Hi everyone,

I’m so excited to bring you the story of Sylvia Rivera, an incredible queer icon if there ever was one. Rivera was at the Stonewall Uprising (maybe) and she began one of the first-ever US organizations dedicated to advocating for trans rights. Her story is a bit sad, but it gives us good work to aspire to.

🎙️ Transcript

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m going to be covering an icon of trans leadership and activism: Sylvia Rivera.

But before we jump into Rivera’s life and her role in queer history, I want to give a huge thank you to all the paying subscribers on Substack who make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! Each of these episodes takes me nearly 30 hours of work, which means they’ve become a part-time job. So if you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber for just $6/month or $60/year! Contributions help ensure that I will be able to continue doing this work. Becoming a paying subscriber will also give you access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates on the upcoming Unruly Figures book. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

A quick trigger warning before we jump in: Sylvia Rivera’s life has some moments of serious darkness. We’re going to talk about sex trafficking and sexual assault and prostitution as a minor in this episode, a lot of which is tough. But, as Sylvia Rivera’s friend Ehn Nothing wrote, quote, “creating a narrative of revolt against the constraints of civilization gives us a lineage to draw motivation from, to keep us warm when we feel broken under the weight of this miserable world. By understanding ourselves as part of an ongoing war that has been raging for 12,000 years, we dynamite a history that would keep us as either spectators or pawns in a theater created by bosses, politicians, and police. History is a compass.”1

One last note, the term ‘transgender’ was coined in the 1960s, during Sylvia Rivera’s lifetime, but it wasn’t yet in popular use. That didn’t come until the 1990s.2 So Rivera often referred to herself as a drag queen, or a gay boy, and when I quote some of her writing, I’m going to use her language. Later in her life, however, she referred to herself as transgender and as a woman, though, as we’ll see, she didn’t love labels.

Okay, let’s hop in.

Sylvia Rivera was born on July 2, 1951 in New York City. In a 1989 interview, she mentioned, she was born, quote, “at 2:30 in the morning in a taxi cab in the old Lincoln Hospital parking lot. The old queen couldn’t wait.”3 At birth, she was assigned the male gender and named Ray. Her father, a Puerto Rican man, abandoned her and her Venezuelan mother pretty soon after her birth. When she was just three years old, her mother died by suicide. In her short memoir essay, “Queens in Exile, The Forgotten Ones” Rivera speculates that her mother was trying to escape her then-boyfriend’s abuse. He was a drug dealer and when he was high, he would threaten to kill Rivera’s mother and Rivera. Her mother mixed rat poison into milk and drank it; she gave some of the poisoned milk to her child too.4

Rivera and her mother survived long enough to be taken to the hospital. Rivera’s stomach was pumped and she survived. Her mother, however, died 3 days later. Later, when Rivera was grown up, her grandmother said that Rivera’s mother had tried to kill her too because, quote, “she knew I was going to have a hard life.”5

Rivera moved in with her maternal grandmother at this point, and their relationship was always tense. Her grandmother wanted to take in Rivera’s sister, but Rivera’s stepfather had put her up for adoption. It’s unclear to me what became of the girl. According to Rivera’s essay, her grandmother was a “prejudiced…very racist woman.”6 She didn’t like that Rivera’s father had darker skin, and that Rivera did too. Rivera thinks her grandmother did love her, but in a very harsh way. She ensured that Rivera went to good schools, but they were all-white, and she tried to keep Rivera from learning Spanish. This happened in a lot of twentieth-century immigrant homes, unfortunately, especially in particularly racist parts of the US; I have several friends who are first-generation Americans who never learned to speak their parents’ first languages because their parents wanted them to assimilate into US white culture. It seems like this is the impulse her grandmother was trying to follow.

In the fourth grade, Rivera began wearing makeup to school. Her teachers asked if her grandmother knew and she said yes, which was a lie. She said her grandmother, quote, “didn’t know because there was a woman who was taking care of me out on Long Island, and I would put on my makeup on my way to school. I knew I would wear it home and take it off by 5 o’clock without having any problems because there was nobody in the house.”7 This was the beginning of her transition, I guess you could say. Though there’s not really a well-documented moment for when Rivera came out and began identifying as female and using she/her pronouns.

Most of the other students ignored Rivera’s makeup. But one sixth-grader got angry about it, calling her a slur. The two got into a fight, and Rivera was suspended from school for a week.8

If hearing about child sexual abuse is something you’re not in the headspace to listen to, skip the next minute or so.

Rivera’s first sexual experience came when she was just seven years old or so. She doesn’t offer much detail in her memoir, but she writes, quote, “My cousin was baby-sitting me, and I always found him attractive. He offered and I accepted.”9 Within a few years, she started sleeping with another friend from the Lower East Side, but she doesn’t name him. She also mentions that her uncle began prostituting her–well, actually, she says, quote, “I was turning tricks with my uncle for money.”10 To me the phrasing here is vague–it’s unclear to me if her uncle is assaulting her then paying her (remember, she’s under 10 years old at this time, so all sexual encounters she’s having, especially with adults, are by definition non-consensual) or if he’s selling her and splitting the money with her. Either way, it’s not a good home situation.

Worse, the adults in her life seemed to be aware something was going on and didn’t step in. In her essay, quote, “A woman once time [sic] patted me on my ass and said, ‘Huh, your ass is getting big, that means you’re getting pumped,’ and I took offense at that.”11 Her grandmother would beat Rivera as punishment instead of stepping in and stopping anything.

When her grandmother caught her wearing “feminine” clothing, she would also beat Rivera. She’d say, quote, “We don't do this. You're one of the boys. I want you to be a mechanic." Rivera would respond, "No, but I want to be a hairdresser. I want to do this. And I want to wear these clothes."12

I want to point out that a lot of biographies of Rivera leave out this abuse. I don’t know that it’s to protect readers, because they almost always talk about her sex work as a child. I think it’s out of a desire to discredit the link between sexual abuse and quote-unquote, “deviant sexuality,” to use a nineteenth-century term. That link was historically used to discredit homosexuality as natural, saying that it was a crime or an illness that the victims then grew up to perpetrate themselves. I think–hope–that we’ve come far enough and are enlightened enough to take Rivera at her word that the abuse she survived was not why she later was attracted to men or was in any way related to her gender identity. It seems to me that Rivera didn’t even necessarily process these abuses as traumatic events, though she could be glossing over things.

