, with the Guises, Mary Queen of Scots, and Catherine involved. Montmorency, who had enjoyed a lot of power with Henry, was forced out. Catherine did her best to keep Montmorency happy in his forced retirement, knowing she might need to call upon him if the Guises got any ideas about a full coup. Similarly, Antoine de Bourbon should have been at the head of any regency council because of his status as the eldest Prince of the Blood, but he was so slow in making it to Paris that by the time he got there everything had been snatched up. He was given a nominal place on it, but was so outnumbered that it really didn’t matter that he was there at all.

That said, the full council only met once in 1560. Power actually lay with the Guise brothers and Catherine, who made decisions in secret meetings in the King’s chambers, with or without the king. In fact, the newly announced Francis II seemed uninterested in ruling at all, preferring instead to hunt fanatically, though his frail health could hardly take it. In fact, Francis was so uninterested in kingship that all of his official acts began with the phrase, quote, “This being teh good pleasure of the Queen, my lady-mother, and I also approving of every opinion that she holdeth…”

Once the most direct threats to her son’s power were neutralized, Catherine was finally free to get back at Diane de Poitiers. For twenty-six years Diane had lorded Henry’s preference for her over Catherine, taking the best properties and jewelry that should have been Catherine’s by law if they were anyone’s. And yet–Catherine didn’t take this time to do anything to Diane. Diane had to return all the jewels that were technically Crown property, but she did that on her own, and with a listed inventory to accompany it. She also wrote Catherine a letter, apologize for any hurt she caused the Queen Mother and more or less offering not to fight her if Catherine wanted to take everything from Diane. But Catherine had learned well from her own father-in-law Francis I that good monarchs can’t take revenge; quote, “vengeance was the mark of a feeble king and magnanimity a sign of his strength.” Catherine “contented herself” with banishing Diane from court. She also offered to make a trade with Diane–she offered her castle at Chaumont in exchange for the very beautiful Crown property Chenonceau. Technically Diane did not have the right to own this, and had acquired it through some amount of deceit; Catherine had every right to just seize it, but again, she knew that would be worse in the long run, so they traded.

Catherine spent a small fortune beautifying the already gorgeous chateau, and it stands today as a testament to her good taste. She created waterfalls, space for several exotic animals that the Crown had been gifted, an aviary for rare birds, and planted mulberry trees in order to raise silkworms. She also added to the building, adding galleries on a bridge over the River Cher, which you can still walk through today. It’s really beautiful and is a testament to Catherine’s belief that part of keeping a monarchy legitimate in the eyes of the citizens was through big building works that both provided jobs and projected grandeur. Chenonceau did and does both.

It’s worth noting that after this trade, Catherine never saw Diane again, which must have been a relief to her.

In part one, we talked about how the unexpected death of Catherine’s brother-in-law was the first of the poisoning rumors that hang over her reputation like a dark cloud. Well, here comes the second one: A lot of people like to make much of the bad relationship between Catherine and her daughter-in-law, Mary. Most of the plot of Reign, especially in the beginning, revolves around Catherine’s many attempts to get Mary sent back to Scotland, dead or alive. But these are complete fiction–they two women may not have been close, but they were respectful of one another. Upon Mary’s ascension to the throne, Catherine not only handed over the Crown jewels that were then rightfully Mary’s, but she gifted Mary some of her own jewelry–the pearls we discussed in part one. In fact, the two were often found together. They received visitors jointly, shared meals, and attended sermons together. Catherine probably even attempted to teach Mary some amount of courtly intrigue, though Mary didn’t develop much skill for it.

So though the accounts of an antagonistic relationship between Catherine and Mary doesn’t bear up under scrutiny, there are many contemporary accounts of Catherine’s love for the occult. Apparently, before allowing Diane to take possession of the Château de Chaumont, Catherine called on the Medici family’s astrologer and black arts expert, Cosimo de Ruggieri. She asked him to predict the future, so he produced a mirror and told Catherine that the faces of the next rulers of France would appear, and the number of times that each face circled the mirror would indicate how many years they would reign.

It’s said that Francis’s face circled it once, then her second son Charles-Maximilien circled the mirror fourteen times, then her fourth son Edouard-Alexandre’s face circled it fifteen times. (Catherine’s third son, Louis of Valois, had already died when he was only a year old.) Her fifth son’s face, Hercules, never appeared. After Edouard-Alexandre, it showed the Duke of Guise for just “a flash,” then showed Henri, Prince of Navarre, the son of Antoine de Bourbon, who circled the mirror twenty-two times.

As we’ll see, the mirror’s predictions largely came to pass, but of course who knows if these numbers were recorded accurately at the time or if they’ve been amended since that night in order to match what ended up happening. Regardless, Catherine, who had good reason to believe in the occult as several people had predicted her husband’s untimely death, took this prediction pretty seriously.

It’s also said that when Diane eventually entered Chaumont, she found “pentacles drawn on the floor and other sinister indications that the Queen Mother had used the place for her occult practices.” To me this part definitely sounds like nonsense made up to make Catherine look bad after the fact. Men using accusations of witchcraft to delegitimize women happens in all cultures, it turns out. Plus, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, in 16th-century French, the word for pentacle was used for any kind of talisman, which was really common among everyone at this time. It was a superstitious century. And even if she had been inscribing the star inside of a circle that we think of a pentacle today, that symbol didn’t become associated with quote-unquote “devil worship” until a post-Christianity reaction in the twentieth century. The five-point star has a long history as a sacred symbol, sometimes symbolizing the perfect relationship between men, women, and the holy trinity, sometimes the five elements of earth, wind, fire, water, and spirit. It was used in alchemy for the same reasons. It wasn’t associated with evil until probably the 1900s. On top of all of that, if Catherine had been doing some sort of evil magic in this castle, I doubt she would have left that evidence behind for Diane of all people to find. I don’t know who started this rumor, but I have my doubts about the likelihood that it’s true.

