Hello everyone,

Happy New Year! Welcome to 2024 and another episode of Unruly Figures. I’m sorry this one is late, I completely lost track of time during that week between Christmas and New Years’—that yesterday was Tuesday was a big surprise to me. 😂

In any case, let’s get started because I am *so* excited to introduce you to Noor Inayat Khan!

Like many spies in World War II, Noor Inayat Khan’s story was kept under a veil of war secrets for several years. But once her story broke, it became a sensation. There are countless TV and film adaptations of her mission and tragic death, as well as several biographies. London is littered with plaques and statues devoted to her. She’s been honored and thanked for her services by many groups, including an annual Sufi urs—memorial service at a convent near Dachau. Just last year, Queen Camilla unveiled a new portrait of Noor at the Royal Air Force Club and announced that a room would be named in her honor.

But who was Noor Inayat Khan beyond her tale of heroism and sacrifice? Let’s find out.

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Castellanos Clark, and today I’m covering Noor-un-nissa Inayat Khan, better known as Noor Inayat Khan, the spy princess. She was a talented musician, a devoted Muslim, a descendant of Indian royalty, and a spy for the British during World War II.

But before we jump into Khan’s life and her dramatic contributions to the Allied victory, I first have to thank all the paying subscribers on Substack who help me make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! If you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber over on Substack! When you upgrade, you’ll get access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates on the upcoming Unruly Figures book. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

If you like this podcast, you are going to love the Unruly Figures book—it’s full of 20 profiles of courageous rebels and rulebreakers that I’ve never covered here on the podcast. Coming out March 5, 2024 wherever books are old. Preorder yours now!

All right, let’s hop into it.

Noor Inayat Khan was born on January 1, 1914 in Moscow. Her full name, Noor-un-nissa, means Light Among Nations, which feels prophetic given how her story goes.1 Her parents were not Russian—her mother, Pirani Ameena Begum had been born Ora Ray Baker in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her family was very spiritual (in fact, her cousin Mary Baker Eddy founded the Christian Science Church), and it was in pursuing Sufi mysticism that Baker had met Noor’s father, Inayat Khan. It was from his side of the family that Noor gained her royal heritage—her great-great-great-grandfather was Tipu Sultan, the ruler of Mysore who died resisting British invasion. Inayat Khan was a Sufi mystic. When Ora ran away to marry Inayat, her family disowned her and she never saw them again; she took on the name Pirani soon after.

But Pirani never really got over this rupture in her life. Inayat’s brothers, who lived with them, also never really liked Pirani, finding her far too American in general; they treated her like a servant in her own home forcing her to take care of them as well as her husband and—soon—her four children. Inayat, whom Pirani loved obsessively, was away a lot, traveling to spread Sufi teachings in the West, and so Pirani was often depressed and struggled to get out of bed. This left Noor in charge of her three younger siblings a lot, as well as often in charge of trying to cheer Pirani up. She often wrote Pirani poems, including one on her birthday every year. Noor genuinely loved Pirani, but it was also one of her father’s teachings: “Always be more devoted to your other than even to your own prayers.”2

A lot of biographies focus pretty heavily on Inayat’s teachings, including the one I relied on for this episode: Code Name Madeleine by Arthur J. Magida. Noor was pretty devout, and also adored her father, so understanding what she learned from him is a key part of unlocking her own choices as a child and adult. However, I also don’t think we need to spend five minutes on it—Inayat taught Noor (and his thousands of followers) that love, harmony, and beauty were at the center of all things.3 Though he instilled the family’s royal heritage in his kids, he also ensured they understood that their role in the world was to help others, and that they were, quote, “oligated to be compassionate, to lift up others spiritually, to help anyone who was in pain or doubt;” they were always to be ready to sacrifice their own comfort to help someone else.4 This was their sacred duty, and Noor always took it very seriously. Importantly, Inayat’s Sufism was not dogmatic—anyone from any other religion was welcome, and after the family moved to France in 1920, he hosted some of his most devoted followers near his home every summer. Inayat was also a talented musician, initially leaving India by traveling in a band with Mata Hari, and he later became good friends with the composer Claude Debussy.5

Inayat saw the divine in most things. When Noor was just two months old, still living Moscow, he declared to his group of fellow theosophists that Noor was already a mystic; rather than doubtful, the theosophists were impressed—for them, a baby could be a mystic.6 For Inayat, “every baby was a mystic.”7 [Emphasis Magida’s.] Khan family lore even says that Noor saved the entire family a few short months later; as they left Russia in an elegant carriage, they were harassed by starving peasants; Inayat stepped out of the carriage and showed the crowd the infant—and they pulled back, allowing the child to pass safely.8 Divinely blessed or not, Inayat raised Noor accordingly. All this together left Noor with a love for beauty through music and art, as well as a firm commitment to peace, equality, and love. All values which would be tested in Europe of the 1930s and 1940s.

They had fled Russia due to the outbreak of World War I; England seemed safer. The family settled in Notting Hill, London, which then was, quote, “not much more than a slum.”9 In 1916, Noor’s brother Vilayat was born, and in 1917 her brother Hidayat was born. Finally in 1918, Noor got her greatest wish—a baby sister, Claire.10 Nevertheless, Noor and Vilayat would always be “preternaturally close” due to their shared interest in Sufism and the family’s mystical legacy.11

Noor largely did well in school; her teachers felt she was “too talkative” and had difficulty focusing on schoolwork, but she was diligent, intelligent, and kind.12 She was, quote, “neither disliked nor exceptionally popular, thought she was apparently respected: one year, she received the Good Comrade prize.”13 When World War I ended, the family moved to a suburb of Paris, Suresnes. Mount Valérian looms over the suburb, or rather, the suburb climbs the mountain. This area has always attracted spiritually devoted people—centuries ago, the mountain was the home of a Druid temple, and now a monastery stands on the site of that temple. The family home there, named Fazal Manzil, still stands about halfway up Mount Valérian and is still an important center for Sufi practice. Throughout Noor’s childhood, the family lived off the generosity of believers, which could be a feast or famine situation. This house and the grounds it sat on were on the feast side—it was gifted to them by Mrs. Petronella Engeling, a wealthy Dutch woman who had dedicated her life to Inayat and his work.14

I also want to note that there are some reports that Inayat relocated the family to France because he was facing increased surveillance from the British government.15 He was an outspoken advocate for Indian independence, which the British didn’t like, and in fact will come again for Noor. Regardless of why, the family moved to France.

Nearby Fazal Manzil, Noor befriended Raymonde Prenat, who was nearly the same age as her and attended the same school. Like most of the town, Raymonde was a French-born Catholic, and her family was probably middle class. They remained friends for the rest of their lives.

In September 1926, when Noor was 12 years old, her father Inayat returned to India for some rest and to reconnect with his spiritual center. He had been traveling nonstop, constantly teaching and receiving pilgrims, and he was exhausted. He sought solitude.

But he was too famous—people found out where he lived and approached him about giving concerts and lectures. He agreed, then caught a respiratory infection at one. It developed into pneumonia, and he died three weeks later.16

Back in Suresnes, the family was devastated. The children were left to cope on their own—their uncles were too busy jockeying for dominance over Inayat’s legacy to watch over them, and Pirani withdrew into herself; some people claimed she’d had a nervous breakdown.17 Noor took her mother’s place, and her siblings began to refer to her as “Little Mother.”18

Noor had always loved poetry and music—I mentioned the poems she wrote for her mother earlier. Until this moment, her poems had the stuff of children’s fantasy: Interactions with fairies dominated her writing. She was a dreamy child. But with this abrupt shove into adulthood, Noor’s poems became seeking, meditative, and searching. In one she begged, quote, “mystery of the night…breathe out to me…your mystical secret.”19

In 1928, Noor’s family—siblings, mother, uncles—set out on a pilgrimage to her father’s tomb in Delhi. Her uncles wanted Inayat’s Western-born children to know more about their homeland, as well as give them a chance to say goodbye to their father. But they also had another plan: Getting Noor engaged to a cousin she’d never met, Alladad Khan.20

The two kids met and became friendly in 1928. The plan was that Inayat’s children would move to Nepal, where he was part of the royal court; they could attend an English-speaking school in Kathmandu, and when she was old enough, Noor would marry Alladad. Through him, she would inherit the bulk of the Khan family wealth that her father had left behind. Noor had been a princess in name only until this point; this marriage would be something of a resurgence of political power for this line of the Khan family.

