Hi everyone,

Thank you for all the supportive messages I received when I decided to take a short break earlier this month. I was just feeling so burnt out! The break gave me some space to catch up on sleep, think about my priorities, and figure out what comes next, which I really needed.

Anyway, I’m very excited to share this episode about Welsh hero Owain Glyndŵr! I didn't know much about Welsh history when I first started researching this episode back in October, so this has been quite a journey for me. Were you familiar with Welsh history before this? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Don’t forget, the Unruly Figures book is available for presale! My debut book comes out on March 5, but if you preorder now you’ll be able to get it delivered straight to your door that day—and isn’t that the best?

All right, on to the episode!

🎙️ Transcript

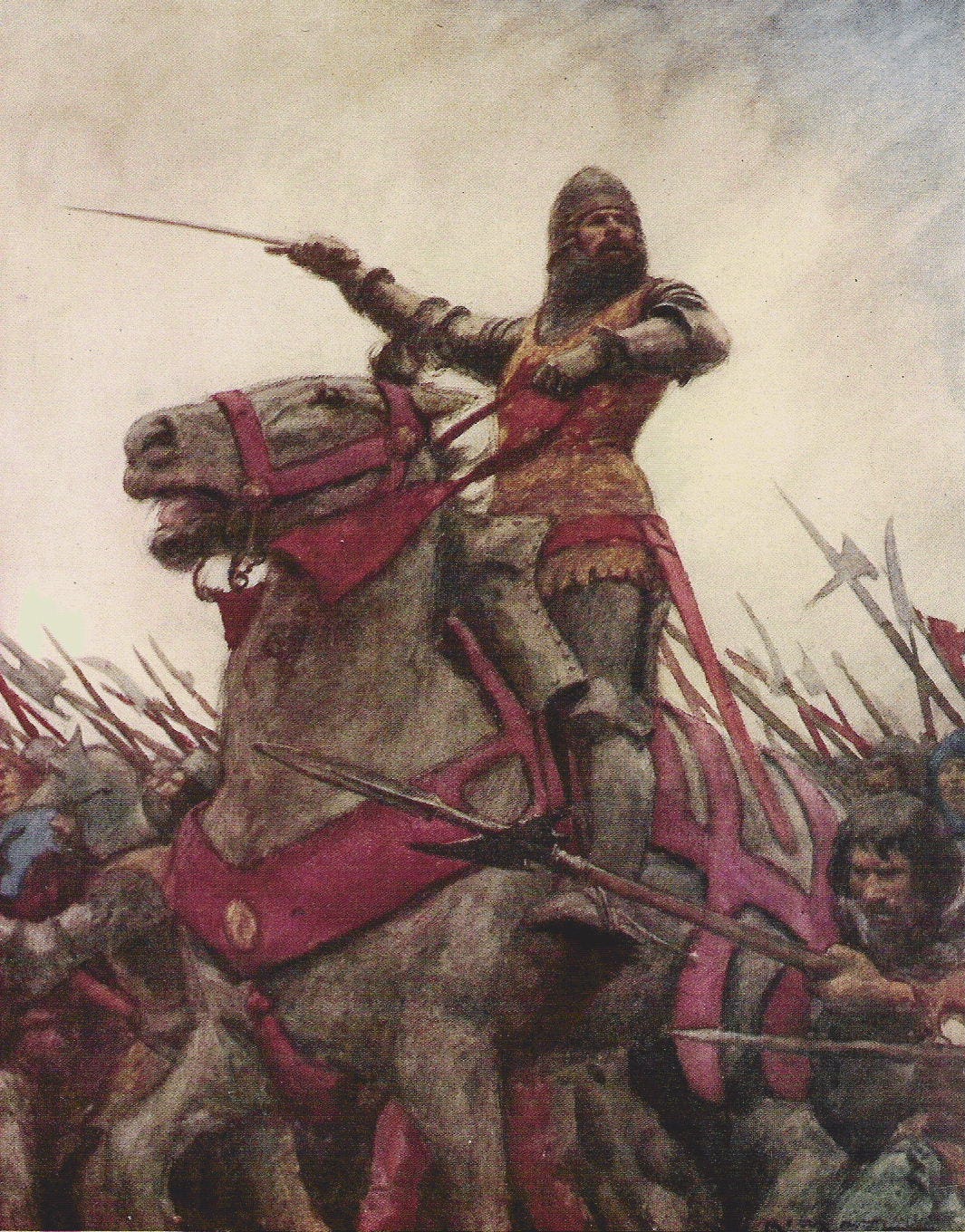

When we think of rebellions against English colonial power, we usually think of the 18th-century American Revolution or the 20th-century Indian Independence Movement. But folks have been rebelling against the English crown much longer than that. As early as the 13th century, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales were fighting against English dominance in the Isles. This is the story of one of those rebellions, led by Owain Glyndŵr, a Welsh prince who might have believed in prophecies of a figure who would free Wales from foreign rule.

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m covering Owain Glyndŵr. He’s a hero to the Welsh people and looms large over Welsh history. Many people compare him to the Scottish Braveheart, but he’s still waiting on his big Hollywood treatment.