In any case, Catherine had several new problems to face throughout 1559: The country was bankrupt after Henry II’s wars, and the Guise brothers weren’t used to this kind of governance. With Francis II spending most of his time hunting, the brothers ended up reneging on loans and deals, cut pensions, and stopped paying salaries to officials and soldiers. The soldiers especially were a mistake–the war they had fought for had been lost, the territories they’d gained just handed back in the treaty negotiations at the end of the war. Suddenly, they were open to ideas of rebellion, and your army is never who you want to rise up against you. Meanwhile, the Guises were sending money, soldiers, and resources to Scotland to protect Mary’s throne from Elizabeth in England, which seemed very unfair to the people of France who were not getting paid for wars already fought. On top of all that, the ultra-Catholic Guise brothers cracked down hard on the Protestants, enforcing increasingly harsh measures on anyone found to be a quote-unquote heretic. Catherine knew that their path would, quote, “ignite an avoidable conflagration.” France was quickly becoming a powder keg, and their new king didn’t have the maturity or force of personality that his father had to hold on them together on will alone.

So Catherine, astutely aware that the Guise brothers would drive themselves out of office, just sat back and watched them ensure their own failures.

Now, Catherine held generally moderate views on the religious debate igniting the country. People in her close circle were Protestant, or had Protestant sympathies, but were not calling for reformation of the Catholic Church or of French policy, and favored a softer approach to solving the religious tension in the country, which seemed like the line Catherine was comfortable at. So as the Guises cracked down, Catherine became popular with the Protestants, who approached her with appeals for aid. In one particular case, Catherine promised to try to convince the brothers to ease up on the persecution as long as Protestants, quote, “did not hold assemblies and that each lived secretly and without scandal.” Which obviously doesn’t seem like a good trade off to us today–clearly it’s not proper religious freedom if you have to practice in secret–but it was better than what the Guises were offering: Death.

In these struggles, Catherine had initially enjoyed support from three women: Her sister-in-law, Marguerite, and two of her daughters, fourteen-year-old Elisabeth and twelve-year-old Claude. But all three were now married and left court one by one. Claude remained the closest to her mother in terms of geography, so Catherine was able to visit her daughter, and eventually her grandchildren, in Lorraine many times over the years. Marguerite was an especially difficult loss for Catherine not only because the two were genuinely close, but because Marguerite was really quite smart and level-headed and as a Protestant she had been able to give Catherine advice on how to better handle the religious conflicts. This was advice Catherine sorely needed, and she was sorry to lose this woman she really trusted. Marguerite recommended that Catherine rely on Michel de L’Hôpital in her absence, who had a reputation as a good lawyer and a humanist, though he didn’t believe the two religions could coexist peacefully in France.

The hardest loss though was of Elisabeth, Catherine’s oldest daughter. Elisabeth, whose marriage to Philip II of Spain, the widower of Mary Tudor, I talked about in the last episode, took Elisabeth away to Spain, a long and arduous journey at the time. Catherine accompanied Elisabeth to the border with Spain, and when they parted, quote, “Catherine’s sobbing was so piteous that even the crustiest onlookers found it hard to remain unaffected.” The two maintained a constant correspondence for the rest of their lives, and a lot of those letters survive, giving us a really lovely look into both of their minds. In these letters, Catherine becomes tender and loving, keeping her daughter updated on everything happening at court, advising her in her marriage, and more–it’s a very different picture than the one painted of her as this menacing poisoner.

In February 1560, rumors of a plot against the Guise regime were made known to Catherine. The Protestants were looking to Louis of Condé, the younger brother of Antoine de Bourbon, as their leader–he was a Protestant, and considered courageous and energetic. Louis didn’t get directly involved, nor did Elizabeth I in England, though both gave their tacit approval of a coup.

It should be noted that it was around this time that people began using the term Huguenots for specifically these French Protestants that followed John Calvin and wanted to see political change, but the origin of the term is highly debated. If you check ten sources, they will have ten to twenty different stories. According to Frieda, the name stuck because these conspirators apparently began meeting at Hugues, a French or Swiss town, but I couldn’t find that city on a map and I didn’t see that story repeated anywhere. Regardless of where the name came from, I’ll refer to them as Huguenots from now on.

So when the Guises got wind of these rebels marching on Blois, where the royal family was living at that time, they panicked. They were convinced that Elizabeth I had funded the plot as retaliation for their support in Scotland–there’s no evidence to support that, by the way–and nothing Catherine or Francis said would calm them. Catherine even urged them to just rescind some of their most brutal measures against French Protestants, sure any sign of softening from the regime might slow down the rebellion.

Her urging resulted in the Edict of Amboise, which offered amnesty for any past religious crimes except to those who took part in any rebellion; it also did not permit full religious freedom, though it did see some religious prisoners freed. She was right that this eased some tension in the country, and it also gave Huguenots hope that she could be relied upon to be lenient with the reform religion in the future.

However, Catherine had a pretty good feeling that Louis of Condé had been involved somehow. Even though he hadn’t marched with the rebels, she knew they needed someone to rally around, and he was the most obvious choice, so she made a move to neutralize him: She made him the King’s chief bodyguard.

Now, this might seem counterintuitive at first glance: Why make a man who probably had more reason than most to want the young King dead that very King’s bodyguard? Well, it was technically a huge honor to be elevated to that position within French court, but it also effectively put Louis under arrest without actually putting him under arrest. He now had to remain by the King’s side at all times, meaning he couldn't go off and plot conspiracies with his Huguenot buddies, and Catherine could keep an eye on him. If Louis realized this is what Catherine was doing–and he probably did–he “affected an air of complete calm” about the whole thing.

