Hi everyone!

Today I’m so excited to bring you the story of Lucy Schell. She was the first-ever female Grand Prix team manager, and in the 1938 season, she fielded a revolutionary car driven by a talented Jewish driver to beat the Nazis. I can’t wait for y’all to hear more about this underdog win.

A quick note before we hop in—I’ll be in New York this weekend on a research trip, so I won’t be putting out one of everyone’s favorite history in the news posts on Sunday. Sorry y’all! Those will resume next week when I’m back in town.

🎙️ Transcript

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m covering Lucy Schell, the heiress-turned-race car driver whose team beat the Nazis. If you’re into Formula One, this episode is definitely for you, because the roots of that racing circuit are hidden here. For this episode, I’m relying heavily on the 2020 biography of Schell by Neal Bascomb, which I really recommend checking out if you find this episode interesting. He really dives into the history of car racing in Europe in ways that I won’t go into this episode.

But before we jump into Lucy’s life and how she became a powerful race car team owner in France, I want to give a huge thank you to all the paying subscribers on Substack who make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t be possible without you! If you want to support Unruly Figures and my mission to make interesting history free, you can do that at unrulyfigures.substack.com Becoming a paying subscriber will also give you access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes info on the podcast.

All right, let’s hop back in time.

Lucy O’Reilly was born in Paris, France on October 26, 1896. Her father, Francis O’Reilly had become wealthy through a construction business in Pennsylvania. His family had emigrated from Ireland to the United States during the Great Famine (often referred to as the Irish Potato Famine outside of Ireland). Francis met Lucy’s mother, Henriette Roudet while living in France in the 1890s. Possibly he was there on business, I’m not entirely sure. Soon after Lucy was born, they moved back to the US.

One thing that was interesting to me in learning about her was that this very international background gets translated into strange labels for Lucy’s nationality and origin. Several called her Irish-American, some French-American, and a few just American. Almost no one refers to her as solely French, which is strange to me because her mother was French, she was born in France, and as we’ll see she spent most of her life in France. Certainly, the largest and most well-known part of her adulthood was lived in France. That her father’s heritage is privileged when talking about her is…noteworthy, I guess. It stuck out to me as strange.

Of course, this is also at least in part because when asked which country she swore allegiance to, Lucy answered, “I am American.”1 Whether this happened just once or multiple times is unclear. And it should be noted that she answered this way on the eve of World War I when she was fleeing Europe to the US. So…yeah. It’s just interesting. The reality was that throughout her early life, her family had split their time between both continents and Lucy “never felt completely at home anywhere.”2 Meanwhile, Anthony Blight wrote of her in The French Sports Car Revolution, quote, “she remained unmistakably Irish both in looks and temperament, combining a natural charm and vivacity with headstrong courage, obstinate determination, and a careless outspokenness.”3

Lucy grew up with a decidedly wealthy childhood. The family could and did travel often, and she got a great education. After finishing that formal education, she returned to Europe for a Grand Tour in the early 19-teens, but that was quickly scrapped as World War I broke out.

As an American citizen, Lucy could have easily fled to the US as soon as tensions in Europe spilled over into conflict in 1914. Instead, she stayed in Paris and worked as a nurse in a hospital, treating injured soldiers. The devastating injuries she saw there influenced her feelings of war in general, as we’ll see in a little while.

At some point, she met Selim Lawrence Schell, called Laury by his friends. He was the son of an American diplomat to Switzerland, and had lived most of his life in France as well. He studied to be an engineer but didn’t enjoy it. What he loved was cross-country car racing, but he didn’t have the money to participate, so he just watched and talked about it.4 He must have seemed directionless, because Lucy’s father tried to stop her from getting serious with him. Apparently, he said that Laury’s life seemed to, quote, “consist entirely of the pursuit of pleasure,” but, you know, nothing will get a strong-willed young woman to do something like telling her not to.5 Lucy continued seeing Laury and the two fell in love. Fortunately, they were a good match: Lucy had enough direction for both of them, and Laury’s engineering background and ease in going with the flow would come in handy during their car racing future.

But first, the bombing of Paris in April 1915. At that point, Lucy, her mother Henriette, Laury, and his brother all fled Paris for the US. We actually know that they probably applied for their passports to leave Paris together, because their numbers were issued concurrently.6 So clearly the intertwining of the families was already well underway by that point.

It’s unclear what they got up to between 1915 and 1917. But in 1917, Lucy and Laury returned to France to get married. World War I wasn’t yet over at that point, so it’s unclear what they were doing or even really where they were. Perhaps Lucy returned to work as a nurse in a hospital. We know that after the Armistice, they returned to Paris and lived the lavish lifestyle of the interwar period.

It was during this time that Lucy and Laury found themselves drawn to car racing. The automobile, first invented in the 1880s, had come a long way since early designs which were basically motorized carriages. Nothing spurs the development of transportation technology like war or competition, and the automobile industry had really benefited from an influx of government spending during World War I. But once peace had been negotiated, that technological growth could be turned toward consumer vehicles, and car racing as a sport really took off. Thanks to Lucy’s family money, she and Laury could afford to travel to races and eventually begin buying the latest and greatest cars for themselves.

In 1921, Lucy gave birth to her first son, Harry. Five years later she gave birth to Philippe. But if anyone thought that becoming a mother would get her to settle down, they were sorely mistaken. As Bascomb writes, “becoming a mother had the effect of revving her up.”7 She had begun enjoying car racing as a spectator, but she began racing herself sometime in the early to mid-1920s. One source credited this to Laury racing first in 1927, but I didn’t see more than one person claiming this.8 I’m not sure which of them was first to drive in a car race.

Lucy was not the first female race car driver, but they were few and far between. Just like Joe Carstairs motorboat racing in Europe in the 1920s, Lucy was often the only woman in a competition. Some races tried to keep women out entirely, but other tracks made female-only contests, thinking that it would be more fair for women to only race against other women. If that sounds unfair to you, I would agree but also point out that things like the WNBA and Women’s World Cup still exist to separate female athletes from male athletes.

And it’s worth noting–this was not behavior expected of a lady in the early twentieth century. In the US, women had won the right to vote, but in France that was not the case yet. France might have become a democracy and technically separated itself from the Catholic Church but it was a predominantly Catholic country and very socially conservative. The flapper, the icon of American female independence, was rare in France: Women still were expected to marry, keep house, have children, and–if they had money–act as “ladies of charity.”9 It was a strict model, and Lucy had to fight it basically every day she woke up.

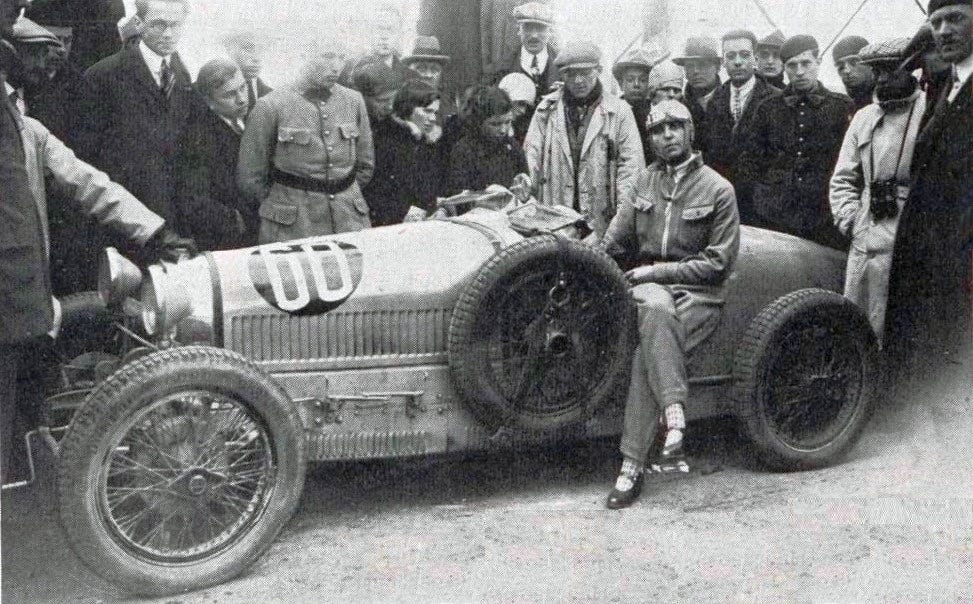

This was especially true in car racing, which is still today a male-dominated sport. There were other female drivers who had come before Lucy, but one of them, Camille du Gast, had found herself banned from events due to her quote “feminine excitability.”10 I’m kind of amazed women were allowed to compete alongside men at all–organizers spent a lot of time worrying about how the women would dress. I mean, what if their skirts blew up over their heads while they drove? (Tell me you don’t understand how skirts work without telling me, am I right?) In the end, women wore jumpsuits like the men did, but only while driving. Early female racecar drivers were rarely photographed in their jumpsuits; Lucy was expected to pose for pre-race photos in a skirt and heels then change before the race started. Men, of course, posed in their jumpsuits, not formal suits.

