Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Castellanos Clark, and today I’m covering Petra Herrera. She lived during the Mexican Revolution and briefly disguised herself as a man named Pedro to fight for Pancho Villa. This is a sort of special episode for me because I discovered Herrera while I was researching one of the chapters in my upcoming book. If you like this episode and enjoy stories about brave female fighters, you’re going to like my book! The pre-order link is in the show notes.

But before we jump into Petra Herrera’s life and how she fought for a better Mexico during the early 20th century, I first have to thank all the paying subscribers on Substack who help me make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! If you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber over on Substack! When you upgrade, you’ll get access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates on the upcoming Unruly Figures book. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

Unfortunately, we know very little about Herrera—even estimates of her birthday are generally “late 1800s, question mark?”1 My guess is that she was probably born around 1890 in Chihuahua, a Mexican state that borders Texas. This is based solely on the fact that she entered the Mexican Revolution there and at that time, a lot of people joined up when the military came calling in their hometown. From what I’ve read, it doesn’t seem like people traveled far to join the revolution, they just kind of answered the call of the traveling revolutionaries. A lot of people also joined the revolution in their late teens or twenties, so a birthdate around 1890 would put her around 23 years old when she joined the revolution, which is possibly even kind of older than might be normal.

So Herrera entered the world stage with a boom during Pancho Villa’s uprising against the dictatorial president of Mexico Porfirio Diaz. Diaz, and his three decades of rulership known as Porfiriato, were a time of great modernization of Mexico, but also really repressive rule. It’s seen as a, quote, “progressive dictatorship,” two words I never thought I’d string together until I started learning about Central America during this time.2

So Pancho Villa—who really deserves his own episode here one of these days—had started life as a bandit but then had become inspired by Francisco Madera, the losing candidate in the clearly farcical election which Diaz won (or “won”) in 1910. After being accused of fomenting revolution, Madera barely escaped Mexico with his life.

From his refuge in San Antonio, Texas, Madera wrote the Plan de San Luis Potosí, in which he declared himself the legitimate president of Mexico, and also called for an uprising to begin on November 20, 1910.3 Villa became one of the leaders of this revolution, calling for supporters and fighters from Chihuahua, Mexico. They were instrumental in pushing Diaz out of power and making Madera president of Mexico.