But before we jump into Owain Glyndŵr’s life and how he rebelled against the English takeover of Wales, I first have to thank all the paying subscribers on Substack who help me make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! If you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber over on Substack! When you upgrade, you’ll get access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates on the upcoming Unruly Figures book. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

I don’t usually do this, but I think this historical background is going to be unfamiliar to anyone who didn’t grow up in the UK, so before I dive into Owain Glyndŵr’s life, I want to quickly run through some historical highlights leading up to his rebellion. So, as you may know, the Normans were a dominant power from Normandy France who had conquered England in 1066—William the Bastard became William the Conquerer, ruled England and made French the language of the land, et cetera, et cetera. In their invasion, they pushed the then-dominant Anglo-Saxons and the previously-dominant indigenous Celtic Britons west, forcing them to retreat to Wales and northern France, now known as Brittany.

Though the Normans successfully took over the main body of England by the 12th century, they had not effectively invaded and conquered Wales at that time. The conquering of Wales happened much more slowly and gradually, with successive Norman-English rulers slowly pressing further southwest into Wales. It’s worth noting that Wales was not a unified kingdom but more like a few regions who saw themselves as comrades, but not a singular nation-state the way we would think of a nation today.

The Welsh of course fought back, most notably under the rulership of Llywelyn the Great in 1194. His son Dafydd became the first person to hold the title Prince of Wales—up until then the dominant family in Wales had held the title King of Gwynedd.1 The war for English domination of Wales became quite brutal and by 1283 all the men of the house of Gwynedd were dead. Wales as a sovereign nation fell, and the title Prince of Wales was conferred on the young Edward, son of King Edward I of England. Edward was actually born in Wales in 1284, and I covered him a little in my recent bonus episode about royal favorites.

Bonus Episode: What Happens When Royal Favorites Fall Out of Favor

Listen now (13 mins) | Hey y’all, I’m back from my vacation to Morocco and Portugal and back for another bonus episode of the podcast! I will be back with one of our usual episodes next week; thanks again for your patience with the small delay in between episodes. After my Halloween episode on

So, the Welsh were officially a conquered people and region by the end of the 13th century. Unsurprisingly, they were not happy about it. And the fact that they weren’t treated equally under English law made things worse. In a series of successively more restrictive laws, Welshmen saw a lot of their rights stripped away—by 1402 they weren’t allowed to carry arms or wear armor at all, people with castles saw them taken away by the English, they couldn’t hold municipal office, and they had to show up to fight English battles for their English rulers; not turning up when called could invite a treason charge.2 Welsh monasteries and abbeys were, quote, “ransacked” and any documents that confirmed land possession were destroyed so that land could more easily be transferred to English lords.3 Oral tradition has 500 Welsh bards also being, quote, “slaughtered” to erase Welsh history and culture, as well as to prevent discontent from spreading through tales of Welsh heroes.4 It was a pretty bad situation. So this is the world we’re entering into.

Now I have to do my usual warning: We’re talking about the Medieval Era and we don’t know much about Owain Glyndŵr’s young life. Historians are pretty sure he was born between 1354 and 1359 in northeast Wales, near what is now Wrexham—yes the same Wrexham of Ryan Reynolds football investments. Legend has it that his father’s horses stood in blood the night that he was born, and that as a baby his crying could only be comforted by allowing him to touch a weapon.5 This legend about the weapon is also attached to his contemporary Edmund Mortimer, though, so it may just be that the two were conflated for a while and have become confused over time.6

In fact, a ton of prophecy surrounds the story of Owain Glyndŵr, which of course is sometimes hard to separate out from historical fact. On the more basic side is the idea that strange weather and cosmic happenings attended his birth, which increased the swirling rumors of prophecy around him as he grew into adulthood. In his lifetime, people would come to believe that he had the power to control the weather, which is either the source of the strange weather rumors at his birth, or at the very least connected to them. In fact, the mid-14th century was the beginning of a small Ice Age in Europe, so the weather might have been unusually cold.

As for astrological occurrences, comets do pass by Earth with relative frequency—Toutatis usually passes Earth every four years—so it’s possible that one passed by around his birth. People theorize that with cleaner skies and less light pollution in a pre-Industrial world, Medieval people saw more cosmic movement than we can today. Since Halley’s comet passed Earth just before William of Orange’s invasion of England in 10667, the math doesn’t pan out for it to have come by again in time for Glyndŵr’s birth, but who knows what other cosmic occurrences could have happened. An eclipse? A supermoon? Any of these things would have been invested with a lot of meaning in the 14th century.

Perhaps most intriguingly, one of the prophecies often linked to Owain Glyndŵr is the Prophecy of the Six Kings to Follow John. Supposedly told to King Arthur by Merlin, the prophecy foretells of six reigns of English kings, using animals as stand-ins, from, quote, “the Lamb of Winchester to the accursed Mole.”8 The Lamb is, quote, “easily recognizable as Henry III” and the second king-animal, the Dragon, is clearly meant to be Edward I.9 Following the prophecy all the way then, the accursed mole is Henry IV, and it predicts that he will be struck down by a dragon, a wolf, and a lion, who will then split England among themselves while the mole’s, quote, “seed will be completely fatherless in strange lands.”10 Some people suppose that these details were embellished in the early 1400s as part of a political campaign supporting Glyndŵr’s rebellion, but ultimately we’re talking about a Medieval document that started its life as an oral tradition—it has been translated, embellished, and translated again since then, so if it ever was a work of prophecy and not just political propaganda, those details have probably been messed up.

