Hello everyone and welcome to season three of the Unruly Figures! I’m so excited to start another season of this super fun show with y’all.

Any guesses for what is coming this season? I have some high-profile figures and some folks that you may have never heard of, and I’m excited to talk about all of these rule-breakers with you.

Have you told a friend about the podcast yet? Now is a great time!

Don’t forget, all merch is currently 15% off to celebrate the shop’s launch! Use code LAUNCH15 for 15% off until September 10!

Okay, on to the show.

🎙️ Transcript

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I want to welcome you back for season three of the podcast! I cannot believe we’re already in season three, I’m very excited. I have a ton of exciting content for you this season, some of which you might have already guessed at when you heard the previews.

A few updates for the show going into season 3: The biggest is that we have new backing music! You’re hearing it now! It’s by my friend Danny Wolf, of the excellent band Wolf and Love! Up until now, I’ve been using music provided by Spotify for podcasters, but I’ve been getting nervous about it possibly going away considering all of the other changes Spotify is making. I’ll take a moment of silence so we can all bop along to that together.

Thanks, Danny!

The second big announcement is that I have finally opened a merch store! I’ve been working on it for almost a year now because I couldn’t find a place that had high-quality stuff that was also flexible with designs and cute. You can check it out here. There is some seriously cute stuff in there. And to celebrate the launch, I’m giving everyone 15% off until September 9th, 2023. Use code LAUNCH15.

And the third and final update is just that paying subscribers on Substack now have the ability to create threads in our private chat, so if you’ve been wanting to talk to other Unruly Figures fans more, that just got a lot easier!

Okay, now for the actual episode!

Today I’m covering Blanche Ames Ames. No, that’s not a typo and no, I’m not stuttering—her name is Blanche Ames Ames. She was a famous botanical artist, a women’s rights activist, a political cartoonist, and an inventor with an insatiable curiosity that led to three patents in her name. She was, simply put, very cool. And yet, somehow, there’s no biography written of her. Today I’m relying heavily on a Ph.D. dissertation on Blanche written by Anne Biller Clark, of no relation to me, but somehow there is not—yet!—a biography of this incredible woman. There is, however, a documentary of her called Borderland that you can rent online for $10. Anyway, let’s hop right in!

Blanche Ames was born in the Highlands, New Jersey, on February 18, 1878, to Adelbert Ames and Blanche Butler Ames. Both of her parents came from notable American families—her maternal grandfather was Benjamin Butler, a Union Army general who served as the governor of Massachusetts and in the House of Representatives. Butler is sometimes remembered by historians as "Benjamin ‘the Beast’ Butler” because of his radical and loud views on equal rights for Black Americans and women’s suffrage in the mid-19th century.1 Her paternal grandfather, Jesse Ames, had served as a sea captain for many years before buying a mill in Minnesota and christening it Ames Mill—they would become famous for the Malt-O-Meal cereal lines. Her father, Adelbert Ames, was also a Union Army general and served as a Reconstructionist Mississippi senator, then governor, before moving the family to Massachusetts. Her mother, Blanche Butler Ames, wrote a series of famous letters reflecting on the life of a woman from the North living in the South during Reconstruction; they’ve been digitized and can be found online.

Blanche had five siblings—three sisters and two brothers. Her younger brother, Adlerbert Ames Jr., grew up to be quite famous himself. He is remembered today for his incredible optical illusions, including the Ames Window and the Ames Room. I imagine a childhood with someone like Adelbert Jr. was fun.

Their childhood was “peaceful and comfortable.”2 In 1887, young Blanche wrote to her brother that she had been allowed to adopt a turkey of her own, which she was delighted by.3 In 1893, the family moved to Massachusetts. The family was not particularly religious, which is interesting considering that, at this time, political reform often relied on religion as an organizing principle.4 There are recurring mentions of Unitarianism in the family, but nothing devout. Blanche’s parents were interested in modern, quote, “controversial theories, Darwin and the Theologians, Freud, Jung, and their detractors… Scientific and religious theories were discussed as their enterprising children vied with each other to bring forward the latest treasures of thought.”5 Later in her life, Blanche would write, quote, “I believe in the Motherhood of God…sacredness of the human body…salvation through economic, social and spiritual freedom…we are now living in Eternity as much as we ever shall...there is no devil but fear…” and more.6 She never really expanded on this, but it sounds very humanist to me.

