Welcome to the next episode of Unruly Figures—I’m really excited to be covering Yasuke, the first (known) Black samurai. His story tells us so much about feudal Japan and I think it’s a particularly fascinating story about how cultures collide and adapt to each other across time. Enjoy!

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m going to be covering Yasuke, an African man who made his way to Japan and carved out a fascinating life for himself there.

But before we jump into Yasuke’s life and how he became the first Black samurai, I want to give a huge thank you to all the paying subscribers on Substack who make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! Each of these episodes takes me nearly 30 hours of work, which means they’ve become a full-time job. So if you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber for just $6/month or $60/year! Contributions help ensure that I will be able to continue doing this work. Becoming a paying subscriber will also give you access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates on the upcoming Unruly Figures book. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

Okay, let’s hop in.

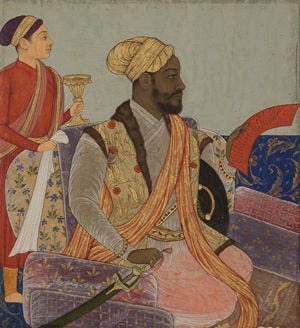

As with many of our pre-20th century figures, we don’t know much about Yasuke’s life before he entered the historical record for his daring deeds. Historians guess he was born in Ethiopia, Mozambique, or Nigeria, but that’s based mostly on where slaves were frequently being kidnapped from at that time, not any sort of hint about a language he spoke or people he identified with. His name is no hint either—it was bestowed upon him in Japan, when he was already in his mid-to-late twenties. What name he answered to before that seems to be lost to time, though some propose Yusefe as a birth name.1

We think he was in his mid-twenties in the late 1570s, putting his birth between 1550 and 1555. He grew up until his preteen years in an agrarian lifestyle; historian Thomas Lockley supposes in his biography African Samurai that Yasuke might have grown up tending to cows and may have been part of one of the many African groups that consider cows sacred. Lockley suggests the Dinka people of South Sudan as Yasuke’s original people, but he’s the only one to get so specific.2 The Dinka are also called the Jaang or Jieng.

We can guess that Yasuke was kidnapped from his home by slavers when he was about 11 or 12. This is mostly an educated guess—at this time, slavers killed adults, who were dangerous to the slavers, as well as children under 5 who required too much care to be trafficked. Very young children often died on the grueling journey to the coast to be shipped off into slavery, so Yasuke must have been among the older group. This kidnapping was certainly a terrifying and traumatizing event—it’s likely that his entire family was killed, and that he was beaten and tortured in addition to being forced to walk to the coast. It set in motion a very violent adulthood.

Attackers like the ones that kidnapped Yasuke were usually other African men, hired by the foreign seamen who would pay for the surviving children upon delivery, and then pack them into a ship. Yasuke was trafficked from his home to the eastern coast of Africa, bought probably by Indian, Arab, or Persian slavers, then put on a ship and taken to India, where he was sold in a slave market. The journey might have taken as long as a year.

In India, he became a mercenary or soldier, a military caste referred to as Habshi, the Arabic word adopted by Indians to describe specifically African people living in India.3 It’s estimated that, throughout history, as many as eleven million Africans were trafficked to India, mostly to be used as slave soldiers.4 Who Yasuke worked for is unknown, though Lockley suggests Ibrahim Husain Mirza, a Persian lord who had bought seven hundred African mercenaries to help him defend territory he owned in Gujarat.5 He would have spent a few years training to use weapons, ride horses, and fight. Enslaved soldiers weren’t usually treated as, quote, “mere fodder,” since they were expensive; they were trained, clothed, fed well, and eventually became effective soldiers.6

In fact, slavery in Asia at this time was a little different than the chattel slavery we’re more familiar with today. Though the beginning—the violence and trafficking—are the same, enslaved people often had a chance to buy their freedom or were freed when their enslavers died. They experienced, quote, “a degree of freedom” and were sometimes “adopted into the owner’s family or married to a family member. Some eventually became rich and respected members of their local communities.”7 We think this is probably what happened to Yasuke while he was in India.

Lockley proposes in his biography that Yasuke was present for the beginning of a significant battle in Gujarat on January 1573, when Akbar, a Mughal emperor arrived to consolidate the area into Mughal rule of northern India.8 Rather than risk complete slaughter, the commander at Surat, Hamzaban, surrendered to Akbar. What became of Ibrahim Husain Mirza is unclear, but I’m betting nothing good, since he’d been rebelling against Akbar by holding Gujarat. Regardless, Akbar allowed the African soldiers and Portuguese visitors to leave the region freely, but they only had one day; Lockley suggests that Yasuke joined a Portuguese crew as an oarsman and escaped to Goa, the Portuguese stronghold in India.9 He was a free man now.

By the way, I’m saying Lockley proposes or suggests a lot because a lot of his biography of Yasuke is educated guesses, or so it seems to me. There are few good records of enslaved people anywhere, and so we can’t be sure of exactly where in India or by whom Yasuke was enslaved. We know for sure that he was trafficked to India and that he became an experienced soldier before meeting his Portuguese employer who would take him on to Japan, where he would finally go down in recorded history. But that’s all as far as facts go; everything else has to be educated guesses, based on patterns that Lockley must see across this period of history.

And getting to Yasuke to Goa is necessary for the next part of the story. Because it was there that Yasuke almost certainly met the man whose life he’d guard for the next several years: Alessandro Valignano.

But first, Yasuke would spend a few years in Goa, probably working with the Portuguese Jesuits. He probably started working as a bodyguard and valet right away, and his job was considered high-status among the working classes.10 Serving a noble churchman would have brought Yasuke, quote, “considerable honor, and the opportunity for a comfortable living too.”11

How he met Valignano is unclear, but it was sometime between 1574 and 1578 that Yasuke met this important emissary from Rome. Valignano was a Jesuit missionary, traveling to supervise the introduction of Catholicism to Asia. At just 35 years old, Valignano had been appointed Visitor to the Province of India, a very prestigious appointment, especially for someone so young. In contrast to other Catholic missionaries, Valignano was good at integrating Catholicism with a country’s existing cultural norms. For instance, later on in Japan, he converted a traditional Japanese Shinto temple into a Catholic church, rather than destroying it and rebuilding it like most other Jesuits would have.12 While most other missionaries were hellbent on destroying quote-unquote “heretical” monuments, Valignano knew that you catch more flies with honey. This approach later was called adaptationism. And it worked! By compromising with local customs, Valignano was able to spread Catholicism with a lot less trauma and bloodshed than the methods others proposed.

Though, well—I’ll come back to the trauma and bloodshed.

