Hey everyone,

So excited to bring you this episode on Sarah Bernhardt! I feel like two months ago I didn’t even know who she was and now I am kind of obsessed with her. That probably comes across in the episode, haha. Not only was she this charismatic and incredible actress, but she also lived her life on her own terms, which is my favorite thing about any unruly figure I cover here. She also really set the path for what modern celebrity looks like, in good and bad ways, as we’ll see. Her life was full of glamorous tours and even more glamorous love affairs, including several heads of state. I can’t wait for y’all to get to know her.

Questions, comments, concerns? Drop ‘em in the chat!

Some news: You can now follow me on TikTok and Threads in addition to Twitter and Instagram. The world of social media is so weird right now, so maybe just join the Substack chat instead.

All right, let’s get into Sarah Bernhardt’s life!

🎙️ Transcript

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m going to be covering Sarah Bernhardt, an incredibly accomplished actress, sculptor, and one of the most famous women of her age.

But before we jump into Bernhardt’s life and how she became an incredibly famous independent actress, I want to give a huge thank you to all the paying subscribers on Substack who make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! Each of these episodes takes me nearly 30 hours of work, which means they’ve become a full-time job. So if you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber for just $6/month or $60/year! Contributions help ensure that I will be able to continue doing this work. Becoming a paying subscriber will also give you access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates on the upcoming Unruly Figures book. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

Okay, let’s hop in.

Sarah Bernhardt was born in Paris on October 22, 1844. Or maybe it was in July or September, and it might have been 1843 or even 1841. We’ll never know, because Sarah Bernhardt was, and I quote biographer Robert Gottlieb here, “a relentless fabulist when recounting [her life].”1 Any records we could double check, like birth certificates, were lost when the Hôtel de Ville, Paris’s city hall, was torched during the Commune uprising in 1871.

This idea, that Sarah heavily embellished her life, is pervasive throughout stories about her. Bernhardt’s own memoirs are so clearly fabricated that I didn’t even bother to read them, though I’ve heard My Double Life is a fantastic–if unreliable–read. Many of the biographies about her are contradictory, and probably all of them acknowledge that most of her childhood is shrouded in mystery and revered through legend. Alexandre Dumas fils, the son of the famous Alexandre Dumas who wrote The Three Musketeers, even once said of Bernhardt’s famous thinness, quote, “You know, she’s such a liar, she may even be fat!”2

So that’s what we’re working with here. You might be wondering why I’m even covering an actress–it’s true that Bernhardt didn’t lead a revolution and she wasn’t a political activist, but she did live outside of polite French society’s boundaries and she was hugely celebrated almost because she did. The world didn’t love Sarah Bernhardt in spite of her weird habits, her constant scandalous love affairs, and her unrelenting dedication to fulfilling her every whim, they loved her because of all that.

And they loved her story. They loved the rags to riches arc of her life, this idea that she both came from the bottom rung of society–her mother was a young courtesan or sex worker–but also had this kiss of royalty on her. Her father was rumored to be a young naval officer named Morel, from Le Havre, but from a young age she was watched over by the duc de Morny, the most powerful man in France due to being the half-brother of emperor Louis-Napoléon. Unfortunately, Sarah’s mother, Julie or Judith Bernhard, is almost the main villain of Sarah’s life. It’s well documented that she didn’t love her oldest daughter very much and could be very cruel to her. When she was quite young, Julie sent Sarah away to live with a nurse in the Breton countryside, which was pretty common back then, but for Bernhardt felt like a great wound.

The name she was given at birth, Henriette-Rosine, didn’t stick around for long. She insisted on being called Milkblossom starting around age four; not sure where she got that one from.3 Sarah, or Milkblossom I guess, allegedly once tried to break out of her high chair while her nurse was out in the garden. Of course, Bernhardt accidentally fell into the fire. The nurse’s husband was too sick and limited to his bed at the time, so he cried for help and the neighbors came running. They fished her out of the fire and threw her into a pail of milk to save her skin, and afterward, the whole village came together to find enough butter to make poultices to treat her skin.4 Miraculously she didn’t have a single scar from this ordeal!

Is a word of this true? Almost certainly not. But Bernhardt used this accident to explain why her mother suddenly brought her back to Paris, installing the nurse, the nurse’s husband, and Bernhardt in an apartment near the Seine. Everyone else sort of assumes that in fact Julie just felt that traveling to Brittany regularly was too arduous. Professor Sharon Marcus, in the episode of You’re Dead to Me about Sarah Bernhardt, points out that this little fable tells us a lot about how Bernhardt wanted to be seen—as a “willful, impulsive daredevil, narrowly escaping death only to rise—literally—from the ashes.”5

The next legend has the nurse’s husband dying, so the nurse remarries and moves to be with her new husband. Of course, Bernhardt is whisked away to a new apartment and no one knows where she is. But her beloved Aunt Rosine, who she was named after, finds her by some miracle. Rosine promises to visit again the next day, but of course, Bernhardt doesn’t believe this so she flings herself in front of Aunt Rosine’s carriage from a window and broke her arm in two places in the process. Bernhardt apparently spends two years recovering from this in a, quote, “chronic state of torpor" and remembers nothing.6 This story is “obediently repeated” by a lot of biographers but it also has little to no basis in reality.7

Biographer Robert Gottlieb, whose biography Sarah: The Life of Sarah Bernhardt I relied on for this episode, supposes that these dramatic scenes of near-death her more interesting and less painful that the, quote, “obvious truth” that Julie was “a slapdash and irresponsible mother.”8 Though these stories aren’t literally true, they do seem to convey a central truth for Bernhardt: quote, “She felt her mother was lost to her and that, physically or metaphorically, she had to jump from a window and break her bones in order to gain her attention.”9

At seven, Bernhardt was finally enrolled in school. Her mother sent her to a fashionable all-girls boarding school where she apparently was exposed to acting for the first time—an actress from the Comédie Française would show up weekly to recite poetry for the students. Two years later, her otherwise absent father, who was apparently paying for her education, had her transferred to a fashionable convent school in Versailles. Bernhardt converted to Catholicism there—her mother was Jewish, though no one in the daily seemed particularly devout—as well as learned how to behave like a lady. This is the first hint we get of some kind of financial support from someone wealthy and well-to-do. Julie was a high-class courtesan, though not one of the grandes horizontales, as they called the truly great courtesans of the royal court at the time. But she probably couldn’t have afforded this very impressive education on her own, hence the idea that the Duc de Morny had taken an interest in Bernhardt from a very young age.

Bernhardt spent six years at the convent school. She loved it there, and Mother Superior Sophie seemed to quickly grasp that Bernhardt could not be coerced but responded well to requests and sympathy. The two got along really well and Bernhardt always remembered her fondly.

And Bernhardt was unruly in the most literal sense. She was, quote, “a scamp and a ringleader, and certainly not an exemplary student: Her only good subjects were geography and art… She was always in trouble, and three times son the verge of being expelled for some outrageous prank. But the other girls looked up to her.”10

While at the convent school, Bernhardt had her first big stage success. She played the Angel Raphael in a play based on the apocryphal Book of Tobit that was supposedly once part of the Old Testament; the tale goes that Raphael told a boy named Tobias how to cure his father’s blindness. Sarah was apparently great as Raphael and was lucky that the archbishop of Paris was in the audience for the performance. He was supposed to perform her baptism, in fact, but then was murdered before he got the chance.

Bernhardt was eventually baptised though, on May 21, 1856, when she was 12 or maybe 15. On the baptismal certificate, her father is listed as Édouard Bernhardt, but we’re pretty sure that’s actually her uncle’s name. Bernhardt also had two little sisters by this point, Jeanne and Régine, who were baptized with her. When Bernhardt’s education was complete a few years later, the convent had transformed her: She’d not only converted to Catholicism but had also learned the manner and speech of upper-class Paris. She also had decided that she wanted to become a nun, but that was not to be.