I don’t want to paint too rosy a picture here–women weren’t allowed to join factory teams, many races did forbid women from participating, and several rallies only allowed female drivers if they were co-drivers with a man. Lucy didn’t let all of this stop her.

Her first major outing as a racecar driver was at the Grand Prix de la Baule in 1927. She drove a Bugatti T37A, and was one of 17 competitors. A woman named Charlotte Versigny was also competing that day.11 14 competitors finished, and Lucy came in twelfth. Her entry into this race made her the first American woman to ever compete in a Grand Prix.

She competed at the Grand Prix de la Baule again the next year with the same Bugatti and finished eighth out of 14 finishers. The same year she drove at the Grand Prix de la Marne and finished sixth.

Lucy’s first major win was at the Coupe de Bourgogne voiturette race in 1928. Manufacturers used the term ‘voiturette’ to describe the smallest cars in their lineup, but voiturette races were races specifically for small cars, like three-wheelers and lighter cars weighing less than 800 pounds while empty. The top speed for these cars was usually around 45 km/hour or 30 mph, which seems slow today but was astonishingly fast back then.

She was clearly hooked on driving. She had the resources to drive the best cars outfitted to her specifications, as well as the grit to drive them in harrowing roads. She became known as a tough competitor, and not just “tough for a woman.” In fact, just before one race, she broke her arm in several places and her doctor told her to forfeit but she participated with her arm in a cast and nearly won.

In 1929, Lucy began following in the footsteps of other, quote, “groundbreaking speed queens like “The Godasse de Plomb,” Violette Morris, and “The Bugatti Queen,” Hellé Nice.” These women were particularly talented at the longer races; they set several long-distance speed records and participated in many endurance races. Lucy had already gained a huge reputation for being tough and a fierce competitor when she followed her female predecessors into long-distance endurance races. Her favorite race became the Monte Carlo Rally, “a challenge that, as one chronicler remarked, appealed to those ‘looking for trouble.’”

Rallies are endurance races in the extreme. Over several days, drivers start in various different cities and converge on one city, racing on surface streets all the way. The Monte Carlo Rally is, I believe, the oldest rally of this kind. It was first raced in 1911 and is still going on today. It wrapped on January 23, 2023, but you can watch the 2024 one in January. Competitors start from different cities then gather in Monaco–the ones that didn’t break down at least. What would be a pleasant and easy drive during the summer becomes a harrowing run through wintery conditions in the mountains as competitors try to make it back to Monaco in under four days. There are no service stations along the way, either. Competitors carry basic car maintenance tools in their cars with them and hope for the best. Many competitors drop out due to wrecks every year.

So this is Lucy’s favorite race and she attempted it numerous times. By the early 1930s, she was one of the most well-known and highest-ranking female drivers in Europe. In fact, in the 1932 race, Lucy and Laury were accompanied in their car by a reporter, Jacques Marsillac, who worked for Le Journal. The three began the race from Umeå, Sweden early on the morning of January 16. The road was covered with “a foot of ice, its surface glistening.” They shared the road with regular traffic, including not just cars but sleds and even families out on ice skates! Some accidents were guaranteed, and indeed the Schells in their Bugatti did drift into snow banks on more than one occasion when the tires lost their purchase on the ice.

The couple took turns driving, but both of them handled the car with, quote, “consummate skill.” They made it to their first checkpoint with 15 minutes to spare; they ate a quick sandwich and were back on the road. Conditions varied but never got better, and Marsillac was, quote, “particularly struck by how Lucy’s smile widened the tougher conditions became.”

They arrived in Monaco ninety-six sleepless hours later. Rain was pouring down, and they got out of the car, quote, “swaggering like conquering heroes.” They finished seventh, but it was still a heroic finish–only half the drivers who had started in Sweden had made it to Monte Carlo. Many had given up after accidents–or fear of accidents.

Marsillac chronicled all of this in a harrowing and exciting five-part series in Le Journal. Though Lucy was already well-known in racing circles and in the upper echelons of society where her wealth granted her entrance, his coverage made her a name most French people at least recognized. If you read French, I’m sure you can find it somewhere online. He concluded with “The dream has ended. Life must resume.” Little did he know how prescient that would be for France in the 1930s. The interwar period seemed like dreamy relief for a while, but a man named Hitler was rising to power in Germany at the same time, and real life would come crashing down around them.

But that wasn’t at the forefront of Lucy’s and Laury’s minds just yet. All this time, Lucy and Laury had been largely driving Bugattis in their races. They were good cars, but in 1933, Lucy was on the lookout for a new car. She found one in Delahaye. Even a year before partnering with Delahaye to build a race car would have been unthinkable. They were pretty but staid cars; French car historian François Jolly described their cars as, quote, “the perfect car to drive in a funeral procession.” It was a bad time to have this reputation: the worldwide economic crisis was putting several automobile companies out of business. France had “boasted over 350 manufacturers” but by the early thirties, only a few dozen remained. And the only manufacturers who had a reputation for fast and cool cars seemed to be surviving.

But in 1932, Madame Desmarais, widow of one of the original partners and still a majority shareholder, gave Charles Weiffenbach, the Delahaye production chief, marching orders to save the company. Her direction was, quote, “If you can’t build automobiles in quantity, build fewer but better ones. Win races to make the marque better known and to sell more luxurious and expensive cars.” It was good advice.

The next year, at the Paris Salon de l’Automobile, Weiffenbach and the Delahaye company debuted the Delahaye 134 and 138, small and sleek models. The 134 had a four-cylinder engine and the 138 and a six-cylinder. People went crazy over them, and orders streamed in, handily saving the company from immediate financial ruin. Lucy and Laury were there too, and after seeing the new cars, they strode straight into Wieffenbach’s office of Rue du Banquier. They ordered two custom 134s for the next Rally season, requesting that the larger 6-cylinder engine be placed in the lighter cars.

Little did Lucy know that this was actually already in Delayhaye’s plans. The idea had always been to field competitors in the races the next season, and car build was the most obvious way. But he didn’t want to give away the surprise, so he told Lucy it would be impossible, but that he could have a custom rally car prepared for her using the 134, called the 138 special.12

However, Weiffenbach not only failed to deliver this car in time for her to compete in her favorite Monte Carlo Rally in January 1934, but he had supplied that very car to his own factory driver, Albert Perrot. He had placed 24th out of 114, and Lucy felt sure she could have done better.13 Then Weiffenbach revealed worse news: two of Lucy’s rivals in the all-female Saint-Raphaël Rally would be receiving the 138 special before Lucy. The rage she felt at this probably inspired her to absolutely trounce the woman in her significantly less powerful Delahaye 134.14 She finished fourth place.

So Lucy did something a little sneaky and a little genius. She told all her rich friends to go to Weiffenbach and make the same request she had–the 138’s more powerful engine in the 134’s lighter body.15 Apparently, having several orders for the same car inspired them to work a little faster, as well as not cut Lucy out of the custom car she really wanted. The eventual result was the Delahaye 135, a great car for racing.

Now, at the exact same time, someone else in Europe was thinking hard about how racing could be used for fame and fortune. And unfortunately, that person was none other than Adolf Hitler. On February 11, 1933, just twelve days since taking leadership of Germany, Hitler opened the Berlin Motor Show. There, he vowed to, quote, “slash the taxes and regulations that were suppressing the motor industry, to align its growth and development with aviation, to build a nationwide highway system, and to dominate international motorsport.”16

Germany was experiencing a financial crisis on another level from what the rest of the world was dealing with at the time. Everyone was suffering, but Germany’s economic woes after World War I had bankrupted the country. And it was on a platform largely about economic recovery that Hitler was elected to office. So this claim was par for the course with him.

However, manufacturers like Mercedes Daimler-Benz also knew that Hitler wasn’t stopping at flashy cars. This was part of a larger plan to reinvigorate the German military, contrary to promises signed in the Versailles Treaty at the end of WWI. Car racing was truly just the first step. As Bascomb writes, quote, “wins on the international stage would provide a marketing bonanza, particularly when it came to growing the export market.”17 To support this car racing marketing mission, the Reich split 1 million German marks between Daimler-Benz and Auto Union, a conglomerate of four car companies including Audi. They were given their orders to create winning race cars that could make Germany look good.