It’s worth noting that Valignano did this to, quote, “gain the respect of the people whose souls they strived to save.”13 And it led to some of the earliest European documentation of Asia. For instance, Valignano established the earliest “European scholarship on China when he ordered that four scholars be assigned in Macao solely to the study of China and its literature.”14 Later, when he arrived in Japan, he, quote, “advocated imitating the ways of Buddhist priests and his leadership led eventually to the first Portuguese-Japanese dictionary, Japanese translations of European texts such as Aesop’s Fables, and Portuguese translations of Japanese tales such as The Tale of Genji.”15

So Valignano and Yasuke cross paths. By this point, Yasuke was probably a free man and Valignano hired him to be a bodyguard. There’s a chance that Yasuke was still being sold as a slave and Valignano paid for him and then freed him, but either way, Valignano would not have been walking around with an enslaved bodyguard. Valignano quote, “explicitly disapproved of slavery,” and as one of the most important representatives of Christendom in Asia at this time, he could hardly be seen walking around with, quote, “an actual symbol of either wealth or slavery,”16 two things the Jesuits condemned.

Valignano needed Yasuke because he knew he was on his way to Macau and then Japan, where his safety was very much in question. Japan was at the end of a hundred years of civil war, but the brutal fighting was far from over, and missionaries weren’t allowed to carry weapons themselves so he needed a bodyguard. And Yasuke, towering over most people in the 16th century at 6 feet 2 inches tall, was a great asset for intimidating people before they even tried anything.17

As a member of Valignano’s staff, Yasuke was, quote, “probably paid, and certainly well dressed, managed to receive some education, and was armed to the teeth with well-made weapons.”18 He was not just a bodyguard, he was an attendant, seeing to Valignano’s comforts as well as his physical. He was also something of an exotic item, something for Valignano to show off.

You see, there were very few Africans living in Japan at this point. And Yasuke’s arrival caused a sensation.

Yasuke arrived in Japan alongside Valignano in July 1579. They arrived bearing more than Bibles and the word of God: the Jesuits had established their foothold in Japan only thirty years before by selling Portuguese guns and cannons to the highest Japanese bidder. For the Jesuits, quote, “a few crates of firearms to save millions of souls was, in the end, a fair bargain.”19

They landed at Kuchinotsu, the political maneuvering already beginning before they’d even arrived in port. They were originally supposed to arrive in Nagasaki, but the local Jesuits living in Japan wanted to punish the Japanese lord who ruled Nagasaki by denying him the massive taxes he would have earned by hosting the Portuguese ship.20 Instead, a much younger and less powerful lord, Arima Harunobu, would receive the taxes and honor of welcoming the Visitor to Japan. Arima was a Catholic, at least in name, and was at war with Japanese lords to the north who detested the Catholic incursions into Japan.

When they made port Yasuke was probably wearing Portuguese clothes, supplied to him by the Jesuits. But everything else he carried were testaments to his worldliness—he carried, quote, “a tall spear from India, its blade crafted into an unusual wavy shape with two ‘blood grooves’ cut into the steel to make the blade lighter while still sturdy. He also carried a short Arab dagger at his side…his dark head was wrapped in a stark white turban—like cloth to protect it from the sun.”21 He would have appeared, clearly, like a well-traveled man.

Onshore waited a large welcome party—a combination of other Jesuit missionaries, Arima, his entourage, villagers, and merchants eager to trade. Lockley estimated “six or seven hundred…amid large tents pitched for the occasion and adorned with flapping banners sporting the symbol of the Arima clan.”22 They sang Te Deum Laudamus as the Visitor approached in a small boat, his bodyguard behind him.

Yasuke must have been slightly on edge. Valignano, as a powerful symbol of the Church, was a prime target for assassination. In Japan at this time, quote, “warriors were the pinnacles of society and virtually all men bore some kind of weapon in daily life,” meaning he was facing a well-armed crowd of strangers as they landed at Kuchinotso.23 But everything proceeded peacefully. The people were stunned by Yasuke, they stared at him with “evident awe;” not only were Black people rare in Japan, but Yasuke towered above the average height of Japanese people by more than a foot.24

At this time, especially in isolated regions, it was very possible that people had never seen anybody like him. Many wondered if he was, quote, “truly human or some form of god or devil.”25 And they meant that really in the best possible way—for the Japanese at this time, black skin would have been remarkable and entirely positive. The Buddha was sometimes portrayed as black-skinned, and Daikokuten, a Japanese manifestation of Shiva, the Indian deity of wealth and prosperity, was also usually portrayed with very dark skin.26