But her mother refused. She would not be separated from her children, and there was no place for her in Nepal. Noor’s uncles were infuriated, but I want to just point out here that the kids were young, around 14, 12, 11, and 10—if I was their mother, I wouldn’t want them separated from me living on another continent, being raised speaking a language I didn’t understand, moving about a royal court where I couldn’t protect them either. I get Pirani’s concerns here; her uncles were trying to use Noor and her siblings as pawns. They just wanted to cut Pirani out of the family inheritances that would have been Inayat’s upon the death of elder members. This rift was unbridgeable, and Noor spent years trying to keep the peace in an incredibly unpeaceful household.

Back in France, Noor graduated from high school in 1931. She went on to study child psychology at the Sorbonne—like her father, she had always believed that children possessed wisdom and a divine spark.21 She took music lessons at the Ecole Normal de Musique, studying under the legendary teacher Nadia Boulanger; just for an idea of how influential this woman was, Boulanger’s other students included Leonard Bernstein, Quincy Jones, and Philip Glass, some of the most incredibly composers of the 20th and 21st centuries.22 There are many photos of Noor playing her veena, an Indian instrument that looks a little like a lute. But under Boulander, Noor studied the harp, she was an incredibly gifted harpist. Her siblings also played instruments, and the four would often give small concerts for the family and any students in residence at Fazal Manzil.23

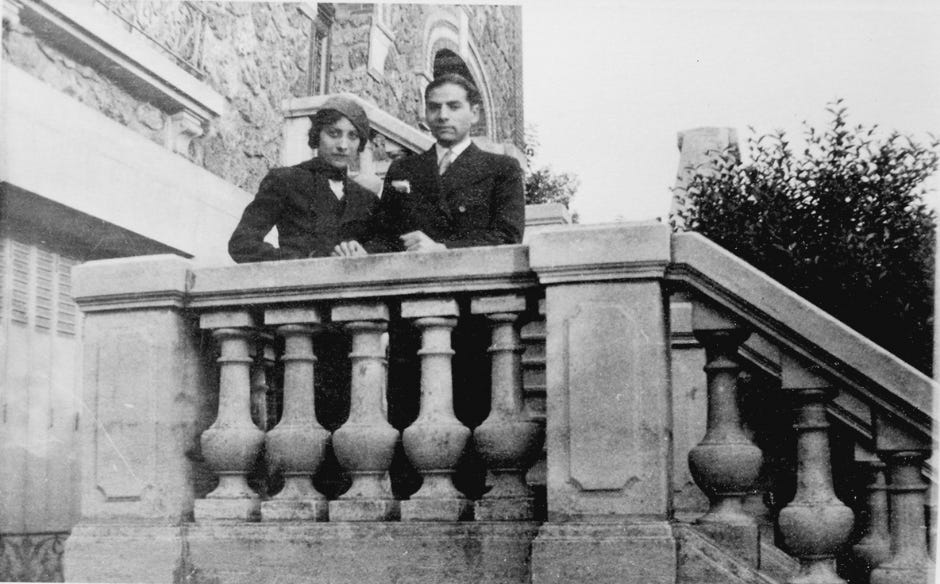

While studying the harp at Ecole Normal de Musique, Noor met Elie Goldenberg, a pianist. They fell in love immediately. They made a beautiful couple—both snappy dressers with dark hair, light skin, and large eyes, they both had a sort of formality to them that made them stand apart. Elie had moved to Paris from Romania with his mother to attend the music school; his family was poor, and his mother worked in a laundry to help pay his expenses. Though born Jewish, he was apparently initiated into the Sufi family and took on the name Azeem; their relationship was never fully accepted by the family though, and the reasons are a little unclear. Some believe that it was the difference between his Jewish background and her Muslim background; Magida mentions their class differences: his family was working class, but Noor was a princess; others say that the family didn’t like Azeem because his, quote, “overbearing behavior caused Noor emotional distress.”24

I have to wonder how much it had to do with her uncles still perhaps secretly hoping that Noor would go back to Nepal and marry Alladad. Let’s not forget that they were hoping to use that marriage to protect the family’s wealth. I haven’t seen anyone specifically mention this reason for their disapproval, but a lot of people do note that around the same time, Noor started to dress in more Western, chic fashions and that that change caused a bunch of family discord.25 The uncles once “caught” Noor and Azeem out at a café and Noor was wearing makeup and a fashionable French dress and this really rubbed them the wrong way because it was so far from what they wanted for their niece. I haven’t seen anyone outright say that her uncles disapproved of Azeem because he was, by their perception, taking Noor away from her Sufi mystic’s daughter role and making her “more Western,” but it wouldn’t surprise me if that was the case. Family dynamics are so complex, and you add a dollop of religious celebrity on top of that and they must have felt that their grasp on Inayat’s legacy would be best bolstered by their control of his children, and simultaneously, by his children living perfect typical Sufi mystic lives, whatever they believed that that looked like.

Though her family’s disapproval troubled Noor, she didn’t stay away from Azeem. They talked about getting married, and even got engaged, though Noor wouldn’t actually marry until her family approved. Her mother disapproved pretty stridently, perhaps remembering how hard life her had become after she converted and married Inayat, a man her family hadn’t approved of. Throughout the mid-1930s she walked this troubled path, trying to mediate between her family’s expectations and what her heart wanted. Her poems became melancholy again, and she often cried herself to sleep.26

I also want to note that, by some reports, Noor was doing a decent job of drawing her mother out of her depression. Pirani apparently began dressing in Western clothes again and going by her birth name, Ora; she is called many different names throughout the biographies of Noor, I’m going to keep calling her Pirani.27

Of course, we’re talking now about the mid-1930s, and the specter of fascism has risen. Noor was aware of politics, certainly—it was hard to avoid—but like a lot of people at that moment, she wasn’t paying much attention to it. As Magida writes in his biography of her, quote, “For her, the life of the spirit and the arts was the only life worth living,” and politics had little room in that.28 In fact, in her diary in 1936, Noor noted attending a performance of Rigoletto in Milan when Mussolini walked in. Quote,

Someone in the audience yelled, “Il Duce,” and the crowd went wild. “In a second,” Noor wrote, everyone in the theater “was in a fever” and the musicians almost dropped their instruments. Finally, “a profound sigh of joy rose from the whole crowd” an the opera resumed, with Mussolini “a simple spectator amongst the crowd.” Noor didn’t comment on Il Duce’s fascism, or about Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia, then in its second year, or about Mussolini’s alliance with Hitler.29

Sadness and anxiety began to creep over western Europe as war became a possibility then an inevitable threat. When war was declared on September 1, 1939, half a million Parisians immediately evacuated. Between then and the following May, Noor made two large changes: She earned a Red Cross certificate to become a nurse on the war front, and she ended her romance with Azeem, writing that she was, quote, “worn down by years of arguing with her family about him.”30

In May 1940, Noor and her brother Vilayat sat down and decided what the family would do. The local train station and several nearby factories had already been bombed by the Germans, soldiers abandoned their fort up the hill and set fire to a fuel depot to keep it out of German hands—the older children had to decide, what would the Khan family do now?

Their father had always taught them to respect all religions, creeds, and races. “Were they just words or were we going to stand up with our lives for what we pledged ourselves to?” Vilayat asked.31 But, “If you counter violence with violence, are you participating in the very violence you purport to oppose,” he always wondered.32 He looked to his older sister, his father’s spiritual inheritor in many ways, and hoped she could tell him what to do. Sufis weren’t—aren’t, I believe—strictly pacifists, but they opposed violence, and Noor didn’t want to abandon that creed. On the other hand, she saw Gandhi’s, quote, “almost willful ignorance” about conditions in Europe—he encouraged European Jews to pray for Hitler and resist his policies through nonviolence even though he knew it wouldn’t work; their sacrifice would redeem them and “score a lasting victory…” though they wouldn’t be alive to see it.33 This is a deeply troubling part of Gandhi’s legacy that is rarely talked about, but Noor was aware of it at the time and decided that he was wrong. “The essence of spirituality and mysticism is readiness to serve the person next to us,” Inayat had taught them.34 Together they decided that spirituality in action meant helping stop the Nazis.

They decided they needed to get out of France first. France was practically under siege, the French army was little match for the Nazis, and surrender seemed inevitable—and came just a few weeks later. Noor’s uncles had moved to The Hague a few years before, but the family couldn’t get there; it would have taken them, quote, “against the thick tide of the millions of people from the north who were fleeing the Nazis. And they’d be heading directly into the path of the invading German armies.”35

Noor, Vilayat, their younger sister Claire, and their mother Pirani piled into Vilayat’s sports car and began heading west to the coast of Normandy or Brittany. Their younger brother, Hidayat, drove south with his wife and infant; the family didn’t hear from him again until 1945.