In 1893, the family traveled to Chicago for the World’s Columbian Expedition, which was held in Jackson Park. It celebrated the 400-year anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. Her diary is full of, quote, “snippy observations” about the fair and the people attending; she’s never more clearly upper-class than when she’s making snide remarks about other people’s outfits.7 Nevertheless, she enjoyed ice cream sodas but found the mining and engineering displays boring. Surprisingly, she also didn’t enjoy the art exhibits!

We don’t know much more than this, unfortunately. All accounts skip straight from accounts of her family lineage to her time at Smith College, which she graduated from in 1899. She was president of her class and got both a bachelor’s degree and a separate degree from Smith’s art school.8

We know that by the time she graduated, Blanche was, quote, “an ardent feminist.”9 She wrote in her diary, quote, “As long as I can remember, I never could see a truly reasonable argument against women’s suffrage. They are all so trivial.”10 She also supported the Spanish-American War although other students didn’t, and she, quote, “refused to admire male faculty and lecturers merely because of the high opinions they held of themselves.”11

One great thing that her diaries give us is insight into Blanche’s head and opinion of herself. For instance, while in college another young woman prevented her from joining the glee club, despite numerous professors noting that Blanche had a lovely singing voice. The next semester, Blanche could have prevented the girl from joining the honor society, which Blanche was president of, but didn’t. In her journal, she, quote, “recorded disgust in her own ‘goody goody’ smugness over not taking her revenge.”12 It seems Blanche could not help but be the bigger person, even when she annoyed herself with it.

But Blanche wasn’t perfect—there was an incident with a Miss Wood whom Blanche had become friends with. For Wood, the friendship had blossomed into romantic feelings, which Blanche did not return. In her diary, Blanche wrote that her crush was, quote,

“most degrading… I actually blush to write the word of all things most to be despised, that is the worst… Never for one moment did I think of her as anything but a friend… I was innocent of even the idea. I did not know that such a thing existed and we use to have fine times together.”13

After learning of her feelings, Blanche described Miss Wood as “unhealthy, silly, mawkish.”14 Which reflects a couple of larger societal turns at the end of the nineteenth century. For one, doctors—and by that I mean men—were finally understanding not only that women could enjoy sex and want it for themselves, but also that they could be sexually attracted to one another. For centuries until this period, a lot of European doctors believed women only endured sex for their husbands’ sake, which makes you really sad for all their wives, doesn’t it? They knew men could experience same-sex attraction but really struggled to believe women could because they didn’t believe women enjoyed sex. But in the late 1800s, we finally see them realizing that women could want to have sex with each other, and in the 1900s, we start to see a lot of literature about socializing girls and boys together so they won’t “get confused” and be attracted to their own sex. Blanche would have been exposed to this reading material at home, since her parents kept up with all the most up-to-date scientific and social science materials.

So Blanche was a little homophobic as a college student, as she had been raised to be, though the word would not be invented for a few more decades.

Briefly, in 1898, Blanche worked as a nurse for the troops in Long Island during the Spanish-American War, which only lasted 8 months. Though there aren’t many formal records of her service, it sounds like she worked at Camp Wikoff, a military hospital on Long Island that saw 250 veterans of the Spanish-American War die of yellow fever and typhus while in quarantine. It was a huge bungling of the concept of quarantine and it indirectly led the the establishment of Walter Reed Hospital!15 From what I’ve read, it sounds like Blanche was lucky to not contract yellow fever or typhus herself.