It’s worth noting here that it was by the time that Bernhardt began going by Sarah. I’m not sure how long Milkblossom lasted, but I think we can assume she was called Henriette-Rosine throughout her time at school. We don’t really know why she changed her name to Sarah, it doesn’t seem like anyone in her family used the name. But Professor Sharon Marcus, in that episode of You’re Dead to Me, supposes that it’s because Sarah is a more traditionally Jewish name than Henriette or Rosine and Bernhardt didn’t want to look like she was hiding her Jewish heritage, despite having been baptized.11 Which is really interesting to me. She always performed under the name Sarah Bernhardt, so this is really the latest point when she could have changed her name.

Bernhardt would have us believe that after she was brought back to Paris, her mother convened a roundtable of all her suitors and clients to have them decide what should be done about her future. There was some idea of Sarah entering the demimonde life as a courtesan, though she had neither the looks nor the temperament for it. Her mother wanted her married, but her education and religious conversion couldn’t change the fact that she was the illegitimate child of a Jewish sex worker; a marriage into proper society was deemed impossible at the moment. Bernhard herself apparently begged to be allowed to return to a convent to become a nun, but it was apparently the Duc de Morny who decided that a girl this dramatic would do well on the stage. He pulled some strings and got her into the acting Conservatory of Paris, where she would learn to act. She studied there from 1860-1862.

In the meantime, Bernhardt befriended her mother’s upstairs neighbor, Madame Guérard. They remained lifelong friends, and Madame Guérard even accompanied Bernhard on all of her world tours. It’s a mark of her discretion that despite this long-term connection, we don’t even know her first name.12

At the same time that Bernhardt was at the Conservatory, she began taking art classes. She had considerable success there—at just sixteen she won a prize for her painting called Winter in the Champs-Élysées.13 She always maintained a love of creating art and became a pretty good sculptor.

For someone who would later become the most famous actress of her age, Bernhardt’s introduction to acting was not a resounding success. Like everything in her life, there are mixed accounts of why. She was a dedicated, some even said “obsessive,” student.14 She always threw herself into anything she did with an intense passion. But she really disagreed with some of the things her acting teachers were telling her—Gottlieb makes the specific point that Bernhardt was explicitly told to never speak to her back with the audience, but she became famous for, quote, “the drama she could wring out of speeches delivered while turned upstage.”15 Not only did she not like a lot of the teachers, but we have hints that she was not well-liked by the Provost or by her peers. She was “too self-promoting,” and that streak of impulsivity remained.16 Still, she committed to really working hard and learning everything that was taught to her, even if she disliked it.

However, she graduated from the Conservatory without top marks. This is the first time we hear criticisms of her appearance—Bernhardt was often described by her contemporaries as excessively thin, far too thin to make it as a beautiful actress on the stage. Her family started to tell her to give up acting because she wasn’t talented enough or thing enough. Ironically, Bernhardt wouldn’t be considered slender by our standards today, and that same family might have been telling her she was too fat to make it as an actress—how beauty standards change! Luckily, the Duc de Morny stepped in again and got her into the Comédie Française acting company.

She debuted in her acting career on August 11, 1862. She played the title role of Racine’s Iphigénie. Critical reaction was not great, and Gottlieb blames this mostly on Bernhardt’s stage fright and inexperience. Supposedly Bernhardt even felt like she’d done poorly and apologized to her teacher, who told her, quote, “I can forgive you, and you’ll eventually forgive yourself, but Racine in his grave never will.”17 But Professor Marcus points out that many of the critics of the day wouldn’t give young actresses good reviews if the actresses wouldn’t sleep with them first.18 Bernhardt had refused to have sex with the much older leading critic, Francisque Sarcey, so everyone followed his lead and gave her bad reviews. Sarcey himself wrote that Bernhardt was “a tall, pretty girl with a slender figure and a very pleasing expression, and the upper part of her face is remarkably beautiful. She holds herself well, and her enunciation is perfectly clear. That’s all that can be said for her at the moment.”19 After her third performance, in Molière’s Les Femme Savantes, Sarcey wrote, quote, “This performance was a very poor business.”20 Clearly she hadn’t given in to his requests for sex in exchange for a good review. Supposedly, Bernhard took poison that night and nearly died, but Gottlieb dismisses this report as overdramatic.

At the same time, Bernhardt’s relationship with her mother was getting steadily worse. Her mother had only ever cared about her middle child, Jeanne, and rejected both Sarah and Régine outright.

Also, despite Bernhardt’s paying job at the Comédie Française, her mother was trying to sell her to the highest bidder. Her friend-turned-mortal-enemy Marie Colombier wrote that she witnessed Julie forcing her 16 or 17-year-old daughter to sit in the lap of an older rich man that had come to dinner.21 Bernhardt apparently shuddered as he groped her, but it didn’t go further. He paid for the pleasure of it, and Julie took the money away to pay her rent.

If this was the only account of it, we might ignore it since it was written after Colombier and Bernhardt had their massive falling out. However, Gottlieb notes that it was an open secret in Paris that Julie had, quote, “made whores of her daughters as soon as they turned thirteen.”22 Bernhardt was safely ensconced at the convent at that age, so her mother probably tried to get her involved after she moved back to Paris, but it sounds like Jeanne and Régine were not so lucky.23 It’s a very sad thread through the lives of the three girls. Jeanne and Régine would both end up remaining courtesans throughout their short lives.

Around this time Bernhardt met her first real lover, a wealthy 30-year-old man named Émile, Comte de Keratry. There are mixed accounts of this as well. Some say that they met and really fell for one another; others claim that this was set up by Julie so that Émile might give Bernhardt (and therefore her mother) money, much like the Duc de Morny was doing for Julie and her sister (yes, he had taken both as mistresses). Bernhardt barely mentions Keratry in her memoirs except to talk about how they crossed paths again 10 years later. We’ll get to that.

At the Comédie Française, the entire company would pay their respects to Molière in a little ceremony on his birthday. They would salute or curtsy to his bust in the theatre. So Bernhardt participates in this for the first time in January 1863, and she brought her little sister Régine along. Well, Régine accidentally stepped on the train of an important elderly actress, Madame Nathalie, who shoved the very small child into a marble pillar.24 Régine began bleeding and crying, of course, so Bernhardt called Nathalie, quote, “You miserable bitch,” and slapped her, hard.

Unfortunately, Nathalie had the highest rank an actor could achieve, and so she demanded an apology from Bernhardt. The young actress of course said no, since Nathalie had severely injured her younger sister. Management got involved, trying to get someone to apologize for what happened, and it seems like this incident dragged on for weeks. Finally, in March 1863, Bernhardt stormed out of the Comédie Française, tearing up her contract as she went.25

But if we were worried this would stop her in any way, it of course did not. By standing up to Nathalie, she had become a sensation in the Paris theatre world—a scandalous topic of conversation, as Gottlieb put it.26 She was unemployed, but now the more popular actress.

She nearly immediately joined the company at the Gymnase, a fashionable theatre that actually still exists. Bernhardt appeared in about half a dozen productions while she was there, mostly in small roles. Supposedly bored of this after a year, Bernhardt ran off to Spain in late April 1864 to see the sights and enjoy herself. She was only convinced to return to Paris because she heard her mother was very ill.

However, it’s more likely that Bernhardt ran off to Spain in a panic because she’d realized she was pregnant. Her son Maurice was born in December of that year, so she’d have just noticed in late April. Who the father was is the big question—Bernhardt often joked that it was some famous person or another, suggesting anyone from Victor Hugo to the Duke of Clarence, though the Duke of Clarence was also born in 1864 so he’s clearly not a contender.