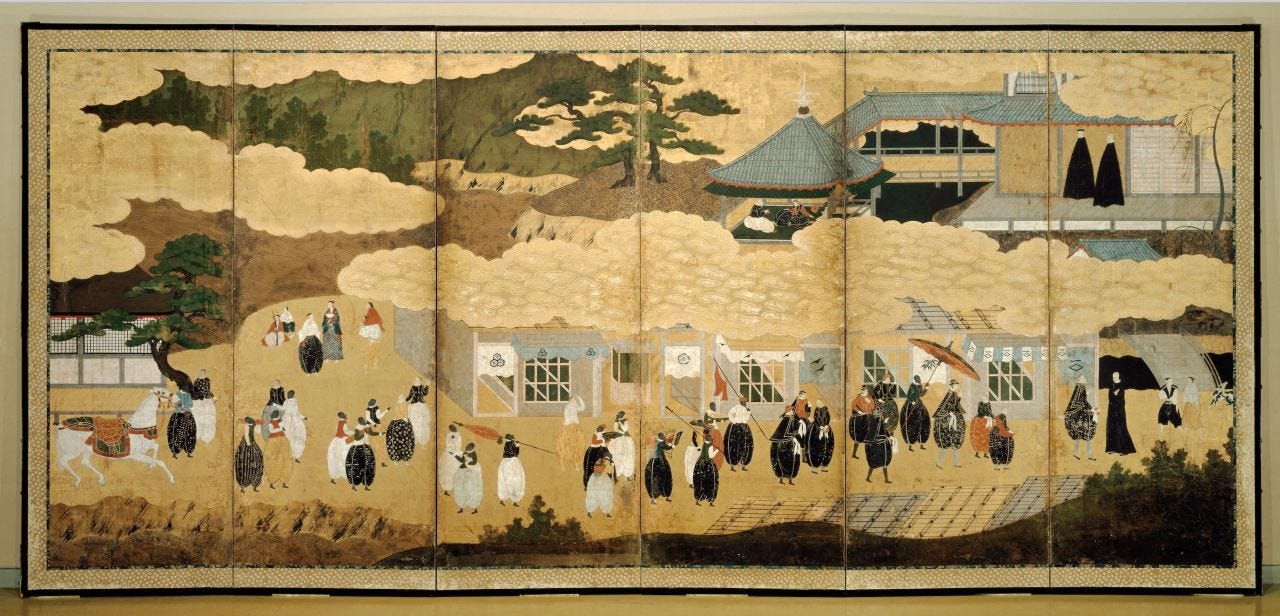

In Japanese art of the time, African characters are sometimes portrayed as sailors and servants to Europeans, but they are well-dressed, not poverty-striken or abused. But African characters are also portrayed as bodyguards like Yasuke, better dressed and holding weapons including a trident, which aligned these characters with Shiva as well.27 There are also portrayals of wealthy Black men in Japanese art, wearing, quote, “higher-quality dandified clothing and shoes characteristic of the wealthy Portuguese.”28 Africans were rare but became respected, even popular, in Japan during the 16th century. Some suggest that the modern problem of Japanese racism against Black people is really a product of 18th-century globalization, when Japan began adopting European attitudes toward other populations. Others suggest it began earlier, perhaps in the 17th century when the popularity of Christianity began to create negative views of Buddhism and the dark-skinned Buddha; again this is a European import.29 Regardless, Yasuke was viewed very positively by Japanese people when he arrived there in 1579.

However, there were multiple fronts of unrest in Japan when Yasuke landed. Their first host, Arima, was fighting a constant series of battles with the neighboring Ryūzōji clan, who were staunchly anti-Catholic. On the island of Honshu, the Jesuit patron Oda Nobunaga was consolidating power and suffered an embarrassing defeat at the hands of the shinobi, sometimes called ninja.30 Meanwhile, within the Japanese Catholic converts, which numbered around 100,000 by 1579, many were pushing to be full members of the Jesuits, but their low ranking was dictated by race alone.31 There was disagreement within the European Catholics about how to handle this, which Valignano would settle by opening three seminaries specifically aimed at training locally recruited Jesuit brothers and priests.32

Almost as soon as they landed in Japan, Valignano put his bodyguard to the test. Not content to remain in a fishing village, he wanted to go to Arima’s castle, which was at that time under siege by Lord Ryūzōji. They sneaked in by taking a sampan boat up the coast in the dead of night and then hiking up a mountainside through semitropical forests.33 Enemy soldiers almost certainly patrolled the forest, but they reached Hinoe Castle safely, and the fort was sturdy and defendable.

Yasuke stood guard as Arima and Valignano negotiated—their trade was Arima’s eternal soul for cannons, basically. Arima was already nominally a Catholic, but he had a way to go before being truly devout; for instance, he had a mistress that the Jesuits weren’t crazy about. His choices were to be monogamous, at least in word, or try to face Lord Ryūzōji without Portuguese weapons. Arima chose monogamy and the bride the Jesuits had picked out for him.34 Valignano ordered Arima two cannons from Portugal—they’re not explicitly a wedding gift, but it sure feels like it, doesn’t it?

Yasuke and Valignano remained with Arima for the next nine months, visiting villages, helping build a Catholic seminary, and shoring up converts. Yasuke focused on learning Japanese and quickly became conversational with locals.35 His day-to-day life was simple: He rose before dawn to patrol the seminary grounds; Arima had soldiers who were doing the same, but Yasuke would have done it himself as well. He would probably spend an hour or so per day exercising and training; he began learning how to use new Japanese swords at some point. He was also studying Japanese fighting styles, to learn how to fight if he ever came up against a Japanese attacker.36 If he hadn’t learned to wrestle by then, he definitely did in Japan; there is surviving artwork showing Yasuke participating in a sumo match. In addition to this, Yasuke would supervise the preparation of meals Valignano consumed, to make sure that he wasn’t poisoned; it’s unclear to me if Valignano also had a taster or if Yasuke also fulfilled that role. Otherwise, he was near Valignano, supervising meetings and study sessions to make sure no one attacked the man he had been hired to protect

Yasuke had plenty of time off—Valignano was known to be “fair with his subordinates,” and would have given Yasuke time to relax or take care of his own needs. Lockley guesses that Yasuke spent this downtime swimming, bonding with other soldiers or servants, and dating or visiting brothels.37 At this time, Japan had not fully absorbed Confucian ethics, and women were still equal to men, including being able to equally pursue their own enjoyment; sex, for the Japanese, was not restricted to marriage.38

At Christmas 1579, Yasuke performed in a nativity play as Balthazar, one of the magi who gave baby Jesus the present of myrrh. Balthazar is often portrayed as being African, so Yasuke was probably a shoo-in for the part, though he was probably anxious about acting while his charge was surrounded by strangers who had traveled for days to visit Arima’s seminary—who knew if an assassin hid among them? But, as usual, things were fine.

Throughout 1580, Yasuke accompanied Valignano on his many “frenetic” trips throughout the southern island of Kyushu, where he met with Christian lords and visited missionary outposts.39 They sailed almost everywhere, an easier way to travel than by road in the mountainous and rainy country. Also, they were surrounded on most sides by enemies; travel by boat was significantly safer.

Now, remember how I said that they were originally supposed to land in Nagasaki? They had been rerouted because the Jesuits were angry with the warlord whose territory included the larger port, Ōmura Sumitada. Ōmura had been, quote, “the first high-level Catholic convert in all of Japan and was, by all accounts sincere in his Christian faith.”40 But he had allowed his daughter to refuse to marry Arima, and the Jesuits were upset about it. To make it up to them, he offered them Nagasaki—the whole port and the lands around it, free to the Jesuits in perpetuity.41

Valignano and Yasuke moved to Nagasaki in the spring of 1580. It was, officially, the first Jesuit-controlled colony in Japan. Valignano immediately began working with engineers, sailors, and local merchants to expand on the existing “basic” infrastructure and build a defensible and well-armed seaport that would bring glory and riches to Japan—and, hopefully, make Japan Catholic.42 Within a year, the population of Nagasaki doubled—not just Japanese people, but Chinese, Europeans, Indians, Africans; Christian converts from all over Japan flocked to the port.43 New laws stated that only Catholics could live in Nagasaki.

