Hi everyone,

I am so excited for y’all to hear this week’s episode! I love a little bit of mysterious and potentially supernatural history, so this one is RIGHT up my alley. I’m publishing it at night because, well, scary stories are always a little scarier in the dark, right? 👻

Have you told anyone about Unruly Figures yet? As a little spooky season gift to me, tell one person about the podcast! This is a great episode to get someone hooked.

🎙️ Transcript

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m covering the mysterious Herman the Recluse, and the deal he supposedly did with the Devil to create the Codex Gigas, better known as The Devil’s Bible. It’s a perfect story for Halloween.

But before we jump into his life and the mystical things he might have done with Satan’s help, I want to give a huge thank you to all the paying subscribers on Substack who make this podcast possible: Katie, Ana, Mike, Jim, Daniel, Casey, John, Andrew, Stefan, Skyler, Elizabeth, Honor, Neal, Michael, Reda, and Sarah. Special shout out as well to founding-level subscribers Nick and Erick. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t be possible without you! If you want to support Unruly Figures and my mission to make exciting history more available to folks, you can do that at unrulyfigures.substack.com Becoming a paying subscriber will also give you access to exclusive content, subscriber-only polls, merch, and behind-the-scenes info on the podcast.

I want to give a quick trigger warning to everyone–I do mention child sexual abuse in here. I don’t talk about it for long, it’s not a graphic discussion, and the person we’re talking about today is probably not guilty of this crime. I will give a warning when it comes up if you would be more comfortable skipping ahead.

All right, let’s hop back in time.

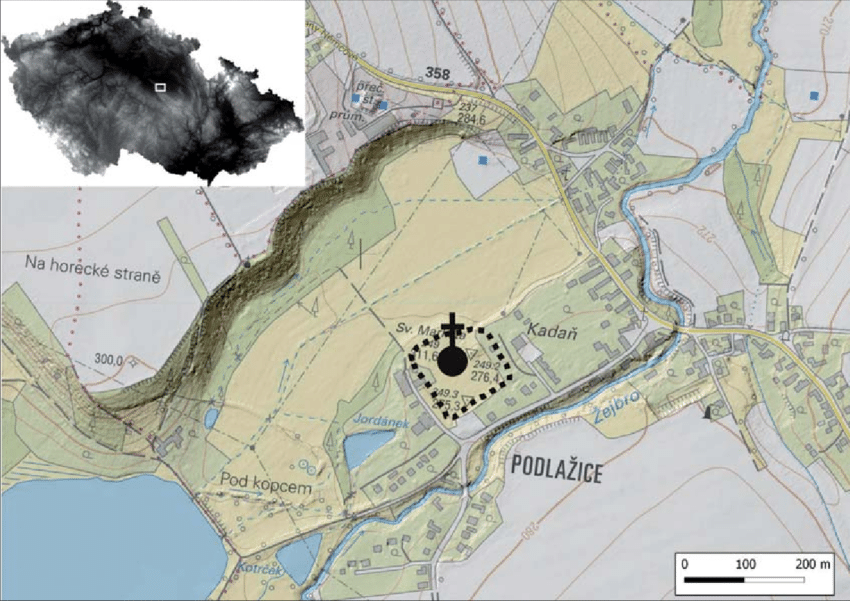

We’re going all the way back to 12th or 13th century Bohemia, to Podlažice ] to be exact. Podlažice is a small village in today’s Czech Republic. At the time, it was home to a Benedictine monastery, though that monastery has since disappeared. It’s famous, however, as the place where a certain monk, Herman, spent a harrowing night doing penance–or selling his soul to create the famous Codex Gigas.