The most commonly talked about candidate is the handsome Belgian Prince Henri de Ligne. He and Sarah did meet, though how is a matter of some debate. In the most romantic version, it seems that they were truly in love. He even proposed marrying her, though, of course, his family intervened to make her see that a crown prince couldn’t possibly marry an illegitimate actress, so she breaks it off with him though it breaks her heart to do so. Gottlieb points out that this seems like quite a tall tale, told by Sarah both to put Maurice’s illegitimate birth in the best possible light and to, quote, “satisfy Sarah’s need to think of herself as having enjoyed a beautiful, ill-fated love affair… a prince ready to marry her! An impeccable aristocratic background for her adored Maurice! Heroic self-sacrifice!”27

Of course, some think that if Prince Henri was the father of Maurice, the romantic version of the tale is just that—a tale. Another version goes that he was a client of hers and that she was doing sex work in addition to acting to get by. She apparently wrote to him asking for help, but he told her, quote, “When you sit down on a bundle of thorns, you can’t tell which one of them is pricking you”—a euphemistic way of saying there’s no way to prove he’s the father.28 He may have given her some money to go away, but he certainly didn’t claim Maurice as his.

Of course, Bernhardt was never publicly concerned about Maurice’s illegitimacy. She wasn’t embarrassed about being a single mother and gave Muarice her own last name instead of his father’s. She would often take Maurice with her to fashionable parties where she would make sure that she was announced as “Miss Bernhardt and son.”29 Instead of hiding the scandal, she leaned into it—quand même, as she said.

Bernhardt wasn’t really working at this time. Her rush off to Spain had ended her contract at the Gymnase. For a long time, biographers just brushed over this, but today we know for sure that Bernhardt was working as a courtesan in Paris. In 2006, renowned historian Gabrielle Houbre transcribed a rarely-seen ledger kept by the police of Paris from 1860-1870: The Book of the Courtesans. Summer Brennan described the original ledger as, quote, “large and heavy, with a worn leather binding, brass hardware, and a broken lock. It contains the criminal files of a group of women called Les Insoumis— ‘the Undominated.’ These were women who lived their lives outside the bounds of polite society, but who refused to register as prostitutes.”30 The Paris vice squad kept an eye on them, surveilling them for various illegal activities to see if. they could be in control.

Right now in Paris, as I record, that book is on display at the Petit Palais. The page it’s turned to shows the entry for Sarah Bernhardt.

Bernhardt, it seems, didn’t really talk about this part of her life. Or at least, she never framed it as sex work; perhaps she didn’t really see it that way. Mistresses were given gifts, and she was just a mistress to several powerful people. She certainly never called herself a prostitute.

And Gottlieb points out that even has a courtesan, Bernhardt did things her way. Instead of sex for money, she set up, quote, “a unique situation that she fashioned through her sexuality, her charm, and her common sense. In the white-satin salon of her new apartment in the rue Duphot she managed to establish a king of court, made up of a group of distinguished men who were seemingly content to pay joint homage to her while sharing her favors openly and with equanimity.”31 Among this group of men was Khalil Bey, an Egyptian diplomat and art collector, the industrialist Robert de Brimont, the banker Jacques Stern, the journalist Arthur Meyer, and Henri Roger de Cahuzac, the Marquis de Caux.

One of the joint ventures of all her gentleman suitors was to buy Bernhardt an elaborate coffin that she had always wanted.32 She loved this thing and took it with her everywhere she went, even on all of her international tours. Later she would be photographed sleeping in it, perhaps as a joke, but that photo would spawn the rumor that she always slept in it. Professor Marcus supposes that it might have been a publicity stunt, but also noted that Bernhardt had quite maximalist gothic tastes when it came to interior design and fashion.33 We know, for instance, that she hung black curtains embroidered with bats and kept a skeleton just, like, around the house, and she also famously wore a hat topped with a stuffed bat.34 Later, Victor Hugo would give her a skull inscribed with a quote as a gift.

After two years of almost genteel unemployment, in 1866 Bernhardt managed to join the Odéon, the second-most famous and respected theatre in France. The theatre had two directors at the time, Charles de Chilly and Félix Duquesnel; Chilly didn’t like Bernhardt basically on sight, but Duquesnel did. Nearly thirty years later, he would remember their meeting in a vivid description. It went, quote,

There stood the most adorable creature imaginable—Sarah Bernhardt in all the glory of her youth. She wasn’t just pretty, she was more dangerous than that… Our interview was very quick—we understood each other immediately. I felt that I was face to face with a marveously gifted creature of rare intelligence and limitless energy and willpower hidden behind her delicate appearance. She was everything that was entrancing and seductive as a woman; artistry emanated from her entire being. All she needed was to be started off in the right direction and be exposed to the public.35

Duquesnel would continue to love Bernhardt for years. I love this little gem of a conversation they apparently once had. She was begging him to read a play she wanted to perform, even offering to read it for him, and he quickly said, quote, “No, no, your voice is treacherous. It can ,ake lovely poetry out of the stupidest lines.”36

It was really at the Odéon that Bernhardt came into her own. She acted in a variety of classical ingénue roles, but it was playing a ten-year-old boy in Racine’s Athalie that she had her first big success, winning over crowds and critics alike.37 Several months later, she showed how thoroughly she had conquered the public and become a favorite of young Parisians when a protest broke out at Odéon. The theatre had announced they’d put on Victor Hugo’s famous Ruy Blas, a, quote, “barely masked cry for political reform,” but of course the French government had forced them to cancel it.38 Instead the theatre put on Kean, by Alexandre Dumas pere, but students from the nearby Sorbonne loudly protested the change. When the show began, the students began shouting over the performers. It wasn’t under Bernhardt stopped her own lines to shout at the students that, quote, “if the students were so dedicated to justice, it was hardly just of them to blame Dumas for the banning of Ruy Blas.”39 Amazingly, this worked. They actually sat down and watched the performance. Soon after, students took to calling themselves Saradoteurs.

Her popularity continued to grow until 1869, when she found the part that would bring her to true stardom. The play was Le Passant, The Passerby, written by François Coppée. Bernhardt played Zanetto, the man who one night “passes by” an aging courtesan, Silvia. Bernhardt had already played a few male roles, as I mentioned, but playing this trouser role of Zanetto is what really launched Bernhardt into fame. She played the role hundreds of times. She even played the role at the palace before Emperor Napoléon III and Empress Eugénie.

Around this time, Bernhardt first slept with her leading male costar, which would become a habit. Her love life, as we’ve already started to see, was a source of a ton of gossip and rumor. Not only did she apparently have affairs with several men in the company at the Odéon, including a father and his son concurrently, but she went on to have an affair with Victor Hugo, who was 42 years her senior. It’s also rumored that she had an affair with Napoléon III after he saw her perform in Le Passant and that she later went on to have a relationship with Edward, Prince of Wales.

One of Bernhardt’s lovers was Charles Haas, who was handsome, fashionable, and famous in the 1860s for his success with women. Today he’s remembered almost solely for being Bernhardt’s lover and for inspiring novelist Marcel Proust’s character Charles Swann. (Bernhardt herself inspired La Berma.) Her affair with Haas ended quickly, but they remained friends until he died in 1902—in fact, Gottlieb notes that staying friends with her exes was one of Bernhardt’s best talents.

Then, in July 1870, the emperor declared war on Germany. The Franco-Prussian War was a disaster for the French, but it turned Bernhardt into a war hero. She had been in the south of France when the war began, and she rushed back to Paris when she heard the news. She got her family out of the city, then she got permission from Duquesnel to use the Odéon, which had closed because of the war, as a military hospital for soldiers. She called in every favor and friend to get the provisions she needed. Bernhardt had always had patriotic tendencies, but this was her chance to prove it.

And this is where the Comte de Keratry comes back! He was the prefect of the Seine at the time, so he was able to send her all the food supplies she needed. He even passed over his fur-lined coat to her. Other friends helped her move everything out fo the theatre to make room for beds and cots—and just as the siege of Paris began, her military hospital was ready.

The injured and dying flooded in. She had hundreds of men under her care, and though it’s unclear where she actually learned to nurse people, she did nurse many of them back to health. As the siege worsened and the shelling grew more intense, Bernhardt actually traveled to a battlefield at Chatillon, where she encountered hundreds of men dying and no way to transport them all to a hospital. She was very traumatized by this.

