Hey everyone,

Freddie Oversteegen is one of those women whose photo floats around on the internet a lot. Her story always gets a lot of attraction in simplified social media posts about seducing and killing Nazis, which is how I first heard of her. But after years of doing this podcast, I had to wonder: What’s the reality behind her story? Did she really seduce Nazis to kill them? It sounds like the stuff of Hollywood legend. So here’s her story.

🎙️ Transcript

In grade school, the history we were taught about defeating the Nazis centered on national military movements—the Allies coming together against the Axis Powers to end Hitler’s takeover of Europe, free people captured in concentration camps, and try to end fascism. However, left out of that story of Allied success are the individuals who fought back from day one. Inside the invaded countries of Europe, people came together in small groups to fight back against the Nazis—they spread anti-fascism pamphlets, disabled Nazi supply lines, damaged Nazi factories, and some people even assassinated Nazis.

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Castellanos Clark, and today I’m covering the tale of Freddie Oversteegen, a woman who has gained posthumous fame for assassinating Nazis after they invaded the Netherlands.

Before we jump into this tale of assassinating Nazis, I first have to thank all of the paying subscribers on Substack whose patronage helps me make this podcast possible. If you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber over on Substack! When you upgrade, you’ll get access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com

All right, let’s hop into it.

Freddie Oversteegen was born on September 6, 1925 in Schoten, Netherlands. She had an older sister, Truus, and the family moved around a lot during their childhood, living in unlikely places like houseboats, horse wagons, and more1. Freddie’s parents divorced when the girls were young—her father, Jacob, sang them a “farewell serenade in French” for the occasion.2 He remarried and moved away, and it seems like the girls didn’t have much contact with him after that. Their mother, Trijntje, moved the family to Haarlem—the city in the Netherlands, not the neighborhood of New York—where she became involved in the local Communist party.

The family—mostly their mother—was part of International Red Aid, a social service group organized by the Communist International. Through that group, the Oversteegen girls made dolls for children caught up in the Spanish Civil War. Also through Red Aid, as early as the mid-1930s, Trijntje was inviting Jewish families fleeing Germany to take refuge in the family’s apartment. However, as Communism became a bigger source of panic and invited surveillance in Western Europe, the family had to stop hosting Jewish families, fearing that their known Communist sympathies would end up revealing the families they were trying to save.

That is, unfortunately, basically all we know of Freddie’s early childhood. When World War II officially erupted on September 1, 1939, she was only 13 years old. Her sister Truus was 16, and their childhood ended with a weighty question: Adapt or resist? An estimated 90% of the Dutch population attempted to adapt and live their lives as normally as possible under Nazi occupation.3 Of the ten percent left, roughly half were Nazi collaborators and half were members of the Dutch resistance. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given what we’ve talked about so far, the family leaned toward resistance.

From the beginning of the war, the Oversteegens printed illegal magazines in their living room, but it was so loud that they had to have lookouts to ensure they weren’t caught.4 Truus and Freddie were frequently found graffitting pro-resistance slogans on walls; fortunately they were never caught by soldiers, just friendly neighbors.

Early in 1941, they were drawn into the Resistance more formally. Frans van der Wiel, Regional Commander of the Council of Resistance of Haarlem, knocked on the door and asked Truus and Freddie to join them and participate in more “serious forms of resistance,” like sabotage.5 The girls were initially reluctant, because they weren’t used to older men being interested in them, but they met with him again. This time, he pulled a gun on them and said they’d been set up: He was Gestapo, and if they didn’t give up the address of a certain Jewish man, he’d arrest them.6 Instead of getting scared, they attacked him, kicking and hitting him! He cried out that it had just been a test and that they had passed: They were officially part of the resistance.

Two teenage girls were ideal candidates. Since most armed resistance work was done by men, no one suspected them. Both were young—and Freddie looked even younger—so soldiers just couldn’t see them as a threat. They could more easily carry messages or guns without their bags being searched. They burned down a Nazi warehouse without being noticed.7 For two years, they worked like that, passing by unnoticed.

By the summer of 1943, it was no longer safe for the family to remain in Haarlem. By then, their neighbors knew they were printing illegal anti-Nazi newspapers and had some idea they were working in the resistance. Their mother moved to Epe, living on the farm of a man named Mr. Volkerink, whom Trijntje later married after the war. Freddie and Truus moved to Enschede, where they worked as nurses in the Evacuation Hospital.