At this point you might be wondering what the heck ‘Codex Gigas’ means, and that’s totally understandable because ‘codex’ sounds like a word that Dan Brown made up for The Da Vinci Code. But a codex is basically just a handwritten book, which replaced scrolls in the fourth century. Though papyrus scrolls were durable, they were, well, annoying–once read, they had to be rolled back up, and the act of constantly rolling and unrolling the scrolls caused wear and tear that broke them down eventually. Scrolls could also only have text on one side, which we all know is inefficient, and there wasn’t a uniform way of marking a place in a scroll. I know in Harry Potter Professor Snape is constantly assigning people essays like “12 inches on the uses of dittany,” but when scrolls are more than a foot long, citing where in a scroll someone says something presents issues.1

So the Romans invented the notebook by substituting parchment for papyrus. They would create large sheets and fold them to create folios, quartos, and octavos. Stitched together and protected by a cover, sometimes made of wood, these notebooks gained popularity for accounting, drafting text, and letters.2 Because of its resemblance to a block of wood (a caudex in Latin), these little tablets or notebooks came to be called codexes or codices.3

Codices didn’t really get popular until the rise of the early Christian Church, which used the codex style for early Bibles exclusively. They did this because the scroll was associated with Jewish religious texts and pagans and the church wanted to visually differentiate themselves from those traditions.4 The codex was also practical–it was easier to store longer texts in one codex than in a single scroll. I mean, imagine trying to roll up a single scroll for the Old and New Testaments. The codex was handy and it made recording and preserving knowledge much less daunting. Until the invention of the printing press, however, these were necessarily made by hand.

So that’s codex. And then ‘gigas’ is Latin for ‘giant.’ And the book I’m going to tell you more about soon is giant–it weighs in at 75 kilograms or 165 pounds. One hundred and sixty-five pounds! That’s more than me. The book is about three feet tall, 20 inches wide, and nine inches thick. I’m going to put a photo of a woman standing next to it in the transcript because it has to be seen to be believed. It’s the largest known and preserved medieval manuscript that we have. So yeah, Giant Book works as a title, though The Devil’s Bible is a much more popular name.

Unfortunately, we don’t know much about Herman at all. We’re talking about an almost 800-year-old story, so that’s to be expected, but we can make some educated guesses about him: He may have been genuinely a deeply religious person. Joining a monastic order is not a light decision, and his epithet ‘the Recluse’ sounds like he might have even been an anchorite, a monk or nun who was enclosed into a cell attached to a church so that they could always be found. As we’ll see, there’s reason to believe this might not have been a voluntary withdrawal from society though. Before taking vows, he might have come from a poor family–when Medieval parents of children couldn’t afford to feed them, they sometimes enrolled them in monastic orders not just to get an education but to make sure the kids could eat and live.5 Children as young as five could be taken into monastic orders, but more often they came as preteens.6 Sometimes we also see younger sons in wealthy families taking up religious vocations because they weren’t going to inherit anything when their fathers died, but they didn’t have to become monks. Other jobs, like the priesthood, would have been open to Herman after receiving this education, so it seems likely that he became a monk because he wanted to.

In his mid-teenage years, Herman would have been a novitiate, someone educated in the ways of monastic life but not subject to all the rules monks follow. After a year of this education, he would have been eligible to take the full vows and become a monk, which he clearly did. He might have never left the monastery again, as monks were expected to live within their communities unless they were excommunicated.

Benedictine monks could expect an autonomous life from the outside world, but a good community within the monastery. The Order of St. Benedict is a pretty decentralized organization, as opposed to Catholicism where everyone comes under the Pope in Rome, abbots of Benedictine monasteries have the right to set their own rules for the community, deciding what books to read, what prayers are said, et cetera. The only requirement is that they follow the rule devised by Benedict of Nursia in the late fifth century. That can be summarized as “ora et labora” or prayer and work.7 Initially, Benedictine monks were expected to live lives of simplicity, in a quote, “shared community of mutual aid and watchfulness, participating in the physical labour needed to make the monastery economically self-sufficient as well as undertake religious studies and prayer.”8

But, really quickly monasteries grew in wealth and power. The wealthy believed that they could ensure their entrance into heaven if they made great gifts to religious orders, so monasteries became the owners of huge swaths of land, luxurious reliquaries, stockpiles of gold, and more. Technically, the members themselves were poor and everything was held communally, with the abbot administering it. In practice, this meant that these orders could, uh, buy slaves who did all the manual labor for them, freeing the monks up for more contemplation and writing.9 This is how we get the rise of breviaries and illuminated manuscripts.

The 12th century was when the Benedictine order was considered to be at its most prominent. The century after, when our story probably takes place, is seen as a moment of decline and decadence for the Benedictines.10 But until then, the Benedictine monasteries were seen as, quote, “the chief repositories of learning and literature in western Europe and were also the principal educators” of people who could send their children to be educated.11

So this is the world Herman was living in: An order in slight decline, probably trying to desperately recapture the glory of their former power.