In the weeks that followed, the Guises rooted out rebels from around the countryside. Rebels who had been marching in heard that the whole thing was off and turned around; meanwhile, rebels that couldn’t get away were executed pretty summarily. The Guise family wanted to make an example out of them, so they made their executions into displays of power: Rebels were sewn into sacks and dumped in the Loire River to drown or hanged and then their bodies were left to rot hanging from the castle. Catherine tried to intercede on behalf of some of these people, but the Guises were in charge and didn’t listen. Obviously, this did not ease tension in the same way that Catherine’s Edict had.

The worst of it came a week later, when the Guises brothers, with some amount of approval from Francis and Catherine, beheaded fifty-two nobles for complicity with the rebellion. The men sang psalms as they waited, quote, “the sound becoming ever fainters as the heads in the basket piled up.” Though Catherine knew this wasn’t a good long-term solution, she also believed that treason from the nobles couldn’t be tolerated; they had committed treason and put the King and his kingdom at risk.

In part one, I mentioned that Catherine’s Catholicism was undergirded mostly by how she was raised, a love of ceremony and tradition, not so much a solid theological education. And that almost habit of taking the Eucharist had carried her through 40 years of life, but now this gap in her knowledge became an issue because she never fully grasped what the Huguenots’ issues with Catholicism were; she just didn’t have the knowledge to negotiate very tricky theological debates. Obviously today the Protestant rejection of the doctrines of the Eucharist and Papal authority on Earth seem straightforward and clear, even if you disagree with them, but at this point, this was a groundbreaking argument, and Catherine couldn’t or wouldn’t wrap her head around it. And that starts to show here when she was trying to understand why the Huguenots were turning against Francis. She just didn’t get it.

As Catherine predicted, the violent reprisals the Guise brothers had pursued very quickly came back to make the royal family look worse! It was the perfect propaganda weapon for the Huguenots, who were saying that the Guise regime was illegitimate and not in the country’s best interest. They won a lot of converts and foreign support, worsening the religious crisis.

Catherine called a meeting of the full council in August 1560 to discuss what could be done to calm the country. The details are less interesting, but Catherine came away with everything she wanted: the Guises were chastised for their violent handling of the rebellion, with several other council members agreeing that a gentler approach to religious dissension would calm the country down. Catherine was praised for seeing this and trying to act on it in advance, and the meeting ended with several moderate next steps in place. It was a big victory for her.

That said, the Bourbon brothers had not attended this meeting, clearly signaling their belief that the Guise regime was illegal. (Louis had abandoned his post as head bodyguard pretty quickly after the execution of the fifty-two nobles, clearly too nervous to stay in the court.) Rallying continued on around them, and in November 1560 the Huguenots were ready to go on the attack again. They attacked several large towns in southern France.

Catherine, using Francis’s position as King, demanded that Antoine de Bourbon and Louis of Condé come to court at once to explain themselves. And if you’re getting big mom-reigining-in-misbehaving-teens vibes, yeah, I am too. And the two boys, clearly unnerved to be called out so directly, did it–they just went right to Catherine to explain themselves. Louis was of course arrested the second he arrived. There was a sham trial, he was sentenced to execution, and things looked bleak for Louis of Condé. Then he was saved… by Francis’s truly terrible health.

Francis had always been ill, but in November 1560, his health took a sudden dive. He complained of pain in his left ear, his skin was patchy and full of boils, and his face was really swollen and nearly purple. When doctors were called to examine him, they found a fistula in his ear that was causing him agony, but there was nothing they could do about it. They also noted his quote “rotten breath,” saying that it seemed like his body was already decaying. Catherine and the Guises had access to Francis restricted so that the news of his terrible state couldn’t get out, but doctors advised her that it was simply a matter of time before he died. Catherine, who both could see how ill her son was and who also had Nostradamus’s predictions that Francis wouldn’t live to see eighteen living rent-free in her head, certainly had to start preparing for the worst.

And the situation was desperate: her next son, Charles-Maximilien only ten years old, and a regency would have to be put in place for him until he turned fifteen. Catherine feared the possibility that the Bourbons would be put in charge of the regency because if they were they would almost certainly seize power since they were next in line for it anyway.

So Catherine did what she had learned to do best: She manipulated the men around her to make the decisions she needed. She summoned Antoine de Bourbon to her presence with the Guises–and probably the dying King in the next room–and she roundly accused him of inciting rebellion, of treachery, of treason. Well, Antoine, as we all know, was not a great politician, was not particularly quick on his feet nor courageous, and so he, quote, “completely lost his head” in the face of this. Afraid that he would be condemned to death like his little brother, he offered up anything to make the Queen Mother drop these charges: Including his spot on the regency council. She quickly made him sign a document saying that this was the case, and the Guises witnessed this with growing horror because suddenly, they were realizing that their sham trial of Louis had been a huge mistake. With the next Valois boy in line not married to their niece and therefore not biased toward the Guises as Francis had been, their position became tenuous. It would not be hard for them to be thrown down as they had thrown down Montmorency the year before.

Seeing their fear, Catherine offered them an out too: Francis could lie and say he had ordered the arrest and trial of Louis of Condé *if* they agreed to let Catherine head up the regency council for Charles. They agreed, and then Catherine made the Guises and Antoine hug each other, a, quote, “meaningless gesture as part of a formula for ‘reconciling’ her enemies” that Catherine did a lot.

Her future at least temporarily secured, Catherine returned to Francis’s bedside in time to watch the abscess in his ear spread into his brain. He died an agonizing death on December 5th, 1560, leaving Mary a widow and Catherine as Queen Mother and Regent for Charles, though her title technically became Governor of the Kingdom. Her regency was confirmed the very next day, and Charles was declared Charles IX. Antoine de Bourbon and the Guises were made to publicly proclaim their loyalty to her, in speeches that she probably wrote herself in the few days leading up to it. Naturally, Antoine and Louis left town as soon as possible.

The country had been through a lot of instability: Charles was their third monarch in seventeen months, and Catherine, who had been a constant presence in the royal family for nearly thirty years, became the most familiar face and symbol of continuity for the French people. Still in her mourning dress, she represented a matronly figure for a nervous country, much the same way that Queen Victoria of England would do a few hundred years later.