Eventually they boarded a train, abandoning the sports car that wasn’t really meant for fleeing an invading army on packed and crowded roads. They took a train the rest of the way. Of the experience Noor wrote, quote,

[The train was] full of “frantic young mothers with tear-strained eyes carrying their sleepign youngsters. They knew not where [they were headed], just running toward freedom if freedom was to be found… For the little ones, France should be saved from the enemy hands at any price. I have wiped the eyes of some, given water to others… The distress of a human being is impressive, indeed, but the distress of a whole nation? Those whose hearts have not beaten and suffered with this cannot know what it means.”36

The family arrived at Le Verdon during Operation Ariel, where every available vessel that floated was being used to evacuate hundreds of thousands of soldiers to England. Unable to get a boat, they found a hotel room, but Noor didn’t stay long—she had heard about a disaster at Saint-Nazaire, a harbor town that had been strafed, including ships in the harbor. 6,000 people died in a single day, more than the combined losses of the Lusitania and the Titanic; for months, corpses floated to shore, sometimes hundreds of miles away.37 Noor arrived ready to put her Red Cross certificate to use, but the scene was too chaotic, there was no organization for volunteers or survivors yet. Unable to handle the logistics, Noor returned to Le Verdon just in time to get on a boat to cross the Channel.

They landed at Falmouth then took a train to Oxford, where Vilayat had attended university. They probably had no idea at the time, but this was the safest possible place they could have gone—invasion plans recently unearthed at the Bodeleian show that Hitler wanted to use Oxford as the capital of his new regime in England; he had strictly banned bombing it.38 It was probably the safest place in Europe.

However, once she was safe in Oxford, Noor regretted evacuating. She felt she should have remained in France and joined the partisans who were resisting the Nazis there. Her brother Vilayat enlisted in the Navy to become a minesweeper, and suddenly Noor felt the nursing was a poor calling by comparison.39 Her mother and sister worked as nurses though, her mother in a mental hospital in Oxford, her sister treating soldiers. Noor briefly worked at Fulmer Chase Maternity Home, where the pregnant wives of army officers received prenatal care and gave birth, but it wasn’t really what she dreamed of, though she probably did love the children.

She tried to enlist, but was repeatedly turned away. As a Russian citizen of Indian extraction who was raised in France, the English military probably wasn’t sure she could be trusted—even though her passport said “British Protected Person” since India was still an English colony.40 She didn’t have all the same rights as a British citizen, but she argued forcefully for her right to wear a uniform.

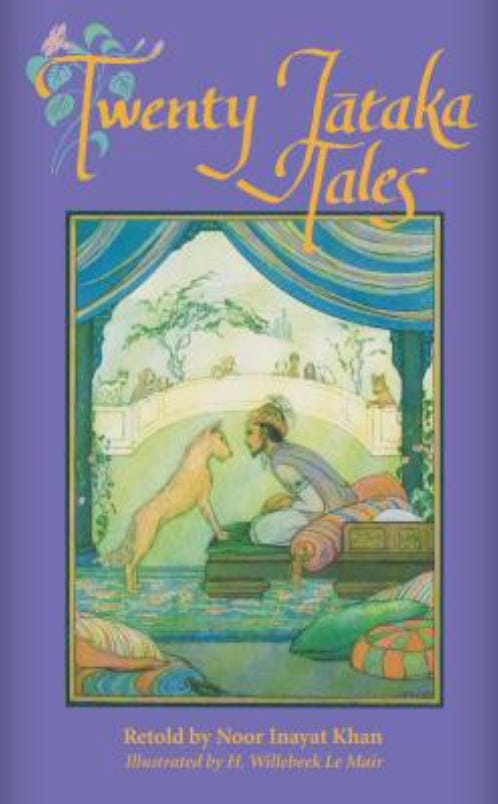

While all of that played out, Noor made friends in Oxford. She started going by Nora and was introducing herself as an aspiring writer; in fact, she was already a published author. She had been writing children’s stories in English and French and submitting them to magazines, she’d also contributed to story radio broadcasts.41 In 1939, her first book Twenty Jātaka Tales, a collection of stories about the incarnations of Buddha, had been published by G.G. Harrap & Co. in London. The book is still in print!

Her new friends found her quiet but impressive. The gentleness of her voice was noted as, quote, “the thinnest little pipe…such a voice as creatures of fairyland might be expected to use.”42 For Noor, who had always loved fairies, this was probably a lovely compliment.

Finally, on November 19, 1940, Noor enlisted in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. The WAAF primarily eavesdropped on German radio messages and studied radar screens, telling British pilots where the Luftwaffe was flying over England. She went through basic training, including a stint in Edinburgh for advanced training on wireless telegraphy. Edinburgh was bombed eighteen times during the war—twice during the winter that Noor was there.

After training, Noor was interviewed by a board that would decide where she would be commissioned. The fact that she was Indian became a matter of serious consideration—there were many Indian nationalists who didn’t want Indians fighting their colonizer’s war, there were racist British people who didn’t want Indians to join the British military, there were also British people who were racist enough to want the Indian people to die fighting instead of white British soldiers. It was a testy issue. And Noor got into an argument with her interviewers over it. She supported India’s independence and when asked, quote, “If Indian leaders take measures embarrassing to Britain, will you support them?” She responded, “My duty is to support the measures of any responsible Indian leader.”43

“Is that inconsistent with your oath to the Crown?” They asked.44

Noor conceded that everyone was equally in danger from the Nazis—as long as Hitler was in power, she was loyal to Britain. She was sure this was the wrong answer, and felt sure she’d be dismissed from the military, but weeks later, she was invited to London for a meeting. On November 10, 1942, at promptly 4 pm, she arrived at Hotel Victoria, where a new agency, one completely secret to the British public, had requisitioned room 238: The Strategic Operations Executive.

Winston Churchill himself had created the secret branch, determined to use it to spread “fear and chaos among the Germans who were occupying Europe.”45 He had plans for your classic covert resistance moves—hinder transportation, cut telephone and telegraph wires, send intelligence to London, and kill German soldiers if the opportunity arose. He didn’t want spies, exactly—quote, “By making a ruckus…Churchill’s new agents would give Nazis the military equivalent of a nervous breakdown. Until England was strong enough to fight the Nazis head on, sabotage was the game.”46 It was so secret that most agents in the agency didn’t even know the name of it; Churchill privately called it the Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare.47

After the interview, Noor’s file was passed to the SOE because of her skill with languages. By the time she arrived at the Hotel Victoria, the agency’s past, such as it was, was littered with impressive successes and miserable failures. Captured agents had been forced to ask London for weapons and more agents, all of which were immediately captured by the Nazi war machine. But they’d also interrupted supply lines to Rommel in North Africa and destroyed a plant where Nazi scientists were trying to create heavy water for an atom bomb. Of course, she knew none of this.

She was interviewed by Selwyn Jepson, author of a dozen detective novels like Keep Murder Quiet. He had fought to meet with Noor because he had a feeling she would be perfect for the role—in fact, he tended to believe that women were “better than men”’ for the SOE anyway because they had a, quote, “cool and lonely courage” that men didn’t because they’d never been trained to work alone.48 His books are mostly out of print today, but there was another man floating around the SOE whose books you can still find—Ian Fleming, author of the famous James Bond novels. It doesn’t seem like Fleming ever met Noor, but she might have heard about his ideas for sabotaging the German military.

In any case, Jepson was instantly sure that Noor would make an invaluable asset as a wireless operator—she spoke perfect French and fit in in Parisian society, two of the things he was most concerned with. She also was quite beautiful and had a very elegant bearing, which Jepson found to be really important in undercover work, especially against the Nazis. He believed that, quote, “good looks and a refined personality made agents seem like they were part of the moneyed, leisure class. Germans didn’t like stopping someone like that—even Nazis were intimidated by the rich.”49

Still, Jepson encouraged Noor to really consider whether going back to Paris undercover was right for her. Most wireless operators didn’t survive more than six weeks in Europe because the Nazis knew how invaluable they were—the whole resistance fell apart if they couldn’t communicate with one another. If she went, she would undoubtedly be targeted, and if caught would face horrifying torture before certain death. He also encouraged her to consider her dreams as a writer, saying, quote, “You could be justified thinking you can be more valuable to humanity by surviving the war and using your skills as a children’s author to help shape the minds of the youngsters who would be inheriting a partially destroyed world.”50

Noor thought about it and accepted his offer to join the SOE the next day. She signed the Official Secrets Act and began wearing the uniform of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, which was often used as a cover for women in the SOE. Her training at Wanborough Manor, in Surrey, was a, quote, “crash course in ingenuity and self-preservation.”51 She already knew how to operate her radio, now she needed to learn the practicalities of surveillance, how to escape into a crowd, and how to kill quietly and efficiently. They played games designed to sharpen their observational skills, and then the men were tested with liquor and beautiful women—the female agents were not tested the same way. One thing they also learned was how to identify and encourage, quote, “local women with venereal disease to have sex with Germans as a way to infect the enemy.”52 I guess this is where that saying “all is fair in love and war” comes in, huh?

