Hi everyone,

I can’t believe we’re at the 50th episode now! What a fun few years making these episodes. If you’ve been here since day one, I am so grateful for your support! To celebrate 50 episodes, I’m offering 50% off annual plans for one day only!

This week I’m back with the story of Edythe Eyde, better known in LGBTQ+ circles as Lisa Ben. She single-handedly published the first lesbian magazine in the US, and went on to be a lesbian icon.

🎙️ Transcript

When we dig into the histories of LGBTQ+ folks, we are often met with tales of danger and tragedy. Severed family ties, violence, arrest and persecution. But there was often also hope, humor, and sass. Though sometimes erased in favor of the more “important” history of oppression, happy tales deserve their moment of fame too—and that is what the story of Lisa Ben gives us.

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Castellanos Clark, and today I’m covering the tale of Edythe Eyde, better known as the writer Lisa Ben, who single-handedly created the first lesbian magazine in the US.

Before we jump into this tale of early lesbian zines, I first have to thank all of the paying subscribers on Substack whose patronage helps me make this podcast possible. If you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber over on Substack! When you upgrade, you’ll get access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com

All right, let’s hop into it.

Edythe Eyde was born on February 7, 1921 in San Francisco, California. She grew up in nearby Fremont, the only child of an apricot farmer. Little is known about her early life, though we know she took violin lessons for eight years and developed an interest in fantasy novels.1 Her childhood sounds a bit lonely—in an essay written in her early twenties, she mentions it was “often necessary for me to invent imaginary playmates and invest trees, plants and stones with personalities of their own. I also had animal friends with whom I conversed quite as freely as though they were human beings.”2 Moreover, it seems her parents were a bit repressed and repressive.

When she was fourteen, she fell in love with another girl for the first time. They met in high school—the other girl was fifteen at the time. Eventually the girlfriend left Eyde for another girl at the high school and Eyde was “crestfallen.”3 She confided her sadness in her mother, who asked “You never did anything wrong with her, did you?”4

Eyde, of course, had never thought there was anything wrong with her feelings for the other girl, and so she thought her mom was referring to committing actual crimes. It was the first time it had ever occurred to her that what she was feeling was in any way different from other girls her age. After that, she grew steadily apart from her parents and retreated further into the worlds of fantasy and science fiction.

She borrowed copes of Weird Tales magazine from a boy in the neighborhood. Her parents disapproved of these, as well, which “strengthened rather than lessened my craving for fantasy, for there is quite a bit of psychology that old adage concerning forbidden fruit being the sweetest.”5 She got her hands on other sci-fi and fantasy magazines when she could. When she went off to college and wasn’t under constant supervision, she began reading all the fanzines she could get her hands on, including “Voice of the Imagi-Nation” edited and published by Forrest J. Ackerman. I call it out only because this is one of the few that has been completely digitized, and in it are letters from Eyde.