It was also around this time that Blanche finally got into art. She began attending life-drawing classes and mostly studied painting, though she did a little sculpting as well. Excited by the praise she was receiving from her art teachers, she wrote to her mother, quote, “I can see visions of a studio with beautiful pictures by my own hands, great casts of men and horse and crocodiles—I don’t know why I think of them—and elephants—I saw some in a Sunday paper, and portraits and dainty Venuses and things possible and impossible.”16

As an adult, Blanche has been described as “witty, warm and lively.”17 She apparently had an ironic sense of humor that she used to, quote, “help her control difficult situations, that is, to help her to preserve that edge of detachment that separates the fanatic from the leader.”18 She balanced optimism and pragmatism, which helped her remain in the fights for women’s suffrage and female bodily autonomy over many years. Arguably she saw fighting for reform as a “duty, which she upheld all her very long life.”19

On February 17 1899, the day before her 21st birthday, Blanche received a set of art books bound in yellow leather and gold, with her name printed on the front. It was an extravagant gift, then and now, and she suspected the gift giver was a wealthy man named Oakes Ames, a Harvard botanist who would go on to become a renowned expert on orchids. As a “proper young woman,” she didn’t feel like she could write to him to thank him, especially because she didn’t believe he had any right to, quote, “presume that he could outrage custom and dare to send me so expensive a present.”20 Blanche initially thought that they could be friends, but Oakes never thought so—in his own diary, he intended to marry Blanche as soon as he met her while serving in the same voluntary regiment as her brother Butler.21

While courting, Oakes gifted Blanche flowers, she described them as “the queerest orchids,” in a letter to her mother.22 After they got engaged, he gave her a microscope so she could examine them more closely. It’s not clear to me whether she began illustrating the orchids right away, but she quickly became known as the foremost botanical illustrator of her age.

In 1900, Blanche Ames married Oakes. Interestingly, his father had also been a governor, though he’d served in Massachusetts. Just to be clear, Oakes was not in any way related to her, despite their matching last names; after their marriage, she began going by Blanche Ames Ames. Though their marriage has long been characterized as a perfect meeting of the mind and spirit, the early years were not as happy; it took them a while to figure each other out and how they fit together.

Oakes, it seems, was a feminist in theory and spirit, but not so much in practice. Or, at least, it took a while for his actions to catch up with his beliefs. He, quote, “sought to dominate the marriage ceremony planned by her family,” choosing the minister against her wishes.23 He also eliminated the ring portion of the ceremony, against Blanche’s wishes, deeming the rings a, quote, “token of bondage.”24 This was in line with many feminists of the day, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, but Blanche and her family didn’t like it. She ended up wearing two rings given to her by her mother and mother-in-law.

The Lowell Daily Courier covered their wedding on May 16. In addition to notes about what everyone was wearing, they especially pointed out that the marriage certificate listed an occupation for Blanche—”artist.”25 This differed from most society girls, whose occupation was given as “at home.”26

At first, the young couple lived together with Oakes’s mother, and this was another issue.27 Blanche was a very strong-willed woman and she didn’t like not being in charge of her own home, nor being told what to do by a woman she barely knew. They often clashed over their roles in the relationship, with Oakes both advocating for the New Woman ideal politically, but finding it irksome in his own wife. In a long exchange of furious letters that spawned from Blanche choosing to take their children to her parents’s home while someone in Oakes’s home was sick with pneumonia, Blanche eventually wrote, quote, “I find that marriage has added to my burdens and has given me none of the personal care and attention that would make these burdens easier to bear.”28 It wasn’t until they built a new home, Borderland, and moved there, that their relationship developed.

If you’ve heard of Oakes Ames and Blanche Ames before today, it might be in connection with this home—the Oakes Mansion, as it’s known today, is the centerpiece of Borderland State Park in Massachusetts. The residence has been the setting for many films, including the first Knives Out, directed by Rian Johnson. It’s my understanding that the house is rarely open to the public, but you can tour it at certain times of the year.

Borderland was a symbolic name for both of them. Not only was it on the border of several towns, and outside the borders of both of their family’s homes, but it also symbolized how they, quote, “willingly chose to live their lives on the borderland of acceptable behavior for their class.”29 Her work on the birth control campaigns, as well as his work teaching instead of pursuing law or business made them both rebels by the standards of their social and economic class.

