Hey everyone,

I am so excited to bring you this week’s episode on Hatshepsut, an incredibly audacious, ambitious, and ultimately talented woman from Ancient Egypt. She stepped into the role of king, despite the fact that it broke every rule of royal womanhood, and created such a successful reign that it became a threat to her successors.

Unruly Figures is dedicated to making complicated history more accessible and interesting for non-historians. If you love this mission, please support this project—your pledge will help me access paywalled archives and ensure that I can keep doing this in-depth research and creating these episodes.

🎙️ Transcript

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m covering Hatshepsut, a woman who used her deep theological knowledge of ancient Egypt to rise to its most powerful position: King.

But before we jump into Hatshepsut’s life and how she became one of the greatest kings of Egypt, I want to thank all the paying subscribers on Substack who help make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! Each of these episodes takes me nearly 30 hours of work, which means they’ve become a full-time job. So if you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber for just $6/month or $60/year! Contributions help ensure that I will be able to continue doing this work. Becoming a paying subscriber will also give you access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates on the upcoming Unruly Figures book. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

Also a small trigger warning right up front. We’re talking about Egyptian royalty here, so we’re also going to talk a little about incest. The two just go hand-in-hand, sorry. I’ll try to warn you when that topic comes up, but if I forget, I apologize!

Okay, let’s hop in.

For this episode, I’m relying a lot on Kara Cooney’s excellent and recent biography of Hatshepsut, The Woman Who Would Be King. There’s a lot of information out there about this female ruler, but a lot of it is conjecture and I think Cooney does a good job of being really clear about what is fact and what is conjecture or guesses.

And for good reason! The difficult part of creating a story for any Egyptian pharaoh is that their personal histories are often left untold. Biographer Kara Cooney writes that the king was quote, “meant to bea living god on earth, [so] naturally he had to be shrouded in ideology dn not defined by his personality, schemes, plans, and ambitions.”1 The rulers of Egypt were meant to be vessels of their gods, and as such couldn’t be publicly depicted having human fallibilities like ambition, doubt, fear, greed, excitement, joy—it’s very austere. Quote, “The system of diving kingship and cosmic order mattered most to [the ancient Egyptians], not the individual person who was king at a particular time. The institution of kingship was unassailable.”2 The ancient Egyptians quote, “never underestimated the power of the written word; anything that smacked of personal politics or individual opinion was excluded from the formal record… [they] preserve the ‘what’ of their history in copious texts and monuments for posterity; the ‘how’ and the ‘why,’ the messy details of it all, are much harder to get it.”3

Fittingly, we only understand Hatshepsut through the things she built—and how they were destroyed.

Hatshepsut was born around 1500 BCE, during the Eighteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom, though she wouldn’t have used any of those terms to describe it. This was a moment of prosperity and dominance for Egypt—they had recently subjugated Nubia, their neighbor to the south, which was rich in natural resources like gold. And if you’re interested in hearing more about Nubia, get on the list to pre-order my book, I talk about one of Nubia’s fiercest rulers in it.

Obligatory self-promotion aside, Hatshepsut was part of the Thutmoside dynasty; Thutmose I was her father. He had been chosen to reign after Amenhotep I had no surviving family except his mother, who had been his regent. It’s unclear how Thutmose was chosen; Cooney guesses he had some sort of familial connection Amenhotep, but he definitely wasn’t one of the previous ruler’s sons. Whatever his previous life, it would have all gone away when he took on this mantle—he would have known that, quote, “kingship was essential to the survival of Egypt and the Egyptian people. Politics and religion went hand in hand in Egypt: if there was no king, there was only cosmic chaos.”4

It’s unclear if he was married or had children before this, but I sort of hope he wasn’t because this would have been a difficult transition for them. For Thutmose, monogamy also went out the window by necessity. Pharaohs had a King’s Great Wife, whom they hoped to have a son with to continue the line. But by the eighteenth dynasty, the reality of the difficulty in bearing a son who survived to adulthood had been thoroughly realized. Again, we’re talking about 1500 BCE, medicine just wasn’t the same as it would be even in 1500 CE. Henry VIII had better chances of keeping his children alive, and we saw how that turned out. So pharaohs were basically required to have multiple sexual partners, who were all called King’s Wives, because they needed to have as many children as possible just to hope that one boy would survive! Cooney characterizes it as, quote, “he was considered the bull of Egypt: royal sex was linked to the ongoing creation of the cosmos itself.”5 He was probably expected to have sex with his new Great Wife Ahmes or one of the other “lesser” Kings Wives every night that he was in the royal residence. If he was married before this moment, Ahmes superseded his first wife and it’s unclear if that hypothetical first wife would have been allowed to stick around.

And if he had children from before he ascended the throne, they could not inherit the throne because they would have been born from a non-royal, non-religious union. He would have gone through a ritualistic process that would have enabled him to become a vessel of Horus so he could rule; only children born to him after that could have inherited.

So Hatshepsut was born to Thutmose I and his Great Wife Ahmes. And this is the part where incest comes up. Traditionally, pharaohs married their sisters. For ancient Egyptians, incest was pretty much only practiced among royalty, that we know of, and it was very much related to the fact that the pharaoh was also meant to be a divine figure, a vessel of Amen-Re. The mythology of the Egyptian pantheon included a lot of incest—Atum, the first god, had to have sex with himself to be born, quote, “magically producing his own birth and subsequently the first generation of male and female gods. The brother-sister pair, Shu and Tefnut, copulated with each other and produced the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut.”6 And so on and so forth. Through this lineage, Horus, king on earth and the god that pharaohs embodied was the son of another of those brother-sister pairings. So incest was seen as holy for Egyptian royalty, and royal daughters would have only had the option to marry a future pharaoh, who would also be at least their half-brother—it was him or celibacy for life. There were literally no other options, and we see very few marriages between royal daughters and quote-unquote “commoners” during this period of Egyptian history. Of course, if you study ancient Egyptian history, this practice also probably contributed to a lot of succession crises because after a couple of generations, sibling couples either can’t produce offspring or their offspring is severely ill as a result.

To make this practice more comfortable, male and female siblings were raised separately. They wouldn’t have had a typical sibling relationship as we think of siblings today who are raised in the same household. And, spoiler, Hatshepsut will also marry a brother who she barely knew before they were married.