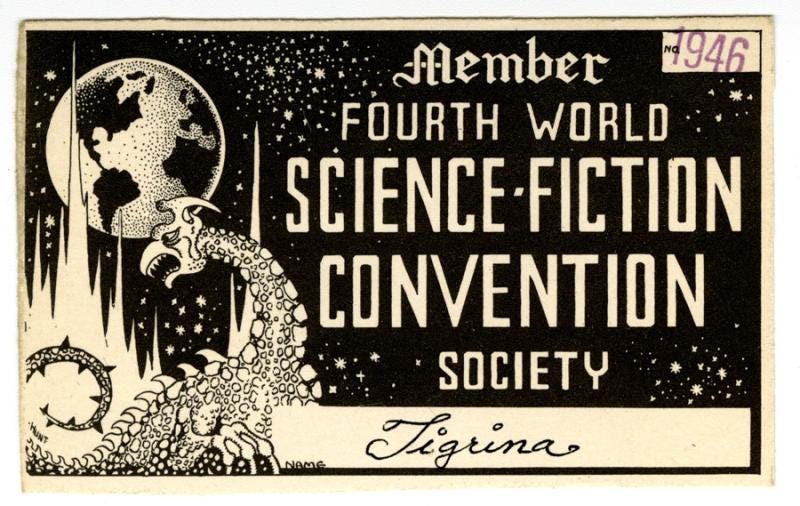

By 1941, she was writing letters to editors and contributing to science fiction and fantasy fanzines under the pseudonym “Tigrina.” In them, she talked not just about her love for sci-fi and fantasy, but also her early interest in the occult and witchcraft. She claimed to be a Satanist and to be practicing witchcraft for revenge on the people in school that bullied her. This created a flurry of responses in the magazine, with a lot of men chiding her for “pretending” to be a Satanist or not having the correct resources to know what being a Satanist meant. It’s all very condescending, and reads like any other misogynistic man trying to put a woman in her place.

In 1942, Eyde complete a 6-month secretarial course and started working in Palo Alto, which allowed her to move out of her parents’ house.6 This was during World War II, which was the first time in the US that unmarried women could easily move out of their parents’ homes. They took the jobs that opened up when men went to war which made the women financially independent. They moved to cities, got jobs, and then even when men returned from war women stayed in the cities and tried to maintain that freedom as much as they could.

In 1945, she moved to Los Angeles to escape the repressive atmosphere of her parents and her hometown. It’s unclear, but it seems like she might not have had much contact with her parents after this time. Despite not knowing anyone there, she made friends fairly easily, it seems.

In the book Making History by Eric Marcus, Eyde talks about how she was so sheltered in Fremont that when she moved to LA she didn’t know the word “lesbian” or that “gay” could mean anything other than happy.7 She met some girls in her building who introduced her to this whole new world. In the documentary Before Stonewall, Eyde was interviewed as Lisa Ben and said about her female neighbors, “They took me into their collective bosoms, so to speak… They took me to a girl’s softball game, and of course I didn’t care anything about softball, but I sure liked watching all the girls running around in their shorts.”8 Soon after that they took her to her first gay bar, If Club, where she danced with other women and was introduced to the gay underground scene of LA.9

Eyde talks about how she never drank at the bars because of the raids from the police. She always wanted to have a clear head, which came in handy when police stopped her inside a club and she gave an unclear fake name. She wasn’t arrested that night or any other, but she was right to do it—these were the days when the names of people arrested for being at gay clubs would get printed in papers the next day under headlines like “Party of Perverts Broken Up.”10 The people listed would often lose their jobs.

She got a job as a secretary at RKO Pictures. Interestingly, her boss didn’t actually have enough work to occupy her all day. He told her she could do whatever she wanted as long as she looked busy when he came by, so in June 1947 she began typing up her own magazine, Vice Versa. The name was a pun by the opinion that the “lesbian lifestyle” was a kind of vice, and she was trying to prove it was the opposite of that.11 It would be five years before another queer-affirming magazine was published in the US.12 In fact, she subtitled the magazine “America’s Gayest Magazine.”13

Vice Versa was completely anonymous. Eyde passed them out for free one-by-one, or mailed them out to people in anonymous envelopes with no return address. She encouraged people to pass the magazine on when they were done, and it gained an estimated readership of over a hundred women, not just in LA but wherever they were mailed. That may not sound like much, but lesbian magazines today average about 1000 subscribers, and they’re allowed to advertise.14

Eyde’s goal though was to get into the hands of other queer women in Los Angeles. She was lonely, and trying to make friends—this seemed like a good way to do that.

Impressively, Eyde typed nearly all of it herself, from essays to book reviews to poetry to movie reviews. In fact, one of her reviews has been archived by the Library of Congress as the best known description of the lost movie Children of Loneliness from 1935.15 Only a few articles ever published in Vice Versa were submitted by other writers.

Now, Eyde’s work had guts. In Making History she humbly downplays it a little bit, but she’s really making big swings here. In the fourth issue of the magazine, she wrote an essay called “Here to Stay.” Here’s an excerpt from it:

Whether the unsympathetic majority approves or not, it looks as though the third sex is here to stay. […] Homosexuality is becoming a less and less taboo subject, and although still considered by the general public as contemptible, or treated with derision, I venture to predict that there will be a time in the future when gay folk will be accepted as part of regular society.