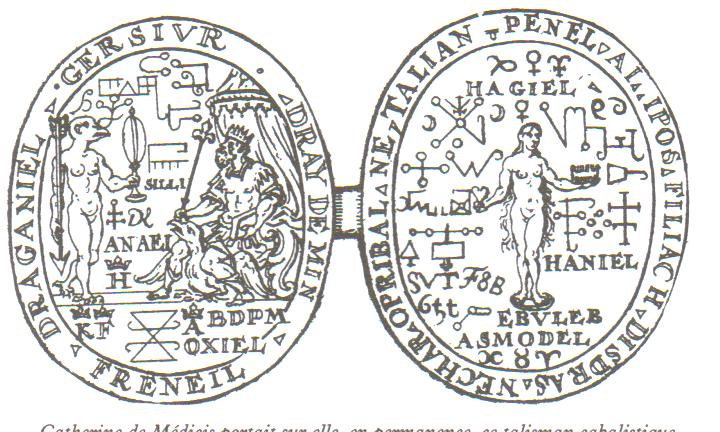

Catherine continued to consolidate power. Importantly, she created several symbols that could reflect her new role for the kingdom, including a special seal that apparently depicted Catherine standing, her crown and widow’s veil obvious, holding a sceptre in her right hand while her left raised with the index finger pointing as if commanding. I couldn’t find a surviving image of this, but I did find other talismans that are *supposedly* linked to Catherine de Medici, and those are in the transcript on Substack.

Through her role, she began to open mail in front of her son, the king. Any letter from him was accompanied by a letter from her, confirming that his order was the right one. She also began to hand out the rewards and offices that were usually a monarch’s sole will, but Charles had four years of regency to go–Catherine needed to be able to hold on to power for at least that long. The two spent a lot of time together, though. Catherine continued to ride and hunt with Charles as she had with her husband and his father. Clearly, she saw how this sort of somewhat masculine pursuit gave her better access to the male rulers in her life that other women couldn’t have if they wouldn’t participate. She also loved to exercise in general though and kept much more active than normal women of the time. She also, uh, slept in Charles’s room every night, and wouldn’t allow anybody else to. I think mostly out of a desire to protect him.

She brought her sister-in-law’s recommendation along for the ride in her growth of power: Michel de L’Hôpital. Through his legal education, she managed to learn how to turn the good instincts she had about people and ruling into good state policy. With his tutoring, to some extent, Catherine quote “acquired a polish and gravitas that frequently left her listeners surprised and impressed.”

In fact, Estates-General meetings that had been planned under Francis went on as planned. The changing of the King had not changed the fact that France was bankrupt. The Estates-General were rarely called on at this point in French history, largely because their only use was to, quote, “present grievances to the King and the voting of money,” which, you know, who wants that? But Catherine needed financial support from the nobles to ease the pressure of the crown’s empty treasury.

The Estate-General was made up of three bodies: the nobility, the clergy, and the commoners. When the crown was weak, as it was then, the Estates-General found itself with more power. That said, the commoners at this time had already been taxed into starvation, so Catherine was basically asking the clergy and the nobles to help the Crown raise enough funds to give the Crown back its independence–clearly “an audacious proposal.”

The financial problem wasn’t resolved, but Catherine did push through other important measures. One was a unification of weights and measures, and a taxation of moving goods within France was abolished. They also cracked down on abuses by the church and the judiciary, putting into law that magistrates had to be elected, which is pretty interesting. This protected commoners more than anyone else. And today in French law some judges are still elected, though obviously, the position has evolved over the last 500 years.

Importantly, this moment saw Catherine clearly denounce the violent persecution of Protestants that had happened at the hands of the Guise brothers and her husband. “Gentleness will accomplish more than rigour,” L’Hôpital was heard to say on Catherine’s behalf. Unfortunately, the Protestants misunderstood this small measure of toleration–they were given an inch and thought it meant they could take a mile. They became, quote, “ever more brazen in their open practice of the new religion and magnified Catholic fears by damaging church property, smashing sacred statues,” and more. Catherine wanted to prevent Church abuses against Protestants, but more than that she wanted people to live peacefully to ensure that her son remained on the throne. As Frieda writes, “[Catherine’s] moderation was directly proportionate to what she believed to be politically expedient.”

However, her moves toward religious tolerance, however politically-motivated they were, those moves were received very badly by other Catholic monarchs, especially Philip II of Spain, her son-in-law. A strident Catholic himself, he believed it was his sacred mission to rid the world of the Protestant “threat,” and he did not take his neighbor’s modicum of religious tolerance well. He sent advisors and letters scolding her, and she wrote back, quote,

“For twenty or thirty years now we have tried…to tear out this infection by the roots, and we have learned that violence only serves to increase and multiply it, since by the harsh penalties which have been constantly enforced in this kingdom, an infinite number of poor people have been confirmed in this belief…for it has been proved that this fortifies them… consider the season in which we live, and in which we are sometimes obliged to dissimulate many things which in other times we should not endure, and for this reason to pursue a course of gentleness in this question…may preserve us from the troubles from which we are only just beginning to emerge.”

In a way, she’s kind of espousing what some parenting methods teach: Cracking down is still a form of reward for bad behavior. It’s like rewarding a tantrum. Instead of punishing bad behavior and therefore acknowledging it and essentially giving them the attention they’re really craving, why not just ignore it and see if that means they lose interest in rebelling? She’s treating commoners especially like they’re small children, which was not an uncommon approach for leaders then or now. As we’ll see though, Catherine’s attempts at this approach never really got to be fully explored.