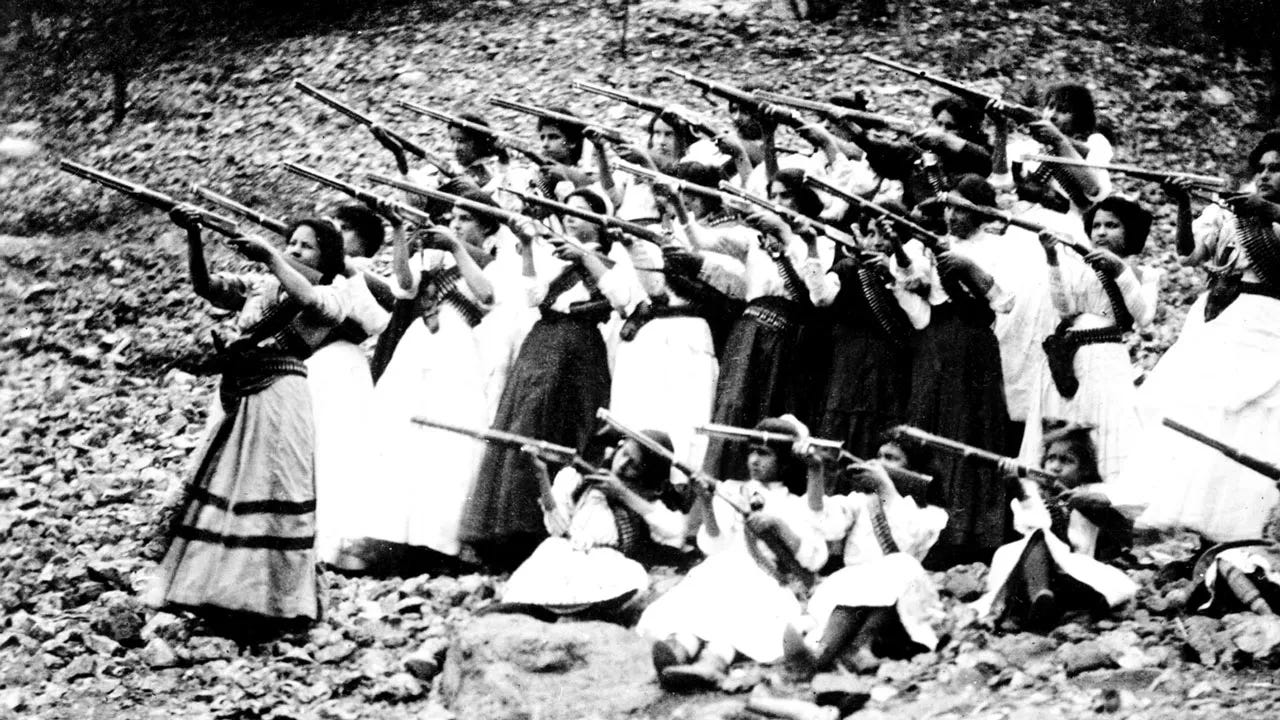

But things did not calm down. For reasons too complicated for our purposes, Madera was overthrown as well, and assassinated on February 22, 1913.4 His assassin, Victoriano Huerta, became the new president. Disgusted by this, Villa teamed up with Emiliano Zapata and Venustiano Carranza to overthrow Huerta. He controlled the Division del Norte, the northern part of the army right on the border with US. This might actually be why we know about Petra Herrera—because Pancho Villa was so close to the US border, he attracted a lot of like, lookiloos from the US! A lot of his revolutionary exploits were captured by Hollywood filmmakers who brought their cameras to film this revolution! This led to a lot of photos of soldaderas, women who followed the revolutionary army to cook, clean, nurse, and otherwise provide for the men who actually fought.

It’s worth noting that the soldaderas were treated poorly by the soldiers they supported. They were often recruited by force and then had to walk while the men rode horses, or if they were lucky they road on the top of trains while men sat in the shade inside.5 They, quote, “suffered rape, rejection, and victimization to such a degree that in 1925, Secretary of Defense General Joaquín Amaro…ordered them expelled from barracks.”6 Most of them had grown up in poverty, even misery, and remained miserable during the revolution, even the ones who had come by choice because they were following, “their men” to war.7 In stories about the war they are often romanticized; quote, “Men would write songs about Las Soldaderas, emphasizing their femininity and overt sexuality, in order to diminish their military contributions and accomplishments.”8 But the reality of their lives were far from romantic.