[…]

I believe that the time will come when, say, Stephen Gordon, will step unrestrained from the pages of Radclyffe Hall’s admirable novel, Well of Loneliness, onto the silver screen and, once precedent has been broken by one such motion picture, others will be sure to follow. Perhaps even Vice Versa might be the forerunner of better magazines dedicated to the third sex, which in some future time might take their rightful place on the newsstands beside other publications, to be available openly and without restriction to those who wish to read them.

[…]

In these days of frozen foods, motion picture palaces, compact apartments, modern innovations, and female independence, there is no reason why a woman would have to look to a man for food and shelter in return for raising his children and keeping his house in order unless she really wants to. Never before have circumstances and conditions been so suitable for those of lesbian tendencies.16

This is a bold stance to take in 1947, and everyone who interviewed her commented on it. Many called her prophetic because, well, in a way she was. This future she imagined has largely come to pass. Though, to be fair, we still do not have a good film adaptation of Well of Loneliness.

Now, because being gay was illegal she couldn’t exactly send her magazine out to printers. So, Eyde composed her work at home then produced Vice Versa by printing them on carbon paper on her office typewriter. That allowed her to produce five copies at a time, and then she’d do it again. Each issue had only ten copies—some say 1217, others say 1618—but a lot of early zines had really small “print runs.”

I’m maybe harping on this because I resent that important resources for queer history like JSTOR or the documentary Before Stonewall are still calling ONE the first queer magazine when it wasn’t. Some might point out that ONE was more well-connected: It had contributors from the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, and a Swiss magazined called Der Kreis—is one woman working mostly alone really a magazine? I believe it is. Queer magazines had to operate clandestinely, and sometimes that meant going at it mostly alone. To my view, the main difference between Vice Versa and ONE is that ONE had a commercial bend, it was sold instead of being given out for free.

Importantly for documentation, ONE was the center of a big FBI sting in 1952; despite using pseudonyms, the writers and editors were named and the FBI called their employers, trying to get them all fired.19 In 1953, distribution of ONE was held up by the post office until someone in Washington demanded that the magazines be released.20

This often happens in history—things that are sold or involved criminal activity require more documentation. They require ledgers, police reports, the type of documentation that survives. Since they’re documented in regularly-checked archives, they get noticed by historians. ONE is surely the earliest US queer magazine that the FBI flagged, but just because Edythe Eyde wasn’t caught doesn’t erase the value of her work.

And to be clear, she nearly was caught. Though she didn’t put a return address on her mailed envelopes, she wasn’t secretive about what she was doing. I mean, she typed the magazine up at work—she only wasn’t caught because her boss was away a lot! She admits in Making History that she was naïve, and didn’t realize that not putting smut in her magazine wasn’t enough to qualify as “not obscene.” She didn’t understand that the very nature of the magazine made it “obscene” and that she could be criminally punished for that. At some point, a friend called her up and warned her to stop putting the magazine in the mail because of obscenity laws. The US Postal Service was efficient at catching this stuff, because they had an enforcement arm that had been around longer than any other branch of the federal police.21 Being caught could ruin your life.22 So she decided to stop mailing it out from the office, but Edythe Eyde kept mailing out Vice Versa.

It was doomed to be a short-lasting publication, however. After nine issues had come out, RKO Pictures was being sold off piece-meal; Eyde was laid off in February or March 1948.23 At her next job, she didn’t have the privacy and time that she’d had at her first job—instead of working for one man in a private office, she was part of a larger typing pool where everyone could see what you were up to.24 Eyde also didn’t own a typewriter of her own, so she couldn’t type it up at home either. She was forced to give up making Vice Versa; the final issue had come out in February 1948.

Of course, Eyde could have bought a typewriter and chose not to. As Rodger Streitmatter points out in his article about her work,

Overarching these logistical impediments was the fact that the young woman had accomplished her goal. Ben, with a coy smile, recently recalled: "I was getting a little social life, too, becoming a sly little minx. I was discovering what the lesbian lifestyle was all about, and I wanted to live it rather than write about it.”25

When the Daughters of Bilitis formed in 1955, Eyde joined their LA chapter as soon as she could. When the activist group started publishing their magazine about queer life, The Ladder, Eyde contributed. Things were still illegal, so writers and editors were still using pseudonyms. Eyde initially signed her name as Ima Spinster, but her jokey name was firmly rejected by the editors.26 Instead, Lisa Ben was born. The name, of course, is an anagram for lesbian.