In Nagasaki, Yasuke’s role changed a bit. The port city was relatively safe, so he was assigned to train a new militia, built out of the, quote, “ragged collection of refugees and masterless warriors, ronin, who’d recently embraced the Catholic cause” and arrived in Nagasaki.44

They remained in Nagasaki only until September 1580. They were, finally, on their way to Kyoto where, quote, “the most important souls in the Japanese world waited,” at least by Valignano’s measure.45 Though the emperor of Japan at the time held only symbolic power after a century of civil war, Valignano believed that if he could be converted, the rest of Japan was sure to follow. Additionally, Valignano wanted to meet and potentially convert Oda Nobunaga, who had been consolidating power across Honshu, the largest island of Japan. He was not the shogun, a title military ruler, but that was only because he himself had abolished the title in 1573.46

To get there, however, they had to cross the treacherous Seto Inland Sea, which separated the largest Japanese islands and was “entirely controlled by ruthless bands of pirates.”47 The pirates were multicultural, fearless, and innovative—only a few years earlier it had been a Seto pirate clan that had constructed the world’s first ironclad ship.48 But their reputation for immense violence had spread further, as far as Cambodia, well over 2,000 miles away, and the only way to get past them was to pay courtesy fees and turn the pirates into escorts. Valignano paid a high enough fee to buy an exceptionally powerful and well-armed escort: Lord Murakami of Noshima, the “most powerful of the pirate lords.”49

But even with the high fees paid, there were other threats while sailing in this sea. The Mori clan, based out of modern-day Yamaguchi, were violently anti-Jesuit, and could be expected to attack if they saw the Jesuits sailing by. So when they finally set sail in March 1581, Valignano and his entourage of three dozen Jesuits were forced to sail on a longer journey, one that avoided the Mori clan by island-hopping through rougher waters. The pirates were used to foreign guests on their ships and made the journey as comfortable as possible, hosting the Jesuits in forts and pirate bases at strategic points along the journey.50 Each night probably included music, dancing, and wine, but Yasuke wouldn’t have participated—pirates are pirates, after all, and he probably would have chosen to remain sober in case of treachery.

They soon arrived at Sakai, which Europeans called the Venice of Japan because of its “attractive settlement of rivers, canals, mercantile spirit and international trade.”51 They recovered overnight and the next morning set off on their long journey to Kyoto in a parade of humble wealth—there’s really no other way to describe it. They were dressed in, quote, “drab clothing” but also “made an effort to stand out.”52 But Valignano led the procession riding a horse and bearing a holy relic: a splinter from Christ’s cross in a jeweled casket. Maybe this is the 16th-century version of quiet luxury?

The procession was, as Lockley writes, “intended [as] one of the most peculiar and arresting things the locals had ever seen. In this war-ravaged age of disunity, Valignano’s process was an extreme spectacle and novelty for those they passed.”53 People of all classes traveled from miles around to see this—a true once-in-a-lifetime experience. Hundreds of people crammed into narrow streets to see the procession go by. It was a display of Catholic religiosity and splendor as well as humility and faith.

Things were going according to plan. Until they weren’t.

Sakai was a very commercial city, and so they had certainly seen people of different races before. However, according to Lockley, “in living memory, no African man such as Yasuke. The combination of his size and shade fascinated the crowd; the women were gasping and grabbing at him as he passed, the men pointing at his muscles and comparing them with their own.”54 The crowds clamored to see him, and word spread.

Now Yasuke was walking alongside Valignano, ready to defend his charge if necessary. But the crowd began to get out of control in an effort to reach him. Little scraps broke out as people pushed to see him, and they cut off the procession’s progress. The Takayama guards that were escorting them to Osaka tried pulling the horses through faster, but all that succeeded in doing was separating the mounted riders from the seventy or so porters and attendants who were walking—including Yasuke.55 Eventually, Yasuke commandeered a horse from a local guard and safely rode out, making it to Osaka by nightfall. It was not a good harbinger of what was to come though.

Throughout their procession to Kyoto, the experience repeated in every town. Lockley writes, quote, “[Witnesses] openly gaped at the African colossus. His presence possibly spoiled the effect of religious aw Valignano had hoped to promote. (Or again perhaps, Valignano knew exactly what he was doing.)”56

The day before they reached Kyoto, they were summoned to Oda Nobunaga’s presence “with all haste.”57 They had expected to have to wait in Kyoto to see the powerful Nobunaga for weeks or even months; to be told to hurry up was a huge honor and boded well for Valignano’s goal to get Nobunaga to convert—or so they thought.

They set off for Kyoto the next day at dawn. It was March 27, 1581. They were supposed to arrive around mid-day in what Lockley called a “well-planned Valignano production.”58 In addition to the 100 or so people intended to travel with the procession, it had gained hangers-on as they traveled; by the time they reached Kyoto that number had mushroomed to several hundred hangers-on. Which Valignano probably enjoyed—”engineering large crowds was an old Jesuit tactic to generate publicity and new followers.”59 But that day was very different.

Kyoto was already the most populous city in Japan, but tens of thousands of extra people were at that moment vacationing in the city for the upcoming umazoroe, a Cavalcade of Horses spectacle that Nobunaga had planned. They were ready for the festival, already drinking and searching for something fun to do when the procession arrived. Very few of these people had ever seen a European before, nor an African—Lockley notes that most of them probably didn’t know Africa existed at this point. That sounds unfair, but we’re talking about very isolated people in the 16th century; Europeans had only arrived in Japan thirty years before. This was a combustible combination.

Now, why Yasuke was not mounted on a horse while entering Kyoto is beyond me. You’d think that Valignano and the others would have learned. But he was walking, and almost as soon as they entered Kyoto it became a dangerous situation for him. The crowds, drunk on excitement and actual alcohol, not only wanted to see Yasuke—they wanted to touch him. Then they wanted a piece of him. Some began to “yank away a piece of clothing as he passed,” others “scratched his skin,” perhaps seeing if his dark skin was painted on.60 Some believed they were encountering the deity Daikokuten made manifest and wanted a piece of him. It quickly became a riot.

Yasuke had to run for his life. Through the streets of Kyoto, a city he’d never been to, he ran ahead of a mob; he was there to protect Valignano, but his charge was clearly in more danger from the mob trying to see Yasuke, so the soldier had to draw them away and try to survive it. The soldiers in procession with him tried to help as best they could, but soldiers, citizens, bystanders, and vendors were all, quote, “swept into the roiling human tsunami” that followed Yasuke across the city.61

He made it to Kyoto’s only Catholic mission—the roar of the riot probably alerting the church’s guards that something was afoot. It seems like Valignano and the others, who were mounted on horseback, arrived before Yasuke, because attendants from the church knew to expect him and barred the entry as soon as he was inside.

But there were no real fortifications to keep people out—the walls were only thin wood; it was a church, not a fort. The crowd outside threw rocks and rocked the walls, trying to get in. Other Jesuit missionaries of the time, including Father Luis Frois, wrote about listening to the mob outside, hearing “the sounds of people wounded by stones” as they were thrown to try to break down the walls.62 Only Yasuke was armed; the Jesuits were not allowed to carry weapons—so if the fortifications were broken, the entire group was in danger. Frois later joked in a letter back to Rome that, quote, “if we displayed the man, we could earn eight to ten thousand cruzados in a short time,” but at that moment Kyoto’s demand to see Yasuke probably didn’t seem so funny.63

Then suddenly, the crowd was moving away. They were driven away by calvary and foot soldiers sent by Lord Nobunaga, who had heard the commotion—it was hard to miss, apparently, even in a city as large as Kyoto. Once the crowd was cleared, the soldiers entered the church peacefully and made a strange request: Lord Nobunaga wanted to see “him.”64 Not Father Valignano, who he was supposed to be seeing, but Yasuke, the man who Kyoto had temporarily lost its mind over.