Whether he was foretold or not, Glyndŵr came from royal stock; his father Gruffydd Fychan II was from the Powys family, which had ruled in northern Wales. His mother, Elen ferch Tomas ap Llywelyn, was related to two different Welsh royal houses, Duheubarth and Gwynedd, the family that had long dominated Wales. With all the men of the Gwynedd family wiped out, Welsh people hoping for freedom from England would have naturally looked to someone like Owain Glyndŵr, with his very royal pedigree, as their natural next ruler. There is actually another man from around this time, also named Owain, who folks looked to first—I’m going to cover him in a bonus episode.

But Owain’s life was not really what you’d imagine a young rebel’s life would be like. Maybe people whispered in his ear about what a good ruler of Wales he could make, but it doesn’t seem like he was raised with hopes of overthrowing English rule being installed in him from a young age. His family was powerful, so he probably received a good education and had a comfortable home life, though we don’t know if it was happy or not.

Records of him really begin when Owain’s father died when he was still a young teenager, he was sent to live with the Englishman David Hanmer as his foster son. Hanmer had been raised in Wales and married into Welsh nobility and historians have debated whether Hanmer considered himself English or Welsh. Glyndŵr went on to later marry Hanmer’s daughter, Margaret, which would have required Hanmer’s consent, so people take this as a sign that he identified more with his Welsh surroundings than his English roots.11 But this marriage also occurred before Glyndŵr’s rebellion began so Hanmer might not have really realized that he would be seen as picking sides through it. On top of all this, we don’t know what was going on in the background with Margaret, so I personally find it hard to say that this marriage means Hanmer was betraying his English roots. In any case, he and Margaret eventually had six sons and seven daughters.

It’s worth noting that some people believe that after his father’s death, Glyndŵr was actually sent to live with the third Earl of Arundel, Richard FitzAlan. He was close to the FitzAlan family and they cross paths again several times through this story. Perhaps he lived with the FitzAlans until the third earl died in 1376, then was taken in by David Hanmer. I think this theory only makes sense if Glyndŵr was born in 1359, because he’d be only 16 and would still probably need a foster family in 1376. If he was born earlier, in 1354, then I don’t know how the different foster families make sense. He would have been an adult when the Earl died. So I am not sure how those pieces fit together.

Eventually, historians think around 1380, Glyndŵr was sent to London to study law and then became a legal apprentice, which was a standard 7-year apprenticeship at the time. He was probably in London for the Peasants’ Revolt in June 1381; no telling what he thought of the popular uprising or the brutal repression of it.12 Maybe it served as an inspiration to him. We know that in September 1386 he gave evidence in the Scrope-Grosvenor trial, which was a groundbreaking trial for heraldry. Two different knights had realized that they used the same coat of arms, which makes fighting on a battlefield confusing, and so they turned to the Court of Chivalry to decide who could continue using them. Hundreds of witnesses were called—kind of wish the police would be this thorough with violent assaults today—but again, hundreds of witnesses testified, including now-famous figures like John of Gaunt and Geoffrey Chaucer, and, as I mentioned, Owain Glyndŵr.13

He was only able to testify in this case because, in addition to his law training, Glyndŵr signed up for military work in service of the King of England, Richard II. In 1384, so about halfway through his apprenticeship, Glyndŵr enlisted as part of the retinue of the famous Sir Degory Sais, one of only three Welshmen who had been knighted by the English government at that time. Glyndŵr was stationed at Berwick, on the border with Scotland and England.

I think this fact surprises some people because we tend to think of these sort of home-grown rebels as being against the entire symbol of their oppressors, not specific oppressors themselves. We like to believe that Glyndŵr would have rebelled against any king of England, but that might not be the case. It seems that Glyndŵr was happy to serve Richard II and he would only turn against the English monarchy later in his life. From a 21st-century perspective, we tend to think of Richard II as a bad king, but in 1385 a young Glyndŵr might have seen the young king as someone worth following. But I don’t want to get ahead of myself.

After being stationed at Berwick for several months, Glyndŵr joined King Richard’s campaign north into Scotland in 1385. He was in the troops under the command of John of Gaunt, Richard II’s uncle. This was the campaign where Richard Scrope and Robert Grosvenor realized they carried identical coats of arms. They probably had time to argue because this military campaign has gone down in history as, quote, “a damp squib with no contact being made with the enemy.”14 It sounds like there wasn’t a lot of actual fighting happening, except amongst themselves.

In March 1387, Glyndŵr went out for military service again, this time serving as a squire under the 4th Earl of Arundel, Richard FitzAlan. Instead of north to Scotland, they went southeast to Kent, where they defeated a fleet of Franco-Spanish-Flemish ships at the Battle of Margate—this was part of the much larger Hundred Years’ War. The English forces looted 8,000 large casks of wine from the ships, which was such a huge influx into the normal English wine market that the price of wine dropped throughout all of England for a full year.15 According to historian Adrian R. Bell, the entire city of Flanders called this loss of wine, quote, “the worst disaster to beset that area since the Black Death.”16

Later that year, in December 1387, Glyndŵr served at the Battle of Radcot Bridge. It’s hard to tell whose side he was on at this point—many claim he fought on the side of the defiant Lords Appellant under John of Gaunt’s son, Henry Bolingbroke—later to be crowned Henry IV. If I’m not mistaken, this is the first military action of the Lords Appellant against Richard II. These lords were protesting what they saw as Richard’s tyrannical rule and had tried to have 5 of his favorites banished from court. All though Glyndŵr had supported Richard II up until this point, it’s possible that he had changed his mind and began to see Richard as incompetent. No matter how he arrived and on whose side he fought, we know that Glyndŵr left this battle as enemies with Henry Bolingbroke.