So it’s probably not a surprise that Rivera ran away from home when she was nearly 11 years old. In that same 1989 interview, Rivera mentioned, quote, “The only reason that I left home at such an early age was because my grandmother came home crying one day with the tears [sic] in her eyes.”13 Apparently her grandmother had overheard others calling her Spanish slurs for gay people, and she was upset about it. It’s unclear to me from the interview if she was upset that Rivera was gay or upset that these people were being cruel to her; maybe a little bit of both.

After she ran away, Rivera lived on the street, near Times Square. She made her way to 42nd Street, where she’d heard from her family that the city’s sex workers worked. They would mention it on the subway, mocking the sex workers that got on and off the train at one of the 42nd Street stations. She began turning tricks, in her words, to survive. She mentioned, however, that she was often afraid during this time, and that she, quote, “found [turning tricks] disgusting, though. I used to go home and scrub myself clean.”14

She described that life was, quote, “dangerous on 42nd Street. We all stuck together. The police were constantly chasing us. We had a code: If one of the girls or one of the boy hustlers spotted a cop, word was passed down that “Lily in blue” was coming. This meant we would disappear. So a warning of “Alice in the blue gown” or “Lily” meant to disperse.”15

Once out of the house, Rivera was able to start fashioning her own identity without interference from family, though she still had to contend with police. “I was an effeminate gay boy. I was becoming a beautiful drag queen, a beautiful drag queen child.”16 She was adopted by a couple of drag queens that were older than her and showed her how life on the streets worked.

In her essay, Rivera mentions that there was a social difference between what she called “street queens” and crossdressers at the time. Quote, “I didn’t even know what cross-dressers were until much later. The street queens have always been prostitutes to survive, because some of us left home so early, or it just wasn’t feasible to be working if you wanted to wear your makeup and do your thing.”17 From her experience, it seems, crossdressers wore quote-unquote “feminine” clothing when it was safe to; but queens like Rivera wore “feminine clothing” all the time.

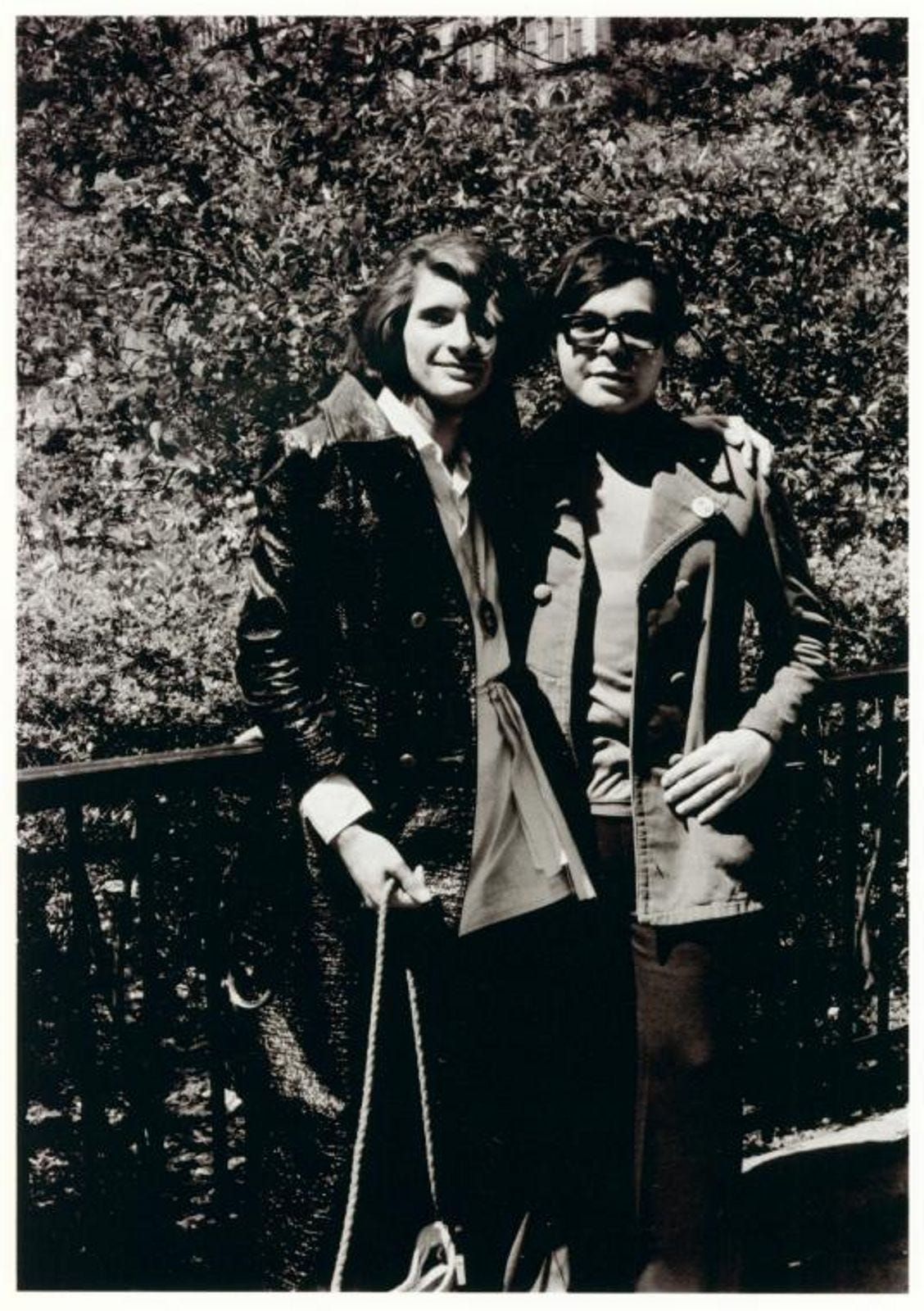

About a year after she left home, Rivera met Marsha P. Johnson. Their names are often intertwined in history, but I had no idea until researching this episode that Rivera was only 11 at the time, and that Johnson was 18. When they met, quote “a very strong sistership was born.”18 Johnson took Rivera out to eat. Johnson took Rivera under her wing, and the two would hang out and talk politics and liberation. Rivera later said of Johnson, quote, “she was like a mother to me.”19

At the time, Rivera’s living situation was precarious. She was, quote, “roaming from house to house, or I’d stay in the hotel room the trick would rent.”20 This is how it was for a lot of unhoused folks in the queer movement. Without the ability to get a good job–and Rivera was too young to get a job even under the much looser child labor laws of the 1960s–people couldn’t afford rent so we see a lot of shared living spaces being rented illegally. People would also throw rent parties where every attendee contributed whatever they could. Rivera wrote, quote, “you helped somebody out and you might end up crashing there some time.”21 But for the most part, they stayed indoors all day, hiding from the police.