But, there’s reason to believe that Thutmose did not marry his sister. If he did, it would have been difficult since they would have been raised in a non-royal household where they would have established a sibling relationship. Most Egyptologists guess that Ahmes was related to someone in the previous ruling family, possibly Amenhotep I’s sister. It would have given Thutmose more legitimacy to be married to someone from that family.

All that to say—Hatshepsut was born to Thutmose and his Great Wife, Ahmes. But we think that she was their only child. Interestingly, this lack of a boy child would not have been blamed on Ahmes, which I feel like is the European tradition. Instead, in ancient Egypt, quote, “the responsibility for infertility was laid at the feet of the man…a human man—or a king—was believed to contain the spark of creation.”7 The woman was not the creator of a new life, she was just the vessel for it.

That said, there is an idea that Hatshepsut had two highly placed brothers named Wadjmose and Amenmose. They may have been full brothers, born to Ahmes after Hatshepsut, but historians are not sure. They were, at some point, destined to become the next king of Egypt, but then something went wrong; both boys died, but sources are silent on how or when.

She probably was not raised by Ahmes, who would have had duties to attend to, as well as needed to get ready to have her next child. Cooney also points out that so few infants survived infancy that royal mothers may have just, quote, “refused to acknowledge the existence of her infant child because it might not live out the year [and] such losses were too painful to take over and over again.”8 Instead, Hatshepsut was mostly raised by a noblewoman named Satre, who started as her wet nurse but grew to be a beloved figure in the young princess’s life. Nursing a king’s child was considered a great honor, and they often nursed until they were at least three years old. Satre would have also mothered her in other ways—she would have changed her diaper and held her through fevers, giving her things to chew on when teething and taking away things she tried to eat that would have killed her.

It was another King’s Wife, who also bore the title King’s Sister, who gave birth to a son first. Her name was Mutnofret, and she named her son Thutmose. She also later had a daughter named Neferubity, who Hatshepsut became very close to. Why Mutnofret wasn’t the King’s Great Wife is debated by Egyptologists—perhaps she was just too young to get married when Thutmose came to the throne.

Cooney supposes that Hatshepsut grew up knowing she was special. She was the eldest daughter and only child of the king’s highest-ranking wife. People would have deferred to her since she was a young child, and she would have spent a lot of time in the temples, talking with the god Amen or the goddess Mut. She also would have received the best education in the land. It’s around this time that one of the most important players in Hatshepsut’s life enters the picture: Senimen. He was one of her tutors, and he left dozens of statues and records testifying to their close relationship. He became like a father to her, as well as an ally and adviser.

When she was still quite young, maybe four or five, she began training for the most powerful position a woman could hold in ancient Egypt: God’s Wife of Amen. With that came a great amount of education, and she would have started working with tutors at a very early age in order to memorize the dozens if not hundreds of incantations and movements that would be her responsibility someday. She probably shadowed Ahmes-Nefertari, mother of Amenhotep I, and/or Merytamen, wife of Amenhotep I. They both acted as God’s Wives in addition to their roles as pharaoh’s wives.

The job as God’s Wife was intense. In addition to secret rituals and long incantations, the wife had to wake the god’s statue up every morning, helping him be reborn through a masturbatory ritual on his erect statue as well as guiding him through his first meal each day with incantations. According to Cooney, the ceremony might have felt, quote, “psychedelic” with lots of incense, chanting, swaying, drumming, and dancing.9

It was, however, a very private ceremony, witnessed only by the highest priests of the temple, if even them, because it required the God’s Wife to remove all her clothing during it. It’s unclear when Hatshepsut took on the mantle, but she may have been “very young" because Thutmose would have wanted the influential position held by a member of his own family.10 There’s also little evidence that the ancient Egyptians at all, quote, “shielded children from human sexuality…If Hatshepsut’s destiny was to become the God’s Wife of Amen herself, to connect the god’s rebirth to her father’s kingship, then she had to begin her training early, including knowledge of the more sexual aspects of the job."11

These women from the Ahmoside family would have modeled female authority to Hatshepsut. The office of God’s Wife was second in religious authority only to the High Priest of Amen, and it came with estates and palaces that they owned outright, as well as staff to help manage her affairs. It’s worth noting that this religious order was analogous to the Vatican in some ways, quote, “a force to be reckoned with, both economically and politically, and even the king needed to tread lightly.”12

Once Hatshepsut formally became God’s Wife, she also would have moved out of the nursery into her own rooms in the palace. With no concept of adolescence or teenagers, she would have been considered an adult no matter how old she really was, though I think we can guess that she would have still been a child to modern eyes. As a highborn lady in Egypt, she would have usually worn a, quote,

“long, narrow, linen shift of the finest, most gossamer, royal fabric, enhanced with sharply pleated linen robes of diaphanous thinness…Her sandals were made from the softest leather… She wore kohl around her eyes which not only protected her from the glares of the harsh sun but also kept away some of the more violent eye diseases. She was now expected to wear a wig over her own hair...a full, structured hairpiece made of human plaits and braids cut from the heads of many peasant women who may or may not have been happy to give their locks to serve the God’s Wife. A diadem of delicate filigreed stars likely adored her wig. On her wrists and upper arms she wore solid gold bands, and her fingers bore elaborate rings, some of the golden scarabs…”13

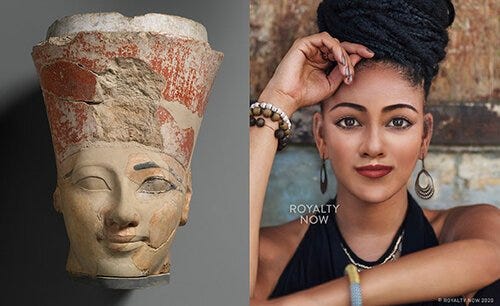

We really have no idea what she looked like though. Portraits of her were commissioned by her, and so were naturally flattering. They definitely wouldn’t have revealed the reality of life at this time, where people were often sick with long-term illnesses like tapeworms or other infestations that could alter how they looked. If she had, say, lost an eye to infection during childhood, or had acne scarring, or anything else, we’d never know. There are rumors that in her later years, she was obese, bald, and had bad teeth—some of this may just be part of squashing her legacy, and we’ll come back to that.

Her role as God’s Wife meant that Hatshepsut had roles politically. She would have been in the throne room alongside her father, proof of the family’s power. She would have brought messages from her father to the god Amen and back. So she would have witnessed how he enriched Egypt during this time, bringing back a lot of gold from his conquest of Nubia and other military campaigning. He built many temples, and in fact was one of the first rulers to quarry stone to do so, rather than building out of mudbricks that were so easily destroyed. She would have understood how building projects provided jobs for Egyptians, worship for the gods, and propaganda for the royal family.