After this battle—which Bolingbroke and the Lords Appellant won—Glyndŵr returned to Wales. His father-in-law, David Hanmer, had passed away during 1387, and Glyndŵr was the executor of his estate, as well as one of the inheritors. What Glyndŵr did once he’d settled the Hanmer estate is a matter of enormous speculation. Some people believe that he chilled in Wales for ten or so years, raising his growing family. Some believe that he returned to London to serve as a squire of the body to Richard II, though others believe he was actually serving Bolingbroke in the same role.17

If he was serving Bolingbroke, that might mean that Glyndŵr was with Bolingbroke when he went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1392 and 1393. It also might imply that when Bolingbroke was briefly banished to France in 1398, Glyndŵr had the choice between going abroad with him or returning home.

Personally, I think he probably stayed home in the 1390s for a few reasons. The first is that upon his return in 1387 or 1388, depending on how long it took him to travel after the Battle of Radcot Bridge, Glyndŵr would have seen the effect of Richard’s tightening noose around Wales. Many historians think he probably hadn’t had many chances to return to Wales between 1380 and 1387, so he might have been shocked by the impact of the new and worsening laws being enacted against the Welsh people. Remember, every year or so, Parliament was coming up with new ways to repress the Welsh in favor of the English. People were losing their homes and jobs, with no recourse for recovery. I just can’t imagine that after seeing all that, he would be eager to serve either Richard II or Henry Bolingbroke.

A second reason would be the known enmity between Bolingbroke and Glyndŵr—the Battle of Radcot Bridge had left Glyndŵr unimpressed with the king’s rebellious cousin. If he left Wales, I doubt it was to serve Bolingbroke.

The third reason I think he stayed home is the records from a poet named Iolo Gogh, who visited Glyndŵr’s castle and seems to have stayed with him for a long time. In his poem “Owain Glyndŵr’s Court,” Iolo portrays his journey as a long-awaited pilgrimage, then describes a beautiful home that’s, quote,

a shelter for poets, a place for everyone,

every day, everyone is allowed there;

fairest timber court, faultless lord,

of the kingdom…18

Meanwhile, things were progressing to a breaking point. In 1397, Richard II executed Glyndŵr’s friend and neighbor the fourth Earl of Arundel; he also executed or exiled a few other members of the Lords Appellant. On July 4, 1399, while Richard was on a military campaign in Ireland, Henry Bolingbroke returned from exile in France with a French army. Despite initially claiming that he had no intention of taking the English crown, he did exactly that on October 13, 1399, becoming Henry IV. Richard II had signed his abdication a couple of weeks earlier and was never seen again.

This was not good for Glyndŵr. The newly crowned Henry IV was not a fan of Glyndŵr, nor of Wales in general. His dislike of the Welsh was so well-known that the region had actually briefly risen up in defense of Richard II that summer, reportedly blocking Bolingbroke’s advances to London.19 This despite how badly Richard II’s rule had treated Wales. Henry IV apparently made things worse by writing decrees forbidding Welshman to wear armor and forbidding Welsh children to be educated; they couldn’t even hold apprenticeships with other Welsh adults. Things were getting worse.

It was also bad for Glyndŵr because Henry IV’s usurpation marked the rise of a wealthy man named Reginald de Grey, who had bought many of the Welsh lands neighboring Glyndŵr’s properties—they had once been owned by the Arundel family and had all been confiscated by the crown when the Earl of Arundel was executed. Grey was a key officiant of Henry IV’s coronation, a former Governor of Ireland, a member of the King’s council, and a peer in Parliament—he held a lot of power, basically, and he used it to start trying to take Glyndŵr’s lands from him.

Around the same time, Henry IV rewarded Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy, Earl of Northumberland, for his loyalty by making him the Lord High Constable; he also granted Hotspur the Justiciaryship of North Wales, a very powerful position. If Hotspur sounds familiar, it might be because he’s one of Shakespeare’s most famous characters ever. He also lends his nickname to the modern football team, the Tottenham Hotspurs. I bring him up now only so we don’t have to backtrack when he becomes important to the story, so just keep Hotspur in mind.

Several times in 1399, Glyndŵr formally protested against Lord Reginald de Grey’s attempts to take his land. Parliamentary records specifically name a town or property called Croesau, which is close to the north coast of Wales and the Welsh/English border. Before Richard II was captured, he’d ruled in Glyndŵr’s favor, but once Henry IV took over, Lord Grey reclaimed the land and further requests for Parliamentary rulings were ignored. Instead of hearing his case in the Spring of 1400, they said, quote, “What care we for barefoot Welsh curs?” and told Glyndŵr to grant Lord Grey further concessions.20 Glyndŵr left London fuming.