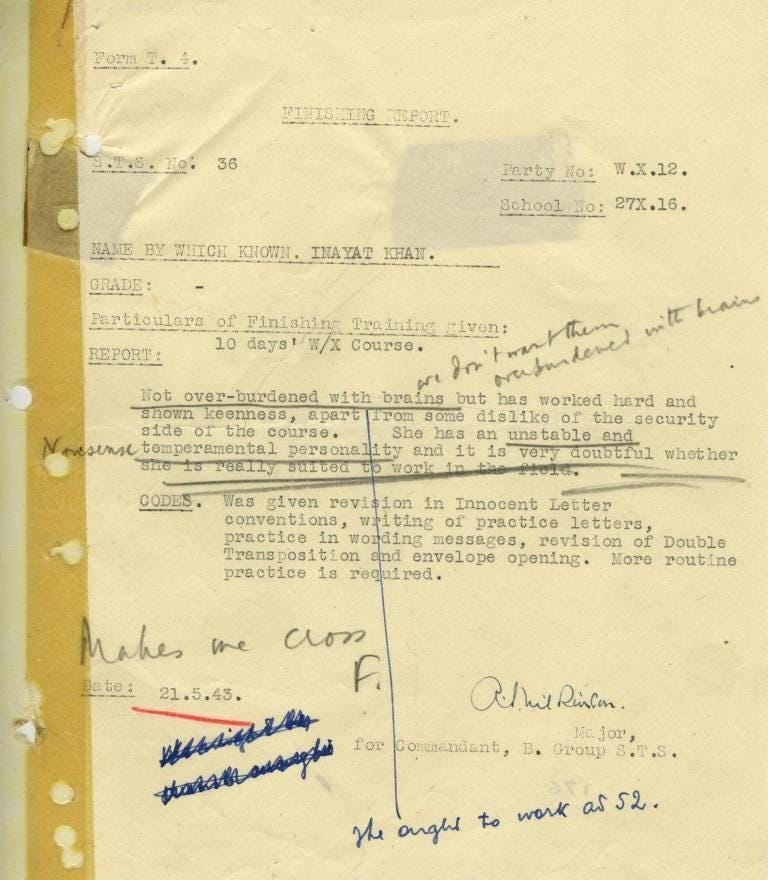

Although Jepson had been sure that Noor was perfect for this work, her trainers were not so convinced. Noor was tall and thin, apparently awkward and clumsy when doing anything other than playing a musical instrument; she struggled with map reading and was too literary to get the hang of writing reports quickly.53 Also, she had a surplus of integrity, which sounds like a good thing but meant that, in practice, she hated to lie—not a great quality for an undercover agent. Still, she grew in confidence and passed to the second phase of her training, where she studied codes more sophisticated than the ones she’d learned in Edinburgh. She also learned how to operate a portable wireless device that was small enough to fit inside a suitcase—while on the ground in France, she would need to be able to set it up to send and receive transmissions all by herself, there would be no one there to help her with maintenance, so she learned all of that.

The SOE called the radio operators “pianists” because the operator’s cadence of transmission eventually developed a cadence that was identifiably their own, sort of like a musician’s signature.54 They called this cadence an agent’s “fist” and once established it tended to remain the same, no matter how tense a moment was; agents could often be identified by their fist alone, and experts used their fist to confirm that the messages had truly come from an agent, not an enemy imposter.55 As a longtime musician, Noor found all of this extremely easy.

Her third stage of training was a new one to the SOE. Initially, the SOE had thought that radio transmitters didn’t need security training, because they would be protected by the rest of their cell. But it quickly became apparent that a compromised radio operator was a danger to an entire cell; they established a “finishing school” for security at Beaulieu, a beautiful estate near the woods.56 There, Noor learned how to mix invisible ink, how to lose a tail, how to disguise her appearance, and how to endure an interrogation—sans breaking bones and actual torture.

As a final test, Noor was sent to Bristol with a mission: recruit contacts, scout around for places to send or receive messages, get a flat that’s safe for her wireless, and endure another fake interrogation. Her results were a mixed bag—she did well with the flat, the dead drop, the contacts, but she did not stand up well to the interrogation. And, worse, when she was biking around town with her radio, a policeman stopped her to ask what she was doing and she said, “I’m training to be an agent,” and offered to show him her radio!57 That’s not secret! What a wild thing to do! Noor had always hated lying, and this was proof that the SOE’s concerns about her integrity were valid. Thankfully, this answer was so brazen and ridiculous that when the officer reported the suspicious incident to the SOE, he said, “If this girl’s an agent, I’m Winston Churchill.”58

In between her training and missions, Noor had time for a social life. She briefly dated an RAF airman, but when he mentioned that she reminded him of an ex, she intuited that they were still pining for each other and she single-handedly got them back together; they married soon after.59 She started dating another officer and planned to marry after the war; unfortunately, we don’t even know his name because Noor never told anyone in her family who he was; perhaps she was wary that they would interfere as they had with Azeem—apparently he was not Muslim either.

At some point, she became blue and despondent. Her fellow agents were so worried they wrote to Vera Atkins, one of the top advisors to Maurice Buckman, who oversaw the SOE. She was in charge of all his French agents, so Noor was under her purview. She summoned Noor to London, relaying her agents doubts to Noor. Quote, “Atkins needed to hear that Noor hadn’t lost confidence in herself and to assure Noor that she could back out of her mission gracefully” if she needed to.60

Noor’s concern was soon revealed: Lying to her mother. She wasn’t worried about her mission, about the danger in France. She had just never forgotten her father’s rule to honor her mother above even her prayers.

Moved, Atkins asked how the SOE could support Noor. Noor requested that they bend their rules for Pirani—instead of promptly informing the family when an agent went missing, which was SOE policy, Noor asked them to lie for her, to only tell her mother anything at all was wrong if and when Noor was confirmed dead.61 Atkins agreed.

But soon enough Noor didn’t have time for dating or worries. In June 1943, Noor met with Leo Marks, the SOE’s codemaster. He met with every agent for an hour before they were sent out, but Atkins’ boss, Buckmaster, had heard about concerns regarding Noor and asked Leo Marks to meet with her for longer. He scheduled her for a three-hour meeting—”Any longer than that, and I might emerge as an Indian mystic” he later reflected.62 He studied her background extensively, even buying her book Twenty Jātaka Tales to get to know her better; his reaction was one of despair. “Oh Noor, what the hell are you doing in the SOE?” He wondered.63 She was sensitive, spiritual, and artistic—Selwyn Jepson and Maurice Buckman might have been convinced that she could overcome a lifetime of gentle spirituality, but Leo Marks saw what her trainers had been worried about: Noor’s temperament, on paper, was not quite right for undercover work as they envisioned it.

When Noor arrived at the flat on Baker Street that Leo used for these final briefings, they worked together for hours on codes. Having read her book, he reframed the necessity of lying for her in a way that made it less unbearable. They negotiated how she would respond if the Nazis caught her—utter silence meant she wouldn’t have to lie or risk the SOE. But the meeting didn’t change his mind. He still didn’t want her to go to France, so he set what he thought was an impossible final final test: encoding three long messages with her security checks by noon the next day. She returned to the flat the next morning with six such messages, and they were perfect. She was cleared for her assignment.

At around 10 pm on June 16, Noor boarded a Lysander plane flown by a 23-year-old pilot named Frank Rymill. He had already flown 65 secret flights in ten months and he never lost a single agent.64 The flight was precarious—in addition to regular concerns like bad weather, they had to worry about German aircraft. And though they of course hoped to be met with allies when they landed, they might have been met with Nazis if any details about the flight had been leaked. For this reason, she flew without her radio—it was best to have as little incriminating materials on one as possible, just in case. It would be parachuted to her later.

Their flight was safe though. Rymill landed near Angers early the next morning, and Noor was given a bicycle and new names: Madeleine to anyone in the Resistance, and Jeanne Marie Regnier to Germans and ordinary citizens. Noor, called Madeleine, rode her bike to the village of Ettriche and boarded a train to Paris to meet her contacts—her mission was to help a cell named Cinema being established southwest of Paris.65 Under no circumstances was she allowed to contact friends, family, or teachers still living in Paris—no one who knew her real name. She would send messages to London at set times and days and receive messages on different ones. Not having immediate back and forth conversations made it harder for Nazis to track radio signals—which they could do with tiny detectors embedded in watched, as well as fake ambulances that they drove around streets, searching for illegal radios.