Lucy watched this development with anxiety, exacerbated by France’s seeming inability to have a government or contend with its own Fascist forces. The French government was “in shambles, with prime ministers and their cabinets rising and falling in months,” as opposed to years.18 Memories of World War I fresh in her head, Lucy worried that Hitler’s growing strength and France’s weakness meant the two countries were on a collision course.

In 1934, Lucy finally raced a Delahaye at the Paris-Nice Rally. The race took 6 days, from March 24th to March 30th. She finished 8th, the top woman and top American in the race. The cars ahead of her were a Hotchkiss, a Panhard, a Ford, a Bugatti, another Panhard, and another Hotchkiss. It was a great showing, and she won the Coupe des Dames for it. The next day, at the Automobile Club de Nice, she was celebrated for her, quote, “admirable virtuosity” in the race.19

Also celebrated that day was a driver named René Dreyfus. He had entered a smaller race that was part of the rally, and won it in a Bugatti. The two had never met before that day, but were familiar with the other’s reputation. René probably knew Lucy’s sons more–they were always hanging around racetracks, even when Lucy wasn’t racing. They chatted and became friends that day, not aware that they were forming a partnership that would go down in history.

René was a very talented driver who had only been racing for a little while at this point. Born in 1905, he was almost ten years younger than Lucy but he had shown such promise at the Monaco Grand Prix in 1930 that he was kind of revered among French drivers. René was born and raised in Nice, in a culturally Jewish community and family, though his family wasn’t particularly devout. He apparently never had a bar mitzvah and rarely attended temple, and in fact preferred his Catholic mother’s religious leanings.20 But because he shared a last name with France’s most recent famous political scandal, everyone guessed his Jewish heritage.

Real quick: The Dreyfus Affair was a political scandal that divided the Third French Republic and had only cleared up in 1906, after René was born. It involved a Jewish artillery captain in the French military, Alfred Dreyfus, who was falsely convicted of passing military secrets to the Germans in 1894. It was a clear case of anti-Semitism, made obvious by the way that crowds shouted, quote, “Death to Judas, death to the Jew” when he was publicly stripped of his military uniform.21 It’s awful. Author Emile Zola famously defended Dreyfus in his open letter titled “J’Accuse…!” Which, even if you’re unfamiliar with this story, you’ve probably heard that joke in sitcoms–it’s used a lot in New Girl. In “J’Accuse,” Zola was accusing the French military of covering up the real leak–who we all later found out was a Catholic French officer with German heritage, Charles Walsin Esterhazy. Zola was convicted of libel for his troubles. Eventually, the truth came out and both Dreyfus and Zola were pardoned; Dreyfus was able to return to France and was reinstated to the military.

But despite nearly 30 years passing, no one in France had forgotten about the Dreyfus fiasco and as anti-Semitic rhetoric was ramping up in Germany in the 1930s, René found himself the target of overt and obvious prejudice for the first time. Obviously, France was no stranger to anti-Semitism and René was watching these developments with some trepidation. But then, in 1934, he had no way of knowing that he would quickly be out of a career because of his heritage.

In late June and early July 1934, the new German race cars funded by Hitler made their first appearance outside of Germany at the French Grand Prix at Montlhéry. The cars stunned witnesses. They were silver-bodied and had a “strange silhouette”--low and sleek, with a pointed nose.22 Not only did they look like predecessors to jets today, but they moved at a speed few humans had ever witnessed anything move at; it must have been equal parts scary and exciting to see these machines that seemed like they’d come back in time. At the race, they clocked an average speed of 90 mph, or 145 km/hour–the fastest race cars up to that time could maybe clock 120 km/hour on a long straight run, but the German cars could hug the ground and keep that speed up even when making frequent turns. They earned the nickname “The Silver Arrow” because of their looks and how fast they moved. However, though they were fast, the cars weren’t up to the endurance part of the race, and all the Mercedes Silver Arrows were eventually forced to drop out.

The German announcers and team managers were embarrassed–they’d been cocky before the race–but for Hitler’s purposes, the cars were also already doing their jobs as marketing ploys.23 While people were enthralled by the appearance of the Silver Bullet, newspapers were trying to report the sketchy details of some sort of “Bloody Day of Repression” in Munich and Berlin.24 No one was quite sure what had happened, but people were trying to report that something had. Later, this weekend would go down in history as the Night of the Long Knives, when Hitler ordered the assassinations of several rivals in the Nazi party and out of it. Still today the full death toll is unknown; we know of 85 people for sure, but some estimates run to over 700 people who were murdered over three days in Germany. Hitler was cleaning house, and pulling his fancy new cars out of the garage for the first time was the perfect distraction.

To be clear, it seems like the automakers and drivers were equally as in the dark about the assassinations as everyone else. They were being used, though they probably knew more as soon as they returned to Germany. More importantly, thee German cars became famous, and their drivers became overnight celebrities. That celebrity was the perfect pro-German propaganda tool, so Hitler poured even more money into these programs, ensuring German race car dominance. Soon enough, the German national automobile club was head to say that the power of the Silver Arrows was, quote, “the benchmark for the industrial ability of a whole people.”25

Which might seem crazy to say, considering that none of the Silver Arrows finished this race! But anyone who had seen the race knew that despite the fact that not a single Mercedes finished, this wasn’t a bad showing for Mercedes. It was their first race with a wildly new car model; once the kinks were worked out, they’d be unstoppable. Every automaker went home after that weekend nervous. Moreover, the race was, quote, “a national embarrassment” for France, because not a single French-manufactured car finished either.26

At this time, René was driving for Bugatti, the only French car brand that had entered the Monthléry Grand Prix. He saw the power of the Silver Arrows and became frustrated by Bugatti’s slow pace of development. He was hampered by how they were falling behind technologically, but the press hounded René directly for not driving France to victory.27

He alone went to the Swiss Grand Prix in Berne, determined to race against the Silver Arrows and place well for his own reputation and Bugatti’s. He noticed that the pre-race atmosphere had changed–before 1930, drivers had comingled, their association as drivers more important than their nationality or team. But in Switzerland, René saw that everyone stuck to their national teams, refusing to intermingle. It was a bad sign.

When he finished third behind two German cars, a fight broke out in the stands between German fans and French fans. The experience, quote, “left him depressed. His sport had become lost in the widening chasm between countries.”28 Races had stopped being competitions between drivers and teams; they were just another arena for a tense international political situation.

After Switzerland, René left Bugatti. When they parted, his team manager, Constantini, quote, “urged René to find something to struggle and fight for. Until that moment, greatness [as a driver] would elude him.”29 René had been facing criticism for being too cautious after a terrible accident a few years before, and he knew that Constantini was probably right. Little did they know, he would find something to fight for soon enough.

René was leaving Bugatti because he’d been offered a place on Ferrari’s team for the 1935 season. It was a better team and a better car, but it didn’t matter–the Silver Arrows fulfilled their promise of figuring out the endurance portion of the race. Soon the podiums at every race in Europe and North Africa were filled by German competitors finishing one-two-three, though René managed to finish second at Monaco. At the Belgian Grand Prix, René spent so much time just short of passing the Silver Arrows that he grew sick from their poisonous exhaust fumes and had to quit the race early. He compared the fuel to chloroform, and his eyes and mouth were so irritated by whatever they were using in their fuel that he had to bathe his face in milk to soothe his skin.30

Around the same time, during the 1935 season, Lucy’s Delahaye 135 had undergone a series of improvements. She’d been placing well in all the races she entered, including placing third at the 1935 Monte Carlo Rally.31 Though she was focused on her own endurance races, she was also watching closely to what was happening on the Grand Prix circuit. She was also starting to think about the next stage of her career–nearly 40-years-old by that point, racing probably wasn’t as comfortable as it used to be. These multi-day rallies required drivers to barely sleep or eat for days at a time, and that wears a person out. I’m 32 and I can’t imagine doing it, I’m sure that at 38 Lucy was starting to think that maybe she wasn’t going to do it for much longer.

She began putting together the framework of a racing team. She had the money from her family wealth to finance whatever initial seed money she’d need. And more importantly, after a few years of working together, she really felt like she’d found a partner in Weiffenbach, someone she could depend on to reliably supply her with the right cars. Plus, plenty of other drivers had formed their own teams; why not her?

At the same time that Lucy was starting to think about getting her own team formed in time for the 1936 season, René was realizing that it had been a mistake to move to Ferrari. Nationalism had so infected the racing world that even when he was poised to win races, Italian fans didn’t want to see a French Jew win for them. On at least one occasion, at the Italian Grand Prix, René was poised to win only to be asked to relinquish his car (and therefore his place in the race) to his Italian teammate, Tazio Nuvolari so that an Italian could win in an Italian car at an Italian race.32 Nuvolari came in second. They were teammates, so René was probably polite about the whole thing, but I think we can all imagine how frustrated he must have felt. Had he been driving, Ferrari could have won, a victory for Italy! But they would rather have second place with an Italian Catholic? It must have been hard to stomach.