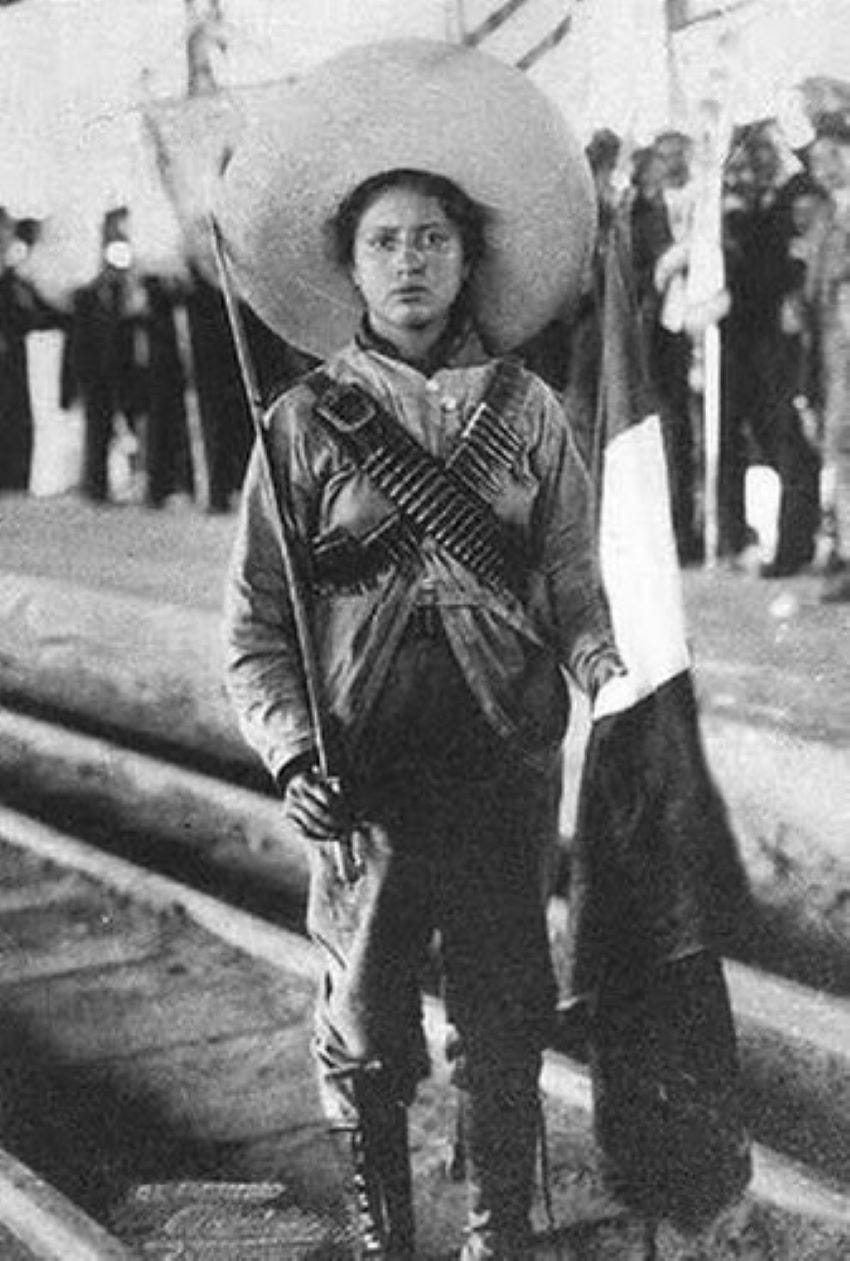

However, some women joined the revolution not to support the men but actually disguised as men to pick up weapons and fight. It seems like during the actual revolution these women—when their true identities as women were outed—were seen as a different group than the soldaderas. With time the two groups have become lumped together as part of an effort to dismiss how important female fighters were in the Mexican Revolution. Today some scholars are trying to wrest them apart again because they occupied very different roles during the revolution.9

Petra Herrera was one of these second women. Most accounts agree that she joined Pancho Villa’s revolutionary army in Chihuahua around 1913. It is possible that she joined earlier, in 1911, but she entered the historical record clearly in 1913. She joined up disguised as a man and called herself Pedro Herrera. She would even pretend to shave every day to keep up the act.10 She quickly established herself to be an excellent marksman, a reliable leader, and—you know—really good at blowing up bridges.11 According to anthropologist Laura Lee Cummings, Herrera and her troops used, quote, “grenades made of the sacks from goat [testicles] filled with shrapnel and gunpowder, with a fuse.”12 That she was great with explosives is something that almost everyone mentions. And I love that for her because for some reason women are always associated with quieter forms of attack and murder but it seems like Herrera was too big of a personality for that, and I like that.

Many women disguised themselves as men during the war, and they usually tried to stay disguised because it was safer to be perceived as a man in the face of marauding soldiers in the countryside, if you catch my drift. But Herrera’s disguise didn’t last long—once she felt that she had earned the trust of her fellow soldiers, she let down her trademark long braids and declared “I am a woman!”13 They accepted her apparently unanimously.