At some point along the way, Herman did something bad. He broke a rule that earned him a punishment from the abbot of his monastery. What exactly he did isn’t specified, though it seems to have been breaking some monastic vow.

If you’re uncomfortable with any mention of sexual abuse, now would be the time to skip ahead about a minute.

So, since the only vows Benedictine monks took were poverty, chastity, and obedience, and poverty and wealth were out of his control, I think we can guess this was a break with chastity, obedience, or both. I know what you might be thinking, but knowing what we know about the sexual abuse scandals within the Catholic Church, it’s actually possible that Herman’s crime wasn’t abusing someone but actually reporting it to outside powers. By the Medieval era, church leaders and monasteries were already dealing really badly with the predatory behavior of adult men against young boys. Dyan Elliot, author of The Corruptor of Boys, explained in an interview that, quote,

[monastic] organizations were generally self-policing, and worked hard to ensure that instances of the clergy’s sexual predation were suppressed. Monasteries were especially secretive, making it a heinous offense to reveal any discipline meted out in chapter to outsiders. Cases of clerical sodomy were only prosecuted when the scandal spread to secular society or when the guilty cleric was being investigated for something else.12

End quote.

A cleric assaulting a young boy would have been considered a scandal and crime among secular society at this time, so it’s possible that the great crime Herman committed was telling someone outside of the monastery about abuse that was going on within. It would have broken the rule of obedience to his abbot, which would have triggered a punishment before Herman actually assaulting someone would have.

Whatever his crime, Herman was condemned to be walled up in the monastery, a forced anchorite. There are different versions of this punishment: Some say he was to spend the rest of his natural life there, working alone and in silence. Others say he was walled up to be starved to death, essentially the death penalty for his crime.

No matter the initial length of his sentencing, Herman begged the abbot for a chance to redeem himself. He promised to create a great codex that would contain all human knowledge and glorify the monastery forever. So he was locked into a room with some vellum and some ink and allowed to try. Again, lengths of time vary here. Some say he had only a year to do this, some say a week, but most say Herman had a single night to record all knowledge in the world and save himself.

Well, midnight approached and at the other side of it lay a dawn that would lead to his death. And Herman was nowhere near done. Illuminated manuscripts take time, babe, and he couldn’t have completed a single page in one night. So Herman began to pray. Not to God, but to Satan. He offered up his eternal soul in return for the book to be completed by dawn.

And it was. Legend has it that the Devil agreed to help and signed his work with a selfie–there’s a full-page illustration of the Devil within, right in the center of the book, in a folio that is otherwise empty. In the image, he is not in Hell, which is strange for the time. He’s shown between two columns and wearing ermine, a type of fur that was reserved for royalty.13 Very strange for a monk to dress the Devil this way. Across from the Devil is a full-page image of the Kingdom of Heaven, but–and if you’ve ever looked at medieval art, you’ll find this really startling–the Kingdom of Heaven seems to be entirely empty.14 When the codex is closed, the Devil is sort of “inside” the empty Kingdom of Heaven, which is an unsettling image for a monk to be making.

It was done. Herman was damned for eternity, but his Codex was done. All 320 pages on vellum were complete, with both the Old and New Testaments, the Encyclopedia of St. Isidore, a history of the Jewish people, a contemporary history of Bohemia, early medical texts, a comparative alphabet, a calendar, over 1500 obituaries, a list of monks in the monastery…and a five-page long confession of sins, a few spells from old Christian and Jewish tradition, as well as some instructional guides for exorcisms. As Curt Sanvidg pointed out in his episode of Paranormal Almanac on the Codex Gigas, a lot of people see the inclusion of exorcism in there as proof that the devil wrote it, which he thinks doesn’t make sense. Why would the devil give you instructions for how to get rid of demons, after all? I posit that if the devil did indeed have his hand in this book, then the instructions are a trick and don’t work. The devil’s around to torture, after all, and what’s more torturous than false hope?