Rivera had begun drinking alcohol at around 8 years old. But living on the street was when she started using other, harder, drugs. In her essay she mentioned trying everything except ecstasy. This experimentation would later lead to severe addiction, and Rivera had trouble getting sober until the last two years of her life.

Rivera’s life during the mid-1960s is unclear. It seems like she lived with Marsha P. Johnson and some others in an apartment on 44th Street. Johnson was always ready to take in anyone who needed a place to stay at that time, and Rivera seems to have learned a lot about activism and mutual aid from Johnson. We know she got arrested for “loitering with the intention of prostitution” numerous times, but the charges were always dropped.22 She would maybe spend a night in jail, and her grandmother would always bail her out though.23 It seems like the two remained in touch, even though Rivera wasn’t living at home anymore.

Rivera managed to escape actual prostitution charges because she had a good eye for who was a cop and who was a genuine john. She could clock law enforcement and would refuse to get in their cars; her friends though, even Johnson, wouldn’t believe her instincts and many of her friends got arrested after getting in the car with cops disguised as clients after Rivera had already turned them down. She did almost get caught by someone, but she managed to jump out of the vehicle first.24

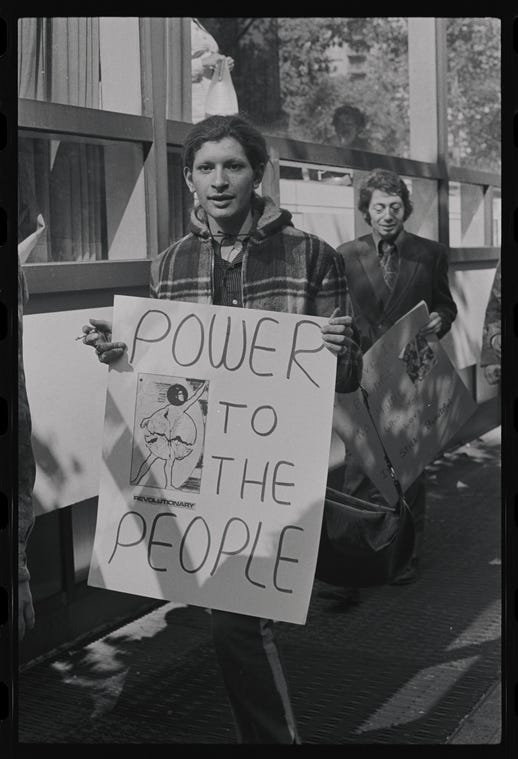

It also seems that Rivera was already leading an activist lifestyle. In “Queens in Exile,” she mentioned, quote, “I had been doing work in the civil rights movement, against the war in Vietnam, and for the women’s movement.”25 I haven’t seen much detail on this, so I’m not sure how involved she was or what demonstrations she was attending. But she was there, and it seems like her work there inspired some of her work for LGBTQ rights.

In June 1969, New York City was tense. It was hot and humid and the morality police were cracking down everywhere. On June 28, the Stonewall Inn uprising began. I talk a lot about Stonewall in episode 14 on Stormé DeLarverie. Stormé was the person who threw the first punch when the police raided the place and the riots began. But both Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera were also present, despite the fact that Stonewall was not a drag bar. In fact, Rivera was careful to point out that Stonewall Inn was a gay bar owned by the mafia. She wrote, quote, “It was a white male bar for middle-class males to pick up young boys of different races. Very few drag queens were allowed in there, because if they had allowed drag queens into the club, it would have brought the club down.”26 For queens to get in, they had to know a drug dealer inside. The main drag bar at that time was the Washington Square Bar on Third Street and Broadway, so that’s where Rivera hung out more often than Stonewall.

Episode 14: Stormé DeLarverie

Listen now (20 min) | Thanks for subscribing! Your subscription helps fund my research, as well as food and coffee. Not a subscriber yet? Subscribing gets you ad-free episodes right in your inbox, and it supports independent research and publication. Subscribe here. You can also listen to Unruly Figures on