And then came the blow: Mussolini demanded an all-Italian team for the 1936 season.33 René was out. He and his wife Chou-Chou moved back to Paris. Without the money he would need to race as an independent, René was momentarily adrift. But he was soon recruited to be the team leader for Talbot who was creating a team to compete in sports-car races.34

Though the title was flashy, the reality was that René was there to babysit a young driver named Jimmy Bradley, whose dad edited the famous magazine Autocar.35 Jimmy was, realistically, a mediocre driver. Worse than that, the Talbot car was plagued with mechanical troubles, and soon after René signed with them he probably realized that 1936 was not going to be a winning season for him. More importantly, he missed the Grand Prix circuit.

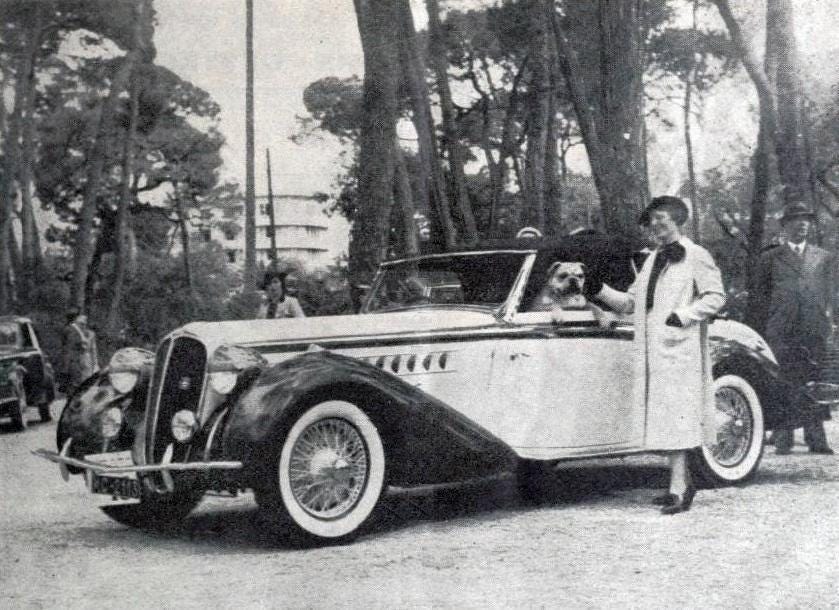

Around the same time, Lucy was ready to launch her new team, all driving Delahayes. She called it Blue Buzz and she and Laury both were members. She also recruited Germaine Rouault, a 28-year-old French female driver and veteran French driver Joseph Paul. Germaine Rouault is an especially fun driver that maybe I’ll revisit someday–she arrived at races in a leopard skin coat with her dog in tow.

In January 1936, Lucy was competing once again in the Monte Carlo Rally. She and Laury had 2,400 miles to drive from Athens through Hungary and Austria before hopefully arriving in Monte Carlo in her Delahaye 135. The weather was warm, which boded well for their ability to finish. Though they hit bad weather in Vienna and Salzburg, they still entered Monte Carlo on schedule. The next part of the rally was a performance test, featuring a test that involved turning a figure eight around two pylons at high speeds. The Schells posted a time of one minute, 5.4 seconds for the test, blowing away the competition that had come before them.36 Lucy could practically taste it: Winning the Monte Carlo Rally might finally happen.

But then Romanian driver Petre Cristea, in his Ford V8, beat their time by about half a second.37 He won the 1936 Monte Carlo Rally and the Schells settled for second. But Lucy was devastated by this; she was almost forty, and she had a feeling that her chance of being the first woman to win the Monte Carlo Rally was basically over.

The next month, Lucy performed poorly at the Paris–Saint-Raphaël all-female race. Her only consolation was that Germaine Rouault won, securing Blue Buzz their first team win. Then at the Paris-Nice Rally, Lucy suffered a series of bad days of driving. The actual racing between cities was fine, but she was struggling with the performance tests. Rouault, who was also competing for Blue Buzz in the rally, was performing well, and Lucy’s competitive streak with her own teammate almost got her killed; Lucy took a turn on the course way too fast and almost launched her car off a cliff; she finished thirty-third out of thirty-four.38 That Laury won in the end, securing another win for Blue Buzz, probably cheered her up, but not much.

In addition to these losses, two other events in early 1936 convinced Lucy that it was time to stop driving to focus on managing her team. The first was the new Grand Prix formula for 1937 to 1939. Charles Faroux, a long-time commentator on French motorsport had lamented that the new formula, which established a sliding scale of weight-to-engine ratios, would let the German teams, with their unlimited funds from the Reich, win handily.39 He also complained that the French government was not matching the pace of investment that other countries were putting into their cars, leading to further French racing weakness. Lucy heard this and agreed.

The second event to convince Lucy to focus on managing her team was Hitler’s invasion of the Rhineland. It was clearly an act of war but the French government, weak and financially strapped, did nothing about it. Lucy could see how the indomitable Silver Arrows were the front line of a drumbeat of Nazi propaganda about their supposed natural dominance in all realms of human activity. She had not forgotten her work in the war hospitals of World War One.

Until this moment, Blue Buzz had focused on rallies and sports car races, but she decided she was going to use her young team to win a Grand Prix. Her goal? Show the Nazis that their days of unrivaled dominance were over. Plus, she may never be the first woman to win the Monte Carlo Rally, but she could be the first woman to own and manage a team at a Grand Prix, which was good too.

She went to Weiffenbach and told him her plans. He may have had some doubts as she laid out her plans. Lucy had raced in a Grand Prix but not for a while, and this shift in focus was a far cry from what other car manufacturers in France were doing at the time. Only Bugatti was still fielding Grand Prix cars. And it’s worth noting–Grand Prix cars were significantly different from the regular sports cars Delahaye had been racing. The point of Delahaye getting back into the racing world had been to show off cars that spectators could imagine actually owning and driving. But Grand Prix cars, much like Grand Prix cars today, were not built for regular roads. They were, quote, “too powerful and temperamental for the typical driver to handle.”40 They were expensive to design and even more expensive to maintain, and the brands that did it were backed up by, quote, “legions of engineers, vast sums of money, and clear government support against which Delahaye was Lilliputian.”41

But then again, Weiffenbach knew Lucy well by this point. And since she promised to finance it all herself, it could only make Delahaye look good. If the car failed, they wouldn’t lose money, but if they won it would be a windfall of investment from fans and car buyers.

If the money wasn’t enough to convince him though, patriotism was. Lucy was rechristening her team for the Grand Prix races. She transitioned from the cutesy “Blue Buzz” to “Écurie Bleue,” French for Team Blue, a reference to the color that had traditionally represented France for centuries. Weiffenbach was in.

Still, he was pragmatic in the approach. He decided that any design Delahaye pursued had to serve as a basis for a real car the general public could buy, which meant that there wasn’t a supercharged engine in their future. Instead, they made a 4.5 liter V12 engine, which could also be dropped into a consumer sports car.42 They began calling the car the Delahaye 145.

Designing and building the car was delayed by widespread labor strikes across France in 1936. But they felt sure that they could have four 145s ready for testing by early 1937. Lucy began her search for Écurie Bleue’s first Grand Prix driver. Though her husband Laury and their other driver, Joseph Paul, had done well at the French Grand Prix, they needed a driver who had been through the testing phase of a new Grand Prix car, who could give input on design.

Lucy also thought they needed someone desperate–they were never going to be able to poach a worthy driver from a team like Ferrari. Even if someone like Nuvolari was a) allowed to leave the Italian team (Mussolini never would have let him) and b) could stomach taking orders from a woman, someone that established would never take the risk of joining an untested independent team. So Lucy needed someone desperate to prove himself.

I don’t know why I’m building up the suspense, you all know where this is going: There was only one driver that fit the bill. René Dreyfus. She knew he was a driver with, quote, “finesse and intelligence” plus, quote, “great precision who could teach a class on holding a line.”43 Plus, he had a reputation of being calm and, quote, “patient as an angel.”44 He was the perfect candidate for a fledgling team testing a car to field against Germany.

When the two met, Lucy knew she had to blow him away. Though he was ten years younger than her, he was not a young new driver, he was experienced. By then he had driven for Bugatti, Alfa Romeo, and Maserati; he was not going to be easily impressed. What she wasn’t sure of was his estimation of her. Luckily, René was impressed by her and what she had achieved so far with Delahaye. He also knew of her wealth and that the team would have anything they needed to succeed. He would have, quote, “a salary, his pick of other drivers, and the freedom to help develop and test-drive the new car.”45 Together, they could put René on top and stick it to the Germans, which was something they could both be proud of.