Once they figured each other out, Oakes and Blanche became great collaborators. With her art school degree, she became a really wonderful illustrator and cartoonist. They first worked together in 1902, on a book on orchids. She began illustrating his botanical texts with incredibly detailed line drawings which showed orchids at all stages of development. She would go on to illustrate all seven volumes of Oakes’s seminal work Orchidaceae: Illustrations and Studies of the Family Orchidaceae (1901-1922). The difference between botanical art and botanical illustration, it should be noticed, is one of intention—quote, “Botanical illustration emphasizes scientific accuracy while botanical art emphasizes artistic expression.”30 They often traveled together on his orchid-collecting trips, including an early trip to Cuba and, eventually, a 1915 trip to Brazil.

On this trip to Brazil, Blanche and Oakes were traveling with Swedish-Brazilian botanist Johan Albert Constantin Löfgren when Blanche stumbled across a species of orchid thought to be extinct.31 Löfgren immediately recorded and described it, in case they never found another—apparently, another specimen of the same plant had been found 19 years before but had not been seen since. He named it after Blanche, Leptotes blanche-amesiae. The plant was later placed in a different genus and renamed Loefgrenianthus blanche-amesiae to honor both of them.32

It’s also worth noting a legend about Blanche. Apparently on another orchid-collecting trip, this time in the Yucatan peninsula, she and Oakes became stranded in the jungle. Oakes didn’t know anything about cars, and the driver didn’t know what the problem was either. So apparently Blanche, quote, “pulled a hairpin from her chignon, extracted a bullet from her revolver, and set to repairing the carburetor” while they stood by helplessly.33 She successfully started the car, but apparently, no one knows how and she never bothered to tell anyone. If you know how a carburetor can be fixed with a hairpin and a bullet, please get in touch because I’m dying to know.

In 1901, Blanche gave birth to the couple’s first child, Pauline. Two years later, she had Oliver, then in 1906 came Amyas, and their fourth and last child, Evelyn, was born in 1910. If I haven’t made that clear by describing how they custom-build a mansion, the family was wealthy, so they could afford to hire help so that Blanche and Oakes could both be parents and have careers. He was a professor of botany at Harvard and in the course of his duties there he was the head of the university’s herbarium, but they also kept a greenhouse on their property, as well as a studio for her. It helps, of course, that Oakes and Blanche grew together and collaborated, supporting each others’ careers both emotionally and materially. Blanche never gave up her artistic practice even while managing the large house and raising her children.