Speaking of parenting, Catherine was lenient about the religious education of her own children–they had access to both Catholic and Protestant literature if they wanted it, and it was said that her son Edouard-Alexandre knew Protestant psalms that he could recite from memory. He even called himself, “un petit Huguenot” and mocked imagery of the saints. I mean, he’s ten years old at this point, and probably behaving like any ten-year-old kid, which means pushing boundaries and seeing what he can get away with. He and his friends once dressed up as cardinals, bishops, and abbots and burst into a meeting Catherine was having. They were riding a donkey, clearly mocking these religious leaders and Catherine laughed at the joke, which she then had to backtrack on when it upset people–she basically used a 16th-century version of boys will be boys to excuse their behavior. She knew they were curious and allowed them to be, instead of making it forbidden and therefore much more interesting. So how much of Edouard’s behavior is truly religious conversion and how much of it is simple boyhood rebellion is hard to say. But certainly, people around Catherine noticed this and did not love it and she eventually had to crack down on him not because she was worried about his eternal soul but because this was contributing to the religious fissures in the court.

Because it wasn’t only Philip of Spain who was upset. Suddenly Montmorency and the Guises, who had long disliked each other, had something in common: A desire to protect the Catholic faith in France. They came together and formed the Triumvirate in April 1561, with financial backing from Philip. So grumpy were they about Catherine’s path of moderation that they originally weren’t going to attend Charles’s coronation the next month, and had to be talked into going by Pope Pius V who pointed out that if there were no Catholics around Charles, then he could hardly be blamed if he fell under the sway of the Protestants.

At said coronation, eleven-year-old Charles cried because o the weight of the crown. Like Francis, he was physically very weak and, quote, “presented a pathetic image, a physical incarnation of the monarchy’s present weaknesses.”

Unfortunately, Catherine’s movement toward conciliation did not have the impact she hoped. It just made her look weak to everyone–Protestants wanted more tolerance and Catholics grew more belligerent in their fear of the heretics. Perhaps frustrated by increasing demands from the Protestants, in July Catherine issued an edict pardoning all religious crimes up to that point if the people led, quote, “peaceful and Catholic lives” thereafter, which went back on earlier more tolerant edicts.

During this same summer, the Church offered Catherine nine million livres to settle the King’s debts and to buy back royal domains. I would bet this sum was offered at least in part because the Pope was very nervous about Catherine’s upcoming Colloquy of Poissy, a religious conference that intended to negotiate peace between Catholics and Huguenots in France. He feared that Catherine inviting the Huguenots to the table gave them and their faith legitimacy at the very same time that he was trying to restart the Council of Trent that had paused indefinitely back in 1552. He wanted Catherine to pull back on this, and probably the financial help was meant to make her feel indebted to the Catholic Church, but she still moved forward with her original plan.

The Colloquy of Poissy did not produce the healing Catherine hoped for. Huguenots and Catholics could not come to peaceful resolutions, and in fact, the Catholics called for full banishment of the quote-unquote heretics from the realm. She barely came out of it with her own security intact, as the Catholics also questioned her judgment at allowing her children to attend and hear the debates, thinking them too “tender” for it.

Catherine didn’t follow Catholic recommendations. Frieda puts her preference toward toleration down to something very simple: While the Catholics bullied her, called her names, and threatened her, the Huguenots were very respectful to Catherine, lauded her wisdom, and appealed to her as their ruler. It seems very obvious in retrospect that of course, Catherine was going to side with the people who were nice to her!

The Guises also made the incredibly stupid move of trying to kidnap Edouard-Alexandre, the presumptive heir, at this point. Catherine openly favored this son, and she also clearly remembered how the Guises had basically kidnapped Francis, so this move did not go over well with her. However, as was her habit, she bore it quietly, waiting for the moment when she could use this mistake against them.

Meanwhile, violence kept breaking out between Huguenots and Catholics. In January 1562, Catherine tried to issue another edict for peace. This one recognized and legalized the Protestant religion in France, allowing Protestants to become citizens once again–before this, you had to be Catholic to be a citizen of France. Their citizenship was second-class at best, but it was a big step toward religious freedom. Obviously, everyone was mad about it and it took a long time to get ratified, though Catholics still advocated for it to be revoked. Philip sent a letter through Catherine’s daughter Elisabeth saying that if Catherine continued on this path, she could expect Spain’s enmity. Meanwhile, Louis of Condé finally stepped publicly into the role of leader of the Huguenots, which only fortified them.

And then the powder keg lit. The Duke of Guise was in Vassy, in the Champagne region, on Sunday, March 1, 1562. He rode to Mass with an armed escort and they happened to hear singing coming from a barn–it became quickly clear that a Protestant service was taking place inside. Catherine’s edict allowing this had been issued two months before, but it wouldn’t be ratified for five more days, so technically this service was illegal still under the previous edict banning Protestant gatherings.

What exactly happened next is not known for sure, though we can guess pretty well. The Duke’s official account is that there was, quote, “a regrettable accident” that brought his soldiers and the Protestants into contact. An accident seems, uh, extremely unlikely, given everything we know about the Duke of Guise. There’s kind of an understanding that, in fact, the Duke was only in Vassy because his mother Antoinette had complained about the spread of Protestantism in and around their lands, and the Duke had gone searching for these services. And that seems like the simplest answer, because the idea that the Duke heard Protestants singing over the pounding of the hooves of a hundred horses riding by is truly laughable. He would have had to have his ear pressed to the wall of the barn. Also, why did he have so many soldiers with him just to attend Mass? Why was he attending Mass so far away when there was surely a chapel much closer to his own chateau… His version of events doesn’t make sense. Which makes what happens next all the worse.

Basically, according to the Duke, they came into contact on accident and tempers just boiled over and someone else threw the first punch, and oh my gosh, how horrible, who could have predicted???? This historical incident is remembered as the Massacre at Vassy, because what probably really happened is that the Duke and his soldiers attacked the barn first, killing seventy-four Protestants and injuring over a hundred more. Among the dead were many women and children. The Duke sustained a minor injury to his face, which is probably the only reason he admitted to being there at all–he couldn’t lie about where he’d gotten a knife slash across his cheek. But none of his men died, which tells us that the Protestants probably weren’t armed when they were attacked.