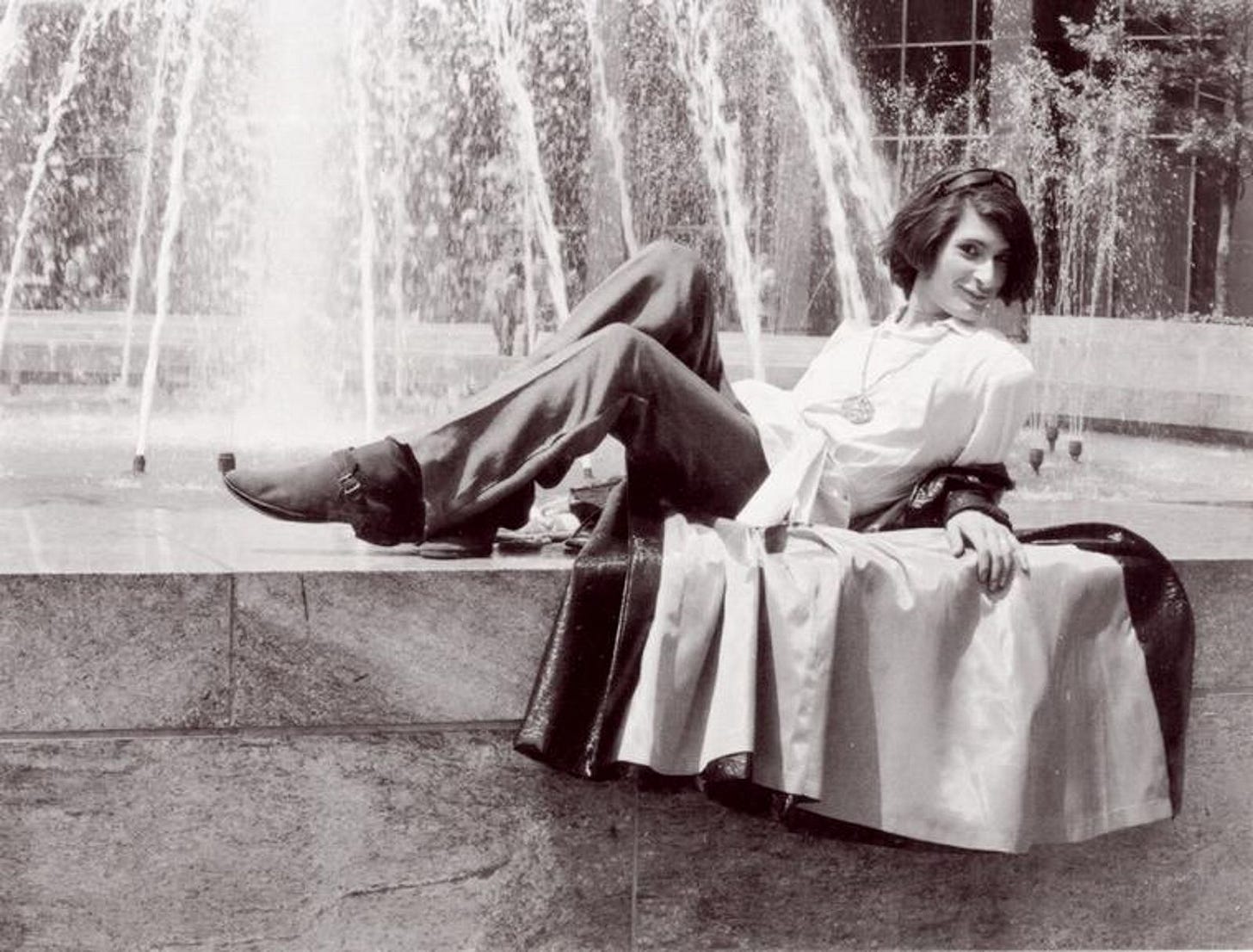

But Rivera was at Stonewall Inn that night, having a drink with her partner at the time. It was apparently the very first time she’d ever been there.27 She mentions that she was, quote, “wearing a woman's suit. Bell bottoms were out then. I had made this fabulous suit at home and I was wearing that and I had the hair out. Lots of makeup, lots of hair.”28

The Mafia, who owned Stonewall, had paid off the police already that week, but it didn’t matter. Inspector Seymour Pine, who ran the raid that night, was there because he was trying to clean up morals inside the police force. He was trying to end the Mafia protections in addition to ending prostitution in general and cracking down on queer folks. As I mentioned in episode 14, the police checked to see if all the patrons were wearing appropriate clothing. They had to be wearing three articles of clothing that matched their biological sex and if they weren’t they could be arrested.

Rivera remembers that after being checked and cleared, quote, “usually we’d go somewhere and have coffee and come back in 15, 20 minutes. The padlock was cut off, and it was back to business - drinking watered-down booze, buying drugs, and dancing.”29 But that night everyone congregated, remaining as the raid continued. Patrons were fed up and frustrated with ongoing persecution from the police.

In the 1989 interview, Rivera mentioned that it was like everyone’s frustration coalesced at once. She described the scene as, quote,

everybody just like, Alright, we gotta' do our thing. We're gonna' go for it. And when they ushered us out, it was nice, you know, when they just very nicely put you out the door. And then you're standing across the street in Sheridan Square park and, but why? Buy why? All of a sudden you just feel this...everybody's looking at each other. But why do we have to keep on constantly putting up with this?30

Of her role there, Rivera was long believed to be the person who threw the first molotov cocktail. She disputed this in another interview, but she did say she threw the second.31 Apparently, “for six nights, the 17-year-old Rivera refused to go home or to sleep, saying “I’m not missing a minute of this—it's the revolution!”32

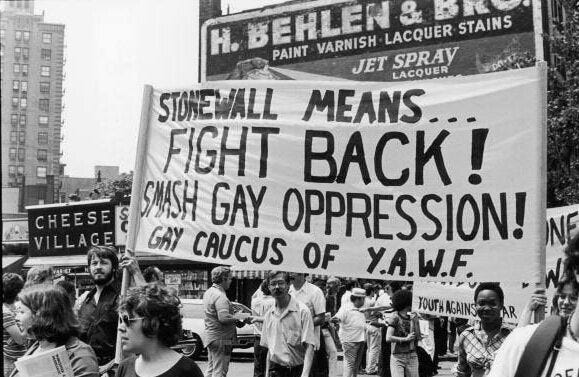

Stonewall is seen as the ignition point for the modern LGBTQ movement. The first Pride parades began the very next year, but Rivera and other trans folks were told to not participate. This began a long, and to some extent ongoing, clash between trans activists and gay rights activists. Throughout the 1970s, Rivera faced gay rights leaders who left transgender people out of their advocacy work. The Gay Activist Alliance (GAA), which formed in response to Stonewall, explicitly rejected the role transgender people had played in Stonewall.

Despite that, Rivera initially joined the alliance and started attending meetings. At the very first one they told her she needed to sign up with her deadname, Ray, which she called “a setback” right away.33 She stayed though, because, quote, “I liked the idea that we, as an organization, were going to change the world. And there was a place for us. I fell right into the grand scheme of things.”34

I covered Stonewall a lot in that episode I mentioned, but if you’re interested in learning more about the event itself, I really recommend checking out the book Stonewall by historian Martin Duberman. It’s also worth noting that Duberman and another historian, David Carter, believe that Rivera was not at Stonewall when the Uprising began, but joined later, after she heard the news of what was happening. Carter especially notes several inconsistencies in her account, and Duberman apparently considers Rivera, quote, “wildly unreliable.”35 For evidence, Carter notes that another gay activist, Doric Wilson, once witnessed Johnson and Rivera discussing Stonewall; apparently Johnson said, quote, “You know you weren’t there,” and Rivera went quiet.36 It’s a third-hand anecdote, but since there isn’t a lot of footage or photographs of the initial [night of the] Uprising this is the kind of evidence we have to go on.

That said, a lot of accounts from that night are inconsistent, and I think that comes down to a few things–time passing and memories reshaping, for one, alcohol and drug use, for another. But also I think part of it is that people were still afraid of admitting to violence during earlier interviews. It was one thing to say in 2001 what you did back in 1969; it was a different thing to admit to it in 1970 when the statute of limitations on those crimes hadn’t run out yet. The people who fought the police at Stonewall were running a big legal risk on top of drinking at a Mafia-owned bar and dressing against their sex and potentially doing sex work. Assaulting a police officer was a big crime then and now. I’m not saying Carter and Duberman are wrong–Duberman especially interacted with Rivera a lot during her lifetime. I’m just saying there might be something going on other than lying or glory-seeking here, which seems to be the idea that people get about Rivera when they hear that she might not have actually been at Stonewall. I’m not saying that Carter or Duberman are claiming that about her either, for the record, I’m just trying to cover all our bases here.