The armistice was signed in January 1871, after just six months of fighting. It was a humiliation for France. But for Bernhardt, the worst of the humiliation came when she found out that her family had moved from The Hague, where she had sent them, to Frankfurt, in Germany. They had just lost a war against the Germans, a war Bernhardt had patriotically supported, and her family had moved to Germany without leaving so much as a forwarding address! She instantly went to Germany and forced them home, shepherding eleven people across a still smoldering war zone with little but her wits and a revolver—at least, according to her memoir.40

Then, just weeks, later the Paris Commune uprising began. The working class sealed the capital off from the rest of the country, resulting in siege warfare, street fighting, hostages, executions, and terror until the government prevailed. It was while Paris burned that all the records of Bernhardt’s early life were lost. She fled the city to St. Germain-en-Laye.

Once that was squashed, Bernhardt was called back to Paris to resume rehearsals at the Odéon; it had been about a year since her last performance. She knew something was about to change for her. She wrote, quote, “I was awaiting the event which was to consecrate me a star. I did not quite know what I was expecting, but I knew that my Messiah had to come. And it was the greatest poet of the century who was to place on my head the crown of the Elect.”41

Of course, she was referring to Victor Hugo, recently returned from his nineteen-year exile in the Channel Islands. Since the French government had been replaced with a republic, it was finally safe for the Odéon to put on Ruy Blas, the show that had been canceled a few years before. Bernhardt landed the role of the Spanish queen, Doña Marie de Neubourg. Hugo himself was directing, and they were instantly charmed by one another—after opening night, he apparently got down on his knees and thanked her for bringing his Queen to life so perfectly. This is when her affair with Hugo began—he was seventy and she was twenty-seven. It seems that their affair lasted for quite a while; Hugo’s private journals are full of mentions of Bernhardt.

Bernhardt had already let go of a lot of what she had learned at the Conservatoire about acting. Her acting style was unique, and she had this very special voice that people found it, quote, “truly magical” but also elusive—apparently no one was quite sure how to describe it.42 According to Professor Marcus, there are dozens of contemporary nineteenth-century debates out there about whether her voice was more silvery or more gold, which I think is a fascinating analogy to make. Marcus described her voice as somewhat alien, in fact, because she has this vibrato to it that we don’t hear much today.43 I’ve included links to hear her read some poetry in the show notes. Even though these recordings are over a hundred years old and are crackling and fizzy, her voice still projects such power! On top of this, she was apparently somewhat hyperflexible, and she would often bend her body into intense serpentine shapes and perform very intense death scenes.44 Her performances were said to give people almost electric shocks—electricity was new and they felt that she was electrifying.

Soon after the Odéon reopened and Bernhardt electrified Paris as Hugo’s queen, the Comédie Française was all but forced to admit that letting Bernhardt go all those years before had been a mistake. Émile Perrin, head of the theatre, invited Bernhardt to a meeting. He offered her a significant raise and the respect of being a member of the company, and Bernhardt had to take it. She later wrote, quote, “I left the Odéon with very great respect, for I adored and still adore that theater.”45 But it was on to bigger and better. Or, so it seemed.

The problem was that the Française was organized radically differently from Odéon. It was more traditional, more conservative, and the senior actors in the company were not eager to see the, quote, “defiant rule breaker, the glutton for publicity, and the representative of a new, more realistic, more exciting approach to acting” return to their stage.46 And Bernhardt, though popular with the crowds, would not fit in with the company much at all, it turns out.

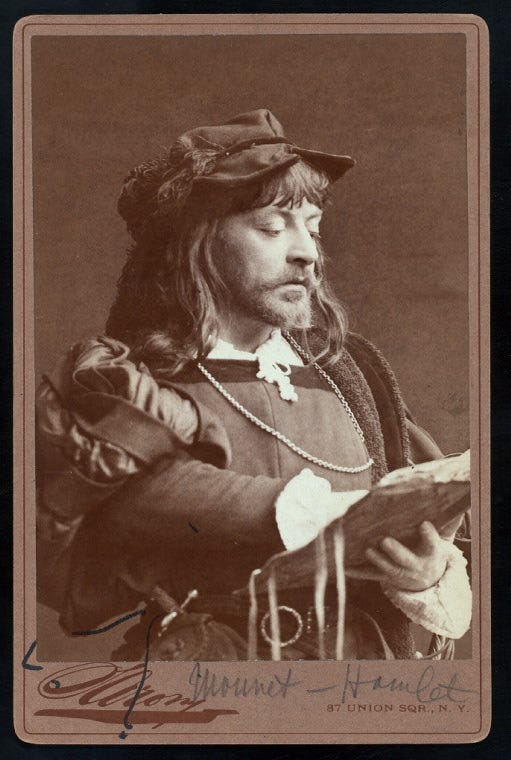

Soon after she joined the Française, her old leading man from the Odéon, Jean Mounet-Sulley joined as well. Since they both had striking good looks and immense talent they were immediately paired together in several plays—and quickly became a couple off-stage as well. As biographer Gottlieb writes, quote, “He was ardent, powerful, jealous, possessive, demanding—and he was moralistic, highly conventional Protestant who believed in faithfulness, marriage, and monogamy. She was Sarah.”47 For over two years they remained involved—he trying to tame her, her resisting his efforts. They were passionate and intense people, and so their relationship was fittingly tempestuous and intense as well.

On stage, they were an enormous success. Jean Cocteau, the French poet and filmmaker, once wrote, quote, “What could they possibly have to do with convention, tact, poise, these princes of the unconventional, these tigers grooming themselves and yawning before the entire world, these forces of artifice at odds with that force of nature, the audience?”48

In late 1873, her younger sister Régine was living with her once again. Well, that is, Régine was dying in Bernhardt’s home, slowly and painfully succumbing to tuberculosis. Bernhardt didn’t leave her side for a second, installing Régine in her bed and sleeping in her coffin next to the bed so she could attend to Régine at night. When Régine eventually died, she was just 19 years old. Bernhardt was so devastated that her doctor recommended she take time off to rest; even her boss, Perrin, allowed her to go, which, as we’ll see, was rare.

In 1874, Bernhardt’s other artistic practices began receiving some acclaim again. Remember I mentioned earlier that she was a good painter? At this point, she began sculpting to come with the boredom she felt at the theater, where she was being denied roles and not getting along with the company. She rented a studio in Montmartre—someday, Picasso would rent the same one—and ordered a white silk pantsuit which she wore as her “bohemian artist” uniform.49 If this sounds like it’s not a big deal, I will remind you that it was literally illegal for women to wear a pantsuit in some places at this time!50 It wouldn’t be until the 1930s that the pantsuit came more into vogue for women, and even then it was still only daring and subversive women who wore them with any regularity. When our old friend Marlene Dietrich wore one in the movie Morocco in 1932, she kissed a woman in the same scene.51 If you want to see Bernhardt in her pantsuit, check out the Substack. And if you want to hear the other times we’ve crossed paths with Marlene Dietrich, check out my old episode on Joe Carstairs.

Not only was she daring, but she was actually quite a talented artist. For twenty-five years she exhibited at the annual Salon and was awarded an honorable mention for a sculpture of an old Breton peasant woman grieving over the corpse of her drowned son.52 The sculpture is called Apres la tempête, meaning “after the storm.” You have to see this sculpture because it’s incredible. The boy’s hair is perfect, it looks like it’s dripping water. Today, it’s housed at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, but I’ve included a photo on the Substack.