This is the beginning of the French Wars of Religion.

The Duke rode quickly to Paris, one of the most staunchly Catholic cities in the country, with 3000 soldiers in tow. They were hailed as heroes of the Catholic faith. Louis of Condé was already there with 1000 of his own Protestant soldiers, and things looked bleak.

Catherine was at Saint-Germain when she heard, and she had to rush to stop open warfare from breaking out in Paris. She issued orders for both Guise and Condé to leave Paris at once and take their soldiers with them since they had no right to raise an army right then anyway. Guise did nothing because he knew the citizens of the city had his back, but Condé wisely fled. Catherine moved the court and her boys to Fontainebleau, but the Guises caught up with them, once again taking the King of France into their quote-unquote “care” at the Louvre, using the old excuse that someone else was going to hurt the royal family. Catherine tried to stop this because she had seen what happened with Francis and how the Guises had seized control once they seized him, but once again she couldn’t stop them.

Meanwhile, full-scale fighting broke out around the country, with Condé taking Orléans and Rouen a few days later. It was now officially a civil war, with the Huguenots essentially rising up as rebels. On April 8, Condé released a statement, saying he only wished for religious tolerance for his people and to free the royal family from the influences of the Guises, which must have struck Catherine particularly hard in that moment since they were essentially being held captive.

Now Catherine did something very brave here. She rode out to negotiate with Condé herself. Confident that he wouldn’t harm his cousin, however distantly related they were by marriage, she rode out to Toury herself and sat down for negotiations. They didn’t really get anywhere, and she left with her hands empty, but I think this says a lot about who she is.

Obviously, foreign powers got involved. Philip, delighted at the prospect of France ridding itself of this Protestant menace, sent 10,000 foot soldiers and 3,000 cavalry. Elizabeth I also got involved, sending 6,000 men across the English Channel to Condé, though her goals were less religious and more pragmatic: She wanted the Guise family to fall, hopefully taking Mary Stuart in Scotland down with them.

The war was particularly vicious, with a lot of settling of old scores happening. Monks had their throats cut, 200 Protestants were drowned, a lot of people were being decapitated on both sides; even Francis II, Catherine’s recently deceased oldest son, did not escape unscathed–his tomb at Saint-Denis was broken into and his heart burned; other royal tombs were desecrated as well. And of course, each atrocity begot five more.

In October of that year, Catherine once again set out for the front of the fighting. She went to Rouen to see the progress the royalist (and therefore Catholic) armies were making. She listened to the military experts debating what to do next, and even walked upon the ramparts, though Guise and his new ally Montmorency warned her not to. She apparently laughed and said, quote, “My courage is as great as yours.”

They weren’t just being protective–Antoine de Bourbon, King of Navarre, was there as well, having declared himself for the Catholics and against his brother Louis. He was hit in the shoulder and died there, leaving the throne to his wife Jeanne, who had been the actual bloodline inheritor of the throne anyway. This is interesting because Jeanne was a Protestant, so Antoine’s death changed the Kingdom of Navarre’s allegiance in the war. In her mourning, she tried to stay relatively neutral, but this war certainly dragged her in eventually.

Antoine’s death also provoked another fear in Catherine. His young son Henri, just eight at the time, had been predicted to be King of France by those soothsayers at Chaumont. Seeing him go to Navarre to learn how to rule from his mother made Catherine very nervous.

When the royalists recaptured Rouen, the royalist soldiers slaughtered 4,000 rebel captives. Even the Duke of Guise tried to stop this, perhaps finally realizing after his own massacre at Vassy that blindly murdering groups of undefended people doesn’t make you friends.

I’m not going to go through every battle of the first War of Religion because we’d be here for years. But suffice it to say that fighting carried on around France into 1563. The Duke of Guise was assassinated in Orléans in February 1563, shot in the back while he was on horseback. The assassin had supposedly been hired by Admiral de Coligny, who was fighting on the Huguenot side. The assassin was executed before the full truth of what actually happened ever came out, though historians tend to think that Coligny probably was not directly involved. This murder started a feud between the Guise family and Coligny family that would have devastating consequences down the road.

Of course, the Duke’s death had to come back to Catherine though. I can see why this time–the Duke of Guise had essentially held two of her sons hostage at this point and was trying to grasp at power again, threatening her family’s future. Allegedly, she told the Marshal de Tavannes, “The Guises wished to make themselves kings, but I stopped them outside Orléans.” Supposedly she also later told Condé that, quote, “Guise’s death released her from prison as she herself had freed the prince; just as he has been the duke’s prisoner, so she had been his captive given the forces with which Guise had surrounded her and the King.” That bit about freeing the prince is a reference to when Prince Louis of Condé was arrested by the Guise family during Francis II’s reign. Even the Venetian ambassador claimed that Catherine told him, quote, “If M. de Guise had perished sooner, peace would have been achieved more quickly.”

And peace was kind of achieved really quickly after his death. Both Montmorency and Condé had been captured in the fighting, so Catherine made the two leader-prisoners hash out a peace so that they could be released. The result was the Edict of Amboise on March 19, 1563. It made a lot of concessions to specific noble Protestants, but not commoner Protestants. Specifically, noble Huguenots were able to hold services on their estates, but commoners could only worship at home; there weren’t going to be independent Protestant churches. But freedom of conscience was granted to all the Huguenots, and, as with every edict before this, both sides thought it wasn’t enough.

So did Catherine have the Duke of Guise assassinated so that she could broker this peace? I don’t know. For some reason, this accusation, of all the accusations against her, seems the most possible to me for three reasons: One, because he had basically started this whole war with the massacre at Vassy; Two, because of how quickly she made sure the assassin was silenced; and Three, because of how dangerous the Duke had proved himself to be to her family over and over again. I don’t think Catherine ever killed for ambition, which is what she’s often accused of, but I think revenge and some idea of ‘the greater good’ might have been a potent enough combination for her. Of course, we’ll never know.

