Hi everyone,

Welcome back to the podcast! I know it’s been a while since I published an episode, but I’m hoping I’m back for good. Things have slowed down for me for a little while, so I can focus on this more. And I’m excited—I’ve really missed making this show!

🎙️ Transcript

Our intro today is a little different because I have to gush about how excited I am to be covering Harriet Bell Hayden. As you’ll see, hers is exactly the kind of story that gets left out of traditional histories and is finally being resurrected. Until 10 months ago (March 2024 or so) no one paid much attention to Mrs. Hayden, preferring to look to her more famous husband, Lewis, when talking about Boston’s abolitionist movement. And then the Boston Athenæum presented an exhibition of her photo albums, curated by Dr. Makeda Best and Dr. Virginia Reynolds Badgett. The result was a small public resurgence in interest Harriet’s life, and a better understanding of women’s roles in the abolitionist movement. Just like Coretta Scott King never gets enough credit for how she supported her husband Martin Luther King, Jr., Harriet Bell Hayden has been denied her fair due for nearly 150 years.

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Castellanos Clark, and today I’m covering the tale of Harriet Bell Hayden, a woman who was born into slavery, escaped, and became one of Boston’s strongest abolitionists.

Before we jump into this tale of the abolitionist movement, I first have to thank all of the paying subscribers on Substack whose patronage helps me make this podcast possible. If you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber over on Substack! When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com

All right, let’s hop into it.

Historians are pretty sure that Harriet Bell was born between 1813 and 1816 in Kentucky. We don’t have a firm date because she was born enslaved and enslavers didn’t keep the most efficient records and many records that were kept were lost during the Civil War. Her enslaver was a man named Patterson Bain, and as she grew up she became a maid and handled housework and childcare for the Bain family. Unfortunately, we really don’t have a lot of other information about her childhood. We know that around 1839 she had a son named Joseph, but it is unclear who the boy’s father was.

Documentation of her story really begins in 1840, when Harriet met Lewis Hayden in Lexington. The two fell in love and though they couldn’t live together, they got married in 1842. Many sources make a point of saying that Lewis treated her son Joseph as if he were his own.

Despite their happiness, the spectre of being sold and separated haunted them: Lewis had already lost his mother, his brothers, his first wife, and his own child through the auction block.1 He never knew what became of any of them and he didn’t want the same to happen with Harriet and Joseph.

Probably both of them had thought of attempting escape before. But it was the love of their family and the hope of staying together that pushed them to start planning.

In 1844, when Lewis was 33, he was leased to the owners of the Phoenix Hotel in Lexington, Kentucky.2 While working there, he met Delia Webster, who introduced him to her friend Calvin Fairbank. Webster was a schoolteacher and Fairbank a ministry student. They also were both working to help enslaved people escape north.

On the evening of Saturday September 28, 1844, Lewis helped Harriet and Joseph steal away from their enslaver’s house.3 In the dark night, they met Webster, Fairbank, and their driver Israel. Perhaps ironically, Israel was an enslaved man who had been hired out to Fairbank with the hackney he had rented.4 Taking back roads and moving as inconspicuously as possible, the group made their way north and finally crossed into Ohio, a free state. At the border, Webster and Fairbank turned around in the hired hackney and left Harriet, Joseph, and Lewis to make their way to Sandusky, Ohio alone.5 With luck, Webster or Fairbank would have been able to send ahead word of their approach so they would be greeted by someone who wouldn’t turn them into the armed and vicious slave catchers that roamed the border states.

This was what traveling the Underground Railroad was like. It wasn’t a literal railroad so much as a series of safe houses that people traveled between under cover of darkness. Getting just to a free state was not always enough—the ultimate safety for escapees was leaving the country. People made for the Caribbean, if they were in the far south but more often Canada if they were further north. Canada was where the Haydens were running to.

But even as they dodged slave catchers and made their way north, they received news that Webster, Fairbank, and Israel had been caught returning to Lexington. Israel was tortured until he revealed their route; Fairbank and Webster were arrested sentenced to prison for their roles in aiding Harriet and Lewis in their escape.