The five-page long confession of sins is intense. It is a full listing of every sinful thought, word, and act Herman committed, and includes pride, envy, gluttony, lust, and bestiality.15 (I don’t read Latin so I am not 100% sure, but the National Library of Sweden didn’t mention if this list includes same-sex desire.) Confessing sins isn’t an unheard of practice within Christianity, of course, but something about how long this is, confessed one right after the other, in writing, surprises me. I wish we knew if the sins were in order. Did he start at birth and continue up to that night? Did he leave room on the page so he could go back and keep adding sins as he committed them? We’ll never know.

Anyway. I wish we knew how the abbot reacted when he unlocked the door and found Herman with his completed Codex. I imagine that Herman, newly unpossessed by the Devil, was slumped over unconscious, and that the Gigas was open to that image of Satan, surrounded by empty ink bottles.

It’s worth noting that this legend originated in the twelfth century and has remained virtually unchanged since. Centuries of scholars have studied this work and agreed with the original legend: Herman did it in a single sitting, which could only be possible if Satan was helping him. Just the fact that this oral tale hasn’t changed much over the years is pretty impressive.

We don’t know what became of Herman–was he allowed to live after creating this? We do know that the Monks of Podlažice pawned the manuscript to a Cistercian Monastery nearby when they were facing a financial crisis in 1229.16 It was repurchased the same year by the Archbishop of Prague and returned to the Benedictine Order, but to the Benedictine Monastery in Břevnov, which was famously quite rich.

Around 1594, King Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, requested the use of the Codex Gigas. He was interested in alchemy and had become obsessed with the image of the devil the Codex contained. He never returned it. During the Thirty Years’ War, it was carried off by the Swedish army as the spoils of war for Queen Christina. It has remained in Sweden ever since.

But on Friday May 7, 1697, a terrible fire broke out at the castle in Stockholm. Some enterprising librarians tried to save the collection, but the fire was spreading too fast and the collection too huge. Unable to pack the books up to safely get them out, they began throwing the books out of windows, including the Codex Gigas. Supposedly, the book landed on someone below, severely injuring or even killing them. Of course, the binding was damaged in this act, and several pages of the book possibly came out. In fact, a lot of art dealers and historians think that at least some of these pages are out there, held in private collections. If your family has one of these pages, please send an anonymous photo in, we all went to know what’s on them.

Today it’s behind bulletproof glass in the Swedish National Library, where you can go see it if you’re ever in Sweden.

And it’s worth seeing because the book is really beautiful. It’s bound with wood, as all codices were, that’s been covered in white leather. The leather is embossed with a diamond pattern and crowns and maybe the royal insignia of the house of Hapsburg? I’m less sure about what this symbol is, but it looks like a royal insignia to me. The four corners of the front cover have a metal fitting with two griffins each, and there’s a metal eight-point star in the center of the cover. The inside is also beautiful. I’m going to read a long quote from a librarian here, Binghamton University, because they’ve described the inside better than I could. So, it contains, quote,

illuminations in red, blue, yellow, green and gold. Capital letters at the start of books of the bible and the chronicle are elaborately illuminated in several colours, sometimes taking up most of the page; 57 of these survive (the start of the Book of Genesis is missing). There are also 20 initials with the letters in blue, with vine decoration in red. With the exception of the portraits of the devil, an author portrait of Josephus, and a squirrel perched on top of an initial (f. 110v), the illumination is all using geometrical or plant-based forms, rather than representing human or animal forms. There are also two images representing Heaven and Earth during the Creation, as blue and green circles with respectively the sun moon and some stars, and a planet all of sea with no landmasses.17

The National Library of Sweden has digitized every page of this book, so if you want to take a look there are 629 high-resolution photos that you can check on online. I’ll include a link in the show notes. They also have a fifteen-minute film you can check out. It’s in Swedish with English subtitles, but it’s worth a watch if you’re really into this book. Again, link in the show notes.

As I mentioned, we really don’t know what became of Herman the Recluse. I hope he went on to live out his natural life, but we’d have to dig through old monastic documentation to find out. Unfortunately, the monastery in Podlažice has vanished. It was destroyed during the Hussite Revolution in the 1430s.

Before we close out, I’m going to go over some facts and stories about the book:

The depiction of the Devil in it is thought to be one of the only Medieval depictions of the Devil in the Bible.