Yasuke proceeded alone, with only these new soldiers and the father of the Kyoto Church, Gnecchi Organtino, to Honnō-ji Temple, a Buddhist compound that Nobunaga had recently commandeered and refitted to his needs. Yasuke probably had no idea what to expect. Was Nobunaga furious, ready to punish—even kill?—the men who had disturbed Kyoto’s peace? He didn’t have to wait long to find out.

He entered the audience chamber and, quote, “immediately prostrated himself, bowing his head low to the floor.”65 Nobunaga observed him, quietly. He was one of the most powerful men in Japan, in control of the most important provinces around Kyoto; even the emperor afforded Nobunaga courtesy. The room was likewise silent, either stunned by Yasuke’s presence, or silent in respect of Nobunaga’s continued silence.

Eventually, he invited Yasuke and Father Organtino to approach. Organtino was close with Nobunaga and had met with him on several occasions, they were almost friends. He explained that Yasuke actually spoke Japanese, and Nobunaga engaged directly with him, grinning with delight when Yasuke actually responded in good Japanese.

The next part might make everyone uncomfortable, but I think it illustrates how truly new Yasuke seemed to people in Japan. Nobunaga invited Yasuke to stand so he could view the warrior up close; in perhaps amused disbelief of the color of Yasuke’s skin, he called for water and a brush to try to wash the black color off of his arm. Yasuke submitted to this examination, supposedly amused by Nobunaga’s amazement.

Again, dark skin was associated with deities at this time in Japan, so Nobunaga was probably not intentionally being disrespectful, but please don’t take a page out of his book and do this to anyone.

Nobunaga saw him as something of a “miracle” and decided they would immediately celebrate the arrival of Yasuke with a party.66 Yasuke, Organtino, and their guard Takayama were also very pleased by this because it was a good start for Valignano’s relationship with Nobunaga, even though Valignano wasn’t there. Yasuke became the evening’s main entertainment as they ate and drank; he was seated at the lord’s right hand and was quizzed about everything he could possibly tell Nobunaga—hunting, his birth country, weapons, how he liked Japanese food, Confucius—it was a truly wide-ranging conversation and the beginning of a significant friendship. At the end of the evening, Nobunaga gifted Yasuke ten strings of copper coins weighing eighty pounds—a small fortune.67

A few days later, Valignano finally met Nobunaga. So as to not distract proceedings, he left Yasuke behind—but ended up offering Yasuke to Nobunaga. He was planning to return to Goa, and from there, Europe, and wouldn’t need the services of a bodyguard anymore, but if Nobunaga wanted to hire Yasuke, he could. Nobunaga agreed, apparently delighted.68 I know this sort of makes it sound like Yasuke was still enslaved, but it should be viewed through the 16th-century standards of patronage; though Valignano didn’t own Yasuke, he was his employer and to some extent, finding Yasuke another job when Valignano no longer needed him was the honorable thing to do, rather than just turning Yasuke loose with no prospects for employment and therefore safety or security. Our modern practice of applying for jobs was not fully in effect, not in the same way.

After he moved to Nobunaga’s compound, Yasuke lodged in a small private residence meant for short-term guests. For at least a week, maybe longer, Yasuke waited for instructions, kneeling in a waiting room while Nobunaga finished preparations for the umazoroe, a Cavalcade of Horses spectacle. Though he knew it was an honor to be adopted into Nobunaga’s clan, something few foreigners had possibly ever achieved without marrying someone, he still had no idea what this role was to be.

Now might be a good time for a quick rundown on rank in 16th-century Japan. Technically the emperor was the divine sovereign, a hereditary role that ruled over a court of hereditary nobles. But real power in Japan was held by the samurai, the warrior class that had dominated since a civil war in 1185.69 A military dictatorship, called the shogunate, was in charge for a few centuries, but the last shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki, had been exiled by Nobunaga himself in 1573. Instead, military warlords called daimyō ruled over regional provinces and were constantly fighting for dominance. Each daimyō had several vassal samurai to whom he could dole out riches and land. Many vassal samurai had their own samurai vassals, who might have their own warriors reporting to them, and beneath the lowest-ranking warrior class were the farmers who rented the land and sold the products of their labor, their income trickling up. If the structure sounds similar to European feudal society… it was. Under this system, Nobunaga was the most powerful daimyō in Japan, shogun in all but name—since he’d abolished the title. He could command an estimated 200,000 samurai warriors, an astounding number at that time.70 This was the man that Yasuke now found himself reporting to.

At Nobunaga’s request, Yasuke rode in his column of retainers during the umazoroe, though he wasn’t part of the performance. He was part of the spectacle: This fascinating man from an unknown land, serving Nobunaga. It increased the daimyō’s power.

A few weeks later, in May 1581, Yasuke accompanied Nobunaga to his capital, Azuchi. Unlike Valignano, who Yasuke had always walked alongside, he was invited to ride next to Nobunaga. Not as an equal, exactly, but as a member of Nobunaga’s close circle of pages. They were mostly teenagers, the sons of his highest-ranking samurai, but they represented the future of his realm, so Nobunaga was careful to spend time with them, making sure they were well-trained and loyal to him.

Azuchi, it’s worth mentioning, would have seemed incredible to anyone who saw it. His palace basically was an entire mountain, with countless roads and buildings leading up to the peak, where Nobunaga’s seven-story donjon stood. The five lower floors of the keep were painted black, but the sixth was painted red and the top floor was painted with pure gold. It would have reflected the sun so much that it would have looked as if it were the sun, quote, “emanating glory over the surrounding world.”71 When they arrived in Azuchi, Yasuke was temporarily housed with the on-duty guards of the fortress, but his fortunes were about to change.

His job was similar to his work with Valignano—Yasuke was a bodyguard, but even more than that he was there to, quote, “impress, entertain and intimidate…Nobunaga wanted someone who would, by looking good, make him look good too.”72 When called upon, Yasuke could also entertain, and he was often at Nobunaga’s side, telling him of foreign lands, other languages, and different styles of warfare—he shared his experiences with his new lord and quickly became a trusted confidante. Lockley even supposes that under the cultural obligations of Japan’s social ranking system at the time, there wasn’t a Japanese person who would be comfortable becoming what Yasuke became to Nobunaga—a close friend.73

Then one morning, Nobunaga asked Yasuke to go for a walk. They descended about halfway down the mountain when Nobunaga, quote, “suddenly turned right, down a short path, through an opened gate and into a courtyard. Inside was a modest house, brand new, judging by the sweet resin smell of the fresh timber and the pale look of the unaged wood.”74 They looked around for a moment, and then Nobunaga informed Yasuke that it was all his, with high ceilings made especially for a giant. He presented Yasuke with a short ceremonial sword, officially making him a member of the Oda clan. The ceremonial sword with the Oda crest was the second-highest honor he could give him, falling behind only a fief of his own.