The Haydens hurried north, just ahead of their pursuers. After they crossed the border, they remained there for six months, but it wasn’t long before they felt drawn to return to the US and help end slavery.6 They moved first to Detroit, then to “the epicenter of the abolitionist movement and home to one of the nation’s most dynamic free Black communities: Boston, Massachusetts.”7 They arrived in 1845, and eventually moved into a house at 9 Southac Street (now 66 Phillips Street) in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood in 1848. Lewis became a tailor and the couple opened a clothing store on the ground floor of their home, as well as turning the upper floors into a boarding house.8 Around the same time they returned to the US Harriet gave birth to their daughter, Elizabeth.9

Naturally, they had not forgotten the people who helped them escape Kentucky. Delia Webster had already left prison, but Lewis wrote to his former enslaver, working out a buyout in order to get Calvin Fairbank released from prison. Using their new contacts in Boston, they were able to raise the necessary $650 quickly and Fairbank was released.10 (For context, $650 in 1846 is worth over $26,000 today.11)

I’ve been saying “they” but this is where I want to refocus on Harriet. Like any form of activism, there’s a bit of networking that goes into becoming a member of a movement. And it seems like this is where Harriet really shined. While Lewis became involved in politics—he eventually was elected to the Massachusetts Legislature in 1872—it seems like Harriet was good at the social aspect of abolition. I imagine when they arrived in Boston, she did a lot of the daily visiting with members of the abolitionist movement that would have been required to build their trust. While the movement was largely decentralized, the Underground Railroad also wasn’t just a listserv you signed up for. To become a conductor or a stationmaster, people had to trust you before they would send freedom seekers your way.

Harriet made her house into a station on the Underground Railroad, and she and her family were seen as stationmasters. They weren’t personally escorting folks out of the south, but they were responsible for hiding them and caring for them on their way to Canada. People might stay for only a few hours or for several days, and Harriet was who kept them fed, gave them new clothes if they needed them, and kept them cheered up before helping them continue on. They reportedly built a secret tunnel in or under their home to help with this, though I only saw that in one source.12

While already a risky business, it became more risky in 1850, when the Fugitive Slave Law was passed. Not only did the new legislation make it easier for slavecatchers to operate in free states to recapture escaped slaves—and sometimes capture innocent free Black people—but it also required that everyone participate in recapturing escapees. Anyone caught helping someone escape enslavement could be fined up to $1,000 per person, which is over $40,000 today.13 To make it worse, Lewis was considered freed—he had bought his freedom at the same time that he helped Fairbanks get out of prison—but Harriet and Joseph were still considered fugitives. They technically remained fugitives until the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863.

Harriet could have quailed in the face of this threat. She could have said that bringing other escapees into her home was too risky when not only could she be fined for every fugitive she helped but she herself could be forced back to Kentucky. But she didn’t. She became even more dedicated to helping people escape slavery.

For example: On February 15, 1851, her husband led a group of twenty abolitionists to the Boston Courthouse to free Shadrach Minkins, a freedom seeker who had been arrested by slavecatchers. Harriet was probably one of the people who housed and kept Minkins safe until he could be spirited away to Canada.14 While this daring escape was celebrated by abolitionists and no one was arrested for freeing Minkins, it was considered “strictly speaking… treason.”15 Nevertheless, Harriet continued opening their home to other people escaping slavery.