According to the National Library in Sweden, the whole book was written all in one hand, there’s no evidence that anyone took over at any point. The writer also seems to have been in a stable mood the whole time–the handwriting doesn’t get sloppy, there’s no authorial doodles, no sign that the hand that wrote it ever got tired or injured or sick. I can’t overstate this: this wasn’t written in shorthand, it’s not like…scrawled notes. The handwriting is beautiful…and tiny. It was written in Latin in something called Carolingian Miniscule.18 This lends some support to the theory that it was written in a short time, even though any rational estimation would suggest that writing a book this size by hand would take about thirty years of work.

Here’s where it gets weird: The writing should show aging. If it was done over thirty years by a single scribe–the second part proven, the first part the only rational amount of time that anyone can come up with–the text should have at least gotten larger as he aged and his eyesight declined. But it’s all the same size.

More strangely, the Codex Gigas has been combed through by historians and ecclesiastical experts and there are no mistakes, nor omissions. He didn’t spell a single word wrong, he didn’t conjugate Latin incorrectly, he didn’t skip anything while copying. The text is flawless, from first page to last, which is pretty strange. This should be impossible! No mistakes in thirty years?! C’mon! This can’t be explained.

Remember that fire in Stockholm I mentioned? Okay, so, the story goes that the book was thrown out the window, probably by several people working together, right? And they resorted to this because the fire and smoke were spreading too fast. Well, the book has no discernable smoke or fire damage. No evidence of ever having been near a fire in eight hundred years. None. Which, again, should be impossible, because it’s well documented that the book survived this fire. And somewhere along the way someone read this thing by candlelight by a fireplace, which should infuse at least a little smoke into the vellum. But somehow, it didn’t! This of course further fuels the rumors that the book was written by the Devil and is still protected by him.

Remember those ten missing pages I mentioned? Well, there’s some thought that they didn’t come out during the fire in Stockholm. In fact, the National Library of Sweden has confirmed that a lot of those pages were deliberately cut out, not ripped out. It’s likely that the rules of the monastery were included in these pages, but Benedictine monastery rules were generally very simple, they wouldn’t have taken up all ten pages. We also know that the beginning of the Book of Genesis is now missing, but was originally included.19 So we don’t know what else is missing. It could be anything. Naturally conspiracy theories have popped up around what could possibly be in these missing pages, including, quote, “secrets too explosive for mere mortals to know; magic spells; instructions for the apocalypse.”20 Again, if your family has any of these missing pages in a Swiss vault somewhere, call me. I won’t turn you in. But we’ve got to see these.

One last spooky story related to the Devil’s Bible. Apparently, in 1858, a guard in the library fell asleep on the job and was accidentally locked inside the library after closing. When he woke, all the books were swirling around in the air, led by the Codex Gigas and the Devil himself. When the guards reopened the library the next morning, they found the guard hiding under a table, disturbed by what he’d seen. The listened to his story patiently and tried to restore him to sense, saying it was a hallucination. But, quote, “all efforts to restore him to his senses proved to be fruitless.”21 The guard had to be institutionalized and never recovered.

As I mentioned, today the Codex Gigas is displayed behind bullet-proof glass and underground to protect it from damaging UV rays. If you’re ever in Sweden, you can see it yourself–I know it’s on my travel list now.

If legends are to be believed, Herman the Recluse created the Codex to ensure that his monastery in Podlažice would never be forgotten. And 800 years later, it looks like it never will be.

And that is the story of Herman the Recluse and his deal with the devil. Happy Halloween, I hope this spooky episode got you in the mood for the holiday this weekend. If you dress up as a historical figure this year PLEASE tag me in your photos, I’m dying to see them. I myself am planning to dress up as Anne Boleyn, and I will of course be posting photos on the Unruly Figures Instagram.

I hope you enjoyed this episode of Unruly Figures! If you did, please tell a friend about it. You can also let me know your thoughts by following me on Twitter and Instagram as @unrulyfigures, or joining us over on Substack. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks find this work. Thanks for listening!

🔗 Links

High-res photos of the Codex Gigas from the National Library of Sweden.

Short film about The Devil’s Bible from the National Library of Sweden.