This was a huge deal. Yasuke was almost certainly the first-ever foreign-born samurai, as well as the first Black one. It was an enormous honor, bestowed upon him because Nobunaga had seen his worth. In one fell swoop, he had handed Yasuke both a family, a home of his own, and wealth of his own.

Samurai were the ruling class of Japan; they commissioned building projects, were free to learn philosophy and make art, as well as enforce justice. It was an incredible privilege, especially for someone who had probably been enslaved less than 10 years before. They even had a specific uniform, which Nobunaga had planned for with several sets of clothes specially made in Yasuke’s size. All samurai wore two swords in their belts; Yasuke acquired both quickly; I believe the ceremonial sword Nobunaga had given himwasn’t usually used for actual fighting.

Yasuke began training with the other samurai, sparring with them and learning their sword-fighting techniques even more intimately than he would have been able to by just watching others fight while working for Valignano. He also became, quote, “something of a consultant” for Nobunaga; basic bodyguard duties could be left up to lower-ranking samurai.75 One of Valignano’s colleagues, a Jesuit named Mexia, witnessed how Nobunaga treated Yasuke at Azuchi. He wrote, quote, “Nobunaga never tired of talking to him…as he was also strong and entertaining, he pleased Nobunaga.”76

He also began learning sumo. Nobunaga was a “well-known connoisseur of sumo, and many of today’s codified rules and conventions can be traced back to him.”77 Nobunaga held a sumo tournament sometime in 1581 and partway through he pitted Yasuke against an opponent who was, quote, “more than a foot shorter,” of course, everyone knew this particular match was just for fun since Yasuke had not been appropriately trained yet. For some of them, there would have been, quote, “religious symbolism in the dark-skinned giant, who many equated with a semidivine spirit, engaging in the ring with a human foe.”78

His opponent couldn’t move him at all; next, two opponents ganged up on him, then three. It would take the efforts of four trained sumo wrestlers working together to force Yasuke out of the ring, much to everyone’s delight.79

A few weeks later Nobunaga hosted another horse spectacle, this time of the people of Azuchi who hadn’t been able to see the one in Kyoto. If it sounds like Nobunaga is throwing a lot of parties, he was. He clearly enjoyed them, but it was also probably a way of pacifying his populace, ensuring that obeying him was in their best interest too. As Lockley points out, the Romans called this practice ‘bread and circuses’—Nobunaga might as well have used “rice and spectacles” as an equivalent phrase.80

Beyond entertaining Nobunaga and everyone else, one of Yasuke’s main focuses was to train for the battles that were surely upcoming. Nobunaga was the strongest diamyō in Japan, but he wasn’t the only one, and he had ambitions of conquering other regions. He did this peacefully, through marriage alliances and strategic adoptions, but he also did it with warfare.

Yasuke first tasted Japanese warfare when Nobunaga set his sights on the peasant warriors of Iga, a mountainous land where uninvited passers-through were often kidnapped, robbed, and or murdered. These warriors were often trained as ninja, secretive fighters who could be bought by the highest bidder to perform assassinations or die trying. In fact, three different ninjas had tried to kill Nobunaga over the preceding decade.

But this time, two disgruntled men from Iga had approached Nobunaga, ready to guide Oda troops into the mountains to destroy the Iga warriors—for a price, of course. Nobunaga jumped at the offer, sending 50,000 warriors to Iga, though he and Yasuke stayed behind at Azuchi; it was an overwhelming force—the entire population of Iga at the time numbered around 10,000.81 A nod, perhaps, to how fierce and clever the Iga troops were.

In early November 1581, Nobunaga and Yasuke traveled to Iga with reinforcements. By the time they got there, the battle was seemingly over—the defenses collapsed, and the region was, quote, “engulfed in flame.”82 Bodies remained in the snow, too many dead to bury.

But as they inspected the vestiges of the attack, it turned out that the famous ninjas had one last sneak attack planned. They had planted explosives among the bodies, and as those went off and smoke filled their air, the final remaining Iga warriors rose from the snow, attacking the Oda warriors who had rained down such destruction. It was Yaskue’s first battle as a samurai; he defended Nobunaga, who was actively fighting himself. The Oda warriors won handily, but it had been a deadly and terrifying last stand.

They were back in Azuchi for the new year celebrations. As 1581 became 1582, Yasuke stood in attendance to Nobunaga while his lords approached him to pay their respects. The festivities lasted for two full weeks, with processions and horse shows and bonfires.

On March 28, 1582, Yasuke departed Azuchi castle at Nobunaga’s side, on the way to their next battle, this time against the nearby Takeda clan. He possibly rode with or near other generals of Nobunaga’s military, including Tsuda Nobutsumi, Takayama Ukon, and Akechi Mitsuhide. It had been only a year since Yasuke had been transferred into Nobunaga’s service, and his life had clearly greatly changed.

The battles went well for Nobunaga, and soon the severed heads of the former Takeda lord as well as his son, were brought before Nobunaga for an important ritual observed through samurai history: Victors would share a drink with the head of their dead enemy to, quote, “pay last respects to a worthy foe.”83 Victors would pray for their dead foe, speaking to the head and honoring it.

But Nobunaga did not do that. He taunted both the severed heads of his fallen enemies, gloating over his victory, even reportedly slapping them around. This would have made Nobunaga’s entourage deeply uncomfortable; it was, quote, “a terrible breach of protocol,” and Lockley guesses that they probably found it disgraceful, and wished they weren’t there.84 I get it—I also wish this hadn’t happened nearly 500 years ago and I don’t even know anyone involved. I cannot imagine how uncomfortable it would be to witness this today, even without samurai cultural norms to dictate what should be done in this situation.

The campaign pushed forward, chasing Takeda samurai fugitives, taking down the whole power structure of the Takeda clan so it could be replaced with the Oda clan’s powerful figures. Nobunaga would, eventually, assign his own trusted samurai fiefs from their region; Yasuke must have wondered if he’d be assigned one someday. If Nobunaga promoted Yasuke this way, he would be the first African ever given Japanese land, to be responsible for Japanese lives—a fief implied permanence and responsibility, something no other European or African had ever wanted or needed in Japan. It would be another enormous honor to Yasuke—it would mean wealth and position, yes, but also playing politics, marrying someone highborn, and having heirs with something to gain or lose.