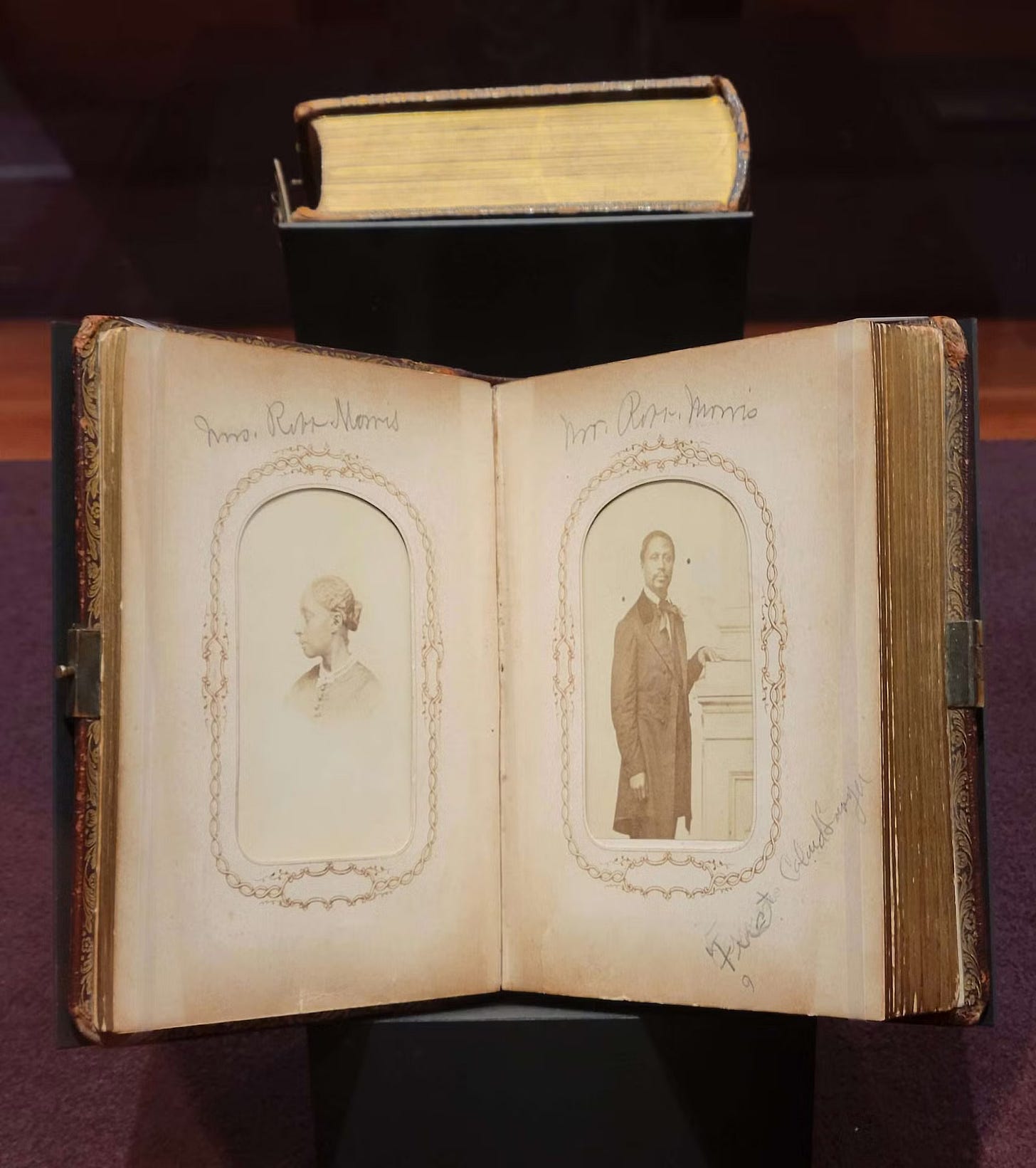

And not only to people escaping slavery—Harriet’s home became a meeting spot for now-famous leaders of the Underground Railroad. Boston’s prominent Black abolitionist figures including suffragist Virginia Hewlett Douglass, lawyer Robert Morris, abolitionist and author Harriet Beecher Stowe, educator Elizabeth N. Smith, Dr. John V. DeGrasse, and Dr. Samuel Birmingham, among many others, all visited her for social calls and to discuss business.16 The home was considered quite safe, and journalist Pauline Hopkins recalled in 1901 that on any given evening, anyone entering the house would have “found the table surrounded by men engaged in earnest study, one hand holding the spelling-book or writing in the copybook, the other resting on pistol or knife ready to sieze them if necessary.”17