In 1874, Bernhardt’s artistic life introduced her to Louise Abbéma, a painter who was well-known in the lesbian circles of Paris. Many biographers never talk about this because even for a life full of scandal, this one is too scandalous! Because Bernhard and Abbéma were—gasp!—lovers! We have evidence of this in very sexy photos they took together, and they expressed their relationship in joint sculptures and other, quote, “artworks that expressed their bond.”53 This included a sculpture of their hands intertwined, which was a very common sculptural theme at the time, but almost always reserved for depicting married couples.54 But contemporary journalists knew because Bernhardt would give them little hints, like posing with a bust of Abbéma that she’d made for all her publicity photos; in fact, I believe that bust is the one in the photo I’ve included in the Substack. There were also society and political cartoons that reveal that people knew about their relationship as much as they knew about Bernhardt’s affairs with men.55 Bernhardt never talked about her affair with Abbéma in the press or in her memoir, but she never talked about her sex life in the press or in her memoir. Remember, the male Comte de Keratry is hardly mentioned in her memoir but we know they had an affair of some sort too.

Even when biographers do mention it, they dismiss this as Bernhardt and Abbéma basically… goofing around? Even Gottlieb sums up their relationship in a single paragraph, dismissing their sexual relationship as Sarah being a really good friend who just wanted to make her friends happy???? Which, what?! I too am a generous friend but I don’t have sex with people I’m not attracted to because of that generosity. What a wild idea! Some people really can’t stand the idea that Bernhardt was attracted to women as well as men, it’s silly. But Bernhardt and Abbéma remained close for nearly fifty years. Bernhardt was good at staying in touch with exes, but of all the flings she had, her relationship with Abbéma had longevity. But I’m sure they were just best friends, right?

Later, she and another lover-turned-friend Gustave Doré produced statues for a casino in Monte Carlo designed by Charles Garnier, the famous opera house designer. Bernhardt’s contribution was a winged figure holding a lyre called Le Chant.

Of course, there were critics and detractors of her artwork. Not only did Perrin, her boss at the Comédie Française, hate that she did anything that he didn’t have control over and that made her more famous than the rest of the company, but there were also several people who suggested that when Bernhardt and her friends left her studio, “more professional hands took over and did the serious work” of creating her art.56 I have a feeling this is just a case of having haters because these accusations were published in anonymous memoirs and if there were any truth to it I think they probably would have called that out in a more serious way.

A few years later, the Comédie Française company went on tour to London, booking the Gaiety Theatre. She had long been butting heads with Perrin because he was very dictatorial and harsh with her and meanwhile Bernhardt was very clearly eclipsing the rest of the company. He tried very hard to make her fall in line, to which Bernhardt’s response was to offer to stay home in Paris; at first, Perrin was fine with this… until the Gaiety theatre started threatening to cancel shows because Londoners only wanted to see Bernhardt, they didn’t care about the rest of the company. Then, while in London, Bernhardt gave some private performances, which everyone did because the Française paid badly, but Perrin came down very hard on her about it.57

So things were not well at work, but London adored her. She was the toast of the town, invited into the homes of the highest-class people in London as a social equal, not as a performer. She reportedly met and befriended many leaders of the English artistic scene, including Oscar Wilde. He was apparently so inspired by her that he would write his famous Salome for her, though it seems like she never got to perform in it, at least not while he was alive.58 Bernhardt also exhibited some of her artwork in London, and Prince Leopold, son of Queen Victoria, apparently purchased one of her paintings to hang in one of his royal residences.59

In the midst of all of that, she was also running around and collecting animals for her notorious private menagerie. While in London she apparently acquired a cheetah, seven chameleons, and a wolf.60 Her menagerie would be a source of fascination about her life for ages—she kept a lynx and an alligator at one point, though apparently she accidentally killed the alligator by feeding it milk and champagne.61 Clearly, she wasn’t keeping a zookeeper on staff.

All in all, the London tour was a huge success... for Sarah. And she was very aware of the difference in reception of her versus the rest of the company. The trappings of a secure job were starting to chafe for her, and then insult was added to injury. Soon after their return to Paris, Perrin wanted Bernhardt to appear in L’Aventurière, a play and role that Bernhardt hated. She told Perrin that she was too exhausted from the tour, and even had a doctor’s note to get out of it, but he forced her to perform anyway. On top of her illness, the play was also under-rehearsed, they’d only done it three times before they opened it to the public. She performed exactly once and then resigned as soon as the bad reviews came out the next day.

To really drive home her point, Bernhardt left Paris as soon as she finished her resignation letter. And she also sent copies of her letter, which placed the blame squarely on Perrin, to newspapers Le Figaro and Le Gaulois, ensuring that all of Paris would know what had happened.62 And also quite possibly ensuring that Perrin would find out from the newspapers before he’d gotten to his office and seen her letter. Bernhardt never lost her flair for the dramatic.

But this opened up a can of worms. The theater sued Bernhardt for breach of contract and won. They were awarded 100,000 francs, which Bernhardt had to pay back, though she regarded the amount as ridiculous and extortionary.63 It took her years to pay off. And no surprise—100,000 francs would be a lot of money today and in 1879 it was a fortune! It was equivalent to about 3 million francs in 2015!64 Funnily enough, in 1907, the Comédie Française suffered a fire and had to do a big fundraiser for repairs and Bernhardt donated—can you guess it?—100,000 francs as a little jab at their history and the money they had extorted from her.65

However, despite her casting all of this as a rash decision, there’s evidence to suggest that she had been planning this resignation a lot longer than anyone guessed. She quit the Française and within a few weeks was back touring in London with a company she claimed to have put together overnight. In fact, a man named Edward Jarrett had approached her even before the London tour with the Française to see if she’d be interested in a solo tour in the United States.66 She would always claim that she rejected the idea when he initially proposed it, but how quickly they managed to put together three new plays and a wholly independent company suggests otherwise.

This England engagement was an enormous success. It proved to Bernhardt that she didn’t need the director of the Comédie Française, that she could truly do it all on her own. She went next to Brussels and Copenhagen, then a “whirlwind tour” of twenty-five French cities in less than a month before embarking for the US in October 1880.67 Tactlessly, Perrin kept sending messengers after her around Europe, trying to scare her back to the Française by suggesting that all this independent touring would destroy her. He couldn’t have been more wrong. Her first tour was an enormous success, and she returned to Europe more famous than ever before and also incredibly wealthy.

That said, there was some backlash among the French after she left the Comédie Française. Some critics really never forgave her, especially because she went and toured the US so soon after; even a hundred years later some French critics will still say that Bernhardt could have been a great actress if only she’d stayed at the Comédie Française.68 Like, okay guys, calm down. Not to worry though, she did eventually win the French back.

It’s with this triumphant return that Bernhardt ends her memoir, My Double Life. She closes the book with the quote,

My life, which I had first expected to be very short, now seemed likely to be very, very long. It gave me great joy to think of the infernal displeasure that would cause my enemies. I resolved to live. I resolved to be the great artist that I wished to be. From the time of my return onward, I dedicated myself to my life.69

And like, I love this. All of this is great—”I dedicated myself to my life” is just a wholesome positive motto for any artist, but that middle part about great joy at infernal displeasure is I think something a lot of us are trying not to say every time we post on Instagram and I love that she just did. She just said it, and I love that.

Bernhardt would end up doing a total of nine US tours, each of them lasting months on end. And she did many more tours around Europe and even parts of Asia. Her health, which had been bad—sometimes even precarious—up until now suddenly improved dramatically once she was freed in her mid-30s. Some have suggested that this is because her earlier health problems were more likely dramatic protests against being bossed around, but I actually wonder how much of this was a real improvement because her stress was reduced.70 We all know that ongoing stress can be very toxic and hard on the body, and I wouldn’t be surprised if reducing that stress actually did help her health improve.

With each tour, her fame increased and she made tons of money. Her great fame and notoriety were of course in part because she was an enthralling performer to watch. It’s worth noting that Bernhardt only ever performed in French, she never tried to perform in another language, but her physicality and gestures were such that audiences could understand her anyway, even if they didn’t speak a word of French. She performed as both men and women. I’ve included a famous clip of her performing as Hamlet in 1900 in the Substack post if you’d like to see it. [It’s further below, where I talk about Hamlet.] I wish I could go through every major character she played, but she played at least seventy roles in her lifetime—she performed on stage for fifty or so years! I’ll mention the highlights from here on out, but if you’re interested in reading more about her theatre career, I believe that there are books out there that focus just on that.