This is when they met Hannie Schaft, one of the most famous members of the Dutch resistance. Hannie had already joined the resistance, interviewed and tested by Frans van der Wiel in much the same way the Oversteegens had been. Freddie later admitted that she was a bit jealous of Hannie—their status as the only young women in the resistance was somewhat lessened by her appearance.8 But they eventually came to work together well: Hannie was the intellectual, Truus the leader, and Freddie the planner who would map everything out in advance.9

Around this time, one of their new missions became to act as “Moffen girls.”10 “Moffen girls” were Dutch girls who had relationships with German soldiers, based on the Dutch derogatory term “mof” for German soldiers.11 The girls had never really worn makeup before this, so they had help from Frans van der Wiel to dress them up and help them with their makeup, including bright red lipstick that Freddie later said made them look “ridiculous.”12 But it worked!

The girls began flirting with German soldiers and officers to get information out of them. This is how they managed to map the Atlantic Wall, which was “5,000 kilometers of a defense line constructed by the Germans in the occupied territories.”13 That information was forwarded to the Dutch government-in-exile, which allowed the Allies to accurately bomb German defenses. They also managed to learn the location of a German Vengeance Weapon 1 launch site; the Vengeance Weapon was a type of unmanned flying bomb that the Germans were using to bomb London.14 The information was passed on to the government too, though it’s unclear to me if that helped the Allies disable these bombs.

By this point, other members of the Resistance had begun “liquidating” Nazi officers.15 It sounds like they would literally just shoot someone in public if they happened to spot them. Perhaps unsurprisingly, retaliations would follow these assassinations, and it became too dangerous for Frans—who seemed to be the main assassin doing this—it became too dangerous for Frans to keep assassinating Nazis in public. So he decided to put his Moffen girls to work again.

Truus and Freddie began seducing German SS targets and luring them out to the woods for more privacy, where a member of the resistance would usually do the actual work of killing the soldier. Truus was the first to pick up a guy; Freddie would keep an eye on them, Frans would show up and shoot the officer, then get rid of the body.

Eventually, the girls started killing the officers themselves. They had shooting lessons, then would lure officers into the woods and kill them. Freddie explained, “We only shot real traitors. When you see someone fall, your natural instinct is to pick them up.”16 Still, someone else would go out and bury the bodies, as it seems the girls weren’t physically able to. In case you’re curious, there’s a chance these bodies were never all recovered or returned to Germany after the war; in an interview for VICE, Freddie alluded to that possibility.17

Around the same time, they began receiving more weapons training from a dentist. It sounds like they may have requested it, because being involved in assassinations was really risky. Hannie began carrying a handgun in her purse at all times.18

It wasn’t all assassinations and violence, though. Hannie and Truus were often trusted with escorting young children to safe houses. No one blinked an eye at a young woman and a child crossing the street. Freddie, however, looked so young still that it wasn’t safe for her to do it. She had dark hair, and there was a constant fear that she would be mistaken for a Jewish child herself, which seemed worse when she tried to escort actually Jewish children.

Freddie remained with Truus in safe houses. One was with the Boom family, where the sisters were hidden in a secret room inside a bedroom. On February 28, 1944, the house was raided during a Bible study. 30 people, including the entire Boom family, were arrested and the house was sealed up and put under surveillance. Freddie and Truus were still hidden inside and had to escape over the roofs of buildings at night. Freddie fell through a glass roof during their escape, but fortunately landed on a mattress and wasn’t severely injured.19

I want to be clear that Freddie and the rest weren’t blindly following orders from Frans or other Resistance leaders. At some point, they were given an assignment to kidnap the children of Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the Reich’s Commissioner of the Netherlands. The plot was to trade his children for a few imprisoned Dutch “radicals.”20 Freddie immediately refused to involve children in their resistance. That “just following orders” excuse was one of the big defenses German soldiers frequently used for committing war crimes, so I think it’s important to note that Resistance members were not using hierarchy as an excuse for doing bad things.

It’s also, I think, worth mentioning that they were scared. Freddie had such bad anxiety leading up to a mission that she “would almost eat her handkerchief.”21 I have to wonder if this is a saying in Dutch that doesn’t translate well into English; at least, it’s not something I’m familiar with. Truus wouldn’t be anxious before, but after, she would frequently become overwhelmed and cry for a while.22 I say this because I think people assume everyone who resisted the Nazis was fearless, but they weren’t. They were normal people who were standing up to fascists.