There’s a common misconception about these building projects—Ancient Egypt has often been seen as a land of intense slave trade and abuse, with thousands of slaves dying in heartless building projects for narcissistic pharaohs. While it’s hard to generalize across three centuries of an empire, it is worth noting that that’s not quite reality—importantly, large-scale building projects were given to paid Ancient Egyptian locals because they would have cared more about the project than enslaved people who didn’t fully understand what they were building.14 They weren’t often built by enslaved people. Slavery also wasn’t the brutal picture of chattel slavery we hold today—enslaved people occupied a more liminal space, and sometimes held property or earned money, much like I talked about in the Yasuke episode. That doesn’t make it okay, obviously, but it was a very different system than the popular understanding.

It was at some point during this adolescence that Hatshepsut’s brothers died. Cooney guesses she was about 12. Her next oldest brother, Thutmose, would have been significantly younger, and no matter when he came to the throne, he would have been less educated and less experienced than her. As the dynastic inheritance was negotiated and figured out after the deaths of both Wadjmose and Amenmose, Hatshepsut might have realized that, quote, “if she were to marry one of her younger brothers, she would serve as his guide, as a decision maker, perhaps even as the power behind the throne.”15 Thutmose I would have been about 50 years old by this point, and probably aware that—even though he was relatively healthy—he could go at any point simply because of the vagaries of illness in 1500 BCE.

The next prince they picked was the young Thutmose, a boy who was probably never very healthy. If his mummy has been identified correctly, then, quote, “his skin was covered with lesions and raised pustules. He had an enlarged heart, which meant he probably suffered from arrhythmias and shortness of breath.”16 He was probably, at most, nine or ten years old at the time.

And before they could even really begin training him for the throne, Thutmose I passed away. At just nine years old, Thutmose II was far too young to fully take the throne, so he needed a regent. And somehow, Hatshepsut’s mother stepped in as regent, even though Thutmose II’s mother, Mutnofret, was a perfectly valid candidate. We don’t know about the intrigue behind this move, but there must have been some.

Quickly after this, Hatshepsut and Thutmose would have been married. We don’t know exactly when it happened, but it seems that Hatshepsut, as the King’s and the King’s Great Wife’s daughter, the more well-educated of the two children, and already God’s Wife, was considered the more legitimate of them; she gave him legitimacy at a time when he sorely needed it. Though, again, he was about 9 years old, so it’s hard to say whether he even understood that he was in a precarious political position.

Despite the seeming significance of this marriage, there was no formal religious ceremony to mark Hatshepsut’s marriage to Thutmose II. Cooney writes, quote,

“the ancient Egyptians did not seem to celebrate marriage as we do. Rather than engage in a formal, binding relationship marked by ceremony, people merely talked about founding a household and drew up what amounted to the first prenuptial agreements in the world, legally documentaing whose property was whose. Marriage was more of an economic-sexual agreement in the ancient world than a romantic commitment.”17

The royalty didn’t even practice engagements—they were considered “premature and foolhardy” to get two young royals engaged before someone was seated on the throne.18 Hatshepsut had always been destined to marry the next king, whoever might hold that title. Unlike European nobility centuries later, who used young betrothals and marriages to cement diplomatic ties, the Egyptians had no need for such a practice at that time.

They of course consummated the marriage, though if they were 9 and 12 years old, it’s not hard to imagine they had no chance of conceiving. Some people estimate that they probably waited until they were older to marry, and that’s possible. Did they like each other, even love each other? We have no idea.

With Hatshepsut’s mother Ahmes as regent for Thutmose II and Hatshepsut as God’s Wife, the two women held enormous political sway. Technically the position as regent was an “informal post…a temporary stopgap with no official titles,” as Cooney writes, but practically Ahmes held a lot of power in the kingdom. One hint of how powerful they were lies in temples they created together—they did not give young Thutmose II all the power; quote, “they included their own images in teh new structures they created at Karnak Temple, an unprecedented move that hints at just how powerful they really were. On at least one of the surviving monuments, Thutmose II shares equal space with his Great Wife, Hatshepsut, and his mother-in-law, Ahmes.”19

Around this same time, Hatshepsut was displayed as standing alone before the god Amen-Re in his temple—it was probably the first time any King’s Wife was depicted with “such agency of her own, wholly removed from her husband.”20 She holds out an offering to the god, and her husband, who traditionally would be depicted as an intermediary, is nowhere to be found. This clear display of power, which was never damaged or destroyed deliberately, as many of her later images were, tells Egyptologists that Hatshepsut probably became something of a regent to Thutmose II as well; she ruled for him, using her own experience and self-confidence to sway him. More simply put, she overpowered the young king.

Unfortunately, we actually don’t know much about the day-to-day relationship between these three people—did they have a healthy and over-board relationship, the two women training the young king for his eventual role, or were there factions that they had to navigate and put down? The ancient Egyptians left us no evidence to formulate guesses.

Outside of them though, there were uprising. In Kush, in modern-day Sudan, there was an uprising that Ahmes put down brutally. She ordered that all the Kushite men be slaughtered, except for one son of the chieftain, who would live thenceforth in Egypt with the royal family. This may seem strange but it was a common pattern the ancient Egyptians used to create control over dominated regions; not only did holding a son hostage make a parent behave, but treating the son well usually made him loyal to Egypt and a good governor when he was sent back to his homeland as an adult. Ahmes’s husband Thutmose I had done the same as he conquered lands.

Around this time, a new person entered the picture out of truly nowhere. His name was Senenmut. How they met is unclear, but Hatshepsut and Ahmes turned to him when they needed a new kind of role to support them. They had their usual nobles supporting them, but their building plans and war plans would have normally required a man to be the campaigner for their work; they needed a man’s help raising money and leading soldiers.

Senenmut is interesting to us because he had absolutely no prior connections to the palace or even any noble families in Egypt before suddenly ascending to very high roles in the administration of Egypt. He was a nobody, but he was soon running their Great Hall, Overseer of the Two Granaries of Amen, and steward of both the king’s palace and the queen’s palace.21 None of these are small appointments, and all of them would have given him more political and economic authority. He may not have had all the privileges of education of upper-class Egyptians at the time, but he must have been more ambitious than all of them combined. Later, he would go on to become the Overseer of Royal Works, and he would use this access to commission statues of himself either in temple spaces or depicting his close relationship with Hatshepsut; one even shows him holding a complex cryptogram of Hatshepsut’s throne name, Maatkare. This statue is also famous because it is an innovation on a traditional form of Egyptian statuary; Senenmut often encouraged artistic innovation with his wealth, which is really interesting. I’ve included a photo of the statue I’m talking about in the Substack.