A few months later, Henry IV issued a muster for forces to fight for England in Scotland. All the barons, who had been required to pledge loyalty to Henry IV, were required to show up with a certain number of men. Somehow, Lord Grey intercepted Glyndŵr’s muster letter and didn’t pass on the orders until it was too late for Glyndŵr to respond in time—too late to even send a letter explaining his absence. Ignoring an order of the King was considered treasonous, and the result would have been the seizure of Glyndŵr’s estates—a result Lord Grey obviously wanted.

It seems, however, that that didn’t work quickly enough for Lord Grey, because in early September 1400, he invited Glyndŵr to a reconciliation meeting with a letter carried by friars of a local monastery.21 This would have made his request for reconciliation seem more genuine; it’s a big deal to lie to men of the Church, after all. They set up a meeting at Glyndŵr’s court on the condition that Grey arrived with only 30 armed followers; he lied, of course, and brought a much larger and heavily armed party.

The poet I mentioned earlier, Iolo Goch, is apparently the man who noticed the extra soldiers hidden in the darkness outside Glyndŵr’s home. In a story that sounds like it was written for a movie, Goch delivered a warning to Glyndŵr by reciting a poem that somehow hinted at the secret attack and Glyndŵr got away.22 However, since Goch and Glyndŵr both spoke Welsh and Lord Grey didn’t, I doubt he needed to go through the whole operatic nonsense of publicly reciting a poem when he could have just like…whispered in his ear or something. Obviously, the poetic version is more, well, poetic, and if Glyndŵr does get a movie treatment, this performance will probably be in it, but we should all know it probably didn’t happen that way.

Either way, Glyndŵr escaped just before Lord Grey’s men attacked. He went into hiding in the mountains of Wales with a very small force of men. It’s frequently said that this is the moment that Glyndŵr realized he would never be able to get justice through legitimate means. His legal options exhausted, Glyndŵr began his war on September 16, 1400. He was proclaimed Prince of Wales at his court at Carrog and raised his royal family’s flag as part of the fight; some call this “the standard of national revolt,” though I’m not totally clear on whether that is a result of Glyndŵr’s fight or if that was already a known association.23 Bards quickly spread the news, and 250 men volunteered to join his battle.

Glyndŵr’s lands were soon confiscated, and he began a guerilla campaign to drive the English out of Wales. Considering the discriminatory policies that the Welsh had been dealing with for years, it wasn’t hard for him to find broad support. He began with burning Lord Grey’s lands both as retaliation for everything Lord Grey had done up to then, but also to economically hinder him—Grey needed the rents and income from those lands to fund his fight against Glyndŵr. They began burning a few other towns as well, and some towns were burned so frequently throughout this rebellion that they became known as “Burnttowns,” all one word.24

In June 1401, Hotspur was sent to crush Glyndŵr’s rebellion. They met at Dolgellau in northwest Wales, the heart of Glyndŵr’s supporters. He sent back a message to Henry IV boasting of his success at destroying the men, but it was a lie. The battle was a draw.

Hotspur engaged Glyndŵr’s forces several more times. I’m not going to get into every battle, but suffice it to say that it was not going well for Hotspur’s forces because they just didn’t know the land as well. Glyndŵr’s men could attack and melt away into the hills because they just knew Wales better. Meanwhile, word of his rebellion was spreading, and educated Welsh men from the University of Oxford began traveling back to Wales to support the rebellion. Hotspur changed tactics eventually and instead of bragging and boasting, he began writing urgently to Henry IV, encouraging him to issue a general pardon for North Wales if the men there would put down their weapons. It seems that, when Parliament gathered that fall, they briefly considered settling the Welsh question with a treaty for peace, but nothing came of it, probably due to the influence of Lord Grey.25

That fall, Glyndŵr traveled to Caernarfon Castle in Gwynedd (northwest Wales). There, he raised the famous and extremely symbolic flag of Uther Pendragon—a golden dragon on a white shield. It symbolized that Owain Glyndŵr was now the Prince of Wales and King of the Britons, a reclamation of independence that hadn’t been possible since Llewelyn the Great. It also invoked the ancient Britonnic stories of King Arthur, who is not as popular in Welsh lore, but known and it linked Glyndŵr with the legends of great saviors and redeemers who freed oppressed peoples. This is a symbolic and important power move that Glyndŵr is making, and it brought out more supporters who had been hesitant before.

In fact, Glyndŵr kept succeeding militarily against all odds. Since Welsh men had been banned from wearing armor or owning weapons, at first there weren’t a lot of men who could fight in this rebellion, and people were understandably nervous during the early stages. But the more Glyndŵr succeeded against the larger and stronger English army, the more volunteers showed up to fight for Welsh freedom. And legends began to grow about how Glyndŵr was so successful—rumors began to spread that he could control the weather because the English army was repeatedly stopped from attacking by torrential rains, flooded rivers, heavy fogs, and more. His contemporaries thought he was a witch of some sort, or aided by witches.