In between the two magazines, Eyde began doing queer parodies/covers of popular music. One of her most popular covers was “The Girl That I Marry,” based on, well, “The Girl That I Marry” from the musical Annie Get Your Gun!—I’ve included it in the Substack, if you’d like to check it out.

Fortunately, it seems like several recordings survive. This is so lucky because Eyde didn’t really set out to have a music career by any means. She wrote and sang these more in a reaction to what she saw as gay entertainers selling out the community for a buck. In Making History, she recounts the time she was at a gay bar, The Flamingo, and saw a gay comedian take the stage to make a dirty and offensive joke about Beverly Shaw, a popular lesbian singer at the time.27 It infuriated her, so she decided to make positive entertainment about women who loved women. To her surprise, her songs were a hit.

In the Before Stonewall documentary, her music is really all that’s brought up—she sings a few songs in the film. The documentary doesn’t mention Vice Versa at all, naming ONE the first LGBTQ+ magazine in the US, which makes me wonder if they had no idea what Lisa Ben/Edythe Eyde had been up to in 1947. I watched the documentary twice wondering if I’d missed the part where they talk about her contributions to lesbian magazins, but nope. It’s just…not there.

Anyway. In 1960, Daughters of Bilitis released a 45 rpm record of two of her songs: “Cruising Down the Boulevard” and “Frankie & Johnnie.” These records are so rare—I’m not sure how much they’re worth, but if you find one laying about in an attic, don’t throw it out.

It seems that after the 1960s she mostly retired from public life. She did appear in the 1984 documentary I’ve mentioned a few times. She also was interviewed by Eric Marcus for his 1992 book Making History; the audio recordings of those interviews were later turned into a podcast, which is really cool.

Instead, she adopted some cats and continued working as a secretary. She eventually was able to buy a house in Burbank, California all on her own.

Throughout her life, Eyde maintained her love of science fiction. She joined the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society nearly as soon as she moved to LA. She served as the secretary of the group, often signing minutes she took of meetings with her trademark Tigrina moniker. But in at least one vote, she nearly became the leader of the society.28

In 2002, she mentioned in a letter to J.D. Doyle of Queer Music Heritage that she was shaken after a photo of her and her home address were circulated to newsletters after she was spotted at a LGBTQ festival in 2001; “I have gone into seclusion and no longer desire any publicity.”29 Nevertheless, she provided with Doyle a poem and some song lyrics.

In 2010, Eyde was inducted in the Association of LGBTQ+ Journalists’s Hall of Fame. Though her name and her pseudonyms Lisa Ben and Tigrina were not always linked with her—a status she preferred to protect her privacy—since the late 1980s she’s been steadily being recognized for her contributions to lesbian culture.

Eyde never married. She maintained her love for touches of the occult—it’s said she has 13 cats living with her when she had to sell her house to move into assisted living. She died on December 22, 2015 at the age of 94.

Before I end this, I want to close with Eyde’s statement on the front page of the first issue of Vice Versa, where she declared why she was risking her job and place in society to write this magazine:

There is one kind of publication which would, I am sure, have a great appeal to a definite group. Such a publication has never appeared on the stands. News stands carrying the crudest kind of magazines or pictorial pamphlets appealing to the vulgar would find themselves severely censured were they to display this other type of publication. Why? Because Society decrees it thus.

Hence the appearance of VICE VERSA, a magazine dedicated, in all seriousness, to those of us who will never quite be able to adapt ourselves to the iron-bound rules of Convention.30

That is the story of Edythe Eyde! If you liked this story, you will love my book, Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of. You can let me know your thoughts about this or any other episode on Substack, TikTok and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email at hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it does help other folks discover the show.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Castellanos Clark. Our music is by Danny Wolf of Wolf & Love. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

Until next time, stay unruly.