A lot of people suppose that, at some point, Senenmut and Hatshepsut became lovers. His statuary is so linked to hers, and one of his two tombs is near hers; it was audacious for him to have two tombs at all, but to put one near his queen is a big deal. But I don’t know, I don’t love this theory. It’s a super popular theory but to me, it sounds like part of the effort to discredit Hatshepsut. As we’ll see, that was a big theme after she died. The only evidence of this affair is that his tomb is near her and their images are often placed together—by him. She probably approved these images, but it doesn’t seem like she was commissioning them. To me, that sounds like someone who was an extremely loyal servant but who had no noble authority or reputation to stand on alone. He used building projects and artwork to trumpet his importance so no one could question it. But, and I know I sound like a broken record here, ancient Egyptians tended to not record court intrigue and things, so it’s certainly possible that this theory is correct and no one wrote it down.

That said, it wouldn’t have been a problem for her to take on a lover later in life. Spoiler alert, but her husband dies young, and Egyptian culture didn’t have strict control over sexuality like we have seen around the world over the last couple of centuries; Cooney writes, quote, “one highborn widow’s sexuality was probably not monitored or judged…Hatshepsut had no master. We should not assume her to have been chaste and nun-like… Indeed it is quite likely that Hatshepsut had lovers, affairs, trysts,” but Senenmut would not have been her only option.22 So yeah, maybe she did fall in love with Senenmut, but she could have had relationships with any number of people, male or female, and it wouldn’t have been an issue once her husband was dead. But I digress.

At some point, Hatshepsut gave birth to a daughter she named Nefrure, the Beauty of Re. She may have only been 14 or 15 at the time; quite young by our standards but an adult queen for the Egyptians. Senenmut became Nefrure’s tutor, on top of all his other duties. Considering his humble origins this is really astounding, but Cooney supposes that he was chosen because he wouldn’t have had any familial connections tying him to political factions. For the same reason that he was a trusted advisor to Ahmes and Hatshepsut, he was trusted with Nefrure.

Like his statuary dedicated to Hatshepsut, Senenmut commissioned statues showing his relationship with the princess. He commissioned at least ten of them, which would be very expensive, and all of them are very sweet—he either cradles her in his cloak, with just her baby head poking out, or she sits on his lap like a crown prince. They’re cute, but they also display once again his closeness to this family, “he belonged to this inner sphere of power” and other Egyptian elites did not.23 An image of these very cute statues is also in the Substack.

I’m sure some people see these statues as more evidence of his affair with Hatshepsut. Some rumors even go so far as to claim Senenmut is Nefrure’s father; they see these artworks as too fatherly. Some claim Thutmose II was too sickly and weak and young to have fathered a child at this time. But honestly, I suspect that Hatshepsut’s tutor Senimen would have also commissioned statues displaying his relationship with Hatshepsut had he also had all the other incomes that Senenmut did; this tutor was just particularly wealthy at the time.

If Hatshepsut had any more children after Nefrure, they were probably stillborn or died extremely young because we have no evidence of them. According to Cooney, “the ancient Egyptian royal family never mentioned children in the monumental or historical record until they were a viable and useful part of their political society.”24 Honestly, this feels like the modern equivalent of keeping the kids off Instagram, except it’s not for privacy reasons.

And this became an issue but Thutmose II was clearly dying. He had always been sickly and weak, but it was clear he’d never rule Egypt on his own. They began to look to the next generation and found it lacking. He had managed to father only one known son with a woman named Isis—she named that child Thutmose as well. While normally the royal family would have waited longer to start talking about who would succeed the current king, the discussions began early and urgently.

Meanwhile, Hatshepsut found herself in the middle of yet another succession crisis. Brilliantly, she began spreading the tale of something that happened happened to her when she was just a little girl at a festival for Amen. She says that at that feast, when the oracle was brought out for the king to consult, the god revealed himself directly to her instead, instead of the king. Everyone became concerned when he didn’t appear where he was supposed to, but then the statue moved toward her, crossing a wild pattern to find the young girl and told her that she would rule, that she was destined for it.

Many details are vague—how old was she when this happened? Who ruled—her father or her brother? Did the priests carrying the oracle and the king and Hatshepsut all really believe what as happening, or was it a stunt she planned in advance that the priests were happy to go along with the keep her generous role in their temple in place?25

The divine revelation was the first of many and would serve as the basis of Hatshepsut’s power. Importantly, it stripped her of any unseemly ambition and made her role nothing short of divine revelation. It was a heady story, and she’d need it to prop up her own rule.

Because soon, Thutmose II died at just twelve years old. He had reigned—with help—for just three years. Thutmose III became the next king—but he was two years old, at most. He needed a regent. With the heir a mere toddler, the biggest threat to Hatshepsut at that moment was the nobles who would be willing to ignore a living heir in order to put forth adult contenders, men with distant relationships to Amenhotep I or maybe even Thutmose I. Hatshepsut probably created a theatrical oracular experience, much like the one she had claimed to experience as a child, in which their god Amen picked Thutmose III out of a room full of possible heirs.26

Thutmose III’s mother, Isis, was a low-born woman, one of the wives brought in based solely on looks, not family lineage. So she was not considered a real possibility for regent—Hatshepsut managed to step in. The priests, bureaucracy, and military would have all had to agree to this, so it seems that they all “welcomed the rule of this young queen” because no serious fight about it was recorded in history.27 Ultimately, Thutmose III’s existence cemented the line of succession, but Hatshepsut had ruled for his father before him, so allowing her to continue ruling was probably like maintaining the status quo.

It’s worth noting that by this point, young kings with female regents were so common that women had ruled Egypt “informally and unrecognized for almost half o the seventy years before the reign of Thutmose III, an astounding feat given Egypt’s patriarchal systems of power.”28

So with Hatshepsut controlling Egypt, Thutmose began to grow up. And it’s this period of her life that she’s really most remembered for—and was most reviled for, at least for a while. She ensured that he was educated and made ready for rule, and Cooney suspects that he probably never saw her as an adversary or dominating, at least not during his childhood.