The winter of 1944-45 was tough. Not only was it a harsh winter in general, but there was a general famine in the Netherlands due to the Nazis cutting off their food supply “in retaliation for the exiled Dutch government supporting the Allies.”23 After four years of war, there weren’t enough crops harvested locally to support the population. People were forced to resort to eating tulip bulbs and grass to survive; 4.5 million people were impacted and 20,000 people died.24

Freddie and the rest went hungry with everyone else, but it didn’t slow them down. They kept making plans, and in early 1945, Hannie and Truus tried to blow up a railway bridge to slow down Nazi movements. That first bomb didn’t work, but another railway bomb did, in the Netelbos, and traffic was slowed down for weeks.

While they handled the bombings, Freddie started to find a woman named Madame Cheval [sometimes written Sieval]. According to reports, she was a French Nazi collaborator who was betraying locals to the Nazis. As the planner of the group, it was up to Freddie to find her, and then once she did, it was up to her to figure out how they were going to assassinate her. It was a tough assignment largely because Cheval rarely left her house, and when she did, it was often in the company of her young son. They continued to refuse to hurt a child, so they wouldn’t attack Cheval while her son was with her; they didn’t even want him to see the violence, let alone get caught in the crossfire.

They did attack her once, on March 21, 1945. She was alone, so they shot at her three times on the street. However, Cheval was lucky: She was wearing a huge fur coat at the time, and the bullets had been caught in it.25 What’s strange is that Freddie’s biographer, Sophie Poldermans, just drops this story at this point. It seems like Cheval/Sieval survived. It’s worth noting that the Dutch government released a list of known Nazi collaborators earlier this year and there is no Madame Cheval/Sieval on it.26 I don’t know if that’s because she was French and their list only focused on Dutch collaborators, but it may point to some confusion in the telling of that story.

Their next target was Dicky Wafelbakker, a journalist and English translator; she had betrayed Resistance members to the Nazis. In fact, the Resistance member she betrayed was a member of the Boom family I mentioned earlier, though Dicky was not the reason the house was raided while Freddie was hiding in it. She had also tried to put a betrayal in writing, but her own postman didn’t trust her and had been opening her letters; when he found a list of nine people she was reporting to the Nazis, he pasted it on to the Resistance.27

On April 13, 1945, Dicky Wafelbakker was walking home when Truus rode up on her bike, with Freddie sitting on the back. They walked right up to Dicky, asking if she was in fact Dicky Wafelbakker. When she said yes, Truus shot her point blank and she died instantly.28 Despite several witnesses, they were not caught, and for a long time, officials considered her murder an unsolved mystery. It wasn’t until later in her life that Truus confessed what had happened.

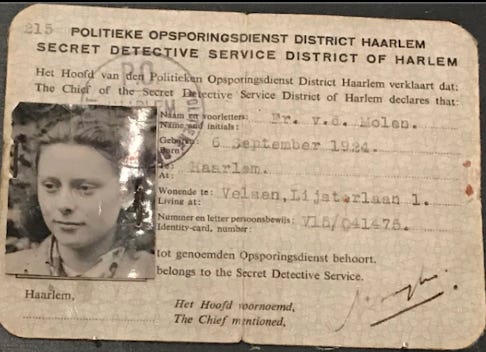

Now, to rewind a little—on the same day as the failed attack on Madame Cheval, March 21, Freddie and Hannie were both stopped by Nazis, though in separate incidents. Hannie was arrested at a routine checkpoint when resistance newspapers were found in her bag. Freddie was stopped at a checkpoint as well, but when she was asked for ID she lied and said “I don’t have one. I haven’t turned 15 yet.”29 She was, in fact, 19 at the time, but she looked young, so the soldiers believed her and allowed her to continue on her way. She realized soon after, however, that Hannie was missing.

After a month of hearing only rumors of Hannie’s arrest, Truus put on a German nurse’s uniform and went to investigate. She managed to convince them that she was a German and wanted to pray with their female prisoners. When she asked after Hannie, she was told that she was “not there anymore.”30 Truus left and fainted out of her fear and anxiety, but they actually still didn’t know that Hannie was already dead at this point. She had been executed on April 17, 1945. After the liberation of the Netherlands in May 1945, Truus and others tried to welcome Hannie home with the other liberated Dutch prisoners, and it was only then that they found out she had been dead for weeks.

After the war, Freddie spent a few months healing at the Loo Palace, which the queen of the Netherlands had opened up to veterans and resistance fighters.31 After that, she worked for the Political Investigation Service, which was responsible for arresting Nazi collaborators. Freddie arrested people all over the country, but started to notice that higher-class and higher-ranking people who had collaborated were left alone; it was only poor people who were being arrested. She reported the discrepancy and was encouraged to ignore it.32 She resigned immediately.