What I love is that, together, they could be outsiders who won. She, a woman in a male-dominated sport, he, the only Jewish man in the Grand Prix–it had to be a very tempting image.

So René signed on to Écurie Bleue and test driving began. He had his flares of doubts–Delahaye was building a Grand Prix car from scratch and Lucy had no experience on the Grand Prix circuit. But the gamble was worth it. And René liked Lucy’s, quote, “brashness and unswerving passion.”46 On December 10, 1936, Lucy and Weiffenbach announced to the press the formation of Écurie Bleue with Delahaye cars and René as their lead driver. They initially planned to first race in the 1938 season, giving them a year of testing.

And then three weeks later, the French government announced The Million Franc Prize. On December 31, 1936, the French government was finally going to do what the Reich had been doing for years: They were going to put money into French automobile makers who were building a car for the Grand Prix. It was explicitly to raise France’s profile.

The money was actually about 1.5 million francs, but “The Million Franc Prize” sounded better. The government set up two contests. The first had a deadline of March 31, 1937, just three months later. Whichever car completed the fastest sixteen laps at the Montlhéry road circuit would win 400,000 francs. The car had to meet a minimum average speed of 91 mph, or 146.5 kph, which was easily done. The car also had to meet a formula standard and engine limit, but the deadline was far too soon for manufacturers to design a whole new engine for the race. Conveniently, Bugatti already had a car that met the formula standard and engine limit; clearly the scales were tipped in their favor; it was basically designed to be a grant to Bugatti without actually being one.

So everyone else turned their attention to the second contest, which had a deadline of August 31, 1937, and the victor there would win the 1 million francs. The prize would go to the car that completed the fastest sixteen laps at the Montlhéry road circuit, but this time without the formula standard or engine limit. Obviously, Delahaye would enter, alongside most other French car manufacturers. One French historian wrote, quote,

It was to catch the imagination of the French public as no other motor racing event has succeeded in doing, either before or since: a drama on a national scale playing on some of the deepest human instincts and emotions–passion for sport, admiration of skill and prowess, love of country–and all that brought to the boil in a cauldron fired by that most magical of all motivators, lust for money.47

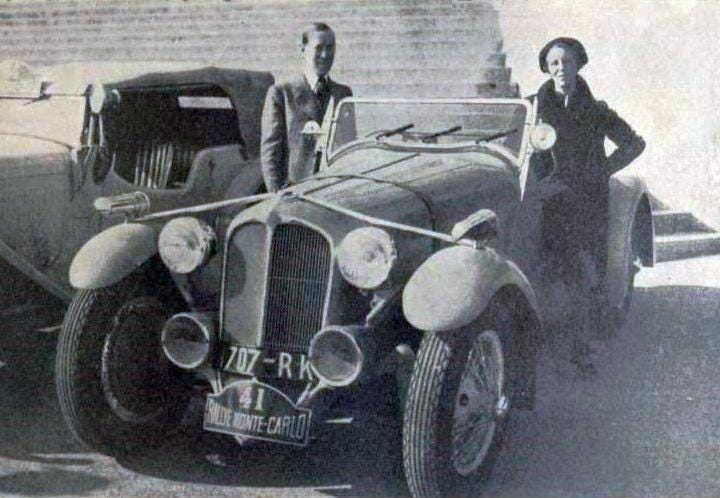

While Lucy and Weiffenbach prepared for the Million Franc Prize, she sent Laury and René to compete in the Monte Carlo Rally in January 1937. René had never competed in a rally, but he thought that the 25 mph average speed would feel almost peaceful after the high-octane speeds of a Grand Prix. Plus, he and Laury were quickly becoming fast friends and competing together could only cement that. René was of course wrong about his peaceful predictions–he and Laury chose Stavanger as their starting point on the way to Monte Carlo that year and the weather was awful. They drove through one of the worst winter storms in decades. René had never raced on ice before, but he got plenty of practice, getting to know the Delahaye car very well in the process. Together they finished fifth overall.

All that spring, they worked on the car design, racing to get it ready for the August 31 deadline. They worked and worked, finally creating a light magnesium V12 engine that weighed about half of what a standard iron engine that size would have weighed but provided 50 percent more power and turned 1,000 rpm faster.48 And if you don’t speak car (I don’t)--it was a better, much stronger, faster engine. The fact that they did it in just a few months speaks to how good their designer, Jean François, was.

Meanwhile, René kept racing all spring, representing Écurie Bleue in the 135s Lucy had raced. But all season long they were, quote, “bedeviled by accidents and mechnical failures, leaving Bugatti and Talbot to dominate the French sports-car races.”49 But true to his reputation, René was unfailingly tenacious and positive about their prospects.

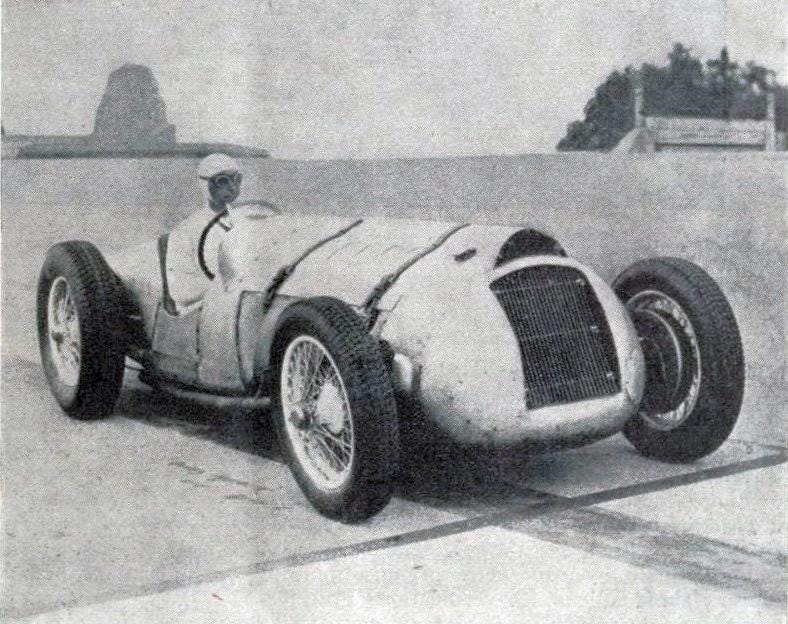

On June 25th, the Delahaye 145 arrived at Montlhéry for testing for the first time. Lucy, careful this time, called no press for the event. The witnesses there were shocked–the 145 looked nothing like its predecessors. One person described the car this way, quote,

Gone was the classic shield-shaped radiator surround… In its place was a broad blunt snout… Gone, too, was the slim tapering profile of the old ‘Six’; the V12 body maintained the same ample girth all the way from the front to the back of the cockpit, its sides thereafter drawing in only slightly toward the flattened tail. The car seemed to hug the ground, its extraordinary low build making it look even longer and wider than it was.50

Other observers were more opinionated, calling it “weird,” “brutal” and one memorable person saying it was “downright ugly.”51 Even René thought it was, quote, “the most awful-looking car [he] ever saw.”52

But that opinion disappeared as soon as he saw it in action. Designer Jean François tested it first, since he’d designed it and knew it best. As René watched he said, “She’s pretty, is she not? She rides low and gives a beautiful impression of power.”53 Once François was sure the car wouldn’t blow up, he let René do the real test drive. After a slow lap to get a feel for it, René sped up to 126 mph and began putting its car through its paces. Most worryingly, after half an hour the engine overheated. Even at 126 mph, the sixteen laps necessary to win the one million would take longer than 30 minutes. The car wasn’t ready.

The designers kept working on it. Just over a week later, the car returned to Montlhéry for the French Grand Prix: The 145’s first race. Observers didn’t know what to make of it. Autocar wrote that the 145 looked like a “winged beetle.”54 No one knew how it was going to perform; there were still unresolved problems, and they made themselves known by the second lap. A cylinder was misfiring, then 24 spark plugs needed to be replaced. Suddenly the oil pressure dropped and the car went from purring to limping. By the seventh lap, René knew he had to abandon the race.

A few weeks later, René raced in the 145 again at the Grand Prix de la Marne. The engine was doing better but that time a tire blew, causing the car to spin dangerously off the track. René was furious and Lucy not much better, but they both knew that the races were really just another form of testing for the Million Franc Prize on their way to defeating the German Silver Arrows in 1938.