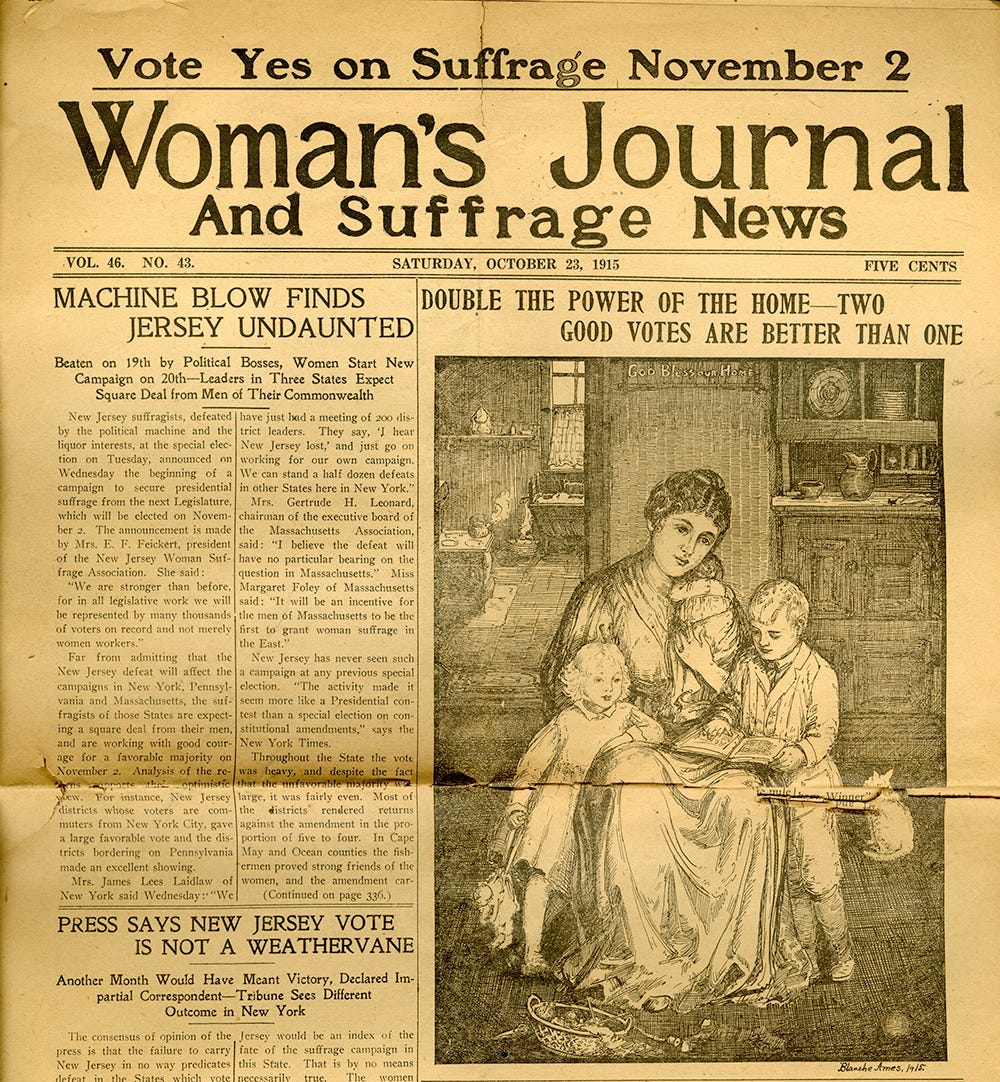

Sometime around 1904, Blanche was listed for the first time on the masthead of the now-defunct Woman’s Journal. The weekly publication had been founded in 1870 to further women’s issues. It was moderate politically but leaned progressive. They were in favor of women’s suffrage and voting rights, though they did also support the temperance movement; they refused to print ads for tobacco, alcohol, or drugs. It seems she began her career as a political cartoonist then.

As Anne Biller Clark points out in her Ph.D. thesis, her choice of political cartooning as a medium is interesting because her maternal grandfather was often the target of political cartoonist Thomas Nast. Clark wonders if she had a, quote, “more direct understanding of the power of political cartoons to influence (and annoy) than did other pro-suffrage and artistically inflicted young women” because of this family connection.34 Blanche seems to have had a deep interest in political cartoons in general; according to Clark, quote, “possibly the finest collection of suffrage cartoons” was curated by Blanche and Oakes via a newspaper clipping service that they employed in 1915 and 1916—”literally hundreds of splendid political cartoons” have been preserved thanks to them.35

Blanche’s cartoons were also often published in the Boston Transcript newspaper, which openly sympathized with suffrage. This is a big deal because the Transcript was much more mainstream than the Woman’s Journal. It had a much wider audience than white middle-class women, including men, for one, and people of all classes. Getting her work published there meant it was noticed by more people, further expanding her audience. This expanded audience eventually included former-president William Howard Taft, who wrote an editorial in the Saturday Evening Post denouncing her June 5, 1915 cartoon in Woman’s Journal and Suffrage News. He wrote, quote, “The implications from such a cartoon are so unjust to opponents of suffrage that they ought not to aid the cause.”36 If you want to see the cartoon he was mad about, it is in the Substack.

The cartoon shows two upper-class white Americans sitting on a dock watching other women drown. The man holds a life preserver saying “Votes for Women” and promises to throw it in when all women agree they want it; the upper-class woman next to him says she doesn’t need it. It was as much a critique of upper-class women who didn’t support suffrage as it was of men who didn’t want women to have the vote. It’s great, but I’m not surprised that conservative Taft, who opposed suffrage on the basis that women were too emotional, was upset about it since it aligned men and women on the same emotional level of ambivalence.