With that, there was no more resistance work to be done. Freddie married an engineer named Jan Dekker; they had three children and lived a pretty quiet life. For years, Freddie disliked discussing her role in the war; we’re not sure how many people she killed or helped kill. When asked this directly, she said, “You shouldn’t ask a soldier that question.”33

For decades, Hannie’s story received the most attention, largely because she had died so tragically close to the end of the war. She had also earned the nickname “The Girl with the Red Hair” during the war, which helped keep her famous after the war. Several movies have been made about her and they all play on that nickname in their titles; one currently in pre-production is simply called The Red Head. Truus also received some acclaim, in part because she became a celebrated sculptor after the war and gained fame that way, as well as through an autobiography she wrote. She talked openly about the impact her role in the Resistance had on her, which shone a light on women in the Resistance.

Both women suffered from depression after the war. At several points in her life, Freddie couldn’t get out of bed for days at a time and Truus spent time in a mental institution.34 Freddie’s son, Remy Dekker, later said that the war didn’t really end for her until she died.

Frustratingly, after the war Truus and Freddie were shunted aside, their heroism dismissed because they were Communists. When other Resistance members were given a resistance pension, Freddie and Truus were both refused it because of their communist leanings; they didn’t end up receiving their pension until well into the 1960s, 20 years after the war ended.35 I doubt there was backpay involved. People believe the orders to ignore the efforts of Communist organizers came from Queen Wilhelmina and Prince Bernhard; even though they were all fighting the Nazis together, they didn’t want people on the political left getting too much credit. Their country was under attack, they were living in exile in London, and they still wanted to be sure they didn’t lose their crowns. It’s such a cynical concern, but it has created room for people to develop a theory that Hannie’s execution was actually the work of royalists in the Netherlands who didn’t like that the political left was gaining popularity because they were so successfully fighting the Nazis. In comparison, the royal family had just turned the country over to the Nazis and fled; I can see why there might have been some political fall out from that. Of course, there’s no hard evidence of this, but I think it’s significant that Truus always believed that it was royalists who executed Hannie, not Nazis.

Regardless of the validity of that, the anti-Communist sentiment in the Netherlands was so strong that the sisters had to go into hiding for years. Policemen surveilled their family homes, and at some point, both women were shot at for being Communists.36 They were ultimately not injured, but very traumatized by it. No one cared about their efforts during the Nazi occupation. Every May, when the anniversary of the liberation of the Netherlands came around, Freddie dreaded it, a feeling that lasted into her old age.37

Nevertheless, Freddie maintained the optimistic fierceness that had defined her young adulthood and fight against the Nazis. She resisted various wars in different forms; in one example that Poldermans gives, she collected sewing machines during the Vietnam War to be shipped or sold to raise money.

Hannie Shaft was given a posthumous award for her work in 1981, which Freddie received on her behalf, but Freddie and Truus received nothing at that award ceremony. This was frustrating enough, but then Queen Beatrix also had to awkwardly approach Freddie and ask for the award back. “I gave you the wrong box,” she explained. “I gave you the big box, which is for the men. The women get the little box.”38 Clearly, in addition to feeling their own snub, they felt very insulted by Hannie’s memory not being memorialized equally to a man’s. Pensions were the same way—male members of the resistance got a larger pension than the women did.39

Finally, on April 15, 2014 (sixty-nine years since the end of the war), Freddie received the Mobilization War Cross from Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, alongside Truus.40 A few months later, each of them had a street named after them in Haarlem. Still, Freddie resisted talking publicly about her experiences. It wasn’t until after her sister died in June 2016 that she began talking openly about her role. She was the last of the trio left.

Freddie Dekker-Oversteegen died on September 5, 2018, one day before her 93rd birthday. Suddenly people gave a damn about her story—after years of living in the shadows, the international press and her country were finally ready to laud the work she had done.

That is the story of Freddie Oversteegen! If you liked this story, you will love my book, Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of. You can let me know your thoughts about this or any other episode on Substack, TikTok and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email at hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it does help other folks discover the show.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Castellanos Clark. Our music is by Danny Wolf of Wolf & Love. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

Until next time, stay unruly.

If you liked this episode, you might like one of these episodes:

Episode 17: Sophie and Hans Scholl

Thanks for subscribing! Your subscription helps fund my research, as well as food and coffee. Not a subscriber yet? Subscribing gets you ad-free episodes right in your inbox, and it supports independent research and publication. Subscribe here.