If you liked this episode, you might like one of these episodes:

Bonus Episode: The Lavender Scare

It began, as these things often do, with someone trumping up scary stories to sell newspapers.

Okay, that’s being a little glib, but the point stands that the Lavender Scare began as part of a larger panic about sex crimes.

📚 Bibliography

Before Stonewall. Documentary, 1984. https://tubitv.com/movies/677407/before-stonewall.

Brandt, Kate. Happy Endings: Lesbian Writers Talk about Their Lives and Work. tallahasee, florida: Naiad Press, 1993. https://archive.org/details/happyendingslesb00bran/page/130/mode/2up?view=theater.

———. “Lisa Ben: A Lesbian Pioneer.” Visibilities, no. Jan/Feb 1990 (January 1990). https://queermusicheritage.com/viceversa0.html.

Eyde, Edythe. “Here to Stay.” Vice Versa, September 1947. Queer Music Heritage. https://queermusicheritage.com/viceversa4.html.

———. “In Explanation.” Vice Versa, June 1947. Queer Music Heritage.

———. Letter to J.D. Doyle. “Lisa Ben Correspondence,” August 9, 2002. Queer Music Heritage. https://queermusicheritage.com/viceversa1b.html.

Eyde, Edythe “Tigrina.” “Why I Prefer Weird Fantasy.” Pacificon Combozine, 1946.

Gormly, Kellie B. “Who Was ‘Lisa Ben,’ the Woman Behind the U.S.’s First Lesbian Magazine?” Smithsonian Magazine, June 26, 2024. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-was-lisa-ben-the-woman-behind-the-uss-first-lesbian-magazine-180984596/.

Halley, Catherine. “Julie Enszer: ‘We Couldn’t Get Them Printed,’ So We Learned to Print Them Ourselves.” JSTOR Daily, June 19, 2020. https://daily.jstor.org/julie-enszer-we-couldnt-get-them-printed-so-we-learned-to-print-them-ourselves/.

———. “ONE: The First Gay Magazine in the United States.” Archive. JSTOR Daily (blog), July 15, 2020. https://daily.jstor.org/one-the-first-gay-magazine-in-the-united-states/.

“Lisa Ben.” In Wikipedia, September 24, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Lisa_Ben&oldid=1247577991.

“Lisa Ben Papers Now Available to Researchers | One Archives.” Accessed January 28, 2025. https://one.usc.edu/news/lisa-ben-papers-now-available-researchers.

Litterer, Kate. “Lisa Ben, Lesbian: Queering Rhetorical Circulation.” One Institute: From the Reading Room (blog), 2018. https://www.oneinstitute.org/lisa-ben-lesbian/.

Lopez, German. “The Homophobic History of the Post Office.” Vox, May 28, 2014. https://www.vox.com/2014/5/28/5756494/the-homophobic-history-of-the-post-office.

Marcus, Eric. Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990. Kindle Reprint Edition. Harper Voyager Impulse, 2018. https://bookshop.org/a/79066/9780062848260.

Marcus, Eric, and Edythe Eyde. Edythe Eyde. Making Gay History, 2016. https://makinggayhistory.org/podcast/episode-1-3/.

———. Edythe Eyde’s Gay Gal’s Mixtape. Making Gay History, 2017. https://makinggayhistory.org/podcast/bonus-episode-edythe-eydes-gay-gals-mixtape/.

Meeker, Martin. “Behind the Mask of Respectability: Reconsidering the Mattachine Society and Male Homophile Practice, 1950s and 1960s.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 10, no. 1 (2001): 78–116.

O’Dell, Cary. “Gay Cinema/Lost Cinema: ‘Children of Loneliness’ (1935).” Webpage. The Library of Congress: Now See Hear! (blog), November 17, 2015. https://blogs.loc.gov/now-see-hear/2015/11/a-movie-missing-in-action-children-of-loneliness-1935.

Postal Facts. “Postal Facts - U.S. Postal Service.” Accessed January 28, 2025. https://facts.usps.com/

Smithsonian Music. “Lisa Ben ‘Cruising Down the Boulevard / Frankie & Johnnie’ 45rpm Single,” May 31, 2020. https://music.si.edu/object-day/lisa-ben-cruising-down-boulevard-frankie-johnnie-45rpm-single.