On April 15, 1970, Rivera was petitioning on 42nd street as part of GAA. There was a demonstration against the war in Vietnam nearby, which the police had come to disperse, when they found her. Two cops told her that she had to leave too because petitioning without an American flag was illegal. She knew this wasn’t true, but they insisted and then arrested her for continuing to petition. She considered that arrest the beginning of her activist career. She remembered, quote, “I didn’t consider that night at Stonewall to be so important out of all the other movements going on. Getting that first arrest for something that I believed in was...wow, what a rush!”37

After she bailed herself out of jail, she went and told members of the GAA what had happened. They did a press conference about it, and seemed set to make Rivera into something of a star over her arrest. But it seems like things started to come to a head about whose rights they were fighting for. Rivera left soon after, because she realized that they were not fighting for trans people.

In her memoir, Rivera wrote, quote,

The reason we, right now, as a trans community, don’t have all the rights they have is that we allowed them to speak for us for so many damn years, and we bought everything they said to us: “Oh, let us pass our bill, then we’ll come for you.” Yeah, come for me. Thirty-two years later and they’re still coming for me. And what have we got? Here, where it all started, trans people have nothing.38

Throughout the early 1970s, Rivera crossed paths with other revolutionary New Yorkers. She joined and supported the New York chapter of the Young Lords, a revolutionary Puerto Rican group. In 1971, in Philadelphia, she met Black Panther Party leader Huey P. Newton at the Peoples' Revolutionary Convention. I’m not sure how often they interacted after that, but it seems like Rivera came away with a positive impression of Newton.39

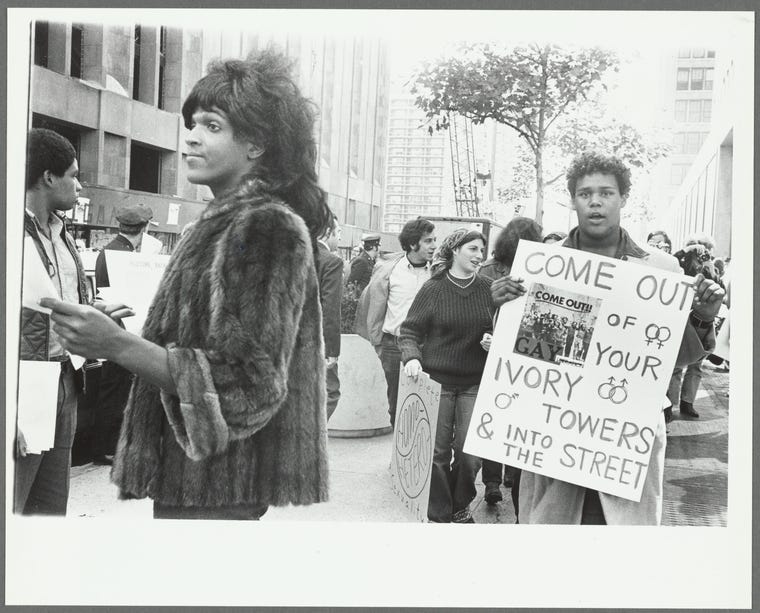

In September of 1970, Rivera took part in the often-forgotten Weinstein sit-ins. New York University had previously been allowing groups like the Student Gay Liberation Front to use Weinstein Residence Hall recreation centers for queer dance fundraisers. Apparently around 400 people were attending these events at NYU.40 Then, suddenly, NYU pulled the plug on these events. Despite having had some previous involvement with the LGBTQ community, NYU allegedly wanted to sever public ties, quote, “until a panel of ministers and psychologists determined whether homosexuality was ‘morally acceptable.’”41

So the sit-ins began, apparently led by Rivera and Johnson.42 NYU quickly threatened to expel any students involved in the sit-in, but the students got involved anyway. Quote, “The sit-ins had showers, amenities and informal teach-ins for students curious about why mostly non-NYU students were occupying the space.”43 The students called home, telling their parents what was happening in excited tones.

The sit-in ended in violence. The NYU student newspaper, Washington Square News, reported in 1970, quote, “NYU security guards first locked the doors of the room and then opened them to let about 50 TPF (Tactical Patrol Force) cops in helmets with clubs into the room.”44 The protestors were violently ejected from the room.

Despite the unhappy ending, Rivera was inspired by the sit-in. She realized during the occupation that queer, trans, and straight people were living peacefully together in the basement as part of the demonstration–and that they could continue doing that. Until this moment, they had been cobbling together housing for unhoused folks in the community. She wrote, quote, “there were so many of us living together, with Marsha and myself renting two rooms and the hotel room, and even then we still didn’t have enough room to house people.”45 So she got to work.