In September 1915, Blanche drew and published a response to Taft’s op-ed titled “Our Answer to Mr. Taft.” Set on the same dock as the first, it shows Taft with his foot on the life preserver now, but it features other women who have used a life preserver saying “Votes for Women” to get out of the water. They each represent a different state and unique issue that had been passed since women had been given the right to vote in individual states. Each woman is dripping wet but she clearly saved herself—a huge difference from how women were usually portrayed as passive rather than active roles.

What I also really love about the women Blanche drew here is that they’re regular women of all ages. They’re all white, but there are older women, middle-aged women, and young girls, all of a middle or lower economic or social class. This is also really different from the women who were usually portrayed in pro-suffrage cartoons. It was usually beautiful upper-class women who represented the rights of women to vote.

Part of what set Blanche apart from other suffragists was that she had more obviously benefitted from increasing women’s rights in the past and was in turn trying to expand rights for others. She was one of less than a dozen women artists who had received formal art training and school that had once been closed to them and had decided to use that art training to promote their political agenda.37 She was no Lou Rogers, a pioneering socialist who wielded her cartoons with bravery and ease, but they were peers and Blanche belonged to a small but significant group of artists.

One of the things that I think makes Blanche special in the annals of early women’s suffragists is her dedication to actual equality. Instead of seeing non-rich, non-white groups as competition for equal rights, Blanche was careful to depict everyone with respect in her cartoons. While racist images abound in the early political cartoons and rhetoric by women, even ones working for equality, this is not so with Blanche Ames’ work. While Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton allowed themselves to, quote, “[pander] to racism as a pragmatic tactic to advance their feminist cause,” Blanche knew better.38

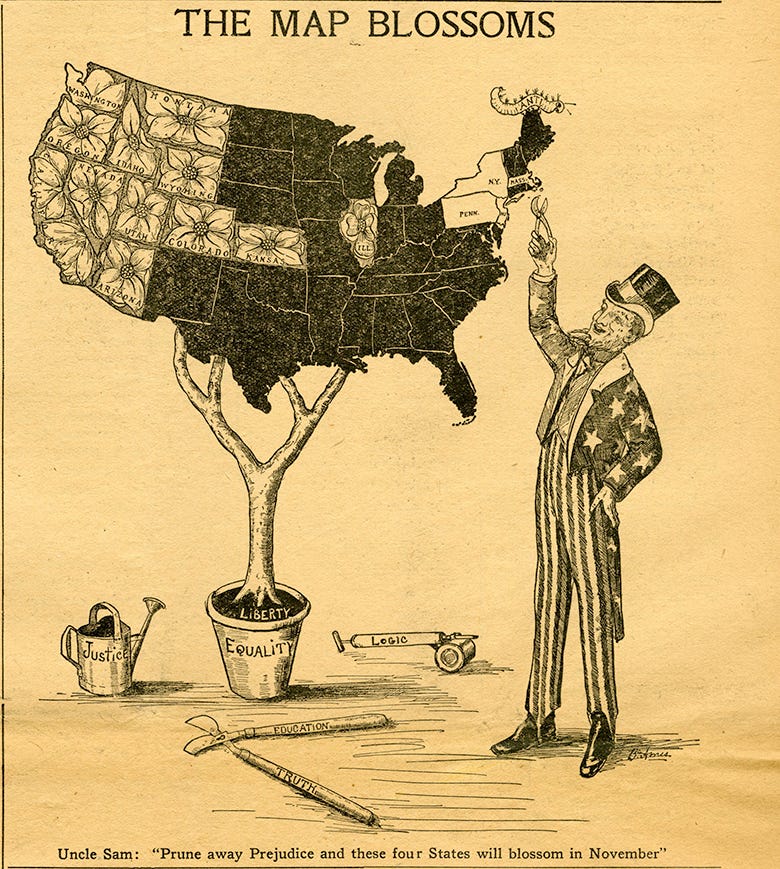

One of her most significant cartoons is called “Woman Suffrage Flowers,” though it’s also sometimes titled “The Map Blossoms.” It shows Uncle Sam caring for a plant shaped like the 48 continental states, with flowers denoting the states that had already allowed women to vote. He is also shown holding a pair of scissors to prune away prejudice, allowing New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts to, quote, “blossom in November.”39 It was published in the Woman’s Journal on May 22, 1915. Perched on top of Maine, a caterpillar threatens the suffrage flowers. It had a huge impact at the time, and it is still one of the more memorable suffrage cartoons.