Glyndŵr leaned into this aura of magic and mystery. In addition to probably spreading the prophetic legends of his own birth, he famously consulted a master of prophecy whose name I’m going to absolutely slaughter, and for that I’m sorry. The man was Hopcyn ap Tomas ab Einion of Ynys Forgan—he was a, quote, “renowned bibliophile, recognized for his knowledge of Welsh lore.”26 While he may have made predictions of his own about Glyndŵr, he was probably equally useful for learning about other prophetic possibilities. Hopcyn may have described many different prophecies to Glyndŵr; we know Hopcyn was lamenting the loss of Welsh culture through English domination and was busy documenting Welsh oral stories and traditions when Glyndŵr called on him.27 Glyndŵr also employed a prophet full time, a man named Crach y Ffinnant, but apparently wanted a second opinion to find out what might happen to him—was he the deliverer that old Welsh lore promised?28 I think to modern ears this interest in prophecy can seem strange strange, but Medieval prophecies often had their roots in Biblical lore and were used for political currency.29 Unfortunatley, exactly what Hopcyn told him and whether Glyndŵr believed it beyond what it could mean for his political legitimacy is more or less unknown.

Glyndŵr’s enemies grew frustrated as the battles in Wales dragged on. Hotspur and the rest of the Percy family were increasingly split between their military obligations in Wales and their military obligations in Northumberland, a region on the border between Scotland and England. They were basically tasked with maintaining England’s two land borders, and both were experiencing rebellions and uprisings. Worse, they were doing this alone. Henry IV stopped paying wages to the soldiers at some point, and the Percy family was funding all of this fighting from their own pockets, which were quickly turning up empty.

There’s some historical debate about when the Percy family turned their backs on Henry IV. Both Henry ‘Hotspur’ Percy and his father, also named Henry Percy—truly, too many Henrys in this story—had both fought for Henry Bolingbroke when he usurped the throne from Richard II in 1399, but in 1403 they were openly rebelling against the new king. Some historians claim that Hotspur was against Henry the whole time, colluding with Owain Glyndŵr and the Welsh as early as Glyndŵr’s declaration in September 1400. The proof may be in the lies he told Henry IV about how his battles against Glyndŵr were going. But others claim that his change of heart came later, only once he started fighting against Glyndŵr in Wales.

What we do know is that Hotspur and Glyndŵr were related through marriages to the Mortimer family. Hotspur was married to the third Earl of March Edmund Mortimer’s eldest daughter Elizabeth, while Glyndŵr’s daughter Catrin married Edmund Mortimer’s son, also named Edmund, the fourth Earl of March, in 1402. Hotspur and Glyndŵr probably crossed paths at various battles for Richard II, but a lot of people point to this familial connection as the beginning of the joint Glyndŵr-Percy rebellion.

Unfortunately, Hotspur was killed early in the rebellion. He died at the Battle of Shrewsbury just months after they openly declared against the king. But his father remained in the fight—in February 1405 Henry Percy senior, Owain Glyndŵr, and Edmund Mortimer junior came to an infamous agreement: The Tripartite Indenture. The document—contemporary summaries of which survive to today30—laid out how the three would lead the rebellion against Henry IV, and then how they would govern England and Wales once he was overthrown. It was pretty straightforward: Glyndŵr would take Wales and some of west England, the Percies would have northern England, and the Mortimers would have southern England. Importantly, it doesn’t divide the land into separate kingdoms but the three families would rule over the country as a kind of council together.31

Around the same time that Glyndŵr was negotiating this Tripartite Indenture, he was also contacting the French king Charles VI for military support. On January 12 1405, Glyndŵr signed the aptly titled Confederation Between Wales and France which promised French aid against Henry IV. That Glyndŵr was sending ambassadors abroad—who were taken seriously—speaks to how strong his rebellion was. In fact, by 1404, he had more or less control over Wales. He established a separate Parliament, which met and issued laws, and ecclesiastical control in the region. His army swelled and he was recognized as the Prince of Wales, an independent principality once again, even if that wasn’t a signed treaty yet. Really the only thing dragging the rebellion on was Henry IV’s refusal to believe it was over. He just kept sending men to die in Wales.

Unfortunately… that plan of Henry IV’s worked. Without getting into all of the battles—because the documentation is confusing, so there’s a lot of question marks next to dates—Glyndŵr’s grip on Wales started to slip in 1405. Henry IV was a surprisingly bad military commander (that had actually been one of the many issues Hotspur had taken with him) and the king was convinced to turn over military control to his son and heir, who Shakespeare immortalized as Prince Hal. The prince turned out to be a much better commander than his father, and Glyndŵr’s forces suffered major losses as the battle season got underway in 1405. French reinforcements, though promised, arrived too late. The Percies and Mortimers in England were crushed as well, and the tide of battle turned against the rebellion. Prince Hal slowly but surely marched further into Wales, recapturing Glyndŵr’s strongholds and crushing resistance.

A lot of people put the ending date of the rebellion at 1408 or 1409. That’s sort of when we see the last major battles and when Prince Hal’s grip on Wales became complete. There were some final gasps of rebellion—some ongoing guerilla tactics into at least 1412, maybe as late as 1416. But it was pretty much over years before that.