Now just about 17 years old, Hatshepsut maintained her role as God’s Wife, an unprecedented thing for her to do while also being regent. She was probably training Nefrure to take over as well, but her daughter couldn’t have been more than 3 at the time. It seems she did transfer the position to her daughter a few years later, when Nefrure was around 9 years old. Young, but with guidance it was possible for her to maintain it.

To consolidate her own power and Thutmose III’s, she began renewing temples throughout Egypt and Nubia. She exacted a monumental building project not unlike what her mother had done for Hatshepsut and Thutmose II. But Hatshepsut went even further than her mother had, claiming more and more space for herself in the temples she built on Thutmose III’s behalf.29 The next five years passed like this—she met with officials, trained her daughter, and enacted military campaigns. Her early projects were a neverending list of, quote, “construction, job creating, and income for priests and temple bureaucrats that had never been seen before in Egypt.”30 In fact, she was, quote, “instrumental in professionalizing Egypt’s religious arm.”31 Her regency was probably very popular among the religious and regular people who had steady incomes from her many extensive building projects.

But she had her sights set higher. She didn’t attempt a coup, she didn’t try to play sides against each other to weaken anyone—she was, quote, “practical and elegant, not devious and cunning. She was intelligently ambitious.”32 And we see this in the way depictions of her started to change.

Early statuary from her reign shows her in queen’s garb—the dress, the wig, the circlet. She is a slight woman, with delicate shoulders and a feminine face.

Soon though, as early as year 2 of Thutmose III’s reign, reliefs continued to show her in the company of the gods, still acting without a king as an intermediary but with the new addition of masculine descriptions. It’s subtle, but she’s showing herself performing the role of kingship.

Around the same time, Hatshepsut also ordered two obelisks for Karnak Temple, which Senenmut had carved with long-winded praise for her. Buried in it is the phrase, “the one to whom Re has given the kingship in truth…King’s Daughter, King’s Sister, God’s Wife, Great King’s Wife […] Hatshepsut, may she live…”33 This is a clear escalation in her claims to the throne. It doesn’t crown her or call her a king yet, but to anyone educated enough to read, this would have been interesting. To normal people, however, they would have just seen the familiar image of their dowager queen regent.

But that image started to change. She slowly became more androgynous in her depictions. The craftsman creating reliefs began to widen her shoulders and, quote, “extended the stance of her legs, even in figures wearing a queen’s long dress, to give her the active pose of a king striding forth.”34 She still retained feminine facial features and breasts in depictions, but not for much longer. Eventually, she entirely adopted the costume of the king, displaying herself without a shirt wearing a short masculine kilt and a kingly headscarf.35 She relied on the mythology of Amen for this more flexible approach to gender; in some texts, he was described as both father and mother, with a female manifestation of himself called Amenet. Hatshepsut adopted that androgyny for herself in art, but most Egyptologists doubt she actually dressed this way in real life.36

She also began to take on the phrase King’s Eldest Daughter, sort of implying that she should have been the rightful heir to her father’s throne all along.37 Next, another block from Karnak Temple shows her wearing a queen’s gown but also wearing the king’s crown, which is incredibly recognizable today and would have been then. The same relief also uses her throne name, Maatkare—but a throne name was something only male kings had ever had before. Strangely, her throne name shows up on other undated works of art, but occasionally out of the correct order; perhaps it’s a sign that she was touching up her monuments to include her throne name after they were technically finished.38 The block at Karnak Temple had been commissioned around year 5 of Thutmose III’s reign and it would have been finished two years later, just in time for her most audacious move yet.

In year seven of Thutmose III’s reign, Hatshepsut was crowned as king. She had edged her way there slowly, claiming royal responsibilities as they came up, until suddenly she declared herself co-regent, equal to Thutmose III.

Her coronation was, quote, “an expensive and overwrought affair memorializing the power that she had already amassed.”39 Another Egyptologist, Peter F. Dorman, described it as, quote, “the day on which her de jure iconography caught up with her de facto authority.”40 She probably went through a ritual other kings had gone through: She spent days and nights at the temple, consuming intoxicating substances, depriving herself of sleep or food, and chanting an praying in order to access the god Amen’s thoughts.41 Then she would have appeared before her people seemingly transformed, where she would be crowned and handed the crook and scepter that were the instruments of Egyptian kingship.

Hatshepsut recorded the awed reactions of witnesses. Quote, “Then these officials, their hearts began to forget; their faces astounded indeed at events. Their limbs united with fatigue. They saw the enduring king and what the Lord-of-All himself had done. They placed themselves on their bellies. After this, their hearts recovered. Then the majesty of the Lord-of-All fixed the titualary of her majesty as beneficent king in the midst of Egypt.”42

At this moment, she became King Hatshepsut. Unlike in European royalty, where we have Queen Consorts and Queen Regnants, which delineate whether the woman was the wife of the ruler or actually held ruling power, the ancient Egyptians didn’t have a word for queen, hence the title King’s Great Wife. Hatshepsut wasn’t Queen, she was just King of Egypt.

Hatshepsut received her other three throne names at this time. She had already begun using Maatkare, which seems to mean “the Soul of Re Is Ma’at.”43 If so, she was deliberately incorporating the feminine entity Ma’at, implying that the sun god’s power came from the goddess. Her other throne names do the same thing. Wadjyt-renput, meaning Prosperious of Years, not only implies that everyone will be rich during her reign, but it also incorporated the name of the cobra goddess Wadjyt. Similarly, her Golden Horus name, Netjeret-khau, meaning Divine of Appearances, combines female divinity netjeret with the masculine regeneration present with khau.44 Basically, her names wisely combined masculine and female elements, as if she herself embodied both the masculine and the feminine. It was a powerful theological argument for her reign.

Of course, before we forget, there was already a king. She became a co-king, and it was a strange move for her to declare herself the elder co-king well into the young king’s life. There had been co-rulers in Egypt’s history before, but usually it was an elder man splitting the role with his heir in order to help train him for the job. Never before had the younger ruler come first, only to have his reign invaded by an older regent.45

To help smooth this strange transition, Hatshepsut had his throne name altered from Menkheperre to Menkheperkare, which changes the translation from “the Manifestation of Re is Enduring” to “the Manifestation fo the Soul of Re is Enduring.”46 Basically, it moved Thutmose III one step away from the actual embodiment of the god that the pharaoh was supposed to represent. He was only ten at most at this point, probably even younger, so he may not have fully understood what was happening. But he couldn’t have missed that his stepmother now sat on a throne as high as his, nor that she wore the same crown as him when they were in public.