With peace brokered, Catherine turned her attention once again to uniting both sides of the country. And this time, she had a common enemy to hand to them: In all the fighting, Elizabeth I had taken Le Havre, which was not only an important port city in Normandy, but also was conveniently where the River Seine, which runs through Paris, met the English Channel. If the English wanted to launch an attack on France, holding this port made it easier for them to get to the capital, which meant Elizabeth needed to be expelled.

It worked. Catholics and Huguenots joined together and kicked English troops out of Le Havre by July 1563. Catherine and Elizabeth agreed to peace terms the following April. For a while, things were quiet.

Catherine decided it was a good time to take a page out of her father-in-law’s book. She publicly reconciled with Condé and began to keep the court entertained with balls and masques. She correctly predicted that if they were too busy having fun, they wouldn’t have time to plot to overthrow her son or start another war.

This is also when Catherine formed her famous Flying Squadron. She had previously been very strict with the ladies of the court, instantly dismissing anyone who was rumored to have loose morals. But now she, quote, “happily availed herself of the charms of the loveliest maidens of high birth.” Numbering anywhere from 80 to 300 girls, they were dressed like goddesses at all times and while Catherine insisted that they behave with decorum in public, in private, they were free to do as they wished, quote, “provided they had the wisdom, ability and knowledge to prevent a swelling of the stomach.”

Catherine taught them to use their feminine wiles to basically keep the men at court complacent. This may sound simplistic, but it worked. At one point, Prince Louis of Condé fell so in love with one of Catherine’s members of the squadron that he stopped going to Protestant services and returned to Catholic worship for her. This is how good they were.

Suddenly, Catherine’s court, weak and on the verge of collapse a year before, was becoming famous for being a place people wanted to be. She continued to wear her black mourning clothes, and now in her mid-forties, she still wasn’t considered a great beauty, but she was quote, “witty and strangely alluring; even her sternest critics…could be momentarily seduced into appreciating her qualities.”

Outside of court though, people were still exacting revenge after the war. Catherine was called on to arbitrate disputes, which she tried to do tactfully, but the constancy of it wore on her. Contract murders not only became more popular but also gained the disheartening nickname “vengeance in the Italian way,” a good indication that for all that Catherine was a familiar face in France by now, many never forgot that they were being ruled by a foreigner.

So Catherine opted for a cosmetic change for the throne: She had Charles IX declared of age, even though he was only thirteen. She was gambling: Even though he was young, he was the actual monarch, not a regent, and she thought that the nobles might be more likely to be loyal to him. Of course, she continued to actually rule.

Charles, at the time, was an “essentially kind and generous-hearted boy,” though that fell away as his own health problems took their toll. Like his brother, Francis II, he had a tendency to push himself too hard while hunting and had trouble recovering from those exertions. He also had a morbid fascination with dead animals and was known to pull apart the animals he hunted with his own hands; if you watched Reign and remember the strange accusations that Charles was eating people and raw flesh, those were rumors borne of this interest that his own courtiers found off-putting. He was not interested in women, Court entertainment, drinking, or dancing. His health problems became full health crises, eventually, and he began to go a little mad until he eventually began to fly into rages that left courtiers afraid for their safety. But for now, that was all in the future.

Despite the Church’s previous loan that I mentioned, Catherine struggled to keep up with Court finances. She insisted upon grandeur all around them at all times, as part of her belief in projecting grandeur to inspire awe and worship. The court was also 10,000 people strong, bigger than most towns in France; those people all received some amount of payment, which kept the royal coffers constantly low.

The Court also constantly had to move, not as part of some progression to show off the King, but actually because their presence would empty a whole city of any of its food. The lack of sanitation also was an issue–10,000 people produced a lot of waste, and after a few weeks that stench became unbearable, as did the accompanying risk of disease.

Though Catherine did actually decide at this point that Charles needed to see the kingdom and–more importantly–they needed to see him. She believed that, quote, “bringing the splendour of the monarchy to the drabbest corners of the kingdom” would encourage some love between the people and the king. Her plan was for 28 months of travel, which would hopefully help heal some of the ongoing wounds left over from the civil war.

Their progress began in January 1564. They wouldn’t return to Paris until May 1566. As this was beginning, the Pope’s Council of Trent finally broke up, bringing unwelcome news: It would be forever impossible to reconcile Catholicism with Protestantism, making the schism final and irreparable. Everyone probably knew this was where this debate was heading, but Catherine had hoped to avoid it. Moreover, the Papacy was trying to enforce the Pope’s standing as supreme ruler on Earth, over the power of the French Crown (and other heads of state as well). This infuriated Catherine, who didn’t believe the Pope had a right to enforce rule over matters that she saw as Crown business. When he then charged Queen Jeanne of Navarre with heresy, Catherine defended her, saying the Pope had no right to rule over foreign heads of state who had been put in their positions of leadership by God. Pius, unwilling to drag Italy into yet another war with France, dropped the matter, but staunch Catholics in France noted how quickly Catherine had defended the Huguenot queen.

To thank Catherine, Jeanne and her son Henri joined their progress for a while. When Jeanne was ready to go, Catherine said she could go, but that Henri must stay. Jeanne probably didn’t love this, but Catherine probably played the family card–Henri needed to get to know his cousins. In any case, Henri wanted to stay because he was a kid and the progress was exciting, and playing with his cousins was much more fun than going to church every day with his mom. So Jeanne left but Henri continued traveling with them.

The tour progressed. Catherine was more relaxed and happy than she had been in years, which we know because she used this time to play a prank on Montmorency. She sent him a message saying there had been a massive change in the tour schedule and that she’d decided to go to Barcelona, which sent him into a “blind panic” until he found out she was kidding.