The interesting part of this is that we don’t know what became of Owain Glyndŵr. Normally when rebellions are put down, especially in the Medieval Era, we see the leader’s dead body put on display to prove that the rebellion’s main cause was over. But that didn’t happen with Glyndŵr. If he was caught, those documents don’t exist, and no one records him being executed and his body displayed. We know that in 1415, Prince Hal—by then King Henry V—offered Glyndŵr a pardon, but that he didn’t take it.32 That indicates that he survived at least until 1415 and people knew where to reach him. We know that he spent his final years on the run; his family had been arrested and was held more or less hostage by the English royal family, and rather than be executed most people believe Glyndŵr hid in caves and with sympathetic friends for the rest of his life.

Most historians place Glyndŵr’s death in 1416, and legend has it that he’s buried at Monington Court, the home of his son-in-law John Scudamore.33 But a better legend has it that, like King Arthur, Owain Glyndŵr is somewhere waiting for his chance to return to Wales and free his homeland.

That is the story of Owain Glyndŵr! If you want to learn more about Owain Glyndŵr, I really recommend the book Owain Glyndŵr: A Casebook, which contains a unique collection of original documents related to Glyndŵr, as well as essays by scholars interpreting them. If you liked this story, you are going to love my book, Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of. It’s out March 5, 2024, but you can preorder it now. You can let me know your thoughts about this or any other episode on Substack, Twitter, and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it does help other folks discover the show.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Castellanos Clark. My research assistant is Niko Angell-Gargiulo. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email at hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com If you’d like to send us something, you can send it to P.O. Box 27162 Los Angeles CA 90027.

Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

“ASTEROID’S FLY-BY SENDS ‘HEADS-UP’ TO EARTH - The Washington Post.” Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1996/11/28/asteroids-fly-by-sends-heads-up-to-earth/73e961e1-bd94-4e8d-bde4-a1907ace286a/.

Breverton, Terry. Owain Glyndŵr: The Story of the Last Prince of Wales. Amberley Publishing, 2012.

Cartwright, Mark. “Peasants’ Revolt.” In World History Encyclopedia. World History Publishing, January 23, 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/Peasants'_Revolt/.

———. “Richard II of England.” In World History Encyclopedia. World History Publishing, January 22, 2020. https://www.worldhistory.org/Richard_II_of_England/.

Dean, John Candee. “The Astronomy of Shakespeare.” The Scientific Monthly 19, no. 4 (1924): 400–406.

Dodd, Arthur Herbert. “HANMER Family of Hanmer, Bettisfield, Fens and Halton, Flintshire, and Pentre-Pant, Salop.” In Dictionary of Welsh Biography. The National Library of Wales and the University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies, 1959. https://biography.wales/article/s-HANM-HAN-1388.

Doig, James A. “The Prophecy of the ‘Six Kings to Follow John’ and Owain Glyndwr.” Studia Celtica XXIX (1995): 257–67.

Fulton, Helen. “Owain Glyndwr and the Prophetic Tradition (Book Chapter).” In Owain Glyndwr: A Casebook. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013. https://www.academia.edu/23672089/Owain_Glyndwr_and_the_Prophetic_Tradition_book_chapter_.

Goch, Iolo. Owain Glyndŵr’s Court. 1390s. Poetry. https://www.owain-glyndwr.wales/pdf_files/IoloGochPoemSycharth.pdf.

Harvard University. “The Scrope-Grosvenor Trial (1385-1390).” Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://chaucer.fas.harvard.edu/pages/scrope-grosvenor-trial-1385-1390.

Henken, Elissa R. “Three Forms of a Hero: Arthur, Owain Lawgoch, and Owain Glyndŵr.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 15 (1995): 22–31.

Historic UK. “Owen Glendower (Owain Glyndwr), Last Welsh Prince of Wales.” Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/Owen-Glendower-Owain-Glyndwr/.

Howell, Elizabeth. “Halley’s Comet: Facts About the Most Famous Comet.” Space.Com, January 13, 2022. https://www.space.com/19878-halleys-comet.html.

Johnson, Ben. “Kings and Princes of Wales.” Historic UK. Accessed November 18, 2023. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/Kings-Princes-of-Wales/.

———. “The English Invasion of Wales.” Historic UK. Accessed November 18, 2023. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/The-English-conquest-of-Wales/.

Kay, Morgan. “Prophecy in Welsh Manuscripts.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 26/27 (2006): 73–108.

“Kings and Queens from 1066.” Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.royal.uk/kings-and-queens-1066.

Livingston, Michael. “Owain Glyndŵr’s Grand Design: ‘The Tripartite Indenture’ and the Vision of a New Wales.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 33 (2013): 145–68.

Livingston, Michael, and John K. Bollard, eds. Owain Glyndwr: A Casebook. 1st edition. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013.

“Medieval Soldier - David-Le-Hope-and-Sir-Gregory-Sais.” Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.medievalsoldier.org/about/soldier-profiles/david-le-hope-and-sir-gregory-sais/.

Medievalists.net. “How Accurate Were Medieval Chroniclers in Describing Warfare?” Medievalists.Net (blog), March 22, 2011. https://www.medievalists.net/2011/03/how-accurate-were-medieval-chroniclers-in-describing-battle/.

“Owain Glyn Dŵr | Welsh Prince, Rebellion Leader | Britannica.” In Encyclopædia Britannica, September 25, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Owain-Glyn-Dwr.

“Owain Glyndŵr.” You’re Dead to Me. BBC Sounds. Accessed November 18, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p09zf4r9.