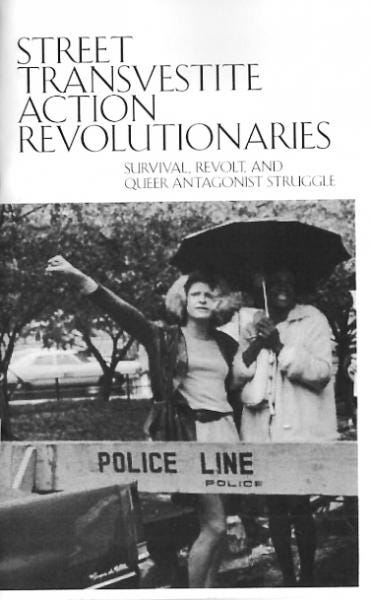

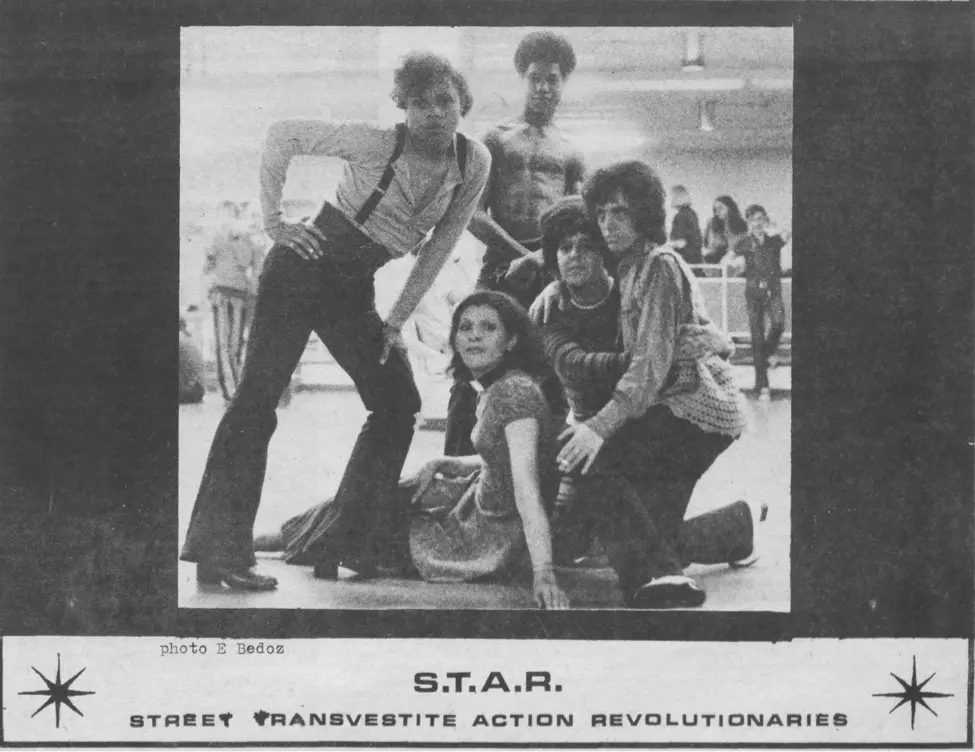

In 1971, Rivera and Johnson worked together to start the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). Today ‘transvestite’ is a derogatory term, but it was still acceptable then. They also opened STAR House–lodgings for trans youth who needed it, directly inspired by the Weinstein sit-ins. The building was located at 213 E. 2nd street between Avenues B and C.46

It was incredibly significant because it was the first organized activist group for transgender rights. “We raised a lot of hell back when STAR first started, even if it was just a few of us,” Rivera wrote.47 Rivera and Johnson raised some money and rented the building from the Mafia. Rivera remembered, quote,

You can say anything you want about the Mafia - yes, they took advantage of us, but when we needed them, they were there. [...] They got us a building for $300 a month. They were there for us. Marsha and I and Bubbles and Andorra and Bambi kept that building going by selling ourselves out on the streets while trying to keep the children off the streets. And a lot of them made good. A lot of them went home. Some of them I lost; they went to the streets. We lost them, but we tried to do the best we could for them.48

Though she was just 19 years old, Rivera became a, “mother” to other queer youth who were unhoused, much like Johnson had been to her. But it wasn’t just their lives she was impacting. Rivera later noted how significant STAR house was to the rest of the neighborhood. She wrote, quote,

The house was well-supplied, the building’s rent was paid, and everybody in the neighborhood loved STAR House. They were impressed because they could leave their kids and we’d baby-sit with them. If they were hungry, we fed them. We fed half of the neighborhood because we had an abundance of food the kids liberated. It was a revolutionary thing.49

STAR really sought to protect people–especially trans youth–from violence against queer bodies in New York. There were a lot of violent attacks on anyone who was visibly queer, many of which resulted in deaths that were never really investigated. STAR House not only gave people a safe place to rest but also a community and affirmation.

Unfortunately, STAR House was short-lived. They were evicted from the house just eight months after moving in; though it’s unclear why.50 The organization itself folded in 1973, probably due to funding issues, though a lot of people also credit the falling out with the larger gay community instigated by the 1973 Pride events. There’s a lot more content out there about STAR and other queer movements in New York in the seventies–I recommend The Gay Liberation Youth Movement in New York: An Army of Lovers Cannot Fail by Stephan Cohen if you’re interested in learning more.

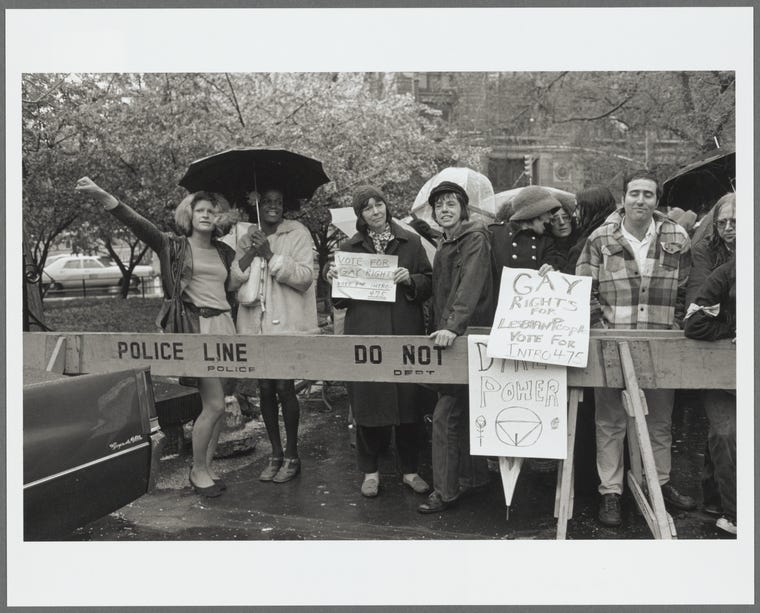

In 1973, Rivera participated in the Pride Parade, but her speaking engagement in Washington Square Park was canceled after months of planning. According to her memoirs, it was because several lesbians had complained about the transwomen, saying that they were, quote, “a threat and an embarrassment to women because lesbians felt offended by our attire, us wearing makeup.”51 Rivera seems to have remained very upset about this for the rest of her life; her memoirs written in 2001 or so still ring with the anger and betrayal she felt then. She called the event, quote, “a brutal battle on the stage.”52 Somehow, Rivera managed to grab the microphone and say, quote, “If it wasn’t for the drag queen, there would be no gay liberation movement. We’re the front-liners.”53 She was booed off the stage.

In 1974, Rivera attempted suicide. Johnson took her to the hospital and spent time helping her get better. Though a lot of people mark this as the only attempt Rivera made, in her own memoir she writes, quote, “Some higher power has been watching me cause I’ve tried to off myself at least six or seven times. It just wasn’t meant to be.”54 Following this, Rivera heavily stepped away from activism, swearing that she wanted nothing to do with LGBTQ politics or the community.