In October 1564, Catherine met with Nostradamus in Provence. He was quite old by then and suffering from gout, but he came out to meet the royal family anyway. His first prediction was that Charles would outlive Montmorency, which comforted no one since Montmorency was in his seventies. Nevertheless, Catherine brought him on to the royal payroll, making him a royal councilor and the king’s physician. Nostradamus apparently took an interest in Henri, watching him for a couple of days before declaring to his servants, quote, “You will have as a master the King of France and Navarre.” Catherine probably didn’t love hearing this either!

There was one part of this route that Catherine was particularly eager for: A meeting between herself and Philip II along the French-Spanish border. She’d been trying to negotiate this meeting for six years, but he had rejected it for the same reason he’d refused to come to Paris to marry her daughter Elisabeth: the Spanish monarch couldn’t be seen leaving Spain! He had initially agreed to this meeting but backed out because ultimately he didn’t trust her. He had nicknamed her “Madame La Serpente,” because she was notoriously elusive and opaque when he wanted her to be firm on issues of faith. Philip was also annoyed that Catherine was launching an expedition to the Americas, which he thought should be plundered and destroyed by Spain alone. Finally, he had heard that Catherine had received an emissary from the Sultan of Turkey, a nation he viewed as even worse than the Protestants; a feat, really, considering Philip’s fanaticism. In the end, he did allow her daughter Elisabeth to travel to meet her though, which delighted Catherine.

He also sent the Dukes of Alba and Alava to scold Catherine. Alava in particular would become a constant thorn in her side.

But Catherine was very touched to have Elisabeth back. It’s said that they both “cried when they first met.” However, her time in Spain had changed Elisabeth, and she had adopted very Spanish mannerisms. Her husband had indoctrinated her very thoroughly–unsurprising, since she’d gone to him at like thirteen years old–and she had grown up to be little more than a parrot for his opinions.

Both Elisabeth and the Duke of Alba brought a worrying concern to Catherine’s attention: Philip would begin attacking French Protestants living close to the Spanish border if Catherine didn’t do something about them herself. He was worried they would “infect” his people with their heresy, and he wasn’t afraid to take drastic measures to prevent that. They eventually gave up on their negotiations, having agreed to nothing.

Catherine had arranged for a spectacular show for the Spanish visitors though. They had sumptuously decorated barges to look like stage set pieces, and enacted a show of a whale and tortoise fighting Neptune and Arion on the water, capped off by three women dressed as mermaids singing songs to glorify Spain and France. Though many monarchs of France would be known for their theatrical displays, it was Catherine who really inaugurated the use of these spectacles to display the crown’s wealth, power, and unity.

The Spanish were resentful of the display though. Philip’s austere fashions at court and utter bankruptcy from his own wars made them look shabby next to the sumptuous French court, and they hadn’t even won anything in their negotiations. They left more or less annoyed. Catherine never saw Elisabeth again.

Their two-year progress drew to a close after this. When they returned to Paris in the spring of 1566, Catherine was sure that they had built a foundation for lasting peace in France. She was not right.

That summer, violence broke out in the Spanish-controlled Netherlands. There, Philip had used the violently oppressive techniques he had recommended to Catherine in order to silence the Protestants. It had erupted into outright violence, and civil unrest drew worryingly close to the French border. Catherine was feeling smug about this but had little right to–tensions were growing in France again. The source this time was the many formerly Catholic prelates who had converted to Protestantism but were still receiving huge income from the Catholic churches they were nominally in charge of. Previously moderate Catholics were very frustrated by this.

Huguenots in France, feeling protected by Catherine, started agitating for aid to the Protestants in the Netherlands. It was suggested by some that France should come to their aid, because it could only benefit France if they managed to kick Spain out of this region and take it for themselves. Catherine emphatically said no to this and forbade any help.

Then Philip infuriated Catherine: He left Spain at the head of 20,000 troops to put down the violence in the Netherlands, which would bring him very close to the French border. With his very recent threat to attack French Huguenots himself probably ringing in Catherine’s ears, she and Charles immediately got nervous and began reinforcing their northern border. They hired 6,000 Swiss mercenaries to station there, just in case.

Well, THAT made the French Huguenots nervous, wondering if there might be a secret plan between Philip and Catherine to use the Swiss army on the French Huguenots once he was done in the Netherlands. By the summer of 1567, when the Swiss mercenaries were still in France, the Protestants began attacking Catholics. Catherine, who had never had any intention of turning on her own citizens, and in fact had been favoring the Protestants for a while by this point, was very frustrated by this turn of events. Catherine did her best to assure Condé and Coligny that nothing was up, but the reports of the increasingly violent repression happening in the Netherlands did not calm anyone’s nerves.

Catherine, for once, was not following her instincts. She was determined to believe everything was fine, and she kept telling everyone that, even though there was mounting evidence that things were devolving in France. The Huguenots were so convinced of their own imminent danger that they began planning a preemptive strike, and Catherine was even warned of this, but she kept brushing it all aside until she no longer could because troops had been spotted marching her way.

She called the Swiss troops away from the northern border to her, and she and the Court made a mad dash to Paris, surrounded by Swiss troops. It was not dignified in the least. Catherine professed to be surprised by all of this, so she sent her reliable Michel de L’Hôpital to negotiate with Condé. His demands were that the King disarm entirely, that all taxes be lowered, and that the Estates-General be called immediately. He presented himself as, quote, “a hero of the downtrodden people.” The rebels surrounded and blockaded Paris, ensuring unrest and starvation within.

At this point, the days of Catherine’s hopes for the peaceful coexistence of Protestants and Catholics finally ended.

And with that opening salvo of the second French War of Religion, I’m going to end part two of this story. I really thought that we could do this story in two parts, but it really deserves to be a three-parter. In part three I’ll cover the final days of Charles IX, the reign of Henri III, and of course, the end of Catherine’s life. We leave her here at the height of her power, and what comes next is the darkest period of her life.

📚 Bibliography

Books

Frieda, Leonie. Catherine De Medici: Renaissance Queen of France. Harper Perennial, 2003.

Share this post