Though this was her mission, she had dozens of orders that covered any number of possibilities: Ones for if she couldn’t find her Resistance contact, if the radio didn’t work, if she needed to escape. There were safe houses in Spain and neutral addresses in Portugal where she could get messages, and intricate combinations of passcodes and safety measured designed to protect her. Even with all of this preparation, the SOE still only thought she’d last six weeks.

But they were right to worry—they had no idea, when Noor landed in France that just the week before one of the Resistance members that was part of her reception committee had been turned and was feeding information about the SOE to the Nazis. Some of the SOE’s best agents in France had been caught in the weeks preceeding her arrival, and the country’s best information network, called Prosper, was toppled in the first weeks that she was in France. The network had once included nearly a thousand English agents and French résistants—they had wrecked factories, derailed trains, grounded power stations. Now they were gone. By July, Noor was the only radio operator the SOE had there.

Two weeks later, when Noor could finally pass the news to England that Prosper was gone, she was immediately ordered home by Maurice Buckmaster. She refused, saying she could stay for at least a month to help rebuild Prosper. Buckmaster wanted to say no, but they needed a radio operator there in order to rebuild the network, and she was already on the ground, ready to go. She was catapulted into the most dangerous position an English agent could occupy in France: An agent alone, without a network to protect her.

Noor was constantly on the move. She cycled almost everywhere around the city—all cars had been requistioned by the Gestapo—retrieving messages from dropboxes or meeting the agents left in Paris. We don’t know what she did every day, but we know she moved safehouses frequently. She also carried her radio around with her—she didn’t want to risk it being found if the Gestapo raided her apartment because then it could be used to impersonate her.66

Of course, this carried with it its own risk: Once on the Métro, two German soldiers approached her, looking at her suitcase. Riding between stations, she couldn’t simply slip away, so she was a sitting duck when a soldier asked her what was in the case. She claimed it was a film projector, but then he wanted to see. She raised the lid slightly, and when the Germans peeked in, she realized they couldn’t have identified what it was anyway. “Well you can see what it is,” she snapped at them. She pointed at the tubes and said, “You can see all the little bulbs.”67 They left her alone.

She was approached by other German soldiers about her case at least one other time. She came up with a better lie, saying that her case contained a portable x-ray machine; the soldier didn’t dare ask her to open it.68 Either the SOE prepped them with lies—maybe even Leo Marks had, in their three-hour meeting—but Noor proved to be more adept at lying than perhaps even she was comfortable with.

Her greater stressor was trying to find somewhere to extend the antenna for her radio—it was nearly seventy-feet long, and it required a yard, or a tree, or a balcony with a rain gutter—something.69 And since she kept having to change safehouses, she kept having to find new places to put the antenna. Eventually, a couple of résistants brokered a deal with her, they would risk driving her to a different part of the countryside outside Paris a few times a week so she could transmit messages, if she would also transmit messages for them since they had lost their radio operator—she quickly agreed.70 Away from the city, it was much safer, but they weren’t always available at the set times she was supposed to report in, and it was dangerous to be seen with the same people too often in case one was being watched, so she still needed to find other safe locations to transmit.

Finally, Noor broke the first big rule of the SOE: She contacted an old teacher. She contacted an elderly harp teacher who she had briefly studied with, Henriette Renié, who she knew hated the Nazis and loved Noor. She had hoped that Henriette would know of a place Noor could rent that would be suitable for the radio—she even openly told her what she needed and why—but the woman didn’t.71 Nevertheless, it broke the seal on the no-contact rule.

To be fair, it wasn’t entirely her fault—a lot of people didn’t get out of Paris. Either because they couldn’t, or because they were part of the resistance, or because they sided with the Nazis—and so she was also recognized by people from her former life. She hadn’t been gone that long, and though she had dyed and cut her hair, and was altering her appearance with various tricks that the SOE had taught her, it wouldn’t be enough for people who had known her nearly her whole life.

Plus, Noor wasn’t the only agent breaking these rules. The best agent the SOE had in France, Frank Suttill, had basically immediately contacted a childhood friend, Nicholas Laurent, when he arrived in France in 1942—these agents needed trusted allies and secure locations, and who better to provide that then locals they’d spent their whole lives vetting?72 I understand why the SOE set the rule, but I also understand why it was frequently broken.

So Noor next contacted her childhood physician, Dr. Jourdan, who offered her use of his country home in Marly-le-Roi so she could transmit messages.73 It was perfect, but of course if she was caught there, it would bring trouble to this family that had been so good to hers, so she was hesitant to go there too often.

Eventually, probably lonely, stressed, and scared, Noor contacted her childhood best friend: Raymonde Prenat. The family had remained in Suresnes, and Noor began to visit them again, seeking the comfort of people who loved her. They understood that the work she did was dangerous and wisely asked her nothing about it, supporting her however they could, which was often with a warm meal and a trusted confidence.

Noor probably had no idea how dangerous it was to be in Suresnes, but she soon learned. The Nazis had occupied the suburb, taking over her very neighborhood first.74 The Gestapo had taken the fort nearby her childhood home, and they executed prisoners there regularly, the gunshots muffled by trees and slight dips in the mountain.75 Her own home, Fazal Manzil, had been turned into a station for the German police and twenty-eight officers were living inside.76

Finally, another SOE agent found Noor an apartment that she could sublet in Paris. The previous tenant was leaving the city, and leaving her furniture and her boyfriend behind, providing Noor with not only a perfect base of operations but also a perfect cover: The boyfriend kept coming over to make everyone think he was Noor’s boyfriend.77

The only problem was that, well, the building was occupied primarily by Nazis. The SS occupied almost every other apartment in the building, and Noor brushed shoulders with these men in the hallway. One day, Noor needed to send a message to London immediately so she decided to take the risk of transmitting from her apartment. As she was trying to hang the antenna from the branches of a tree outside her building, an SS officer approached her. He offered to help her, and she simply handed him the antenna, which he hung for her. He finished the task, bowed to her, and left.78

Later, she told the story to Raymonde, who was incredulous. No one was allowed to have a wireless in Paris at the time. But of course people did, listening to music and radio broadcasts illegally; Noor guessed that the soldier had assumed that that’s all she was doing and decided to look the other way, at least for the time.79

The soldier wasn’t the only one in the building who had noticed Noor though. The concierge of the building, Madame Jourdois, had also noticed that Noor seemed to have an endless supply of English men visiting her and leaving her letters or packages.80 Monsieur Jourdois had also noticed this and advised his wife to pretend she saw nothing and heard nothing: He recognized an Allied undercover agent when he saw one, and he knew that the best way to keep Noor safe was to pretend she didn’t exist.81

And good thing he did. Noor was solely responsible for getting new agents into France as well as getting compromised ones out. She helped arrange rescues for downed pilots and sent coordinates for weapons drops for the French resistance. This at a time when homegrown French resistance was starting to splinter under the strain of war and ego and contrary visions of a post-war France.82

It was now mid-July 1943. Noor had made several contacts around Paris, including a businessman who the Nazis were convinced was on their side, but was actually introducing agents to French politicians to work together to plan for the future of France after the Nazis were defeated; Noor met several politicians this way, though we don’t know much about those conversations.

She also arranged for the arrival of spymaster savant Nicolas Bodington, who managed to work for the SOE and MI6—the two agencies were rivals, and rather than work together they often got in each other’s ways. It was dangerous for Bodington to enter France though—if he was caught, he knew all the secrets of both agencies.

Together, they began laying the groundwork for a new cell. Bodington bought a café, Chez Tutelle on Rue Saint-André des Arts, quote, “to use as a contact point for SOE agents, escaped POWs, and downed pilots, or as a dropbox for agents who wanted to get messages out of France or to other agents who were there. With five exists, including one underground, and a room that could double as a bedroom in an emergency…the Tutelle was ideal. Even the possible drawback—it was near the Nazis’ headquarters—was an advantage. Some agents preferred working near the enemy, the least-expected place for them.”83

It wasn’t meant to be a gathering place, of course—people would start to notice if a bunch of British agents were just chilling at the same café every day. But agents could go to arrange a flight out of Paris. Under normal circumstances, the café would have closed in months—it didn’t do much in the way of restaurant business. It did however, “help many spies, agents, and soldiers get out of France.”84

When Bodington got ready to leave Paris again in August 1943, he tried to get Noor to leave with him. She had already exceeded the life expectancy of radio operators and had had way too may close calls for anyone’s comfort. But she refused, and they decided not to force her; they could have ordered her back to England, but they let her stay if she felt like she could do it. The situation was no longer as desperate as it had been before—she had arranged for the arrival of several other SOE agents during her time in France already—but there still wasn’t another radio operator to replace her.85

Then, just three days later, Britain evacuated ten more agents from northern France. Noor arranged their flights, but stubbornly remained in Paris, now the only SOE agent left in half of France.86 She was almost entirely alone.