Streitmatter, Rodger. “Vice Versa: America’s First Lesbian Magazine.” American Periodicals 8 (1998): 78–95.

“TIGRINA (1940s).” Accessed January 27, 2025. https://www.fiawol.org.uk/fanstuff/THEN%20Archive/LASFS/Tigrina.htm.

“Vice Versa, Introduction.” Accessed January 28, 2025. https://queermusicheritage.com/viceversa0.html.

FYI, some of the links in here are affiliate links!

Streitmatter, Rodger. “Vice Versa: America’s First Lesbian Magazine.” American Periodicals 8 (1998): 78–95.

Eyde, Edythe “Tigrina.” “Why I Prefer Weird Fantasy.” Pacificon Combozine, 1946.

Marcus, Eric. Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990. Kindle Reprint Edition. Harper Voyager Impulse, 2018.

Marcus, “Gay Gal”

Eyde, “Why I Prefer Weird Fantasy”

Streitmatter, 79

Marcus, “Gay Gal”

Before Stonewall. Documentary, 1984. https://tubitv.com/movies/677407/before-stonewall.

Marcus, “Gay Gal”

Marcus, “Gay Gal”

Marcus, “Gay Gal”

Halley, Catherine. “ONE: The First Gay Magazine in the United States.” Archive. JSTOR Daily (blog), July 15, 2020. https://daily.jstor.org/one-the-first-gay-magazine-in-the-united-states/.

Brandt, Kate. “Lisa Ben: A Lesbian Pioneer.” Visibilities, no. Jan/Feb 1990 (January 1990). https://queermusicheritage.com/viceversa0.html.

Halley, Catherine. “Julie Enszer: ‘We Couldn’t Get Them Printed,’ So We Learned to Print Them Ourselves.” JSTOR Daily, June 19, 2020. https://daily.jstor.org/julie-enszer-we-couldnt-get-them-printed-so-we-learned-to-print-them-ourselves/.

O’Dell, Cary. “Gay Cinema/Lost Cinema: ‘Children of Loneliness’ (1935).” Webpage. The Library of Congress: Now See Hear! (blog), November 17, 2015. https://blogs.loc.gov/now-see-hear/2015/11/a-movie-missing-in-action-children-of-loneliness-1935.

Eyde, Edythe. “Here to Stay.” Vice Versa, September 1947. Queer Music Heritage. https://queermusicheritage.com/viceversa4.html.

Gormly, Kellie B. “Who Was ‘Lisa Ben,’ the Woman Behind the U.S.’s First Lesbian Magazine?” Smithsonian Magazine, June 26, 2024. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-was-lisa-ben-the-woman-behind-the-uss-first-lesbian-magazine-180984596/.

Brandt, Kate. Happy Endings: Lesbian Writers Talk about Their Lives and Work. Tallahasee, Florida: Naiad Press, 1993. https://archive.org/details/happyendingslesb00bran/page/130/mode/2up?view=theater.

Halley “ONE: The First Gay Magazine”

Halley “ONE: The First Gay Magazine”

Postal Facts. “Postal Facts - U.S. Postal Service.” Accessed January 28, 2025. https://facts.usps.com

Lopez, German. “The Homophobic History of the Post Office.” Vox, May 28, 2014. https://www.vox.com/2014/5/28/5756494/the-homophobic-history-of-the-post-office.

Marcus, “Gay Gal”

Gormly, “Who Was ‘Lisa Ben’”

Streitmatter, 82

Marcus, “Gay Gal”

Marcus, “Gay Gal”

Litterer, Kate. “Lisa Ben, Lesbian: Queering Rhetorical Circulation.” One Institute: From the Reading Room (blog), 2018. https://www.oneinstitute.org/lisa-ben-lesbian/.

Eyde, Edythe. Letter to J.D. Doyle. “Lisa Ben Correspondence,” August 9, 2002. Queer Music Heritage. https://queermusicheritage.com/viceversa1b.html.

Eyde, Edythe. “In Explanation.” Vice Versa, June 1947. Queer Music Heritage.

Share this post