After this, a lot of Rivera’s life is unclear. She was unhoused on and off throughout the eighties and struggled with drug abuse. She was with someone named Frank for about 15 years. It seems like maybe she moved to New Jersey and was working there for a while, though I’m not really sure what she was doing.

On July 6, 1992, Marsha P. Johnson’s body was pulled from the Hudson River, near Christopher Street. Rivera was devastated by this death. In fact, Rivera noted that after her suicide attempts, Johnson had made her promise that, quote, “we would cross the Jordan together.”55 The two had remained close throughout the 70s and 80s, though Rivera mentioned that Johnson’s mental health had severely declined by the 1990s. Nevertheless, Rivera maintained until her death that Johnson did not die by suicide but was in fact murdered.

Johnson’s death did bring Rivera back to the city though. In 1994, she was given a place of honor in the 1994 Pride March. In an interview with the New York Times, she said, quote, “the movement had put me on the shelf, but they took me down and dusted me off...Still, it was beautiful. I walked down 58th Street and the young ones were calling from the sidewalk, 'Sylvia, Sylvia, thank you, we know what you did.'”56

But in 1995, Rivera attempted suicide again. She, her partner Frank, and their cat Isis had been unhoused for a while at this point, and one morning all of their stuff disappeared. They had been kicked out of a shared living situation that Rivera had helped establish, sort of like the apartments Marsha P. Johnson had helped fund on 44th street before Stonewall. Feeling hopeless by the repeated betrayals of the LGBTQ community, she went down to the river, near where Johnson’s body had been found. She attempted to walk into the Hudson, explicitly echoing Johnson’s death.57 After, she stayed in the psychiatric hospital in St. Joseph’s Hospital. From there, she mentioned, quote, “It would be great if the movement took care of its own. But don’t worry about Sylvia.”58

After she was released from the hospital, Rivera remained unhoused. At one point she was living on a pier; a famous video interview with Randy Wicker from 1995 shows her life there. Rivera was truly broke at this point–she’d lost her welfare and Medicaid benefits and wasn’t sure why. She didn’t really have anyone else to rely on.

This is a pattern we unfortunately see in a lot of revolutionary movements. The Civil Rights Movement did something very similar to Rosa Parks, which we talked about in part two of her story. Someone like Rosa Parks or Sylvia Rivera does a lot of the dangerous work up front, but then gets left behind as the movement become more mainstream and more, quote-unquote, “acceptable.”

Episode 5: Rosa Parks, Part 2

Listen now (55 min) | Thanks for subscribing! Your subscription helps fund my research, as well as food and coffee. Not a subscriber yet? Subscribing gets you ad-free episodes right in your inbox, and it supports independent research and publication. Subscribe here. You can also listen to Unruly Figures on

A couple of years later, Rivera moved into Transy House, which was modeled off of STAR House, in Park Slope, Brooklyn. It was more focused on direct aid than political work, though they did lobby for trans rights and the legalization of medical marijuana for cancer patients. I’m not sure, but it seems like maybe Rivera had already been diagnosed with liver cancer by this point. Of Transy House, Rivera wrote, quote,

It’s a communal house run by Rusty [Mae Moore] and Chelsea [Goodwin]. [...] Chelsea was one of my original children at STAR House. It’s a safe house for girls who are still working the streets. It gives them a roof over their heads without having to hustle for money. They pay $50 a week if they can afford it. If not, they help out around the house. One girl cleans up for her board. The only rules are no drugs and no business done on the premises by working girls. And one of the political things we do is lobby for the legalization of medical marijuana for cancer patients and AIDS patients, along with the struggle for transgender rights.59

It was at Transy House that Rivera met her final partner Julia Murray.60 They were together for five years.

As late as June 2001, Rivera was still marching in Pride parades and advocating for trans rights. She passed away on February 19, 2002, from liver cancer. She was just 50 years old. Her partner, Julia Murray was with her at the time of her death.

Today, Sylvia Rivera’s legacy has inspired organizations like the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, which provides free or low-cost legal counsel to low-income or people of color who are transgender, intersex and/or gender non-conforming. In 2005, the cross streets of Christopher Street and Hudson Street in Greenwich Village, two blocks from the Stonewall Inn, was renamed Sylvia Rivera Way. In 2015, a portrait of Rivera was added to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, making her the first trangender person to be included in the collection.

Not long before she died, Rivera reflected on the fact that she never had gender-affirming surgery. She said, quote,

I thought about having a sex change, but I decided not to. I feel comfortable being who I am. That final journey many of the trans women and trans men make is a big journey. It’s a big step and I applaud them, but I don’t think I could ever make that journey… I’m tired of being labeled. I don’t even like the label transgender. I’m tired of living with labels. I just want to be who I am. I am Sylvia Rivera. Ray Rivera left home at the age of 10 to become Sylvia. And that’s who I am. [...] I’m living the way Sylvia wants to live. I’m not living in the straight world; I’m not living in the gay world; I’m just living in my own world with Julia and my friends.61

That is the story of Sylvia Rivera! I hope you enjoyed this episode! If you did, please tell a friend about it. You can also let me know your thoughts by following me on Twitter and Instagram as unrulyfigures. To see photos related to today’s episode, and to get amazing bonus content, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com. And f you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks find this work. Thanks for listening!

📚 Bibliography

Blakemore, Erin. “How Historians Are Documenting the Lives of Transgender People.” History, June 24, 2022. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/how-historians-are-documenting-lives-of-transgender-people.

Carter, David. “Exploding the Myths of Stonewall – Gay City News,” June 27, 2019. https://gaycitynews.com/exploding-the-myths-of-stonewall/.

Dunlap, David W. “Sylvia Rivera, 50, Figure in Birth of the Gay Liberation Movement.” The New York Times, February 20, 2002, sec. New York. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/02/20/nyregion/sylvia-rivera-50-figure-in-birth-of-the-gay-liberation-movement.html.

Kaufman, Michael T. “TimesMachine: May 24, 1995 - NYTimes.Com.” New York Times, May 24, 1995, sec. About New York. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1995/05/24/289195.html?pageNumber=25.

Lau, Jacob Roberts. “Between the Times: Trans-Temporality, and Historical Representation.” University of California, Los Angeles, 2016. UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3js3t1s5.

Nothing, Ehn. “Introduction: Queens Against Society.” In STREET TRANSVESTITE ACTION REVOLUTIONARIES: SURVIVAL, REVOLT, AND QUEER ANTAGONIST STRUGGLE, 3–11. Untorelli Press, 2013. https://transreads.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2019-03-17_5c8dc8507f026_STARcopy.pdf.