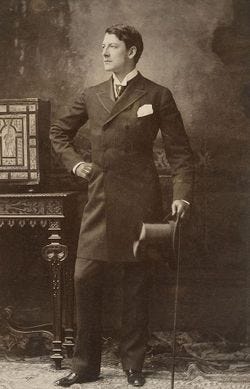

Not only was she an incredible actress she was also a superstar celebrity in a very modern sense—in fact, she was very much a pioneer of what it means to be a modern celebrity. Designers all wanted to work with her, artists portrayed her, and magazines followed everything she did, including filling gossip columns with news about her. She appeared in ads for products, like absinthe,71 makeup,72 and sardines.73 All of them, by the way, played on Bernhardt’s famous tall and thin figure with curly hair. She also developed ongoing partnerships with different artists and designers, sort of like we see today with Keira Knightley with Chanel or Natalie Portman with Dior. Bernhardt frequently wore designs by a designer named Jacques Doucet, and a lot of her jewelry came from Lalique. The famous Art Nouveau artist Alphonse Mucha used Bernhardt as his inspiration for a series of beautiful posters. His first poster of her for Gismonda made him famous, and they continued to collaborate for years. You can also see that in the Substack!

In 1882, when Bernhardt was 38 years old (or maybe 41), she got married to a Greek aristocrat and military officer named Aristides Damala, though he’s often listed as Jacques Damala because Bernhardt convinced him to try his hand at acting and use the stage name Jacques.74 He was a terrible actor by all accounts.

Damala had, quote, “a romantic history as scandalous—and a ruthlessness as strong—as her own.” He was an inveterate gambler, an obsessive womanizer, and often straightup anti-Semitic. Despite this, she impulsively decided to marry him, though they came up against several issues, like the fact that he was Greek Orthodox and she was a Jewish Roman Catholic, and inter-religious marriage was not permitted in France. Also, and more importantly, Damala wasn’t really excited about the idea of marrying Bernhardt, but I guess she was hard to say no to because he accompanied her on a mad dash to London to elope in a Protestant church. Everyone thought this was a terrible idea, including her son Maurice who hated Damala and took to calling him “Monsieur Sarah Bernhardt.”

The whole marriage was a huge mistake. Damala flaunted his mistresses in Bernhardt’s face, even running off to Monte Carlo with one and losing eighty thousand francs gambling in a single night.75 According to one historical currency converter, that is roughly 360,000 euros in 2015.76 He impregnated one mistress, a young pretty extra in one of Bernhardt’s plays, and that woman abandoned their child on Bernhardt’s doorstep!77 Enraged, Bernhardt threatened to have the child drowned in the Seine (surely she wouldn’t have actually done so), but a friend made sure that the baby was adopted by a Greek family and sent to Greece.78 Damala also was severely addicted to opium and appears to have been supplying it to Bernhardt’s sister Jeanne, though perhaps it was the other way around.79 Bernhardt eventually threw him out, but he came back a few years later. By then, his drug addiction had done such damage that she took pity on him, nursing him through his young death in 1889 and the age of thirty-four.80

Bram Stoker, the famous author of Dracula, once met Damala and described him as having “dead eyes and a white waxen face.”81 In fact, in 1897, Stoker acknowledged that Damala was one of his models for Count Dracula.82

After his death, Bernhardt actually did wear mourning clothes for a year, as was Catholic custom, and she never renounced his last name, which she’d hyphenated with her own, though most people just ignore that. For a while, she insisted on being called the widow Damala. She even sculpted a gorgeous funerary bust of him, which to be honest seems more handsome than the real man. To me, it seems like this is what she saw when she looked at him, which is very interesting. I’m telling you, it looks significantly different than known photos of him. Check out the Substack to see what I mean.

Soon after Damala’s death, Bernhardt’s mother died. Jeanne followed not too long after. Her aunt Rosine had disappeared sometime before, never to be heard from again. Bernhardt was distraught by all of these losses, and fell ill for some time before recovering. She was also financially destroyed by Damala’s gambling so as soon as she did recover she went on one of her many tours to restore her bank accounts.

Meanwhile, Maurice had grown up as well. They had nearly always remained close, and she had raised him to be a little aristocrat, quote, “showering on him every luxury and indulgence.”83 As an adult, he grew up to be handsome, poised, elegant, and a superb horseman. But he had become something of an inveterate gambler himself, and Bernhardt was always having to bail him out of debts. Nevertheless, Bernhardt would say, quote, “All I expect from Maurice is to be well-dressed.”84 He eventually got married and had kids, and Bernhardt became a lovely doting grandmother, which I think is very sweet to think about.

There is only one known instance of the two of them falling out—the Dreyfus Affair, which divided all of France. The scandal began in December 1894, when French military officer Captain Alfred Dreyfus was convicted of treason—they said he’d passed French secrets to the German embassy in Paris. It was a baseless accusation, fueled largely by anti-Semitism, but the trial found him guilty. Bernhardt supported Dreyfus, even publicly supporting Émile Zola’s famous article, “J’Accuse…!” She doubled down when evidence started to come to light in 1896 that Dreyfus had been falsely accused. But her son was an anti-Dreyfusard and pro-Army. Gottlieb supposes that it was the cognitive dissonance between his upbringing—raised as a Catholic aristocrat and what he knew to be true about his background as a quarter Jewish—that led him to this opinion.85

The two had a horrible fight over it. Maurice, his wife, and their daughter went to Monte Carlo and didn’t speak to Sarah for over a year. They eventually made up but the name Dreyfus couldn’t be mentioned in the Bernhardt home without sparking off a fight. Even 10 years later, in 1905, the name Dreyfus was mentioned—not even Alfred Dreyfus, a different Dreyfus who had died—and the fight began again, ending in “screams of rage [and dissolving] into farce.”86 Several people were witnesses to this, including Maurice’s daughter, who wrote about it, and Louise Abbéma, who was at dinner that night. Dreyfus was exonerated in 1906 and presumably, the two stopped fighting about it.

A few years later, in 1898 or 1899, Bernhardt bought the old Théâtre Lyrique and it was renamed the Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt. She performed and produced plays there until she died. The theatre is still standing, actually, but today it’s called the Théâtre de la Ville.

The same or the next year, in 1899, Bernhardt decided that she was going to perform Hamlet, as Hamlet. She considered him the icon of tragedy, but she wanted to do it her way. She actually commissioned a new prose version that preserved more of Shakespeare’s original text better than any of the other Hamlet productions of the nineteenth century. Contrary to a lot of interpretations of Hamlet as this anxious hand-wringing teen who doesn’t know what he’s supposed to do once his Dad Ghost instructs him to get revenge, Bernhardt saw Hamlet as, quote, “youthful, masculine, determined: From the moment he concludes that his father was indeed murdered by Claudius, his path is set and it’s only a matter of finding the right circumstance before he takes revenge.”87

A lot of people did not like this interpretation. Bernhard wrote once that in this role, quote, “I am reproached for being too active, too virile. It appears that in England Hamlet must be played as a sad German professor… There are those who are absolutely determined to see in Hamlet a woman’s soul, weak and indecisive; but I see the soul of a resolute, sensible man.”88 I find this to be a really interesting interpretation from her because in the late nineteenth century saying that a man had a woman’s soul was a euphemistic way of saying that a man was gay. And for her to invoke a German professor is especially telling to me because it was German sexologists and theorists who were leading the charge on transforming homosexuality from a crime to a medical diagnosis. This idea of a female soul in a male body was an actual medical diagnosis from leading German sexologist Marcus Hirschfield—he believed that something happened in the womb that would make men have very feminine personalities and that’s why they would grow up to be gay. Hirschfield wasn’t working in obscurity, so I’m sure Bernhardt had heard of his theory, especially considering the circles she ran in. So it’s fascinating to me that she both saw that interpretation of Hamlet and rejected it because I think we’ve come back around to the idea that Hamlet was a sad gay teen. She seems to be saying that, in fact, the English intelligentsia and theatre-goers preferred that interpretation, and that her much more traditionally masculine portrayal was not to their tastes. Which I think is really fascinating.