Soon after, the Gestapo learned of an agent named Madeleine. They raided an estate, and among the general family’s belongings were some notes from radio transmissions Noor had made, signed Madeleine.87 She should have destroyed them, and when she didn’t the family should have, but now they were in the hands of the Gestapo. They knew through double-agents that the SOE was running out of operators in northern France; they correctly guessed that this Madeleine was a key figure to the British, and set about trying to find her.

They had no idea that she was living shoulder-to-shoulder with SS officers, that one had once helped her set up her radio. They had no idea that she was visiting her former neighbor, Madame Pinchon, who still lived next door to Fazal Manzil, the German police station. Nor did they know that she had begun using Madame Prenat’s home, who lived up the street from Fazal Manzil, to transmit messages because her own apartment didn’t have the space.88

Raymonde Prenat was still there, of course, as I’ve mentioned before. Noor allowed Raymonde to watch as Noor sent messages, and eventually taught Raymonde the code and asked for her help deciphering messages; her biographer compared it to how they used to do schoolwork together.89 He doesn’t say this, but part of me wonders if Noor was—recklessly—hoping to train another radio operator in case something happened to her. Despite the heavy enemy presence, Noor felt safe in Suresnes, though she was careful to ensure that she was never followed coming or going.

That said, it was clear to her handlers, like Vera Atkins, that Noor was getting tired. She never spent more than four nights in the same place, often moving around to avoid detection, though she kept her apartment. She lugged the 30-pound radio everywhere. She didn’t get enough sleep, and the rations meant she wasn’t eating enough either. Noor started to get sloppy—she sent an unciphered note to London once, asking for more crystals for her radio and to move her messaging time slot.90 This was a huge breach in protocol—had any of the intermediaries between her and the pilot been caught with it, it could have brought down several people.

But the German net closed around her tighter not because of any mistake she made—instead, another agent had been caught and confessed enough information that allowed the Germans intercept a message that was sent to “Madeleine” on August 15th: She was to meet Frank Pickersgill and John Macalister, a couple of Canadian agents, in the basement of a café and put them in touch with Maurice Despret, the head of a group of anti-German industrialists.91

Unbeknownst to Noor or to her British handlers, the two Canadian agents had been captured a few weeks before. When Noor arrived at the café, it was two SS officers she was meeting: Karl Horst Haldorf and Josef Placke.92 They sat down and had a conversation with her, memorizing her face, voice, and gestures—but they didn’t arrest her. “Madeleine” was their new key to taking down more of the resistance.

Bizarrely, no one followed Noor after the meeting, a colossal failure of even the most basic spycraft—why she wasn’t followed has been debated for decades.93

The next day, the “Canadians” met Noor at a different café, and she took them to meet Despret. They had brought their own radio, taken off the real Canadians when they were arrested, and began arranging for drops of weapons, money, and agents. These falsified drops went on for ten months, allowing the Gestapo to nab 300 containers of weapons, 2 million francs that the SOE intended for the French Resistance, and 6 SOE agents who were dropped directly into Nazi hands.94

Now that the Nazis were working directly with Despret, they didn’t need Noor anymore, but they still didn’t arrest her. She sent good, actionable information to the British, including the fact that Paris’s southern airport, Orly, had been transformed into a Luftwaffe base; the Allies bombed Orly as D-Day got closer, based on Noor’s message.95 She knew which factories were secretly collaborating with the Nazis—BMW, Renault—and the RAF bombed them too.96 Thanks to her transmissions, the Allies were able to target strategic sites, ensuring that D-Day would be a success.

Soon, Noor moved to the fashionable sixteenth arrondissement, a neighborhood for the moneyed of Paris. Her new apartment was blessedly free of SS officers and was large enough to spread out her antenna in it. She soon began working with Pierre Viennot, an executive at the French telecommunications company SFR. The company had been brought under German control, but many of the employees were deliberately sabotaging products—they were, quote,

“drilling holes with the wrong diameter, screwing nuts in the wrong way, calibrating lamps for the wrong wattage, writing manuals so whoever relied on them would damage the equipment they were using. Some SFR employees hid Jews in back rooms of the company’s factories; others used the same equipment with which they printed labels and handbooks Mondays through Saturdays to create fake identity cards and passports on Sundays.”97

Viennot had tried to keep his head down during the intial part of the German occupation, protecting his young family, but had been radicalized by his 18-month old son asking if the Nazi flag flying over the Senat was the French flag; he began actively resisting the Nazi occupation by doing whatever he could get away with while maintaining his important place as an executive within a German-controlled company.98 He stole German seals and used them to “authenticate” fake identity papers, helped kill a German officer, stole blueprints for Nazi radio jammers and passed them to the SOE, and his position in the telecommunications world meant he had access to all sorts of information about Nazi technology; he helped the SOE take down German floating radio stations that they used to guide their submarines, for instance.99

Viennot was only a few years older than Noor, but he became something of a guardian to her, allowing her to use his flat to send messages and sometimes guarding her while she slept. He fixed her radio when it needed work and paid for her to buy new clothes and get a proper haircut and style to disguise herself again when her flat became compromised after another agent she’d worked closely with was caught.100 In fact, her apartment was raided by the Gestapo just 24 hours after she abandoned it. Viennot also begged her to get rid of notebook that she carried with her everywhere—it contained every message she had ever ciphered and deciphered! It was wildly dangerous for her to have it, and went against everything the SOE had taught her.

The Gestapo was finally closing in. Everyone urged her to leave Paris, and finally she agreed to. It had been four months, and she had survived more than twice as long as predicted. During the first week of October, she arranged her own flight out, though she knew it was risky if her radio had been compromised as well. She also arranged to go with Viennot’s secretary, a resistant named Simone Truffit, for one last mission to blow up a shed full of Metoxes—”small gadgets that warned Nazi subs if they’d been found by Allied radar.”101 She never showed up, nor did she show up for her arranged flight.

In the end it was the prettiest of betrayals that got Noor caught, and it makes me livid just to think about it. On October 7th or 8th, a woman named Renée Garry called the Gestapo: She would give them everything about Madeleine, including her address, if they gave her a hundred thousand francs.102 The thing is, Renée had no idea how important Noor was. She had no idea that the Gestapo would have paid ten times more than her offer, and even if she did she probably wouldn’t have cared, because for Renée this wasn’t about the war.

See, Renée was the sister of Emile Garry, Noor’s handler when she first arrived in France. Renée was sort of tangentially aware of Resistance efforts, but wasn’t involved—but she knew who “Madeleine” was because this new woman had caught the eye of someone Renée was interested in. There’s no evidence that Noor and this unknown man dated, but Renée was jealous, and she wanted “Madeleine” out of the picture, so her crush would focus on her. So she reported Madeleine to the Gestapo.

Just absolutely unhinged behavior. If she’d just asked her brother, Emile probably could have found out that “Madeleine” was going home soon, which would have accomplished the same goal for Renée without getting anyone brutally tortured and killed. After everything Noor had done to stay ahead of the Nazis, for this to be the reason that she got caught, keeps me awake at night.

But sure enough, it was. Renée led them to Madeleine’s new apartment in the sixteenth, showing them where she kept a spare key.103 On October 13th, 1943, a man named Pierre Cartaud let himself into Noor’s apartment and hid, waiting for her to return. He was a turncoat, once a member of the French Resistance who had been caught and turned. He was so intent on his new identity that he insisted on being called Peter; even the Nazis didn’t trust him or like him.104 Cartaud caught and turned over as many as sixty French Resistance members to the Nazis.105

When Noor returned to her apartment, Cartaud grabbed her. They fought violently, but Cartaud pulled a gun; Noor wasn’t armed. He called headquarters, and she was arrested; they took her radio too, as well as her notebook full of her decoded messages. They would use it to mimic her fist, as the British called it, and get as much out of the British SOE as they could.

She was taken to 84 Avenue Foch, where prisoners were interrogated and often tortured. But it was also probably the nicest German prison in existence at the time—she had a bed, blankets, and access to a small library stocked with detective novels.106 On Sundays, the head of the prison would personally distribute pastries, chocolates, and cigarettes to prisoners—though they were ready for torture, “friendly persuasion” was the preferred method at no. 84.107

In charge of this was a man named Ernest Vogt—he was “cosmopolitan,” educated, and spoke several languages; he’d been sent to no. 84 as an interpreter. He wasn’t even technically a member of the Nazi party.108 Instead of scary and violent interrogations, Vogt invited prisoners to tea, catching them off-guard with his urbane manners and civilian dress. He felt that this was a particularly useful way to get information from English prisoners, who put a high premium on good manners and civil behavior.