Starting in late July, Lucy insisted that the Écurie Blue team all but move into the Montlhéry race track. There was just over a month until the deadline for the prize and they needed to devote every second to it. First they began reducing the 145 to its essentials, even taking out the second seat to help reduce weight and make it easier for the car to meet the average speed limit. Soon, reporters began camping out as well, speculating as to who might take the prize. Bugatti had won the first 400,000 francs, but they hadn’t even done it easily, despite the test being designed for them. So that summer it seemed like it could still be anyone’s game.

René knew that he would need to average five minutes and seven seconds per lap to have a shot at winning. The car had to be at a standing start, too, so he would certainly lose time on the first lap while the car got up to speed, meaning that he would need to go much faster than the five-minute seven-second average for several laps to make up for it. Moreover, that was just the minimum speed they had to go; the prize would go to whoever did it the fastest, not the first one to achieve the sixteen laps at the minimum speed.

The second half of August was tense. Bugatti planned to make their attempt on August 14th with their champion driver, Jean-Pierre Wimille. But then Wimille was in a terrible car accident on his way from Provence to Paris for the attempt. He would recover, but whether he could by August 31 was unknown. He had internal injuries and a concussion that left him with severe headaches for weeks.

On August 18, René was feeling that the 145 was ready to make the attempt, only for the gearbox to suddenly break. It would take several days for them to fix it.

Jean Bugatti was getting nervous as the days in August dwindled down. He put an older driver, Robert Benoist, in the car they had prepared for the prize. The 42-year-old was skilled and had one several Grand Prixs in the past, but he didn’t make the cut. His fastest times were too slow to meet the minimum average speed requirements. After the attempt failed, Benoist admitted that Wimille could have done it faster and fervently hoped he would recover in time to make the attempt.55

In the papers, reporters publicly wondered where the other French manufacturers were. Talbot had promised to field a car but had yet to show up. It seemed like it was down to Bugatti and Delahaye, and people were beginning to wonder if the goal was even possible. The public was obsessed with this, by the way. Not only was it an exciting challenge–high speeds, a million francs–but it was also a welcome distraction from the loud drumbeat of war coming from their neighbor, Germany.

On Thursday, August 26th, Lucy, Weiffenbach, and Jean François felt ready to make the attempt again. The gearbox had been fixed, and the mechanics had further decreased the car's weight by hollowing out anything that wouldn’t impact the car’s structural integrity.56 They even punched holes in the pedals to make them more aerodynamic.57 Only René remained unsure if the car was ready. And I suspect it was less about the car and more about him–car racing is so often a driver against opponents. But this race would be René and the 145 alone on the track, racing the clock. Mentally, it was a very different challenge.

There were genuine issues with the car too, René claimed. Weiffenbach disagreed, and late that night, after René went home, Lucy and Weiffenbach called René’s wife, Chou-Chou. They chatted for several minutes, but she assured René it was nothing. The couple went to bed.

Then at 5:30 am on the 27th, Chou-Chou woke him to inform him that it was time; he’d be trying for the One Million that day. He tried to back out, but she told him it was too late; the official timekeepers were on their way to the track and the press had been informed. Soon all of France would know he’d tried that morning.

Clearly, she and Weiffenbach and probably Lucy had all seen that René was procrastinating. Nervous. It was a lot of pressure! So they forced his hand.

René was angry at this backstabbing double-cross. He was even angrier when he began to suspect that the team had deliberately made him mad to make him more aggressive during the run. He was even more furious when he realized how easily he’d been played. But he couldn’t disappoint everyone by simply refusing to show up, so he went.

When he arrived, the engine was already warm and everyone was already there. He changed into his white racing suit but refused to greet Lucy or Weiffenbach. He got in the car and warmed up. Finally, after a short break, he pulled up to the starting line and began his attempt for the Million Franc Prize. He knew the math by heart by then: He had to do sixteen laps in one hour, twenty-one minutes, and fifty-four seconds or less.58

In addition to the Ecurie Bleue team, Delahaye engineers, and the press, the stands were also home to Robert Benoist, from Bugatti, and Prince Wilhelm von Urach, a manager for the Mercedes race team. Both wanted to size up the competition.

At ten in the morning, the flag dropped and René leapt forward in the Delahaye 145, beginning the biggest race of the team’s short life.

The first lap clocked at five minutes, 22.9 seconds. That was 16 seconds slower than he needed to be on average, meaning he was deeply in debt. They had all known the first lap would be the slowest, but René had hoped to post a better time than that.

His second lap was faster, but still not fast enough. The third lap was perfectly on time, which was probably a huge relief to Lucy where she was watching from the stands. But that didn’t make up for the deficit of the first two laps, and René struggled to go any faster until the seventh lap. Worse, the wind was beginning to pick up, and he had to fight it at every turn.

Finally he got his lap average down to five minutes five seconds, meaning he was chiseling off the debt of his first two laps every time. The wind hadn’t abated though, and René also knew he was pushing the limits of what his Dunlop tires were capable of. In fact, a rep from the tire company was on the course to alert him if he saw any sign a tire might blow–at the speeds he was going, in that autodrome, René would be lucky to survive a blown tire.

In the thirteenth lap, an unexpected wrench was thrown in: A farmer nearby was burning weeds. The smoke billowed onto the track, obscuring the road. A less experienced driver might have stopped immediately–it was dangerous to drive at that speed without visibility. But Lucy had pushed René to drive the course multiple times a day, until he knew it, quote, “like his own bedroom in the dark.”59 He took the turn “on faith” and finished the lap in five minutes, 5.3 seconds.60

The fourteenth lap was his fastest yet: five minutes, 3.9 seconds. He’d had his doubts, but everyone in the stands felt sure that the million was within reach, assuming the engine held.

But then on the fifteenth lap, the Dunlop man began frantically waving his arms. He was warning the Delahaye team–René needed to stop. The tread on one of the tired was wearing off and could blow at any second. But René continued; he was finally done being cautious. He kept going, and Lucy didn’t order him to stop. When René passed the Dunlop man again on the sixteenth and final lap, the man was praying, making a sign of the cross. René didn’t let it scare him but finished the challenge, quote, “like a man possessed.”61

He’d done it. Despite starting deep in the hole, he’d come in 4.9 seconds under the limit. He’d qualified. If no one beat his time in the next four days, the Million Franc prize was theirs.

When he finally slowed on the track, a crowd had already gathered. They were cheering and jumping around, relieved and overjoyed at his success. When René realized what he’d done, he wept in joy and relief. Not only had he made this challenge, but he also had redeemed his own reputation after years of bad luck. He stepped away, but Lucy joined him and the two cried together.

The whole team and a gaggle of journalists went to the restaurant attached to the autodrome to celebrate. René was quoted in the papers the next day as saying, quote, “To win the prize, it is necessary to take great risks.”62 Rumor had it that Wimille was recovered enough from his injuries to try for the prize the very next day, but the team didn’t let that dampen their excitement. If nothing else, they had made it that much harder for Bugatti to win; now they needed to be René’s time.

On Saturday, August 28, Wimille took a test drive around the autodrome. His head was still bandaged, but he didn’t hesitate before getting into the car. They announced they would be ready to make their attempt on the 29th.

But that day, no one showed. Écurie Bleue waited, ready to go in case Bugatti beat their time and René needed to make the attempt again. Late that night, Jean Bugatti announced that Wimille would try the next day, Monday August 30.

But it was the same story. No one ever appeared. Écurie Bleue returned to the track on Tuesday, August 31, waiting to see what Bugatti would do. Lucy and René were both wrecks, wearing the same clothes they’d been wearing for five straight days for good luck. René drove the car around the autodrome a few laps, just to have something to do. He and Lucy fretted, and she was struck by the terrifying possibility of a strategic gambit: What if Bugatti planned to make their attempt at 6 in the evening, finishing the race at 7:15 pm? It would be too late for René to make another attempt then because it would be too dark on parts of the track. Race cars don’t have headlights and the kind of overhead lighting that would make a night attempt possible wasn’t installed at Montlhéry.

She hurried to petition the Million Franc committee members for a last-minute rule clarification. If Bugatti showed up and tried this, could the 145 start 2 minutes after Wimille began, ensuring that the two cars would never run into each other on the track.63 The committee decided they could, sparking a last-minute excitement that the competition for the million would in fact be a proper race after all. Somehow, news of this decision got out, and suddenly enthusiasts started pouring into the track.

Sure enough, at 4 pm the Bugatti team finally arrived. They began their attempt, but something immediately went wrong. Minutes ticked by, long after Wimille’s first lap should have been completed. Finally, the car limped back to the starting line and news trickled up into the stands: The rear axle was broken.64 The Bugatti mechanics fixed it, and at 6:43 pm, Bugatti began their attempt again.