We know because she collected photographs of them into two albums that were preserved and passed onto the Boston Athenæum after she died. These little photographs, called carte de visites, were calling cards with photographs of the visitor on them, meant to be dropped off at someone’s home. They were popular in the US in the second half of the 19th century, though they were really only available to people who had the money to pay for a portrait of themselves. Harriet collected 87 of these photographs in her albums, and they give us a wonderful insight into the network of the abolitionist movement in Boston. As someone writing for the Boston Athenæum points out, “These photographs were more than keepsakes—they were a form of activism for the Black community. Using refined clothing and poses, they took control of their image and challenged stereotypes.”18

If you’re interested in seeing the photos, they’ve all been digitized and are available online through Boston Athenæum’s Digital Collections. I’ve included a link in the Substack.

It was these photos that got me interested in Harriet’s story. As I mentioned at the top, her husband Lewis has been better remembered by history for being one of the first Black men ever elected to a state legislature, but these photos remind us tha tabolition was a social mission, not just a political one. Though Massachusetts was a free state, the work of the Haydens and many other people involved in saving enslaved people was still illegal, and as such had to happen behind closed doors. Women like Harriet did a lot of the work of bringing other activists together and that work is often cruelly forgotten.

I watched a recent reenactment of Lewis Hayden’s meeting to convince people to free Shadrach Minkins and it only showed men talking. But it showed the men sitting in a drawing room, drinking tea and eating food while they discussed. And I wanted to scream because a woman prepared that tea and that food. If it was set in Lewis Hayden’s drawing room then Harriet Hayden prepared that food. She probably also set the time for everyone to meet, ensured there were enough chairs, made sure that they were safe. She probably had input into what to do with Minkins once he was out of the courthouse. But she’s nowhere in the story, and she deserves to be.

Especially because of the danger involved in having these people in her home. Abolitionists became well-known to slavecatchers, and suspected conductors and stationmasters were surveilled, much like the police surveil anyone connected with criminals today. Harriet’s home was watched closely and often approached by slavecatchers. When she answered the door on a slavecatcher’s face, her response to them was always to warn them that they kept gunpowder in the house. Both she and Lewis threatened slavecatchers regularly, telling them that they would rather blow up the house and kill everyone inside than hand over anyone to be taken back to the south and re-enslaved.

Harriet and Lewis both developed such a fearsome reputation with pro-slavery people that when they were suspected of harboring William and Ellen Crafts, the Boston marshal declined to help slavecatchers enter the home to see if the Crafts were there. “No money will induce me to try to make an arrest from [the Hayden home],” he reportedly said.19

Their house on Southac became known as the Temple of Refuge, the most important stop on the Underground Railroad in Boston. While documentation was necessarily scant, it’s estimated that Harriet housed hundreds of people escaping slavery.20 And she did it all while facing not just great personal risk but also great personal tragedy—sometime before 1860, her daughter Elizabeth died. She was last recorded as a five-year-old in the 1850 census, then disappears from public record. Though her son Joseph was still alive, it must have been difficult for Harriet and Lewis to face this loss while also dealing with such stressful situations.

In 1859, Harriet hosted John Brown while he was planning for his raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia that same year. Though Lewis was repsonsible for finding men to help Brown and financial backers for the raid, an obituary for Harriet hints at her key role in planning it: "no woman perhaps knew more than she of the inside history of the Harper’s Ferry tragedy."21 Unfortunately, what exactly she knew and what exactly she contributed seem lost to history, at least for now.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Joseph went off to war. He enlisted in the US Navy, and died of disease in Alabama in June 1865, just as the final Confederate troops were finally surrendering.22 While her emotional reaction to this loss doesn’t seem to be recording—in fact, Joseph rarely comes up in her story at all—I can’t imagine the pain she must have felt knowing her son died back in the South just as the war ended.