When he first met Noor, she burst out at him, quote, “You now who I am and you know what I have been doing. You have my radio. I will tell you nothing. I have only one thing to ask of you: Shoot me as quickly as possible.”109 After an hour with her, Vogt gave up—she was too stubborn and keyed up from her arrest. He said she could go to her new cell to calm down, but she asked to bathe first in the private bathroom available to prisoners on the fifth floor. He agreed but was slightly suspicious—he went to the room next to the private bathroom and looked out the window. Sure enough, Noor had already climbed out the window in the bathroom and was balancing on the rain gutter, which trembled beneath her; she risked falling six stories to her death. (In France, the ground floor is floor zero, and the one above it is the first floor; so 5th floor would be six stories high by the American way of labelling floors.) Vogt talked her down, convincing her to grasp his hand and come back inside; she did, but immediately collapsed in tears, calling herself a coward for not choosing death over capture.110

For weeks, Vogt met with Noor every day, sometimes for hours. She held her ground and gave him nothing. Bound by her promise to Leo Marks to say nothing if captured, Noor really did say nothing, not even her other fake identity—they still only knew her as Madeleine. When they talked, it was about art or poetry; she asked for paper to write children’s stories and told Vogt she missed her mother. Later, after the war, Vogt admitted that in another world, he would have liked to be Noor’s friend, a fact he proved when he started to get close enough to possibly get information from her then suddenly warned her off, reminding her that he was her enemy.111 His method was often effective, but it could just as easily be a source of weakness for him.

Meanwhile, Noor had begun to befriend two other prisoners at no. 84: Léon Faye and John Starr. Faye was known as the escape artist of the Resistance; by the time Noor met him, he had already slipped out of two other German prisons.112 Starr, on the other hand, was so friendly with his captors that, quote, “charges of collaboration would hound him for the rest of his life,” and it seems like people still aren’t really sure where his loyalties really were.113 The Gestapo took him out to dinner, he helped them with their fake messages to England, and he frequently encouraged other prisoners to cooperate.114 But when Faye and Noor began planning an escape, Starr was on board, offering to help by gathering supplies like a rope, tools, et cetera.

They decided to go though the skylights—their cells were on the top floor of the building, in the mansion’s old maids’ quarters. On November 24th, they made their move, scraping away plaster and bars that they’d been working on for weeks to climb through the skylight. Faye got out first, around 10:30 pm, and began scouting their escape, realizing quickly that Starr’s information about the surrounding streets and layout of the buildings was dead wrong.115 This might seem like betrayal, but Starr was also covering their escape with loud music, and had been scraping away at the bars covering his skylight this whole time as well. Starr had also collected every map he could steal and piece of information he could think of about the Germans to take with him to England—he intended to be a hero upon his return. Truly, it’s hard to say who Starr was loyal to.

Meanwhile, Noor was having trouble freeing the last bar from her skylight. With the help of Starr and Faye, she finally got out around 3:30 am. Now, things could have gone well from here—except an air raid siren went off. Standard procedure inside no. 84 was to check on the prisoners to make sure that they weren’t signalling to bombers flying overhead. They realized that their cells were empty, and soldiers “poured onto the streets and onto the roof.”116 They managed to escape notice at first, but German surveillance became even more diligent.

The three managed to break into the apartment building next door, went downstairs, and tried to make a run for it; Faye went first and was instantly caught.117 Noor and Starr broke into an apartment and hoped to wait there for a few hours, but the woman who lived there woke up and began screaming; the Gestapo heard and swarmed the apartment, arresting them.118 Starr, Noor, and Faye were all back in their cells before sunrise; Starr cut some kind of deal, but Noor and Faye were on a train to Germany within 24 hours.119

Faye was sent to Bruchsal, where he was sentenced to death by a military court the following June. His sentence was not carried out, however, until January 30, 1945. He was survived by his fiancée, Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, head of the resistance group Alliance, and their infant son.

Noor was sent to Pforzheim, with the warning that she was, quote, “An important terrorist, an expert escapist.”120 She was the first British agent imprisoned in Germany, and one of the few locked up under Hitler’s “Night and Fog decree.”121 She was kept in handcuffs, which were attached to leg irons, at all times. Her cell, cell #1, was tiny and dirty, infested with bugs. She was never let out of it. She turned 30 there on January 1, 1944.

But there were a few other French women in cell #12, and they managed to contact Noor by scratching correspondence onto the bottom of the tins that their food was served on. Noor had no idea that they were members of Alliance as well, the resistance group Léon Faye had been a member of. They passed Noor messages by whispering them as they passed her cell or scratching them on tins. When D-Day occurred on June 6, 1944, they sang loudly about the invasion so Noor would know. Though she knew that D-Day went well, she had no idea how much her messages had helped; since her capture in October, the Allies had kept acting on her intelligence, destroying key German strategic avantanges that ensured the Allied landing was a success.

In Britain, Noor’s mother had not yet been alerted that anything was wrong. In fact, it took the British several months to confirm that Noor had been arrested; as late as April 1944, they were still trusting her messages. The result was several agents caught by the Gestapo, as well as money and weapons. Clearly, if Emile Garry had found out about his sister’s betrayal of “Madeleine,” he’d said nothing. However, there were occasional reports from others that Noor had been arrested as early as October 1943; Leo Marks also thought that the new messages coming from her after that were wrong—they were missing her security checks; but Maurice Buckmaster was convinced she was still safe and fine.122 He recommended her for a George Cross, a medal for exceptional heroism established by King George VI, while Noor was already at Pforzheim.123

As the German military began losing control of France in the summer of 1944, they had no more need for the SOE agents they had been holding prisoner. Between June and September, they killed 91 agents.124 On September 11, Noor was transferred to a prison at Karlsruhe, where she ran into three other female SOE agents, including one that she had trained with. Their names were Yolande Beekman, Madeleine Damerment, and Eliane Plewman; Noor had trained with Yolande at Wanborough in 1943.125 The women were transferred together first to Stuttgart then on to Munich; their ultimate destination was Dachau. They arrived there around 11:30 pm on September 12th.

What happened from this moment is a matter of some debate. Various German soldiers have told different stories, blaming various people; but no one has ever taken credit for the murders that happened next. The most repeated account says that on the morning of September 13th, 1944, around 9 am, the women were led out to a small mound of earth and read their death sentences. Yolande apparently asked for a priest, but was denied one. They were told to kneel down, facing the mound. They held hands as they were each shot in the back of the head, dying instantly. Their bodies were cremated.

Other accounts differ in the level of violence the women endured. Some say that they were all stripped and beaten, some say only Noor was. Some say they were killed upon arrival at Dachau, others say the women got a full night’s sleep and were executed in the morning. Some say they were shot, others say they were beaten to death; one claims that Noor was thrown into oven for cremation while still alive. In some accounts, Noor is given a last word: Liberté, but in others, well, if she said anything no one bothered to record it.

This is one of those moments when I don’t really know what to believe. The depravity and desperation the Nazis had sunk to by this point in 1944 makes it seem like the almost peaceful execution in the morning is too…nice. But the other stories of stripping and beating, which are graphic in a way that suggests sexual violence, also seem sensationalist to me, told by bitter losers who just wanted to get a rise out of their interrogators after the war. And then there’s the added dimension of the stereotypes of the female spy, the sexually promiscuous and morally bankrupt woman who is finally revenged upon by being beaten and humiliated while naked at her enemy’s feet. It’s gross. I mean, everything about the what the Nazis were doing was gross and horrifying, but that’s also why I don’t fully trust any of their accounts of the last hours of Noor’s life. And ultimately, it’s impossible to know what’s true since her body probably were cremated and can’t be examined for signs of injury.

In any case, Noor Inayat Khan was killed at Dachau on September 13th, 1944. On September 29th, a couple of weeks after her death, the SOE was still sending Pirani positive letters about Noor’s status, lying on her behalf as she had asked them to. It wasn’t until October 15, 1944, after the SOE had heard more information from other liberated agents, that her family was notified that the SOE had lost contact with Noor and considered her to be a prisoner of war.126

Her sister Claire and her brothers Vilayat and Hidayat survived the war. Vilayat and his crew had helped clear the Channel of explosives in time for D-Day; he often had to defuse the bombs himself.127 Once he was relieved of duty, he badgered everyone he could get in touch with for news about Noor; finally in July 1945 he had a dream that she was telling him, “I’m free.”128 His friend interpreted the dream as Noor telling him she had been freed from a camp and would be coming home; he interpreted it as she was dead.129 The British government finally confirmed in 1946, though they still didn’t have any hard facts; it just seemed impossible that she wouldn’t have turned up yet if she was still alive. Her mother, however, never learned over Noor’s death; she’d become fragile during the war, and Noor’s siblings hid the truth from her. She passed on May 1, 1949, still not knowing the truth.