Despite his questionable behavior in victory, Nobunaga was considered a beloved ruler by even his lowest-ranking citizens. He immediately lowered the taxes farmers in the newly conquered lands paid, set down new laws for punishing criminals, and committed money to rebuilding and improving local infrastructure. He might have gotten rid of enemies with swords and fire, but Nobunaga made allies with money, respect, and rule of law.

They returned to Azuchi soon after, Nobunaga’s generals with them. It was only early spring; Nobunaga had conquered two major regions in a matter of months. He decided, naturally, that he needed a holiday, and decided on a trip to Mount Fuji. The mountain is holy in the Shinto religion, and Nobunaga had never been able to go. But it was under the protection of his main ally, Tokugawa Ieyasu, so he decided it was finally time.

Nobunaga’s procession to Fuji was grand in the extreme—grand doesn't cover it, it feels like. It was a “luxurious pilgrimage,” which Ieyasu ensured by building new bridges and clearing new roads to make his passage more comfortable.85 At each site, Ieyasu constructed a whole new teahouse so that, quote, “Nobunaga might contemplate the surroundings with refreshment and in suitable comfort and his host could impress with his tea implements collection.”86 He provided for every member of Nobunaga’s enormous entourage, as quote, “respecting Nobunaga’s troops showed reverence to their commander; hundreds of huts were constructed for Nobunaga’s soldiers each day.”87 Meanwhile, I can’t get the LA city government to fix the pothole that’s been on my street for a year. Where is Ieyasu when you need him?

Unfortunately, the teahouses were too small for Yasuke to fit into. They’d been designed with Japanese proportions in mind, and the average height of Japanese people at this time was just around five feet. Ieyasu probably apologized profusely, but I guess the houses fit together like premade houses today, and couldn’t be altered by the next day’s stop.

They returned to Azuchi in May 1582, having enjoyed a truly lavish vacation. Little did any of them know, their time together was coming to an end.

A few weeks later, on June 20th, Yasuke set out for Kyoto at Nobunaga’s side, just thirty soldiers traveling with him. They were on their way to a castle that was being besieged by Nobunaga’s general Hideyoshi. He had gone so far as to use a few thousand laborers to quickly reroute an entire river, turning the castle into an island.88 This incredible feat of engineering earned Hideyoshi his own place in history books, but it also meant that he needed reinforcement; his men were exhausted.

They arrived in Kyoto the same night, and they stayed at Honnō-ji Temple, the Buddhist campus where Yasuke had first met Nobunaga. They were planning to go on to the castle the next day, but Nobunaga had sent word to his general Akechi Mitsuhide to travel straight to Hideyoshi’s aid with his own force of 13,000 warriors.89

Up to this moment, there was seemingly no hint that Mitsuhide had had enough of Nobunaga, his swagger, his power, and his dishonorable behavior. Just months before, Nobunaga had humiliated Mitsuhide in front of his entire household. Years before that, Nobunaga had betrayed Mitsuhide’s mother, getting her killed in a convoluted exchange of pride and prisoners.90 And now Mitsuhide had prayed to the gods for guidance—and they told him to kill Nobunaga.

On June 18, 1582, Mitsuhide had joined eight gentlemen poets at a shrine Kameyama for a renga session—a form of collaborative poetry where multiple poets added new stanzas to a poem in turn.91 For centuries, renga were employed as a performance prayer, dedicated to a deity to grant victory in battle. Mitsuhide began with the first stanza, which was peppered with homonyms and double-entendres. One translation of it could read, quote,

The time is now,

the fifth month,

when the rain falls.92

Innocuous, right? Well, it could equally be translated as,

It is the fifth month,

Now Toki shall reign,

Over the lands under heaven.93

Toki was Mitsuhide’s ancestral clan name, so this is clearly a bit of a threat.

While Nobunaga entertained Kyoto nobles, including the emperor, with a reduced security team, Mitsuhide’s forces marched through the night of June 20th, arriving in Kyoto just before dawn on June 21, 1582.94 They surrounded the temple and stormed just as the sun rose. The men inside slept, and since Kyoto had been a peaceful city for more than ten years, since Nobunaga had taken over, there was only a small number of guards or police awake; they were easily killed without alerting their targets.

At this time of Japanese warfare, it was customary to use a conch shell to signal the start of a battle. It was probably this very sound that woke Nobunaga and his thirty pages up; the enemy was already inside the compound, surrounding the quarters where they slept. It was 30 samurai against 13,000—you know where this is going.

The 30 put up a decent fight; Yasuke, Nobunaga, and his favorite, Mori Ranmaru, fought valiantly, killing perhaps dozens of their attackers. But when it became clear that this battle could not be won, they retreated into a backroom of the temple, where Nobunaga performed seppuku, the ritualized suicide that some samurai performed rather than be caught.95 As Nobunaga stabbed into his own torso, Ranmaru probably cut off his head to lessen the agony of it. Lockley proposes that after Ranmaru cut off Nobunaga’s head, he requested that Yasuke do the same for him.

Before dying, Nobunaga probably instructed Yasuke to take his head and sword to his son Nobutada, who lived just a block away.96 If either or both were captured by Mitsuhide—and by then they had probably figured out that it was Mitsuhide who had betrayed them—they would become powerful symbols for him to capture Nobunaga’s territory and thousands of samurai vassals. So Yasuke wrapped up both heads with whatever cloth he had, took both swords, and ran to Nijō Palace next door.

He almost certainly encountered Mitsuhide’s soldiers along the way, killing an unknown number as he made his desperate escape. He made it to Nobutada, presenting him his father’s head; both knew that Mitsuhide would come for them next.

Nobutada certainly had his own samurai in residence, but not enough to rival Mitsuhide’s invading force. Lockley estimates that it took less than an hour for Mitsuhide’s forces to capture the palace; Nobutada probably also performed seppuku rather than be captured. His head and sword were probably hidden along with his fathers to prevent them being used as symbols for Mitsuhide’s revenge.

The battle was over within just a few hours of sunrise.97

Yasuke, amazingly, was left alive. He didn’t defeat all 13,000 men—they just forced him to the Kyoto Jesuit temple, giving him back to the Portuguese men who had brought him to Japan. He remained at the temple at least until the fall, healing from the numerous wounds he’d surely sustained that night.

Mitsuhide, it should be said, reigned over Nobunaga’s lands for a mere thirteen days. His betrayal was too great, Nobunaga too well-loved; he was chased down and killed in a swamp by a farmer or thief, his family name ruined. Hideyoshi, the general who had rerouted a river to create a castle island, took over, continuing Nobunaga’s unification of Japan.

Lockley is pretty sure that Yasuke participated in at least one more battle in Japan, for the young lord Arima he had met when he first arrived. The cannons that Valignano had ordered as wedding presents all those years ago had finally arrived; Yasuke, familiar with the armament, probably taught Arima’s forces how to use them.98 In May 1584, he probably helped Arima’s men defeat the Ryūzōji after years of stalemates and sieges. His expertise with the cannons helped them defeat the invading military that was estimated to be three times the size of the Arima-Satsuma alliance that had been established while Yasuke was away.99 We’re not totally sure about this though, it’s only an educated guess made by Lockley from vague records.