During the war, Harriet finally had a chance to learn to read and write.23 After the war, she was able to use these new skills to further her other goals. At some point, she joined the West End Women’s Suffrage group and campaigned for the temperance movement.24 In 1875, she co-founded the Prince Hall Auxiliary Association to provide an organizing space for female family members of the Prince Hall Masons, a Black masonic society, then led the group’s fundraisers for a new masonic lodge in the city.25 The next year, she—seemingly single-handedly—organized a celebration for Black Bostonians for the centennial of the American Revolution. It’s here that we see the clearest acknowledgment from her husband of her work: Lewis’s address at the event praised Black women of Boston and called for equal rights, saying, "the men of Massachusetts owe a debt to you, for, as of yet, they have not recognized your rights… there should be [no rest] until every human being is made equal before the law.”26

What she was up to after 1875 is less clear. She was in her 60s by then, so hopefully she was able to rest, though we do know that she never gave up on advocating for Black Americans.

Lewis died in April 1889. Harriet lived another four and a half years, dying in their home on Southac Street on December 24, 1893. When she died, she left all of hers and Lewis’s possession to the medical school at Harvard, establishing a scholarship for Black medical students that is still awarded today.27 In her obituary, her friends wrote,

Mrs. Hayden was of an heroic mould, and no plan for the deliverance of the slave from chains could be too dangerous for her sanction and active support. When her husband, overwhelmed with the danger and magnitude of an undertaking, would waver, her strong, brave, eloquent words would again fire his indignation and arouse his enthusiasm for the work to which they had dedicated themselves. Her bright, cheerful spirit and quaint, original utternaces were an unfailing source of comfort and cheer in the darkest hours of the struggle. No history of that time will be complete without the name of Harriet Hayden and a record of the vigorous part she played.28

That is the story of Harriet Bell Hayden! If you liked this story, you will love my book, Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of. You can let me know your thoughts about this or any other episode on Substack, TikTok and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email at hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it does help other folks discover the show.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Castellanos Clark. Our music is by Danny Wolf of Wolf & Love. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

Until next time, stay unruly.

If you like this episode, you may enjoy the story of Rosa Parks!

Episode 4: Rosa Parks, Part 1

Thanks for subscribing! Your subscription helps fund my research, as well as food and coffee. Not a subscriber yet? Subscribing gets you ad-free episodes right in your inbox, and it supports independent research and publication. Subscribe here.

📚 Bibliography

Best, Makeda. “Public Exhibition Opening: The Harriet Hayden Albums: Framing Freedom.” Presented at the Framing Freedom: The Harriet Hayden Albums, Boston Athenaeum, 10 1/2 Beacon Street, Boston, MA 02108, March 19, 2024. https://events.bostonathenaeum.org/jQ/g/H5QRRnd8mB/public-exhibition-opening-the-harriet-hayden-albums-framing-freedom-4a2KUml9kb/overview.

Boston Athenaeum. “Framing Freedom: The Harriet Hayden Albums.” Accessed February 4, 2025. https://bostonathenaeum.org/whats-on/exhibitions/harriet-hayden-albums/.

Boston.gov. “Boston’s Own Underground Railroad Conductors: Harriet and Lewis Hayden,” February 1, 2020. https://www.boston.gov/news/bostons-own-underground-railroad-conductors-harriet-and-lewis-hayden.

Editors, History com. “Underground Railroad ‑ Definition, Background & Leaders.” HISTORY, October 29, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/underground-railroad.

“Fighting for Freedom: Lewis Hayden and the Underground Railroad.” NPS Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program, November 21, 2018. https://www.y outube.com/watch?v=Xuk0obth4Qs.

Fine Books Magazine. “First Major Exhibition of the Harriet Hayden Albums Displays Original Photos of Notable Black Bostonian and National Abolitionists.” March 18, 2024. https://www.finebooksmagazine.com/fine-books-news/first-major-exhibition-harriet-hayden-albums-displays-original-photos-notable-black.

Greenspan. “6 Strategies Harriet Tubman and Others Used to Escape Along the Underground Railroad.” HISTORY, June 26, 2023. https://www.history.com/news/underground-railroad-harriet-tubman-strategies.

“Harriet Bell Hayden.” In Wikipedia. Accessed February 4, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harriet_Bell_Hayden.

HISTORY. “John Brown’s Harpers Ferry,” August 21, 2023. https://www.history.com/topics/slavery/harpers-ferry.