In January 1914, according to Atlas Obscura, the newspaper Mexican Herald published, quote, “Rebel leaders here were pleased to receive the first report from Peda [sic] Herrera, a young Mexican woman who is commanding a force of 200 men in the state of Durango. She holds the rank of captain in the rebel army.”14

A few months later, she and her troops were part of Villa’s fighting force in the Second Battle of Torreón, which they won after weeks of brutal fighting in March and April 1914. Villa did not give her credit, and her name doesn’t appear in any official record of the fight, but another soldier reported that Herrera, quote, “was the one who took Torreón, she turned off the lights when they entered the city.”15 He placed her at the front line of the battle. A later corrido, a type of traditional Mexican song that focuses on storytelling, names Herrera as a leader of the battle. It goes, quote,

On the 14th at midnight

They entered with great violence

Petra Herrera in front

Straight to the Presidential Office.16

Apparently, Herrera was caught and imprisoned by enemy forces during this battle!17 According to the song, she was taken to General Emiliano Lojero and defiantly said to his face, quote, “Viva Madero!”18 It’s unclear how she got free—I like to think she escaped rather than was released, but it’s also possibly that because of her gender Lojero totally underestimated her and let her go because she was quote-unquote “just” a woman. Regardless, we know that she did get free from enemy forces because another song extolls her fighting at a battle in May of that year.

The corrido, titled “Corrido del combate del 15 de Mayo en Torreón” also names Herrera as a great military leader, saying,

The valiant Petra Herrera

To battle she entered

Always being the first

To start the exchange of fire.

[…]

Long live Petra Herrera

Long live the Maderistas!19

According to author María Herrera-Sobek, only 3 other corridos include named women in actual battle scenes, so it is a pretty big deal that she’s named in two different songs.

However, none of this was enough for Villa. He never made Herrera a general or gave her real power within his army. This in spite of the fact that her success at Torreón gave Villa access to, quote, “heavy artillery, a half million rounds of ammunition, armored rail cars, the works.”20 Instead of promoting her, he basically patted her on the head and then took all the credit. She must have been fuming.

Now it’s unclear exactly when things changed. It seems like soon after Torreón, Herrera left Villa’s army and established her own independent force of all women. The numbers range wildly, with estimates from 25 women to 1,000 women, all fighting in this fight against Huerta. The number probably genuinely varied with time, but whether it was 25 or 1,000, it’s kind of astounding either way. It sounds like they were their own independent force, doing exactly what Pancho Villa and Venustiano Carranza were doing—waging a revolution.

Herrera was reportedly very protective of her female soldiers. Men were not allowed to stay the night, and she personally stayed up late on guard duty, where she used, quote, “any wayward male soldier that tried to get in as target practice.”21

It’s possible that it was this all-female battalion that fought in the Battle of Zacatecas in late June 1914. They, quote, “held the firing line” on the road that led out of the city, ensuring that federal troops couldn’t get away.22 Apparently, quote, “anyone who went there died there.”23

At some point, Herrera began to support Venustiano Carranza. He and Villa had begun as allies but by 1917 were enemies; maybe this was when Herrera began supporting Carranza. He would go on to become president of Mexico on May 1, 1917.

But Carranza was pretty moderate politically and rather conservative socially. When she had an audience with him and once again requested to be promoted to general, he refused. He recognized Herrera’s brave efforts for during the war and made her a colonel in his army—it’s unclear if she was a colonel in the national army, or if this was a post-dated colonel in his revolutionary army. And I make that distinction because just as quickly as he made her a colonel, he forced her and all of her female soldiers to retire. Just like that. According to one observer, they were dismissed, quote, “because it was an army of women.”24

Details get a bit murky again here. We know that Herrera wasn’t done trying to make Mexico better, and she apparently still believed in Carranza’s leadership. Instead of going home and leading a quiet life, she put her skills with a disguise to work and she became a spy for Carranza against Pancho Villa, who was still rabblerousing in northern Mexico. She moved to Jiménez, Chihuahua, a Villa stronghold, and became a bartender in a popular bar for Villa supporters.25 There, she collected intelligence and presumably reported it to someone.