Raj, Roshni. “NYU Remembers 50th Anniversary of Weinstein Occupation Today.” Washington Square News, September 25, 2020, sec. New York City. https://nyunews.com/news/2020/09/25/weinstein-occupation-nyu-50-anniversary/.

Randy Wicker Interviews Sylvia Rivera on the Pier, 2012. https://vim eo.com/35975275

Rivera, Sylvia. “Queens in Exile, the Forgotten Ones.” In STREET TRANSVESTITE ACTION REVOLUTIONARIES: SURVIVAL, REVOLT, AND QUEER ANTAGONIST STRUGGLE, 40–55. Untorelli Press, 2013. https://transreads.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2019-03-17_5c8dc8507f026_STARcopy.pdf.

———. Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries. Interview by Leslie Feinberg, 1998. Workers World. https://www.workers.org/2006/us/lavender-red-73/.

———. STREET TRANSVESTITE ACTION REVOLUTIONARIES: SURVIVAL, REVOLT, AND QUEER ANTAGONIST STRUGGLE. Untorelli Press, 2013. https://transreads.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2019-03-17_5c8dc8507f026_STARcopy.pdf.

Rothberg, Emma. “Sylvia Rivera.” National Women’s History Museum (blog), March 2021. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sylvia-rivera.

Schreiner, Maggie. “An Army of Lovers Cannot Lose: The Occupation of NYU’s Weinstein Hall.” Researching Greenwich Village History (blog), December 14, 2011. https://greenwichvillagehistory.wordpress.com/2011/12/14/an-army-of-lovers-cannot-lose-the-occupation-of-nyus-weinstein-hall/.

Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson: Listen to the Newly Unearthed Interview with Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries | New-York Historical Society. WBAI, 1970. https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/gay-power-is-trans-history-street-transvestite-action-revolutionaries.

Sylvia Rivera Discusses the Stonewall Riots in a Never-Heard-Before Interview with Journalist Eric Marcus, 1989. https://www.out.com/out-exclusives/2016/10/13/sylvia-rivera-discusses-stonewall-riots-never-heard-interview-exclusive.

Ehn Nothing, “Introduction: Queens Against Society,” in STREET TRANSVESTITE ACTION REVOLUTIONARIES: SURVIVAL, REVOLT, AND QUEER ANTAGONIST STRUGGLE (Untorelli Press, 2013), 3–11, https://transreads.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2019-03-17_5c8dc8507f026_STARcopy.pdf.

Erin Blakemore, “How Historians Are Documenting the Lives of Transgender People,” History, June 24, 2022, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/how-historians-are-documenting-lives-of-transgender-people.

Sylvia Rivera Discusses the Stonewall Riots in a Never-Heard-Before Interview with Journalist Eric Marcus, 1989, https://www.out.com/out-exclusives/2016/10/13/sylvia-rivera-discusses-stonewall-riots-never-heard-interview-exclusive.

Sylvia Rivera, “Queens in Exile, the Forgotten Ones,” in STREET TRANSVESTITE ACTION REVOLUTIONARIES: SURVIVAL, REVOLT, AND QUEER ANTAGONIST STRUGGLE (Untorelli Press, 2013), 40-55, https://transreads.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2019-03-17_5c8dc8507f026_STARcopy.pdf.

“Queens in Exile,” 40

“Queens in Exile,” 40

“Queens in Exile,” 41

Emma Rothberg, “Sylvia Rivera,” National Women’s History Museum (blog), March 2021, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sylvia-rivera.

“Queens in Exile,” 41

“Queens in Exile,” 41

“Queens in Exile,” 41

Rivera and Marcus Interview

Rivera and Marcus interview

“Queens in Exile,” 42

“Queens in Exile,” 42

“Queens in Exile,” 42

“Queens in Exile,” 43

“Queens in Exile,” 44

Rothberg

“Queens in Exile,” 42

“Queens in Exile,” 42

“Queens in Exile,” 45

Rivera and Marcus interview

“Queens in Exile,” 46

“Queens in Exile,” 48

“Queens in Exile,” 49

Rivera and Marcus interview

Rivera and Marcus interview

“Queens in Exile,” 49

Rivera and Marcus interview

Rothberg

Rothberg

“Queens in Exile,” 50

“Queens in Exile,” 50

David Carter, “Exploding the Myths of Stonewall – Gay City News,” June 27, 2019, https://gaycitynews.com/exploding-the-myths-of-stonewall/.

Carter

“Queens in Exile,” 51

“Queens in Exile,” 51

Sylvia Rivera, Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, interview by Leslie Feinberg, 1998, Workers World, https://www.workers.org/2006/us/lavender-red-73/.

Roshni Raj, “NYU Remembers 50th Anniversary of Weinstein Occupation Today,” Washington Square News, September 25, 2020, sec. New York City, https://nyunews.com/news/2020/09/25/weinstein-occupation-nyu-50-anniversary/.

Maggie Schreiner, “An Army of Lovers Cannot Lose: The Occupation of NYU’s Weinstein Hall,” Researching Greenwich Village History (blog), December 14, 2011, https://greenwichvillagehistory.wordpress.com/2011/12/14/an-army-of-lovers-cannot-lose-the-occupation-of-nyus-weinstein-hall/.

Raj

Raj

Raj

“Queens in Exile,” 52

Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson: Listen to the Newly Unearthed Interview with Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries | New-York Historical Society (WBAI, 1970), https://www.nyhistory.org/blogs/gay-power-is-trans-history-street-transvestite-action-revolutionaries.

“Queens in Exile,” 54

“Queens in Exile,” 52

“Queens in Exile,” 53

New-York Historical Society

“Queens in Exile,” 53

“Queens in Exile,” 53

Rothberg

“Queens in Exile,” 43

“Queens in Exile,” 44

Michael T Kaufman, “TimesMachine: May 24, 1995 - NYTimes.Com,” New York Times, May 24, 1995, sec. About New York, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1995/05/24/289195.html?pageNumber=25.

Kaufman

Kaufman

“Queens in Exile,” 55

David W. Dunlap, “Sylvia Rivera, 50, Figure in Birth of the Gay Liberation Movement,” The New York Times, February 20, 2002, sec. New York, https://www.nytimes.com/2002/02/20/nyregion/sylvia-rivera-50-figure-in-birth-of-the-gay-liberation-movement.html.

“Queens in Exile,” 47

Share this post