📚 Bibliography

Atwood, Kathryn J. Women Heroes of World War II: 26 Stories of Espionage, Sabotage, Resistance, and Rescue. Reprint edition. Chicago Review Press, 2013.

De Rooij, Susanne R., Laura S. Bleker, Rebecca C. Painter, Anita C. Ravelli, and Tessa J. Roseboom. “Lessons Learned from 25 Years of Research into Long Term Consequences of Prenatal Exposure to the Dutch Famine 1944–45: The Dutch Famine Birth Cohort.” International Journal of Environmental Health Research 32, no. 7 (July 3, 2022): 1432–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2021.1888894.

Katz, Brigit. “Freddie Oversteegen, Teenage Resistance Fighter Who Assassinated Nazis, Has Died at 92.” Smithsonian Magazine, September 18, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/freddie-oversteegen-who-assassinated-nazis-teenage-resistance-fighter-has-died-92-180970319/.

Poldermans, Sophie. “As Teenagers, These Sisters Resisted the Nazis. Here’s What They Taught Me About Doing the Right Thing.” TIME, August 30, 2019. https://time.com/5661142/dutch-resistance-friendship/.

———. Seducing and Killing Nazis: Hannie, Truus and Freddie: Dutch Resistance Heroines of WWII. Netherlands: AmazonUs/INDPB, 2019.

Roberts, Sam. “Freddie Oversteegen, Gritty Dutch Resistance Fighter, Dies at 92.” The New York Times, September 25, 2018, sec. Obituaries. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/25/obituaries/freddie-oversteegen-dutch-resistance-fighter-dies-at-92.html.

Rossen, Jake. “The Teenage Girl Gang That Seduced and Killed Nazis.” Mental Floss, February 6, 2020. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/578187/teenage-girl-gang-seduced-and-killed-nazis.

Spanjer, Noor. “This 90-Year-Old Lady Seduced and Killed Nazis as a Teenager.” VICE, May 11, 2016. https://www.vice.com/en/article/teenager-nazi-armed-resistance-netherlands-876/.

Treisman, Rachel. “A List of Half a Million Names Shines New Light on Dutch Collaboration with Nazis.” NPR, January 7, 2025, sec. Europe. https://www.npr.org/2025/01/07/nx-s1-5249956/nazi-collaborators-netherlands-archive.

Sophie Poldermans, Seducing and Killing Nazis: Hannie, Truus and Freddie: Dutch Resistance Heroines of WWII (Netherlands: AmazonUs/INDPB, 2019).

Sam Roberts, “Freddie Oversteegen, Gritty Dutch Resistance Fighter, Dies at 92,” The New York Times, September 25, 2018, sec. Obituaries, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/25/obituaries/freddie-oversteegen-dutch-resistance-fighter-dies-at-92.html.

Poldermans, 22

Poldermans, 54

Poldermans, 61

Poldermans, 61

Jake Rossen, “The Teenage Girl Gang That Seduced and Killed Nazis,” Mental Floss, February 6, 2020, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/578187/teenage-girl-gang-seduced-and-killed-nazis.

Poldermans, 75

Poldermans, 75

Poldermans, 76

Poldermans, 76

Poldermans, 76

Poldermans, 77

Poldermans, 77

Poldermans, 78

Poldermans, 79

Noor Spanjer, “This 90-Year-Old Lady Seduced and Killed Nazis as a Teenager,” VICE, May 11, 2016, https://www.vice.com/en/article/teenager-nazi-armed-resistance-netherlands-876/.

Poldermans, 80

Poldermans, 84

Rossen

Poldermans, 121

Poldermans, 121

Susanne R. De Rooij et al., “Lessons Learned from 25 Years of Research into Long Term Consequences of Prenatal Exposure to the Dutch Famine 1944–45: The Dutch Famine Birth Cohort,” International Journal of Environmental Health Research 32, no. 7 (July 3, 2022): 1432–46, https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2021.1888894.

Rooij

Poldermans, 122

“A List of Half a Million Names Shines New Light on Dutch Collaboration with Nazis,” All Things Considered (NPR, January 7, 2025), https://www.npr.org/2025/01/07/nx-s1-5249956/nazi-collaborators-netherlands-archive.

Poldermans, 124

Poldermans, 124

Poldermans, 142

Poldermans, 144

Poldemans, 173

Poldermans, 173

Poldermans, 164

Poldermans, 165

Poldermans, 175

Poldermans, 175

Spanjer

Poldermans, 192

Poldermans, 193

Poldermans, 193

Share this post