She first portrayed Hamlet at the theatre that bore her name on May 20, 1899.89 Bernhardt would go on to portray Hamlet I think hundreds of times. One of her earliest film debuts, in 1900, was as Hamlet. Miraculously about a minute of it is preserved—that famous duel with Laertes. Despite being in her fifties by this point, she had achieved a sort of agelessness while she performed, and in the video, it’s totally believable that she is twenty or so.

At the turn of the 20th century, Bernhard was really at the peak of her power. She was a worldwide celebrity and she was fully in charge of her own life. She had lovers, she kept acting, and she began making movies. She followed in the footsteps of the men she’d dated while she was in her twenties and began dating much younger men; most famously was the multi-year affair she began in 1910 with Lou Tellegen, a handsome young actor nearly forty years younger than her. She continued touring, Tellegen usually on stage with her, performing the plays and scenes she preferred most. For decades, every tour was supposedly her last, and theatres would be filled with people wanting to see Sarah Bernhardt perform for the first time or the last.

It’s worth noting that Bernhardt had been on stage long enough to start her career as a pioneer of a new modern acting style, a devotion to realism that had been rare in the generations before her, only to start being described as mannered and old-fashioned by the time her career was coming to a close. People still turned out to see her during her final tours, and they still usually sold out, but it was very much with the understanding that they were seeing something old, a form of art and performance that was going away. What’s that saying, either you die a young hero or you live long enough to see yourself become a villain? I think a similar idea applies here—she went from being avant-garde to a symbol of the old ways. It doesn’t seem like Bernhardt minded this; at least, we have no record of her saying so, though she did try to adapt to new media like movies.

That said, her work in movies wasn’t lauded. Her exaggerated gestures, which played well on stage, didn’t adapt well to film.90 She never really adapted well to film. I think stage presence mattered a lot for her. That said, I’m glad we got some of her acting on film because it means we can see something of what she was doing, though it’s probably nothing like sitting in a theatre in front of her was.

In 1906, Bernhardt returned to the Conservatoire, the place where she’d learned to act all those decades before, for exactly one term. She taught an acting class, but she too much an actress and not a teacher. Gottlieb wrote, quote, “She was so much a lesson unto herself that it wasn’t possible to learn from her example; Sarah Bernhardt was the last, as well as the first, of her kind.”91 She was quickly fired, but she managed to teach a young girl named May Agate, who remembered that Bernhardt didn’t assign exercises or tomes or conventions—Bernhardt simply sat in a chair and lectured to them, illustrating by anecdote. She would, quote, “make the characters into living people for us [the students], giving us the thought behind the words. (‘The author has gotten to write that in,‘ she would often say.)”92 She was trying to teach them to understand human behavior in order to dig into characters, not teaching them to imitate other actors. Clearly, this is what made her great.

In 1914, the French government awarded Bernhardt the Legion d’Honneur, the highest French order of merit both for civilians and the military. It honored her work as an actress and director. To qualify for the award, which has been an active award since Napoleon instituted it in 1802, each recipient needed to have a minimum of 20 years of service plus “good repute.”93 Some suspect that Bernhardt wasn’t given the award sooner because of the many scandals in her life—she was usually beloved, but hardly in “good repute.” It was well-deserved though; her constant global touring had made her something of a cultural ambassador for France, helping ensure that the French were still seen as the center of arts and culture into the twentieth century.

Unfortunately, she had suffered a severe knee injury while on a ship decades before. In 1915 she decided she could no longer live with the pain and decided to have her leg amputated. Her friends and family begged her not to go this far, but Bernhardt usually stuck to a path once she decided on it. She told a, quote, “weeping Maurice that if he couldn’t bear the idea of amputation, she would commit suicide: It was up to him to decide.”94 Again, a lot of people chalk this up to her dramatic personality, but I think there’s something deeper here—there’s a well-established link between chronic pain and suicide. I suspect that Bernhardt was being serious—she literally could no longer live in that much pain.

Her leg was amputated soon after and she recovered well. She gave using a wooden leg a chance but didn’t like it, and she hated crutches even more. She eventually transformed a sedan chair into a litter and was carried everywhere.

In a sort of surprising turn of events, at least to me, people were really fetishistic about Bernhardt’s amputated leg. P.T. Barnum apparently offered to buy her leg or at least pay her to exhibit her leg at the Pan-American Exposition in San Francisco. She apparently cabled back only two words: “Which leg?”95

Everyone assumed she’d retire from acting at this stage, but she refused to quit. Someone questioned the wisdom of this and she said, quote, “There is always a way. You remember my motto ‘Quand même"‘? In case of necessity, I shall have myself strapped to the scenery.”96

And in fact, she returned to acting quite quickly. World War I had already broken out when she had her surgery, and in late 1915 Bernhardt actually performed for the troops—in fact, a lot of people credit her with the idea of performing for the troops, in fact.97 She was in her seventies by this point, and she arranged it all herself—the French government actually tried to stop her, but she hired another young French actress, Béatrix Dussane, to assist her and went on the road. She performed in open marketplaces, deserted châteaux, hospital wards, mess tents, and once a ruined barn—all in front of thousands of soldiers, most of them wounded.98

She also toured the US encouraging the US to join the war effort through a, quote, “propagandistic one-act play.”99 She visited 99 cities in 14 months as part of this mission.100 It’s hard to say whether it worked, exactly, but it certainly increased support for the war in the US. Again, more proof that she was one of France’s most effective ambassadors. It’s also fun and worth noting that on that 14-month tour, Bernhardt performed scenes from The Merchant of Venice, and she would appear as either Shylock or Portia on alternating nights.101 Until the very end she was subverting gender norms.

Again though, Bernhardt is now in her 70s and her health is starting to fail. In 1917 she got really sick while on this tour. She was hospitalized in New York and people really thought she might die. Maurice and the rest of her family set out to New York to be with her, but she pulled through and returned to France in late 1918. She arrived back on French soil on November 11, 1918, the day the Armistice was signed.

Her health never fully recovered though. Probably because she knew it was close to the end, she began dictating her life story and encouraging journalists to write biographies of her; naturally, she told them all contradictory information. She also dictated some reflections on acting, which were published in a book called The Art of the Theatre. The book is long out of print but it is possible to get your hands on a copy if you search for it. Finally, in 1921 Bernhardt also published a novel called Petite Idole, which was a highly idealized and romanticized version of her life.102 While I think most people call this one strictly a fictional account, there are some people who want to believe there is fact meshed in there.

Despite her growing illnesses, Bernhardt wanted to keep acting. The movie La Voyante, meaning the clairvoyant, was being filmed in her house when she succumbed to various illnesses and old age. She died on March 26, 1923. When Bernhardt died, reportedly only two people were at her bedside, her son Maurice and Louise Abbéma.

Sarah Bernhardt’s beath made front-page news around the world for at least a week.103 At her funeral, an enormous crowd walked with her coffin from her home to Pere Lachaise Cemetery, passing by the theatre she owned and pausing for a moment of silence there. Her legacy is really to be a pioneer of female self-determination and autonomy. Professor Marcus pointed out that we have largely grown out of Bernhardt’s acting style, but we’re finally growing into her as a person.104

That is the story of Sarah Bernhardt! I hope you enjoyed this episode! If you did and you are currently in Paris, I really recommend checking out the exhibit about Bernhardt at the Petit Palais; it’s running through August 27, 2023. This has not been an ad, I just really like the Petit Palais. You can let me know your thoughts by following me on Substack, Twitter, and Instagram as unrulyfigures. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks discover the show.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Clark. My research assistant is Niko Angell-Gargiulo. So if you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com. Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

Altschuler, Glenn C. “Sarah Bernhardt’s Dramatic Life, Onstage And Off.” NPR, September 24, 2010, sec. Book Reviews. https://www.npr.org/2010/09/24/129879698/sarah-bernhardts-dramatic-life-onstage-and-off.