René, thanks to Lucy’s last-minute rule clarification, was ready on the track. Two minutes later, he took off. On his second lap, René spotted the Bugatti car motionless on the track; it had had another mechanical issue. He kept going, making better time than he had on his first attempt. Bugatti got back on the track as René was finishing his fourth lap, but quickly pulled back out; this time the engine was leaking oil. That was it; they were finished. The Million Franc Prize belonged to Écurie Bleue.

His team stopped him after his sixth lap. He’d been making great time, but there was no need for him to risk it. Wimille congratulated René on his driving, and the team went out to celebrate.

The press lauded René and the Delahaye car in the press. Both Weiffenbach and René made sincere attempts to acknowledge Lucy’s role in creating and funding the team, as well as helping design the car, but almost no newspapers mentioned her at all.

It must have stung, but Lucy swallowed her hurt because she was only getting started. Part of the prize was used to fund car improvements in order to beat the Germans in the 1938 racing season.

René and Lucy both geared up for the Grand Prix season. The 145 was in great condition. And Hitler’s aggressive moves on the world stage were inspiring the Écurie Bleue team to drive well against the German cars. In March, he annexed Austria, encouraging violence in Vienna that escalated into a pogrom. No one–not France, nor Britain, nor the UK–did anything about it. Lucy was surely livid.

The Pau Grand Prix in France was the opening race of the Grand Prix season. Rather than have René prepare or rest, Lucy sent him to race in the Mille Miglia in Italy. René knew it was the right choice; it gave him less time to brood about everything that could happen at Pau. René and his co-driver, Maurice Varet, placed fourth despite suffering from a punctured radiator. When René left for Pau, Lucy didn’t accompany him, deciding to compete in the Concours d’Élegance happening in Cannes at the same time. But she gave him some parting advice, reminding him of the importance of a French win over German drivers. As Bascomb wrote, quote, “A single victor over the Silver Arrows at Pau might not change the tides of nations, but it could spark hope in a world darkening at every turn.”65 René left for Pau aware of the weight of import on this race: This wasn’t just about winning, it was about challenging German claims of racial superiority.

Écurie Bleue arrived in Pau, where the drivers helped the mechanics unload the 145s. Their all-hands-on-deck shoestring operations was a stark contrast to Mercedes, who arrived that date, quote, “like an invading army…one of [their trucks] was fitted out as a mobile workshop.”66

Sixteen competitors would race at Pau. Two for Écurie Bleue, their cars now painted blue with stripes of red and white that resembled a V for Victory when viewed from above. Every other major race car manufacturer in Europe was in attendance, making the race all the more exciting. It would be a grueling 100-lap race with a 30,000-franc prize.

First came the timed trials, which would determine each driver’s starting position for the actual race. René finished second there, earning him a beneficial start. Several other drivers did not fare so well; Talbot dropped out entirely, and Bugatti had never even shown up. That night, Lucy visited a fortune-teller in Nice, unwilling to wait until after the race to know who won. The fortune-teller told Lucy that one of her “mechanical horses” would win the next day.67 She called Laury to let him know the good news.

It’s worth noting that Lucy was rather famous at this point, and the fortune-teller might have known her on sight. There’s a chance that she just told her what she wanted to hear.

Meanwhile, in Germany, Wilhelm Kissel, chief executive of Mercedes, needed a Mercedes win. In a speech, he said, quote, “Victory in the Grand Prix was not only a victory of the driver and builder in question, but always at the same time one of the whole nation.”68 Clearly, a defeat for Mercedes would be a humiliating defeat for Germany.

When the morning of the race dawned, René followed his pre-race ritual. He took off his wedding ring and watch, triple-knotted his shoelaces, then clipped off the ends to prevent snags on the pedals. He arrived at the course soon after, ready and relaxed for the 2 pm start.

More drivers had dropped out overnight, leaving the field winnowed down to only eight drivers. For all intents and purposes, it was Delahaye versus Mercedes. And, as an extension of that: France versus Germany.

When the race began, German driver Rudi Caracciola leapt away from the starting line, easily taking the lead. René kept on him tightly, following the plan he’d laid out with his team: stick close to Mercedes for second place, then pass when they inevitably needed to refuel. For all that Mercedes was fast, they hadn’t solved their gas consumption problem. In the 100-lap race, they would need to refuel at least once, while René might not need to at all.

Unbeknownst to many, Caracciola was struggling on the track. The course was full of tight corners through the streets of Pau; the average speed of the cars was only 55.8 mph. The engine in the Mercedes was just too powerful for that low speed, and he struggled to control it.

In the seventh lap, René passed Caracciola on a downhill curve. He kept it, blissfully free of the noxious gas the German car put out, but now the two cars faced a different problem. They were much faster than everyone else on the track. The city street’s sharp turns not only meant that the drivers had to slow down, but it also meant that they were often turning blind and coming up on their much slower competitors.69

Caracciola eventually passed René, but that was okay. As long as René didn’t face mechanical troubles, he could still overtake the German car when it stopped to refuel. From Cannes, Lucy listened to the commentators on the radio with bated breath.

As the race continued, the track became slick with oil and rubber from the other cars. Caracciola struggled even more to control his powerful Mercedes. René remained in second, but he was closing the gap between them with every lap, biding his time under Caracciola had to stop and refuel.

And then, the wildest decision came: When Caracciola pulled into the pit on lap fifty-two, he said he was done. He had suffered a devastating injury to his leg in a race several years before, and this race with all its braking and gear shifting was too hard on it. The spare German driver, Hermann Lang, should take over.

This was completely legal by race rules, but Lang wasn’t ready to go.70 He was in street clothes, fully expecting not to drive that day. While the mechanics refueled the car Lang changed as quickly as he could. By the time he got back on the course, René had been in the lead for a full minute.

When René noticed the name had changed on the lapboard though, he interpreted Caracciola’s withdrawal differently. He believed that the man couldn’t stand to be beaten by a French car, let alone one driven by a Jewish man named Dreyfus.71 Even if Caracciola wasn’t anti-Semitic himself, the Nazis wouldn’t have it. Annoyed by this, René’s anger convinced him to push harder.

Unfairly, René had also already been driving for over 90 minutes. It was grueling and he was tired; Lang was coming in fresh. He knew this was where a simple mistake would cost him the victory. But for now, his victory seemed assured: he was increasing his lead with every lap. Lang would have to drive like a man possessed, but there was only so much one could do driving on city roads.

When his lead had increased to a full three minutes, René began letting off his speed. He didn’t want to risk blowing a tire or the engine when it would be hard for the Mercedes to make up such a gap. The laps slipped by pleasantly and suddenly, it was over. He’d won the Grand Prix and set a new record time as well. More importantly to him, he had triumphed over Mercedes with a convincing margin of one minute and fifty-four seconds.72 So much for German preeminence or Jewish inferiority; he had won handily.

It’s easy to imagine Lucy screaming in celebration in Cannes. I wish she’d been there–it was such an important race for her, for France, for the fight against Fascism.

Two weeks later, René won another Grand Prix in Cork, Ireland. No German cars competed that day, but it still cemented Delahaye ascendancy over all the other marques–he’d beaten a Bugatti and a Maserati. And he’d done while, quote, “being sprayed by hot oil from a gear-box leak,” which sounds incredibly painful and dangerous.73 But then, that’s the whole sport of race car driving.

Unfortunately, Écurie Bleue didn’t fare that well for the rest of the season. Many of the races contained long straights, where the Mercedes power could be unleashed to carry the team into full podium finishes. However, in the only two races that the German teams didn’t win, it was René and the scrappy Écurie Bleue team who stood up to them. At the end of the season, René still earned the title Racing Champion of France, thanks to his two Grand Prix wins as well as his fourth-place finish at Mille Miglia and a first place finish at La Turbie.

In the middle of the season, the French government announced another million Franc prize. This time it wouldn’t be awarded based on a race or competition, but based on some loose measure of merit. Lucy felt sure that she would be awarded it based on Écurie Bleue’s huge successes that year, but it was awarded to Talbot on the basis of little more than some promising blueprints.

Lucy was “distraught.”74 Not only had she been counting on the money to develop more race cars, but she also took it as a personal affront. Clearly, the French government had issues with a woman running a racing team, even if they were successful. In protest, she withdrew the team from the French Grand Prix, but that didn’t change anything.

Écurie Bleue continued racing for another year, but Lucy was distracted throughout the 1939 season and the team didn’t do as well. Laury had gotten into a car accident while driving from Monaco to Paris; he seemed okay at first, only to wake up in the middle of the night and realize he was partially paralyzed.75

On September 1, 1939, the Nazis invaded Poland. France declared war on Germany soon after, and the world officially descended into World War II. Still in his mid-thirties, René was called up to serve in the French military. Less than a month later, Lucy and Laury were being driven from Monaco to Paris by their chauffeur and were in another terrible accident. Both Schells were seriously injured, and Laury died from his injuries a month later. Lucy was still in the hospital, too injured to leave for the funeral. It was Corporal René Dreyfus in his military uniform who stood with their two sons at the graveside.