That same year, Vilayat attended the trial of Renée Garry, the woman who had betrayed Noor to the Nazis; he found it difficult to forgive her, more difficult than forgiving the men who had actually killed her. “When I consider the fact that the man might have been brought by up a stepfather who wa a drunk, or who beat him or kicked hi out of the house, my resentment is not as easy to sustain,” he once said.130 At her trial, Renée said she did it for money; this Vilayat struggled to accept for years, and probably always struggled with the fact that Renée was acquitted.131 (For the record, I doubt that she did it for money because the sum that she received was so low. Perhaps there’s more to this story.)

In 1946, Noor was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre by France.132 In 1949, Noor was posthumously awarded the George Cross; he was one of only three women in the SOE to be given the award.133 Vilayat and Claire accepted it on her behalf. With that award, some of the story of her wartime service came out and she became a sensation—the Indian princess, daughter of a Sufi mystic, who had died bravely in the war. There are numerous testaments to her service around England today, including one at St. Paul’s Cathedral, a bust of Noor in London’s Gordon Square, and a blue plaque outside the home where she once lived.

Among Sufis, Noor is considered a saint.

That is the story of Noor-un-nissa Inayat Khan. I hope you enjoyed this episode. You can let me know your thoughts on Substack, Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks discover the podcast.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Clark. My research assistant is Niko Angell-Gargiulo. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email at hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com If you’d like to send us something, you can send it to P.O. Box 27162 Los Angeles CA 90027.

Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

Allwood, Greg. “Noor Inayat Khan – The Spy Hiding In A London Park.” Blog. Forces, July 20, 2021. https://www.forces.net/heritage/wwii/noor-inayat-khan-spy-hiding-london-park.

Curtis, Lara R. “Writing Resistance and the Question of Gender: Charlotte Delbo, Noor Inayat Khan, and Germaine Tillion.” University of Massachusetts Amherst. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://doi.org/10.7275/7752966.0.

Fazal Manzil. “History – Fazal Manzil.” Accessed January 2, 2024. https://fazalmanzil.org/history/.

Gonzalez, Pilar. “Indomitable Strength: Noor Inayat Khan, The Indian Princess And British Spy Who Fought Against The Nazis.” Lifestyle Asia, November 29, 2023. https://lifestyleasia-onemega.com/indomitable-strength-noor-inayat-khan-the-indian-princess-and-british-spy-who-fought-against-the-nazis/.

Gregory J. Wallance, opinion contributor. “The Century-Old Myth about Women in Espionage.” Text. The Hill (blog), October 17, 2017. https://thehill.com/opinion/international/355711-the-century-old-myth-about-women-in-espionage/.

Grewal, Herpreet Kaur. “Noor Inayat Khan: Remembering Britain’s Muslim War Heroine.” The Guardian, October 23, 2012, sec. Life and style. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/the-womens-blog-with-jane-martinson/2012/oct/23/noor-inayat-khan-britains-muslim-heroine.

INAYAT KHAN, Noor, ĀRYA SŪRA, and SUTTA-PITAKA Jātaka Selections English. Twenty Jātaka Tales. Retold [from the Pāli Jātaka and the Jātaka-Māla] by Noor Inayat, and Pictured H. Willebeek Le Mair. G.G. Harrap & Co.: London, 1939.

Magida, Arthur J. Code Name Madeleine: A Sufi Spy in Nazi-Occupied Paris. W. W. Norton & Company, 2020.

Second World War Experience Centre. “Noor Inayat Khan – SOE | SWWEC.” Accessed January 2, 2024. https://war-experience.org/lives/noor-inayat-khan-soe/.

Perrin, Nigel. “Noor Inayat Khan - Special Operations Executive (SOE) Agents in France.” SOE Agent Profiles. Accessed January 3, 2024. https://nigelperrin.com/soe-noor-inayat-khan.htm.

Posthumous George Cross for Noor Inayat Khan. n.d. Photograph. https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/postumous-george-cross-for-noor-inayat-khan-noor-inayat-news-photo/1360183965?adppopup=true.

Siddiqui, Usaid. “Noor Inayat Khan: The Forgotten Muslim Princess Who Fought Nazis.” Al Jazeera, October 28, 2020, sec. Features. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/10/28/noor-inayat-khan.

Wilson, Fiona. “Oxford: Hitler’s Choice.” Cherwell, September 30, 2007. https://www.cherwell.org/2007/09/30/oxford-hitlers-choice/.

www.girafficthemes.com, Giraffic Themes |. “HEARD.” Tumblr (blog). Accessed January 2, 2024. https://www.heard-journal.com/post/70068955449/noor-inayat-khan.

Just FYI, some of the links in this post are affiliate links. That just means if you click through and buy something, I’ll get a few cents of profit, but it won’t change the price for you.

Arthur J. Magida, Code Name Madeleine: A Sufi Spy in Nazi-Occupied Paris (W. W. Norton & Company, 2020).

Magida, 32

Magida, 16

Magida, 35

Magida, 22

Magida, 22

Magida, 22

Magida, 26

Magida, 26

Magida, 27

Magida, 27

Magida, 27

Magida, 37

“History – Fazal Manzil,” Fazal Manzil, accessed January 2, 2024, https://fazalmanzil.org/history/.

Usaid Siddiqui, “Noor Inayat Khan: The Forgotten Muslim Princess Who Fought Nazis,” Al Jazeera, October 28, 2020, sec. Features, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/10/28/noor-inayat-khan.

Magida, 41

Magida, 41

Magida, 41

Magida, 42

Magida, 44

Magida, 45

Magida, 47

Magida, 48

Lara R Curtis, “Writing Resistance and the Question of Gender: Charlotte Delbo, Noor Inayat Khan, and Germaine Tillion” (University of Massachusetts Amherst), accessed January 2, 2024, https://doi.org/10.7275/7752966.0.

Magida, 50

Magida, 51

“Noor Inayat Khan – SOE | SWWEC,” Second World War Experience Centre (blog), accessed January 2, 2024, https://war-experience.org/lives/noor-inayat-khan-soe/.

Magida, 52

Magida, 52

Magida, 57

Magida, 57

Magida, 58

Magida, 58

Magida, 61

Magida, 61

Magida, 64

Magida, 66

Fiona Wilson, “Oxford: Hitler’s Choice,” Cherwell, September 30, 2007, https://www.cherwell.org/2007/09/30/oxford-hitlers-choice/.

Magida, 73

Magida, 75

Siddiqui

Magida, 71

Magida, 83

Magida, 83

Magida, 86

Magida, 86

Magida, 87

Magida, 87

Magida, 89

Magida, 89

Magida, 91

Magida, 91

Magida, 95

Magida, 96

Magida, 96

Magida, 99

Magida, 103

Magida, 103

Magida, 105

Magida, 111

Magida, 112

Magida, 112

Magida, 115

Magida, 119

Magida, 124

Magida, 135

Magida, 136

Magida, 136

Magida, 137

Magida, 139

Magida, 137

Magida, 145

Magida, 140

Magida, 149

Magida, 149

Magida, 151

Magida, 141

Magida, 141

Magida, 142

Magida, 142

Magida, 142

Magida, 160

Magida, 144

Magida, 145

Magida, 145

Magida, 145

Magida, 146

Magida, 153

Magida, 154

Magida, 157

Magida, 164

Magida, 164

Magida, 166

Magida, 166

Magida, 166

Magida, 166

Magida, 172

Magida, 172

Magida, 172

Magida, 174

Magida, 179

Magida, 180

Magida, 180

Magida, 181

Magida, 182

Magida, 189

Magida, 189

Magida, 190

Magida, 191

Magida, 192

Magida, 197

Magida, 200

Magida, 200

Magida, 203

Magida, 208

Magida, 209

Magida, 210

Magida, 210

Magida, 211

Magida, 212

Magida, 212

Mgida, 220-222

Magida, 222

Magida, 225

Magida, 226

Magida, 235

Magida, 237

Magida, 239

Magida, 239

Magida, 241

Nigel Perrin, “Noor Inayat Khan - Special Operations Executive (SOE) Agents in France,” SOE Agent Profiles, accessed January 3, 2024, https://nigelperrin.com/soe-noor-inayat-khan.htm.

Siddiqui

Herpreet Kaur Grewal, “Noor Inayat Khan: Remembering Britain’s Muslim War Heroine,” The Guardian, October 23, 2012, sec. Life and style, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/the-womens-blog-with-jane-martinson/2012/oct/23/noor-inayat-khan-britains-muslim-heroine.

Share this post