As her first order of business as king, Hatshepsut began another round of temple improvements, focusing on Egypt’s goddesses. She continued her father’s plan of replacing mudbrick buildings with stone ones and, quote, “essentially turned Thebes into one giant stone ritual space stamped repeatedly with her names and imagery.”47 Cooney supposes she focused on goddesses during this early effort because, quote, “believing that her power stemmed from the divine feminine, capable of both great destruction and soft tenderness, she embellished the temples of these goddesses, rebuilding those in ruin, and even elevating some divinities to a higher level.”48

But that doesn’t mean she was done with Amen, the god she had once been the wife of. If anything, early in her reign Amen became even more important to her. His name means “hidden one,” and ancient Egyptians believed that his true nature was often concealed; Hatshepsut leaned on this to claim that her own true nature as king has also been concealed, revealed to them only when the gods believed the time was right.49

While there was probably some pushback—this was all well outside the norm of Ancient Egyptian society—King Hatshepsut was not without precedent. She was probably aware of a woman named Sobeknefru, another female sovereign of Egypt only a hundred years earlier. She would have faced the most concerning pushback from the priests, since political power and religious power were so linked in Egypt at this time, but Sobeknefru would have been proof that the gods could welcome a female ruler.

But there’s evidence that she had to do some serious convincing outside the religious circles as well. Her temple at Deir el-Bahri is repeatedly carved with the line, quote, “he who shall do her homage shall live, he who shall speak evil in blasphemy of her Majesty shall die,” suggesting that this was a punishment that had to be enacted at some point.50 It was probably only more powerful nobles, maybe ones ambitious for power themselves who might have fought her; anyone else would have felt that it was, quote, “not their place to question their superiors, let alone their gods.”51

Nevertheless, there is, quote, “absolutely no evidence of insurrection, rebellion, or coup during her reign.”52 For most people, Hatshepsut was as mysterious, beautiful, and untouchable as any other ruler had been.

However, there is some evidence that Hatshepsut herself might have intended to push Thutmose III off his throne completely. In part of Karnak Temple, Thutmose III’s name was replaced with his father’s after Hatshepsut became king. The erasure might indicate something sinister was planned, but Hatshepsut seems to have changed her mind, replacing him back on temple reliefs. For the illiterate nothing would have seemed amiss, but for us it’s an intriguing clue. What was her plan, and what stopped her?

Regardless of her personal feelings, Hatshepsut and her co-ruler performed their role together. There were many rituals that required both of them anyway, or a King and a King’s Wife, which Thutmose III didn’t have yet. It was expected, of course, that he’d eventually marry Nefrure, Hatshepsut’s daughter.

But he was still not ruling. So it was Hatshepsut alone who decided to send men to, quote, “the uncharted south on a dangerous expedition…through the bone-dry Wadi Hammamat, 120 miles to the Red Sea, [then] a perilous sea journey of as many as 1,000 miles—an ancient Egyptian version of a voyage to the New World.”53 Their mission was to, quote, “search out the ways to Punt. Open the roads to the terrace of myrrh. Lead the army at sea and on land […] to bring the miracles from God’s country to this god, who created her beauty.”54

This seemingly semi-mythical land was probably near modern-day Somalia, Djibouti, or Eritrea. It was a major trading hub—maybe the first international trading hub—but it was also the only place where Egyptians could get myrrh, an incense that was incredibly important to their religious ceremonies. According to an article from New Scientist, “In Punt, the Egyptians could trade their grain, linen and other goods for aromatics, hardwoods and all manner of exotic products” like jewels, spices, incense, ivory, and rare animals.55

Until Hatshepsut, only kings who were, quote, “thought to be blessed by the dogs with good fortune and solid leadership skills” had successfully sent expeditions to Punt. So this was sort of a test in a way. And it paid off. The expedition returned in year 9 with cargo holds bursting with incense, ebony, and even incense trees so they could try to create myrrh with the tree sap themselves.56

It was a hugely legitimizing moment for Hatshepsut. It put her in the ranks of Egypt’s best kings to date. She ordered images of the triumphant landing carved into her incredible temple at Djeser Djeseru. This also set the tone for the rest of her reign—peace and prosperity.

In fact, of all her accomplishments, some argue that her expedition to Punt was, quote, “certainly the accomplishment she was most proud of,” though it seems that all of her trade initiatives were successful.57 She included an entire colonnade about it on her mortuary temple though, so it must have meant a lot to her.

Hatshepsut had probably been planning her funeral temple since before her husband’s death. She had taken it upon herself to finish whatever remained unfinished of Thutmose II’s and was actively building an incredible temple for herself. Today it is still considered one of the most impressive ones ever built.

The temple at Deir el-Bahri was modeled after the mortuary temple of Mentuhotep II, one of the great kings of Egypt who was revered by his descendants. It was, quote, “designed to blend organically with the surrounding landscape and the towering cliffs.”58 It is, quote, “unmistakable—instantly unique, somehow modern and ancient at the same time.”59 It featured a tiered three-layer temple fronted by colonnades and statues of Hatshepsut as the god Osiris—though it’s the more masculinized image of her that we get there. She called the temple Djeser Djeseru, meaning “Holy of Holies,” intended to link her kingship with the sacred and divine forever.60

It’s unclear who designed the temple, but Hatshepsut hired Senenmut to oversee it being built. And here’s where his expertise in artistic innovation and love of statuary came in handy. The temple is described as—and this is a longer quote, sorry:

The first, second, and third levels of the temple all featured colonnade and elaborate reliefs, paintings, and statuary. The second courtyard would house the tomb of Senenmut to the right of the ramp leading up to the third level; an appropriately opulent tomb placed beneath the second courtyard with no outward features in order to preserve symmetry. All three levels exemplified the traditional Egyptian value of symmetry and, as there was no structure to the left of the ramp, there could be no apparent tomb on its right. On the right side of the ramp leading to the third level was the Birth Colonnade, and on the left the Punt Colonnade. The Birth Colonnade told the story of Hatshepsut's divine creation with Amun as her true father.61

This story of Amun being her “real” father instead of Thutmose I is interesting. Earlier in her reign, she had relied on her link to him to declare herself a rightful ruler; now she was skipping him altogether, claiming divine birth. The inscription goes, quote,

He [Amun] in the incarnation of the Majesty of her husband, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt [Thutmose I] found her sleeping in the beauty of her palace. She awoke at the divine fragrance and turned towards his Majesty. He went to her immediately, he was aroused by her, and he imposed his desire upon her. He allowed her to see him in his form of a god and she rejoiced at the sight of his beauty after he had come before her. His love passed into her body. The palace was flooded with divine fragrance.62

In addition to incredible building complexes, royal expenditures on celebratory religious festivals exploded during Hatshepsut’s reign. Arguably this was a necessary part of her role—she was bringing the gods more clearly into everyday life to ensure their happiness. Unhappy gods result in bad flooding, poor harvests, droughts, and disease. But, more than that, Hatshepsut had probably hit on the idea that happy people don’t revolt against their leaders. 1500 years later, the Romans would call it bread and circuses.