The French government had watched German military movements throughout 1939 with anxiety. They quickly began safeguarding dangerous weapons and French national treasures, anticipating an attack. Art was moved out of the Louvre, government archives were burned, and supplies of uranium hidden or destroyed. Much of this would have been obvious to Parisians–hard to miss that the Louvre was suddenly empty. They followed the government’s lead, hiding family heirlooms underground or in countryside estates when they could. And corporations did too–Delahaye dismantled their four 145s, hiding them in caves and disguising their powerful engines in new bodies that probably looked less like racing cars that had defeated the Nazi Silver Arrows. After the war, the cars were rebuilt and, quote, “became instant classics of high art-deco design.”76 Because the cars were taken apart and put back together, it’s hard to say exactly which one René drove in that fateful race at Pau; quite possibly, the parts were split into all four 145s. Today, all four are in museums in the US.

When the Luftwaffe bombed Paris on June 3rd, 1940, they targeted the Renault and Citroën factories in west Paris, which had transitioned into war production. The Delahaye factory, where Weiffenbach was still working, was spared. Throughout the occupation of Paris, he participated in the resistance through, quote, “constructive non-cooperation,” making sure that the Delahaye factory wasn’t producing anything that could help the Nazi war machine.77 Many in the French racing industry did the same. Notably, the Gestapo also raided the headquarters of the Automobile Club de France where all records of France’s participation in Grand Prix racing were kept–including René’s win the year before. They wanted to erase France’s successful history in car racing, and the records were destroyed.78

In early 1940, Lucy had asked René to race one more time for Écurie Bleue. She somehow finangled leave from the military for him to travel to the US and compete in the Indianapolis 500. He traveled with her nineteen-year-old son Harry Schell. They were in the US when Germany invaded France. Distracted by the bad news coming out of Europe, René finished tenth at the Indy 500. He wanted to return to France immediately, but Lucy told him to stay in the US with her son for his own safety. Paris surrendered soon after and René found himself cut off and adrift, his bank accounts frozen. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the US military and was sent back to Europe to participate in the 1943 invasion of Italy. He became a US citizen and remained in New York after the war ended. He opened a restaurant in New Jersey and became a famous restaurateur. His memoir, My Two Lives: Race Driver to Restauranteur, covers both his careers and his life in between. He died in 1993.

Soon after the Nazi occupation of France, Lucy and her son Philippe fled to the US. They reunited with Harry and remained in the US until the war ended in 1945, though where they lived is not entirely clear. They returned to Monaco soon after. Lucy never raced again, though she did support her two son’s driving efforts. Harry was the first American to compete in a Formula 1 Grand Prix race and remained a prominent race car driver until he died during a practice session at Silverstone in 1960.79 Philippe also had a brief career as a Formula 3 driver in the early 1950s, though he wasn’t as devoted to it. What he did after he quit driving is unknown, but he passed away in 1991.

Lucy O’Reilly Schell died in Monte Carlo, Monaco, on June 8, 1952. She was initially interred in Monaco, but eventually, her remains were moved to a cemetery in Brunoy where the rest of her family, including Laury, was buried. Her sons were eventually buried there as well.

And that is the story of Lucy Schell! I know it’s been a while since the last episode; life just kind of got away from me in February and March. But I hope you liked this triumphant return, though it’s not nearly as moving as René’s was. If you liked this episode, please tell a friend about it. You can also let me know your thoughts by sending me a note. I’m on Twitter and Instagram as @unrulyfigures. You can also follow Unruly Figures on Substack, where I post tons of bonus content. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks find this work. Thanks for listening!

📚 Bibliography

Bascomb, Neal. Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler’s Best. Mariner Books, 2020.

———. “Lucy Schell: The Pioneering Rally Driver Who Beat the Nazis.” Car and Driver, May 31, 2020. https://www.caranddriver.com/features/a32690075/the-pioneering-rally-driver-who-beat-the-nazis/.

———. “On the Road with the Heiress Who Dominated Early Motorsports.” Literary Hub, March 20, 2020. https://lithub.com/on-the-road-with-the-heiress-who-dominated-early-motorsports/.

Blackstock, Elizabeth. “How Lucy O’Reilly Schell Used Motorsport To Fight Fascism.” Jalopnik, December 13, 2021. https://jalopnik.com/how-lucy-oreilly-schell-used-motorsport-to-fight-fascis-1848204620.

Historic Racing. “Lucy O’Reilly-Schell,” n.d. https://www.historicracing.com/driverDetail.cfm?driverID=7730.

“Motorsport Memorial - Harry Schell.” Accessed February 28, 2023. http://www.motorsportmemorial.org/focus.php?db=ct&n=215.

“Motorsport Memorial - Lucy O’Reilly Schell.” In Motorsport Memorial, n.d. http://www.motorsportmemorial.org/LWFWIW/focusLWFWIW.php?db=LWF&db2=ct&n=436.

“Motorsport Memorial - Philip Schell.” Accessed March 25, 2023. http://www.motorsportmemorial.org/LWFWIW/focusLWFWIW.php?db=LWF&db2=ms&n=1021.

Nix, Elizabeth. “What Was the Dreyfus Affair?” HISTORY, August 22, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/what-was-the-dreyfus-affair.

Shacki. “Final Results Critérium International de Tourisme Paris-Nice 1934.” eWRC-results.com. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://www.ewrc-results.com/final/66902-criterium-international-de-tourisme-paris-nice-1934/.

———. “Final Results Critérium International de Tourisme Paris-Nice 1935.” eWRC-results.com. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://www.ewrc-results.com/final/66852-criterium-international-de-tourisme-paris-nice-1935/?ct=6432.

WRC - World Rally Championship. “Rallye Monte-Carlo,” n.d. https://www.wrc.com/en/championship/calendar/wrc/rallye-monte-carlo/overview/.

FYI: A few of the links in this post are affiliate links. That just means if you click through a buy a book, I’ll get a few cents of profit but it won’t cost any more for you.

Bascomb, Neal. “On the Road with the Heiress Who Dominated Early Motorsports.” Literary Hub, March 20, 2020. https://lithub.com/on-the-road-with-the-heiress-who-dominated-early-motorsports/.

Bascomb, LitHub.

Bascomb, LitHub.

Blackstock, Elizabeth. “How Lucy O’Reilly Schell Used Motorsport To Fight Fascism.” Jalopnik, December 13, 2021. https://jalopnik.com/how-lucy-oreilly-schell-used-motorsport-to-fight-fascis-1848204620.

Bascomb, Neal. Faster: How a Jewish Driver, an American Heiress, and a Legendary Car Beat Hitler’s Best. Mariner Books, 2020.

Historic Racing. “Lucy O’Reilly-Schell,” n.d. https://www.historicracing.com/driverDetail.cfm?driverID=7730.

Bascomb, LitHub.

Bascomb, Car and Driver.

Faster, 85

Faster, 85

Blackstock

Faster, 59

Faster, 84

Faster, 84

Blackstock

Faster, 68

Faster, 70

Faster, 84

Faster, 87

Faster, 77

Nix, Elizabeth. “What Was the Dreyfus Affair?” HISTORY, August 22, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/what-was-the-dreyfus-affair.

Faster, 93

Faster, 95

Faster, 94

Faster, 104

Faster, 96

Faster, 100

Faster, 101

Faster, 102

Faster, 110

Faster, 114

Faster, 116

Faster, 117

Faster, 126

Faster, 127

Faster, 120

Faster, 120

Faster, 121

Faster, 121

Faster, 125

Faster, 125

Faster, 125

Faster, 141

Faster, 141

Faster, 141

Faster, 150

Faster, 152

Faster, 160

Faster, 164

Faster, 165

Faster, 165

Faster, 165

Faster, 166

Faster, 167

Faster, 180

Faster, 181

Faster, 182

Faster, 187

Faster, 173

Faster, 192

Faster, 193

Faster, 194

Faster, 197

Faster, 197

Faster, 227

Faster, 230

Faster, 235

Faster, 237

Faster, 249

Faster, 254

Faster, 254

Faster, 256

Faster, 260

Blackstock

Faster, 262

Faster, 271

Faster, 268

Blackstone

“Motorsport Memorial - Harry Schell.” Accessed February 28, 2023. http://www.motorsportmemorial.org/focus.php?db=ct&n=215.

Share this post