Anonymous. “Tobias Healing His Father’s Blindness.” Text. Cleveland Museum of Art, October 31, 2018. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1969.69.

Bernhardt, Sarah. Après La Tempête (After the Storm) | Artwork. 1876. White marble sculpture, 29.5x24x23 inches. National Museum of Women in the Arts. https://nmwa.org/art/collection/apres-la-tempete-after-storm/.

Brennan, Summer. “The Book of the Courtesans, Part 1: Marthe Aguillon.” A Writer’s Notebook (blog), February 3, 2021. https://www.summer-brennan.com/a-writers-notebook/2021/2/1/the-book-of-the-courtesans-marthe-aguillon.

Chéret, Jules. DMC, La diaphane, Poudre de riz, Sarah Bernhardt, 32 avenue de l’Opéra, Paris. 1890. Lithograph. Musée Carnavalet - Histoire de Paris.

Edvinsson, Rodney. “Francs in 1879 to Francs in 2015.” Historical Currency Converter, January 10, 2016. https://www.historicalstatistics.org/Currencyconverter.html.

Gottlieb, Robert. Sarah: The Life of Sarah Bernhardt. Kindle edition. Yale University Press, 2013.

Grande Chancellerie de la Légion d’Honneur. “Award Criteria | La Grande Chancellerie.” Accessed July 20, 2023. https://www.legiondhonneur.fr/en/page/award-criteria/405.

“Jacques Damala.” In Wikipedia, June 23, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jacques_Damala&oldid=1161577975#Legacy.

Jenner, Greg. “Sarah Bernhardt - You’re Dead to Me.” You’re Dead to Me. Accessed July 12, 2023. https://pca.st/e2q39rx2.

Jossot, Henri-Gustave. Publicité pour Arsène Saupiquet. 1897. Lithograph. Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Mélandri, Achille. Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923). c 1877. Photograph. Royal Collection Trust. https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/exhibitions/portrait-of-the-artist/vancouver-art-gallery-vancouver/sarah-bernhardt-1844-1923.

Nagler, Alois M. “Sarah Bernhardt | French Actress & Theatre Icon | Britannica.” In Britannica, July 12, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sarah-Bernhardt.

“Sarah Bernhardt.” In Wikipedia, July 17, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sarah_Bernhardt&oldid=1165859648.

“Sarah Bernhardt - Themes - Gallery - Mucha Foundation.” Accessed July 19, 2023. http://www.muchafoundation.org/en/gallery/themes/theme/sarah-bernhardt.

Tamagno, Nicolas. Affiche Absinthe-Terminus. 1895. Lithograph. Bibliothèque Forney.

“Théâtre de La Ville.” In Wikipedia, March 17, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Th%C3%A9%C3%A2tre_de_la_Ville&oldid=1145147425.

Wright, Jennifer. “Pantsuits for Women Were Once Illegal.” Racked, December 5, 2016. https://www.racked.com/2016/12/5/13778914/pantsuits-history.

FYI: A few of the links in this post are affiliate links. That just means if you click through a buy a book, I’ll get a few cents of profit but it won’t cost any more for you.

Robert Gottlieb, Sarah: The Life of Sarah Bernhardt, Kindle edition (Yale University Press, 2013).

Gottlieb, 11

Greg Jenner, “Sarah Bernhardt - You’re Dead to Me,” You’re Dead to Me, accessed July 12, 2023, https://pca.st/e2q39rx2.

Jenner

Jenner

Gottlieb, 20

Gottlieb, 20

Gottlieb, 21

Gottlieb, 21

Gottlieb, 26

Jenner

Gottlieb, 29

Gottlieb, 41

Gottlieb, 33

Gottlieb, 34

Gottlieb, 34

Jenner

Jenner

Gottlieb, 45

Gottlieb, 46

Gottlieb, 43

Gottlieb, 44

Gottlieb, 44

Gottlieb, 47

Gottlieb, 47

Gottlieb, 47

Gottlieb, 54

Gottlieb, 55

Jenner

Summer Brennan, “The Book of the Courtesans, Part 1: Marthe Aguillon,” A Writer’s Notebook (blog), February 3, 2021, https://www.summer-brennan.com/a-writers-notebook/2021/2/1/the-book-of-the-courtesans-marthe-aguillon.

Gottlieb, 55-6

Gottlieb, 56

Jenner

Jenner

Gottlieb, 58

Gottlieb, 62

Gottlieb, 59

Gottlieb, 60

Gottlieb, 60

Gottlieb, 72

Gottlieb, 73

Jenner

Jenner

Jenner

Gottlieb, 77

Gottlieb, 79

Gottlieb, 108 - this has big Barbie/Ken marketing vibes, doesn’t it? 😂

Gottlieb, 110

Gottlieb, 100

Jennifer Wright, “Pantsuits for Women Were Once Illegal,” Racked, December 5, 2016, https://www.racked.com/2016/12/5/13778914/pantsuits-history.

Wright

Gottlieb, 100

Jenner

Jenner

Jenner

Gottlieb, 104

Jenner

Gottlieb, 150

Achille Mélandri, Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), c 1877, Photograph, c 1877, Royal Collection Trust, https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/exhibitions/portrait-of-the-artist/vancouver-art-gallery-vancouver/sarah-bernhardt-1844-1923.

Gottlieb, 90

Jenner

Gottlieb, 93

Jenner

Rodney Edvinsson, “Francs in 1879 to Francs in 2015,” Historical Currency Converter, January 10, 2016, https://www.historicalstatistics.org/Currencyconverter.html.

Jenner

Gottlieb, 93

Gottlieb, 95

Jenner

Jenner

Jenner

Nicolas Tamagno, Affiche Absinthe-Terminus, 1895, Lithograph, Bibliothèque Forney.

Jules Chéret, DMC, La diaphane, Poudre de riz, Sarah Bernhardt, 32 avenue de l’Opéra, Paris, 1890, Lithograph, Musée Carnavalet - Histoire de Paris.

Henri-Gustave Jossot, Publicité pour Arsène Saupiquet, 1897, Lithograph, Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Gottlieb, 131

Gottlieb, 133

Edvinsson

“Jacques Damala,” in Wikipedia, June 23, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jacques_Damala&oldid=1161577975#Legacy.

“Jacques Damala”

Gottlieb, 133

Gottlieb, 133

Jenner

Gottlieb, 133

Gottlieb, 153

Gottlieb, 153

Gottlieb, 157

Gottlieb, 160

Gottlieb, 145

Gottlieb, 146

“Théâtre de La Ville,” in Wikipedia, March 17, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Th%C3%A9%C3%A2tre_de_la_Ville&oldid=1145147425.

Glenn C. Altschuler, “Sarah Bernhardt’s Dramatic Life, Onstage And Off,” NPR, September 24, 2010, sec. Book Reviews, https://www.npr.org/2010/09/24/129879698/sarah-bernhardts-dramatic-life-onstage-and-off.

Gottlieb, 183

Gottlieb, 184

“Award Criteria | La Grande Chancellerie,” Grande Chancellerie de la Légion d’Honneur, accessed July 20, 2023, https://www.legiondhonneur.fr/en/page/award-criteria/405.

Gottlieb, 172

Gottlieb, 175

Gottlieb, 174

Jenner

Gottlieb, 176

Jenner

Gottlieb, 178

Jenner

Alois M. Nagler, “Sarah Bernhardt | French Actress & Theatre Icon | Britannica,” in Britannica, July 12, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sarah-Bernhardt.

Jenner

Jenner

Share this post