When Thutmose III was around 14, he probably finally married Nefrure. He also had other wives, some of whom were probably getting pregnant—he was proving to be much more healthy and vigorous than his father had been. In addition to marriage and fathering children, he almost certainly went on military campaigns, becoming a strong warrior-king in the eyes of his people.

Hatshepsut’s reign was known for its peace and prosperity, but that doesn’t mean she was soft on enemies. She continued her father’s subjugation of Nubia to the south, and she maintained the tribute payments that Thutmose I had begun receiving from Syria-Palestine in the north. But she was more concerned with trade, resorting to military measures only when she had to rather than seeking to conquer new lands for the sake of doing it.

It was around this time, as Thutmose III was entering his late teens, that historians start to see a new word for palace, per-aa (which means literally great house, aka palace) associated with kingly authority.63 It seems that people weren’t always sure which king was dictating what, so stating that messages or orderers came simply from “the palace” avoided that awkwardness. It was a way to create a united front at a moment when there may not have been. But per-aa eventually made its way into the Bible as “pharaoh” and it’s where we get the term from.64 Hatshepsut would not have used the word pharaoh to describe herself, and neither would any other ruler of Egypt during this time.

Meanwhile, Hatshepsut was beginning to plan for the eventuality that she wouldn’t be co-king forever. She was probably planning to hold onto the role until she died, but she also began setting up Nefrure to take on a similar role. She seems to have wanted to set up Nerfrure as the next heir, to rule alongside Thutmose III. Was Hatshepsut thinking about transforming Egypt from a patrilineal ruling line to a matrilineal one? If so, this was her big attempt. She inscribed a stela for Nefrure with the phrases, “‘Mistress of the Two Lands’ and ‘Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt’—titles used by the female king Hatshepsut herself.”65 For a while, Nefrure abounded in the building projects and artwork Hatshepsut commissioned. She was everywhere. And then, just as suddenly, she was gone.

Nefrure’s name was then erased on all those reliefs and changed to Ahmes, Hatshepsut’s mother, who had died a while before.66 She was probably bowing to political pressure from nobles and maybe even Thutmose III. It seems like they had made an exception for Hatshepsut, but they weren’t willing to make the same one again.

Or, maybe Nefrure just died, dashing her hopes for some great mother-daughter passing of the crook and scepter.

We’re now in the last years of Hatshepsut’s life and reign. There seems to have been some kind of tension beginning to boil—perhaps people were restless with the co-kings situation. Thutmose III was healthy, robust, and by all accounts intelligent. Egyptian kings had no concept of abdication, but some ancient Egyptians might have accepted Hatshepsut's resignation.67 A new thing for her to try and invent.

Instead, Hatshepsut died in 1458. She was probably less than 40 years old. She had already ordered a sarcophagus for her own internment alongside her father, Thutmose I, and a near-duplicate sarcophagus was ordered for Senenmut. Her father had hit upon the idea of burying the pharaoh’s body in a secret cliffside tomb separate from his funerary temple—today we call that place the Valley of the Kings.68 Her temple remained unfinished at her demise but that shouldn’t cause us concern—traditionally, quote, “when a monarch died, the next kin typically did little more than ensure that the previous king’s sepulcher was capable of housing a body—any other outstanding details were left unfinished… Egyptians were not troubled by the idea of burying a king in an incomplete tomb—that was the last guy’s problem.”69 She was given the usual treatment of mummification for royals, laid to rest with a grand ceremony that lasted weeks, and then Thutmose III moved on, as he had to.

Some Egyptologists whisper that Hatshepsut was, quote, “helped to a premature end” over her disastrous efforts to make Nefrure inherit her throne.70 The truth is that we just don’t know how she died. If the mummy identified as Hatshepsut in 2007 is really her, then she was a bit obese and definitely diabetic by the end of her reign; certainly, untreated diabetes could have led to her demise.71 But this mummy has not been definitively identified as Hatshepsut.

Nevertheless, she was given all the honors of a reigning king at death. One of Thutmose III’s first acts was to finish a chapel Hatshepsut had been building and he monumentalized her in it rather than take all the credit.72 Some historians suggest that he actually kept calling back to her in his own statuary for a while after her death because he was insecure as a king and thought he needed her imagery to support his kingship. This seems unlikely since the second thing he did was a massive invasion of Syria; hardly an easy thing for an insecure king to accomplish.

For about five years, Thutmose didn’t do anything to destroy Hatshepsut’s image; a lot of people tell the story as if he immediately set about destroying her image as soon as she’d gasped her last breath. He didn’t at first but, at some point, her legacy as a female king became an issue and we’re not totally sure why. But just five years not his solo reign, the very chapel Thutmose had finished he ordered dismantled, the imagery of Hatshepsut as king strewn about to be subject to the elements. He never commissioned another monument, text, or statue that mentioned Hatshepsut again.

Why the change of heart?

Well, he may have been ashamed that his kingship was, quote, “sullied by a woman and that he had been weak.”73 But it also may have been a more pragmatic decision, rather than an ego-driven one. Maybe other people, like Nefrure, were asserting themselves, trying to claim power as Hatshepsut had, and he wanted to put a stop to that.74

This second idea seems more likely because he also made moves to weaken the role of God’s Wife of Amen, which had been the theological basis of all of Hatshepsut’s power.75 He also erased Nefrure’s name off his own temples and downplayed a wife’s lineage. From then on, only the father would matter when it came to deciding on an heir.

Cooney suggests that there were some problems of legitimization that he might have been facing. He might have thought that it was his quote-unquote “low-born mother” who had allowed Hatshepsut to take more control; maybe he needed to further legitimate himself so that he could also legitimize his offspring so they could be seen as viable kings no matter who their mother was.