“Owain Glyndŵr.” In Oxford Reference. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095856671.

Pierce, Thomas Jones. “OWAIN GLYNDWR (c. 1354 - 1416), ‘Prince of Wales’ | Dictionary of Welsh Biography.” In Dictionary of Welsh Biography. The National Library of Wales and the University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies, 1959. https://biography.wales/article/s-OWAI-GLY-1354#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&manifest=https%3A%2F%2Fdamsssl.llgc.org.uk%2Fiiif%2F2.0%2F4672503%2Fmanifest.json&xywh=879%2C949%2C569%2C459.

Sky HISTORY TV channel. “Owain Glyndŵr: The Last Welsh Prince of Wales.” Accessed November 18, 2023. https://www.history.co.uk/shows/al-murray-why-does-everyone-hate-the-english/articles/owain-glyndwr-the-last-welsh-prince-of-wales.

Smallwood, T. M. “The Prophecy of the Six Kings.” Speculum 60, no. 3 (1985): 571–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/2848176.

The History Press. “The History Press | Three Things You Might Not Know about Owain Glyndŵr.” Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/three-things-you-might-not-know-about-owain-glyndŵr/.

Turner, Robin. “Prince George Related to Llywelyn the Great, Claims Genealogist.” Wales Online, July 31, 2013, sec. Latest Wales News. http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/prince-george-related-llywelyn-great-5385491.

Williams, Professor Gruffydd Aled. “The Medieval Welsh Poetry Associated with Owain Glyndŵr” The British Academy, 2010. https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/778/BAR17-08-Williams.pdf.

Ben Johnson, “Kings and Princes of Wales,” Historic UK, accessed November 18, 2023, https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/Kings-Princes-of-Wales/.

Terry Breverton, Owain Glyndŵr: The Story of the Last Prince of Wales (Amberley Publishing, 2012).

Breverton, “Introduction”

Breverton, “Introduction”

Breverton, “Glyndŵr’s Early Life & Family”

Breverton, Glyndŵr’s Early Life & Family”

Elizabeth Howell. “Halley’s Comet: Facts About the Most Famous Comet.” Space.Com, January 13, 2022. https://www.space.com/19878-halleys-comet.html.

James A. Doig, “The Prophecy of the ‘Six Kings to Follow John’ and Owain Glyndwr,” Studia Celtica XXIX (1995): 257–67.

T. M. Smallwood, “The Prophecy of the Six Kings,” Speculum 60, no. 3 (1985): 571–92, https://doi.org/10.2307/2848176.

Michael Livingston and John K. Bollard, eds., Owain Glyndwr: A Casebook, 1st edition (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013).

Arthur Herbert Dodd, “HANMER Family of Hanmer, Bettisfield, Fens and Halton, Flintshire, and Pentre-Pant, Salop,” in Dictionary of Welsh Biography (The National Library of Wales and the University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies, 1959), https://biography.wales/article/s-HANM-HAN-1388.

Mark Cartwright, “Peasants’ Revolt,” in World History Encyclopedia (World History Publishing, January 23, 2020), https://www.worldhistory.org/Peasants'_Revolt/.

Harvard University, “The Scrope-Grosvenor Trial (1385-1390),” Harvard’s Geoffrey Chaucer Website, accessed January 11, 2024, https://chaucer.fas.harvard.edu/pages/scrope-grosvenor-trial-1385-1390.

Mark Cartwright, “Richard II of England,” in World History Encyclopedia (World History Publishing, January 22, 2020), https://www.worldhistory.org/Richard_II_of_England/.

Medievalists.net, “How Accurate Were Medieval Chroniclers in Describing Warfare?,” Medievalists.Net (blog), March 22, 2011, https://www.medievalists.net/2011/03/how-accurate-were-medieval-chroniclers-in-describing-battle/.

Medievalists.net

Breverton, “Glyndŵr’s Early Life and Family”

Iolo Goch, Owain Glyndŵr’s Court, 1390s, Poetry, 1390s, https://www.owain-glyndwr.wales/pdf_files/IoloGochPoemSycharth.pdf.

Breverton, “Glyndŵr’s Early Life and Family”

Breverton, “Glyndŵr’s Dispute with Lord Grey”

Breverton, “Glyndŵr’s Dispute with Lord Grey”

Breverton, “Glyndŵr’s Dispute with Lord Grey”

Breverton, “Rebellion of Glyndŵr, the War Begins 1400”

Breverton, “Rebellion of Glyndŵr, the War Begins 1400”

Breverton, “War Across Wales 1401”

Morgan Kay, “Prophecy in Welsh Manuscripts,” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 26/27 (2006): 73–108.

Kay, 98

Kay, 73 and 98

Kay, 73

It’s worth noting that the authenticity of the surviving copies of the Indenture have been debated for some time. However, I think Michael Livingston makes a great case for the known copies at the British Library to be authentic and at least copied from the original, if not actually original copies themselves.

Michael Livingston, “Owain Glyndŵr’s Grand Design: ‘The Tripartite Indenture’ and the Vision of a New Wales,” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 33 (2013): 145–68.

“Owain Glyndŵr,” in Oxford Reference, accessed November 19, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095856671.

“Owain Glyndŵr” in Oxford Reference

Share this post