Now, I have questions about how someone logistically becomes a spy for a leader who has dismissed them—who is she reporting to, if Carranza has fired her? My bet is that she was not exactly fired but just given a different job. The fighting was calming down at this point, and he might have thought that she was more useful with her ear to the ground back in what may have been her hometown. If she was originally from Jiménez, it would make perfect sense for her to return there and resume a quote-unquote “normal life.”

It’s unknown how effective her spying was. Unfortunately, she dies soon after this. One day at the bar—the exact day is not recorded—three drunk men shot her. We’re not sure why they shot her. Were they some of Pancho Villa’s soldiers who recognized her and knew she had betrayed Villa? Had they caught her listening and realized she was a spy? Was she trying to break up a drunken brawl? We don’t know. But she died of her injuries. Her doctor blamed her death on infection and quote, “fear of her attackers.”26 To me, that makes it seem like she died still undercover—clearly the doctor didn’t know who he was treating or he wouldn’t be saying that Petra Herrera died of fear.

Unfortunately, she’s not well remembered today. And in fact, a lot of female soldiers are not well-remembered in Mexico. There’s a lot of effort by modern Mexican feminists to change this, but they’re up against a century of erasure and minimization and over-sexualization of these very brave women. Mexican society was quite conservative at the time that these women were fighting and so their choice to go against expected norms of proper female behavior led to them being demonized in other ways. They’re often portrayed as having loose morals or being a little crazy, and definitely not worth remembering or idolizing. Scholars like Elizabeth Salas are helping to change that through their studies of soldaderas and female soldiers.

And again if you liked this story, I talk about another Mexican revolutionary in my book, Unruly Figures, coming out on March 5, 2024. You can pre-order it wherever books are sold.

That is the pretty short story of Petra Herrera! I hope you enjoyed this episode. You can let me know your thoughts on Substack, Twitter, and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks discover the podcast.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Clark. My research assistant is Niko Angell-Gargiulo. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email at hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com If you’d like to send us something, you can send it to P.O. Box 27162 Los Angeles CA 90027.

Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

Biography.com Editors. “Pancho Villa Biography.” In Biography. A&E Television Network, April 3, 2014. https://www.biography.com/military-figures/pancho-villa.

Fernández, Delia. “From Soldadera to Adelita: The Depiction of Women in the Mexican Revolution.” McNair Scholars Journal 13, no. 1 (2009).

“Francisco Madero | Mexican Revolutionary & President | Britannica.” In Encyclopædia Britannica, October 26, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Francisco-Madero.

Fuentes, Andrés Reséndez. “Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution.” The Americas 51, no. 4 (1995): 525–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/1007679.

Hernandez, Sonia. “Military Activities in Matamoros during the Mexican Revolution, 1910–1915,” n.d.

Herrera-Sobek, María. The Mexican Corrido: A Feminist Analysis. Indiana University Press, 1990.

La Jeunesse, Marilyn. “Mexican Revolutionary Petra Herrera Posed as a Man to Fight for Her Country.” Teen Vogue, April 1, 2019. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/mexican-revolutionary-petra-herrera-posed-as-a-man-to-fight.

———. “The Real History of Las Soldaderas, the Women Who Made the Mexican Revolution Possible.” Teen Vogue, March 12, 2019. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/the-real-history-of-las-soldaderas.

Monsiváis, Carlos. “Foreword.” In Sex in Revolution: Gender, Politics, and Power in Modern Mexico, edited by Jocelyn Olcott, Mary Kay Vaughan, and Cano, Gabriela, 35–56. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2007.