📚 Bibliography

Podcasts

“The Codex Gigas/The Devil's Bible.” Paranormal Almanac, created by Curt Sanvidg, episode 71, 2 Jan. 2019. https://www.scribd.com/listen/podcast/594008294

Videos

“Codex Gigas.” – Kungliga Biblioteket – Sveriges Nationalbibliotek – Kb.se, National Library of Sweden, 27 Sept. 2018, https://www.kb.se/in-english/the-codex-gigas/film-about-the-codex-gigas.html.

Websites

“Benedictine.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/Benedictines.

Cartwright, Mark. “Medieval Monastery.” World History Encyclopedia, Https://Www.worldhistory.org#Organization, https://www.worldhistory.org/Medieval_Monastery/.

East, Michael. “The Truth about: The Devil's Bible.” Medium, The Mystery Box, 28 Feb. 2021, https://medium.com/the-mystery-box/the-truth-behind-the-devils-bible-530a423df80c.

Elliot, Dyan. Notches Blog, 10 Nov. 2020, https://notchesblog.com/2020/11/10/the-corrupter-of-boys-sodomy-scandal-and-the-medieval-clergy/ .

Grout, James. “Scroll and Codex.” Encyclopaedia Romana, University of Chicago, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/scroll/scrollcodex.html.

“Herman the Recluse.” Lost Manuscripts, 25 May 2016, https://lostmanuscripts.com/tag/herman-the-recluse/.

Leigh, Lex. “Medieval Monks: The Life and Times of God's Men in Robes.” Ancient Origins, Ancient Origins, 17 July 2022, https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/medieval-monks-0017025.

“Podlažice (Chrudim District). .” ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Podlazice-Chrudim-district-The-complex-of-the-vanished-Benedictine-monastery-is_fig1_338342256.

Sorabella, Jean. “Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe.” Metmuseum.org, The Met Museum, Oct. 2001, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mona/hd_mona.htm.

“The Codex Gigas (Aka the Devil's Bible).” Special Collections News, Binghamton Library News, 30 Oct. 2017, https://libnews.binghamton.edu/specialcollections/2017/10/30/the-codex-gigas-aka-the-devils-bible/.

Grout, James. “Scroll and Codex.” Encyclopaedia Romana, University of Chicago, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/scroll/scrollcodex.html.

Grout

Grout

Grout

Leigh, Lex. “Medieval Monks: The Life and Times of God's Men in Robes.” Ancient Origins, Ancient Origins, 17 July 2022, https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/medieval-monks-0017025.

Leigh

Sorabella, Jean. “Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe.” Metmuseum.org, The Met Museum, Oct. 2001, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mona/hd_mona.htm.

Cartwright, Mark. “Medieval Monastery.” World History Encyclopedia, Https://Www.worldhistory.org#Organization, https://www.worldhistory.org/Medieval_Monastery/.

Cartwright

“Benedictine.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/Benedictines.

“Benedictine”

Elliot, Dyan. Notches Blog, 10 Nov. 2020, https://notchesblog.com/2020/11/10/the-corrupter-of-boys-sodomy-scandal-and-the-medieval-clergy/ .

“‘The Codex Gigas/The Devil's Bible.’” Paranormal Almanac , created by Curt Sanvidg, episode 71, 2 Jan. 2019. https://www.scribd.com/listen/podcast/594008294

Sanvidg, minute 16.

“Codex Gigas.” – Kungliga Biblioteket – Sveriges Nationalbibliotek – Kb.se, National Library of Sweden, 27 Sept. 2018, https://www.kb.se/in-english/the-codex-gigas/film-about-the-codex-gigas.html.

East, Michael. “The Truth about: The Devil's Bible.” Medium, The Mystery Box, 28 Feb. 2021, https://medium.com/the-mystery-box/the-truth-behind-the-devils-bible-530a423df80c.

“The Codex Gigas (Aka the Devil's Bible).” Special Collections News, Binghamton Library News, 30 Oct. 2017, https://libnews.binghamton.edu/specialcollections/2017/10/30/the-codex-gigas-aka-the-devils-bible/.

Kungliga Biblioteket, minute 4

Binghamton Library

“Herman the Recluse.” Lost Manuscripts, 25 May 2016, https://lostmanuscripts.com/tag/herman-the-recluse/.

Kungliga Bibioteket, 10:30-10:45

Share this post