Hopkins, Pauline E. “April 1901: ‘Famous Men of the Negro Race: Lewis Hayden.’” In The Colored American Magazine Volumes 1-2 1900-1901. New York, NY: Negro Universities Press, 1969. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044014161590?urlappend=%3Bseq=857%3Bownerid=27021597765509495-891.

In 2013 Dollars. “$1,000 in 1850 → 2025 | Inflation Calculator.” Accessed February 4, 2025. https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1850?amount=1000.

In 2013 Dollars. “$650 in 1846 → 2025 | Inflation Calculator.” Accessed February 4, 2025. https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1848?amount=650.

“In Memoriam.” The Woman’s Journal 24, no. 52 (December 30, 1893): 413.

“Lewis Hayden.” In Wikipedia, December 15, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Lewis_Hayden&oldid=1263177837.

Gibson, Lydialyle. “The Picture of Freedom.” Harvard Magazine, May 1, 2024, sec. Arts & Culture. https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2024/05/the-picture-of-freedom.

Holmes, Marian Smith. “The Great Escape From Slavery of Ellen and William Craft.” Smithsonian Magazine, June 16, 2010. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-escape-from-slavery-of-ellen-and-william-craft-497960/.

NPS. “Harriet Hayden.” National Park Service, January 16, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/people/harriet-hayden.htm.

———. “Lewis and Harriet Hayden House.” Boston African American National Historic Site Massachusetts, December 13, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/boaf/learn/historyculture/lewis-and-harriet-hayden-house.htm.

Osho-Williams, Olatunji. “The Remarkable Life of One of Boston’s Most Fervent and Daring Abolitionists.” Smithsonian Magazine, January 2025. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/remarkable-life-one-bostons-most-fervent-daring-abolitionists-180985634/.

Powell, Alvin. “Legacy of Resolve.” Harvard Gazette, February 23, 2015, sec. Arts & Culture. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2015/02/legacy-of-resolve/.

The Cambridge Chronicle. “A Slave’s Gift.” May 26, 1894. https://cambridge.dlconsulting.com/?a=d&d=Chronicle18940526-01.2.101&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN------- .

Tyson, Theo. “The Harriet Hayden Albums.” Boston Athenæum Digital Collections, February 6, 2020. https://cdm.bostonathenaeum.org/digital/collection/p16057coll52.

Wolfe, Brendan. “Shadrach Minkins (d. 1875).” In Encyclopedia Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: Virginia Humanities, December 7, 2020. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/minkins-shadrach-d-1875/.

“Lewis Hayden.” Wikipedia.

“Fighting for Freedom: Lewis Hayden and the Underground Railroad.” NPS Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program, November 21, 2018.

“Fighting for Freedom”

“Fighting for Freedom”

“Fighting for Freedom”

“Fighting for Freedom”

“Fighting for Freedom”

NPS, “Lewis and Harriet Hayden House.”

NPS, “Harriet Hayden.”

“A Slave’s Gift.” The Cambridge Chronicle.

“$650 in 1848 → 2025 | Inflation Calculator.”

Osho-Williams, “The Remarkable Life of One of Boston’s Most Fervent and Daring Abolitionists.”

“$1,000 in 1850 → 2025 | Inflation Calculator.” Accessed February 4, 2025.

Wolfe, Brendan. “Shadrach Minkins (d. 1875).” In Encyclopedia Virginia. Charlottesville, VA: Virginia Humanities, December 7, 2020.

Wolfe

Best, “Public Exhibition Opening: The Harriet Hayden Albums: Framing Freedom.”

Hopkins, “April 1901: ‘Famous Men of the Negro Race: Lewis Hayden.’”

“Framing Freedom.” Boston Athenæum.

Hopkins

Osho-Williams

“In Memoriam.” The Woman’s Journal.

“Harriet Bell Hayden.” Wikipedia.

NPS, “Harriet Hayden.”

NPS, “Harriet Hayden.”

NPS, “Harriet Hayden.”

NPS, “Harriet Hayden.”

Powell, “Legacy of Resolve.”

“In Memoriam.“ The Woman’s Journal.

Share this post