Orzulak, Jessica. “Searching for Soldaderas: The Women of the Mexican Revolution in Photographs.” PBS SoCal, May 21, 2015, sec. Arts & Culture. https://www.pbssocal.org/shows/artbound/searching-for-soldaderas-the-women-of-the-mexican-revolution-in-photographs.

Porath, Jason. “Petra Herrera: Soldadera Princess.” Rejected Princesses. Accessed November 18, 2023. https://www.rejectedprincesses.com/princesses/petra-herrera.

Rodés, Andrea. “Who Was Petra Herrera?” Al Día News, March 22, 2022, sec. Culture. https://aldianews.com/en/culture/heritage-and-history/who-was-petra-herrera.

Salas, Elizabeth. “Soldaderas: New Questions, New Sources.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 23, no. 3/4 (1995): 112–16.

Solá-Santiago, Frances. “Remembering Petra Herrera, the Unsung, Cross-Dressing Heroine Of the Mexican Revolution.” Remezcla. Accessed November 18, 2023. https://remezcla.com/features/culture/petra-herrera-mexican-revolution-heroine/.

“Venustiano Carranza | Mexican Revolutionary & President.” In Encyclopædia Britannica, November 9, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Venustiano-Carranza.

Wallenfeldt, Jeff. “Porfiriato | History, Facts, & Mexican Revolution | Britannica.” In Encyclopædia Britannica, August 9, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Porfiriato.

White, April. “The Mexican Revolutionary Who Fought for Freedom on the Battlefield and in the Barroom.” Atlas Obscura, March 11, 2022. http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/petra-herrera-mexican-revoultion-spy.

Jason Porath, “Petra Herrera: Soldadera Princess,” Rejected Princesses, accessed November 18, 2023, https://www.rejectedprincesses.com/princesses/petra-herrera.

Jeff Wallenfeldt, “Porfiriato | History, Facts, & Mexican Revolution | Britannica,” in Encyclopædia Britannica, August 9, 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Porfiriato.

“Francisco Madero | Mexican Revolutionary & President | Britannica,” in Encyclopædia Britannica, October 26, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Francisco-Madero.

Biography.com Editors, “Pancho Villa Biography,” in Biography (A&E Television Network, April 3, 2014), https://www.biography.com/military-figures/pancho-villa.

Carlos Monsiváis, “Foreword,” in Sex in Revolution: Gender, Politics, and Power in Modern Mexico, ed. Jocelyn Olcott, Mary Kay Vaughan, and Cano, Gabriela (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2007), 35–56.

Monsiváis, 8

Monsiváis, 8

Marilyn La Jeunesse, “The Real History of Las Soldaderas, the Women Who Made the Mexican Revolution Possible,” Teen Vogue, March 12, 2019, https://www.teenvogue.com/story/the-real-history-of-las-soldaderas.

Andrés Reséndez Fuentes, “Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution,” The Americas 51, no. 4 (1995): 525–53, https://doi.org/10.2307/1007679.

Andrea Rodés, “Who Was Petra Herrera?,” Al Día News, March 22, 2022, sec. Culture, https://aldianews.com/en/culture/heritage-and-history/who-was-petra-herrera.

Jason Porath, “Petra Herrera: Soldadera Princess,” Rejected Princesses, accessed November 18, 2023, https://www.rejectedprincesses.com/princesses/petra-herrera.

Elizabeth Salas, “Soldaderas: New Questions, New Sources,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 23, no. 3/4 (1995): 112–16.

April White, “The Mexican Revolutionary Who Fought for Freedom on the Battlefield and in the Barroom,” Atlas Obscura, March 11, 2022, http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/petra-herrera-mexican-revoultion-spy.

White

Porath

María Herrera-Sobek, The Mexican Corrido: A Feminist Analysis (Indiana University Press, 1990).

Herrera-Sobek, 93

Herrera-Sobek, 93

Herrera-Sobek, 94

Porath

Porath

Salas, 114

Salas, 114

White

White

White

Share this post