History lost track of Yasuke after the autumn of 1582, when he was still in his early 30s. Lockley supposes Yasuke remained in Japan; he would have retained his status as samurai despite Nobunaga’s death, though it’s not clear where he lived or whose service he entered after. It would have been preferable to life in Europe, where Black people were regularly enslaved and discriminated against; he had the best chance at a happy life in Japan at this time. Moreover, samurai usually traveled with their wealth, coins looped around their waist, so it’s not hard to believe that Yasuke bought his own way after this; even though he’d lost his home with Nobunaga’s death, he still had money. After 1582, there are stories and depictions of wealthy African men with African/Japanese children; whether one of these is Yasuke is impossible to say. But maybe.

He may have also returned to Africa where he was born, or India, where he’d spent many years, or accompanied Jesuits to Europe, which he’d never seen. We don’t know. But it’s nice to hope for the best for Yasuke. It’s a nicer ending than dying from injuries sustained while fighting in this final battle, at least.

That is the story of Yasuke! I hope you enjoyed this episode! You can let me know your thoughts by following me on Substack, Twitter, and Instagram as unrulyfigures. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks discover the show.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Clark. My research assistant is Niko Angell-Gargiulo. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com If you’d like to send us something, you can send it to P.O. Box 27162 Los Angeles CA 90027.

Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

“Dinka | History, Culture & Language | Britannica,” August 2, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Dinka.

Germain, Jacquelyne. “Who Was Yasuke, Japan’s First Black Samurai?” Smithsonian Magazine, January 10, 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-was-yasuke-japans-first-black-samurai-180981416/.

Lockley, Thomas, and Geoffrey Girard. African Samurai: The True Story of Yasuke, a Legendary Black Warrior in Feudal Japan (Reissue). New York, NY: Hanover Square Press, 2021.

Moon, Kat. “The True Story of Yasuke, the Legendary Black Samurai Behind Netflix’s New Anime Series.” Time, April 30, 2021, sec. Entertainment. https://time.com/6039381/yasuke-black-samurai-true-story/.

Russell, John G. “Excluded Presence : Shoguns, Minstrels, Bodyguards, and Japan’s Encounters with the Black Other.” Jinbun kagaku Kenkyusho, Kyoto University, March 2008. https://doi.org/10.14989/71097.

Tsujiuchi, Makoto. “Historical Context of Black Studies in Japan.” Hitotsubashi Journal of Social Studies 30, no. 2 (1998): 95–100.

Wright, David. “The Use of Race and Racial Perceptions Among Asians and Blacks: The Case of the Japanese and African Americans.” Hitotsubashi Journal of Social Studies 30, no. 2 (December 1998): 135–52.

Yasuke – Story of The Real Black Samurai. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://yasuke-san.com/.

Yasuke: An African Warrior in Japan with Prof. Thomas Lockley. Lunchtime Lecture. Aga Khan Museum. Accessed September 13, 2023.

.

Yasuke – Story of The Real Black Samurai, accessed September 13, 2023, https://yasuke-san.com/.

Thomas Lockley and Geoffrey Girard, African Samurai: The True Story of Yasuke, a Legendary Black Warrior in Feudal Japan (Reissue) (New York, NY: Hanover Square Press, 2021).

Lockley and Girard, 78

Lockley and Girard, 182

Lockley and Girard, 179

Lockley and Girard, 183

Lockley and Girard, 81

Lockley and Girard, 184

Lockley and Girard, 187

Lockley and Girard, 77

Lockley and Girard, 77

Lockley and Girard, 62

Lockley and Girard, 60

Lockley and Girard, 60

Lockley and Girard, 61

Lockley and Girard, 78

Lockley and Girard, 22

Lockley and Girard, 82

Lockley and Girard, 16

Lockley and Girard, 21

Lockley and Girard, 22

Lockley and Girard, 26

Lockley and Girard, 29

Lockley and Girard, 31

Lockley and Girard, 32

Lockley and Girard, 119

Lockley and Girard, 123

Lockley and Girard, 125

David Wright, “The Use of Race and Racial Perceptions Among Asians and Blacks: The Case of the Japanese and African Americans,” Hitotsubashi Journal of Social Studies 30, no. 2 (December 1998): 135–52.

Lockley and Girard, 83

Lockley and Girard, 40

Lockley and Girard, 70

Lockley and Girard, 43

Lockley and Girard, 47

Lockley and Girard, 62

Lockley and Girard, 66

Lockley and Girard, 64

Lockley and Girard, 65

Lockley and Girard, 68

Lockley and Girard, 49

Lockley and Girard, 50

Lockley and Girard, 84

Lockley and Girard, 84

Lockley and Girard, 86

Lockley and Girard, 89

Lockley and Girard, 96

Lockley and Girard, 97

Lockley and Girard, 98

Lockley and Girard, 99

Lockley and Girard, 103

Lockley and Girard, 105

Lockley and Girard, 108

Lockley and Girard, 109

Lockley and Girard, 110

Lockley and Girard, 111

Lockley and Girard, 112

Lockley and Girard, 114

Lockley and Girard, 118

Lockley and Girard, 118

Lockley and Girard, 126

Lockley and Girard, 126

Lockley and Girard, 135

Lockley and Girard, 135

Lockley and Girard, 136

Lockley and Girard, 144

Lockley and Girard, 155

Lockley and Girard, 161

Lockley and Girard, 162

Lockley and Girard, 169

Lockley and Girard, 171

Lockley and Girard, 193

Lockley and Girard, 196

Lockley and Girard, 197

Lockley and Girard, 198

Lockley and Girard, 212

Lockley and Girard, 212

Lockley and Girard, 219

Lockley and Girard, 221

Lockley and Girard, 221

Lockley and Girard, 221

Lockley and Girard, 234

Lockley and Girard, 239

Lockley and Girard, 261

Lockley and Girard, 262

Lockley and Girard, 273

Lockley and Girard, 274

Lockley and Girard, 274

Lockley and Girard, 279

Lockley and Girard, 287

Lockley and Girard, 284

Lockley and Girard, 282

Lockley and Girard, 283

Lockley and Girard, 283

Lockley and Girard, 293

Jacquelyne Germain, “Who Was Yasuke, Japan’s First Black Samurai?,” Smithsonian Magazine, January 10, 2023, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-was-yasuke-japans-first-black-samurai-180981416/.

Lockley and Girard, 304

Lockley and Girard, 312

Lockley and Girard, 330

Lockley and Girard, 332