To further distance himself, Thutmose gave his royal portrait a makeover; it had been the same for a long time, an image controlled by Hatshepsut. It was certainly time for a change. He started constructing new temples, including a funerary temple for himself.

But all this wasn’t enough. He began a systematic attempt to destroy images of Hatshepsut around year 43 of his reign. This was a big deal—for the ancient Egyptians, “violence against the images of the dead—particularly in a tomb context—was not just a defacement of the deceased memory but action meant to harm the spirit for eternity in the afterlife.”76 But Thutmose was fast approaching fifty, and he might have started to worry about his succession.

Twenty-five years after she died, Thutmose III set about systematically destroying any image of Hatshepsut and erasing her name from every wall he could find. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of reliefs, statues, and other images of Hatshepsut were attacked and replaced with images of his father or grandfather. Some just were left as blank caverns in the wall, creepy because they seem almost ghostlike—she’s there, but not.

He never explained why he did this, but the fact that only images of Hatshepsut as king were impacted seems to say a lot of what he was thinking. Images of her as King’s Wife, as God’s Wife were totally fine and remained untouched. It was that final step, proclaiming herself King, that he couldn’t have again for his sons. He did not want people seeing her specifically that way.

Cooney points out, and I think this is important, that waiting 25 years meant that Thutmose waited almost an entire lifetime before he attacked monuments to Hatshepsut. The average Egptian only lived to the thirty at this time! So something major must have shifted in the political landscape for him to suddenly take this defacement project on at the end of his life.

He tried this for four or so years, but Thutmose eventually gave up—it was a huge waste of time and resources to hire people to destroy perfectly good reliefs, especially when they weren’t also replacing any of those details. They were just scarring these walls. It probably was an insult to the gods to do such a thing.

Nevertheless, Thutmose’s eradication of her image was so thorough that she was largely forgotten until the nineteenth century. It’s been only recently that she has been rediscovered for us to learn about. Now she is remembered as one of the best rulers Egypt ever had.

That is the story of Hatshepsut! I hope you enjoyed this episode. You can let me know your thoughts on Substack, Twitter, and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks discover the podcast.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Clark. My research assistant is Niko Angell-Gargiulo. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com If you’d like to send us something, you can send it to P.O. Box 27162 Los Angeles CA 90027.

Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

“Brooklyn Museum.” Accessed October 11, 2023. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/3759.

Cooney, Kara. The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt. Kindle. Crown, 2014.

Dorman, Peter F. “The Early Reign of Thutmose III: An Unorthodox Mantle of Coregency,” 39–68. Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA: University of Michigan Press, 2006.

Google Docs. “Hatshepsut_From_Queen_to_Pharaoh.Pdf.” Accessed October 11, 2023. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cINK1qj7Y8Q1pvCoWeiHPN2295AiTUq_/view?usp=embed_facebook.

Karev, Ella. “Ancient Egyptian Slavery.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Slavery throughout History, edited by Damian A. Pargas and Juliane Schiel, 41–66. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13260-5_3.

Magazine, Smithsonian. “Egyptian Mummy Identified as Legendary Hatshepsut.” Smithsonian Magazine, June 29, 2007. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/egyptian-mummy-identified-as-legendary-hatshepsut-180940772/.

Mark, Joshua J. “The Temple of Hatshepsut.” World History Encyclopedia. Accessed October 8, 2023. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1100/the-temple-of-hatshepsut/.

RoyaltyNow. “Hatshepsut.” Accessed October 8, 2023. https://www.royaltynowstudios.com/blog/blog-post-title-two-egyff-t7etc-j2k9t-ylc3a-ddwmj-2yssp-9e7lc-b9sdj-y22wb-33syf-r236p-8fb2b-77s6p-zk48c-ddfdz-4xkyt-33khr-plrsw-wl4m6.

“We Have Finally Found the Land of Punt, Where Pharaohs Got Their Gifts | New Scientist.” Accessed October 11, 2023. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg25634170-800-we-have-finally-found-the-land-of-punt-where-pharaohs-got-their-gifts/.

Cooney, 9

Cooney, 10

Cooney, 10

Cooney, 15

Cooney, 22

Cooney, 12

Cooney, 27

Cooney, 26

Cooney, 40

Cooney, 37

Cooney, 37

Cooney, 38

Cooney, 47

Ella Karev, “Ancient Egyptian Slavery,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Global Slavery throughout History, ed. Damian A. Pargas and Juliane Schiel (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023), 41–66, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13260-5_3.

Cooney, 52

Cooney, 53

Cooney, 22

Cooney, 45

Cooney, 62

Cooney, 62

Cooney, 64

Cooney, 86

Cooney, 67

Cooney, 68

Cooney, 73

Cooney, 77

Cooney, 78

Cooney, 79

Cooney, 85

Cooney, 89

Cooney, 95

Cooney, 89

Cooney, 101

Cooney, 154

Cooney, 154

Cooney, 154

Cooney, 102

Peter F. Dorman, “The Early Reign of Thutmose III: An Unorthodox Mantle of Coregency” (Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA: University of Michigan Press, 2006), 39–68.

Cooney, 100

Dorman, 53

Cooney, 104

Cooney, 104

Cooney, 107

Cooney, 107

Cooney, 129

Cooney, 114

Cooney, 147

Cooney, 116

Cooney, 117

Cooney, 123

Cooney, 123

Cooney, 124

Cooney, 132

Cooney, 132

“We Have Finally Found the Land of Punt, Where Pharaohs Got Their Gifts | New Scientist,” accessed October 11, 2023, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg25634170-800-we-have-finally-found-the-land-of-punt-where-pharaohs-got-their-gifts/.

Cooney, 132

Joshua J. Mark, “The Temple of Hatshepsut,” World History Encyclopedia, accessed October 8, 2023, https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1100/the-temple-of-hatshepsut/.

Mark

Cooney, 144

Cooney, 144

Mark

Mark

Cooney, 157

Cooney, 157

Cooney, 176

Cooney, 177

Cooney, 110

Cooney, 182

Cooney, 182

Cooney, 178

Smithsonian Magazine, “Egyptian Mummy Identified as Legendary Hatshepsut,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 29, 2007, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/egyptian-mummy-identified-as-legendary-hatshepsut-180940772/.

Cooney, 196

Cooney, 199

Cooney, 199

Cooney, 211

Cooney, 208