In addition to her cartooning, in 1914 we have records of Blanche marching in the historic Boston Suffrage March, the first of its kind in Massachusetts. An estimated 15,000 people marched that day, from young students to celebrities of the suffrage movement.40 Blanche also held pro-suffrage teas in her home, which was a place for women to discuss the issues and acted as fundraisers for the cause.41 These were very standard forms of political activity for socialites like Blanche Ames.

What was less standard was the way she also adopted the more aggressive tactics of the National Women’s Party by, quote, “targeting anti-suffrage politicians for electoral defeat.”42 She clearly had a lot more sympathy for women who occupied other social classes than her peers; she is quoted in a magazine interview in 1915 as saying that all jobs should be open to all women so they could all support themselves independently; more conservative feminists, like the readers of Woman’s Journal, might have balked at that suggestion.43

In 1916, Blanche heard Margaret Sanger speak in Boston. Blanche was struck by, quote, “Sanger’s beauty and gentle demeanor, but even more by her ‘spirit and eloquence’ and the diversity of her supporters, which ranged from radicals, anarchists, socialists, Republicans, Democrats and members of many religions.”44 She had an incredibly strong reaction to Sanger’s speech and the entire aim of her work shifted. That same year, she and Cerise Carman Jack, another wife of another Harvard professor, founded the Birth Control League of Massachusetts. Blanche was quickly elected as the League’s first president, and though the strength and effectiveness of the league wavered over the years, she remained nominally in charge for years.

All that said, despite her waning work in advocating for women’s rights to vote, Blanche was in the gallery when the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote in the United States, was ratified by the Massachusetts Legislature on June 25, 1919.45

In addition to starting the Birth Control League, her suffrage cartoons stopped appearing in the Woman’s Journal. However, she did not pick up cartooning for birth control. In her thesis about Blanche, Clark supposes that, quote, “Blanche’s cartoons for suffrage found a ready market because suffrage was respectable and cartoons on the subject publishable, whereas birth control was much more controversial and cartoons on the subject did not find wide distribution.”46 It wasn’t so much about her, it seems, than the subject.

That said, why not continue publishing cartoons in support of women’s suffrage in addition to her work for birth control? According to Clark, it was in 1917 that Blanche stopped publishing her cartoons in Woman’s Journal, but she only speculated as to why. It may be that she just didn’t have the time and energy to raise four kids, to illustrate her husband’s manuscripts, and to cartoon for two different causes. That’s a lot, even for someone with unlimited reserves of energy. But notably, 1917 is also the year that the Woman’s Journal was bought by Carrie Chapman Catt's Woman Suffrage Commission for $50,000. The magazine was merged with two others: The Woman Voter, which was the official journal of the Woman Suffrage Party, and National Suffrage News, the publication of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. With this merger, the new publication became known as The Woman Citizen.

I say all this because if you merge three magazines, you’re going to have too much staff. The new weekly journal was still only 10 pages long, so I imagine several people suddenly had much less work to do. It also didn’t seem to have a big focus on cartoons—each cover had some kind of political cartoon, but that’s all. Over on Archive.org, I looked at all the covers they published for the rest of 1917 and it seems like they had two illustrators they already used, the very famous Lou Rogers, and someone else whose signature is indecipherable except that the last name starts with a B. To me, it sounds like she was more or less laid off.

Regardless, Blanche had mentally moved on to the fight to legalize birth control by this point. Which is perfectly in line with her larger views of giving women autonomy and control over their lives. The fact that the cause was supported by a diverse audience with different motivations made it all the better for her—Blanche had always supported a bootleggers and baptists argument; meaning that she was always prepared to accept allies where she could find them, even if they found themselves supporting the same goal for very different reasons.

However, while votes for women had been a respectable cause, especially for upper-class women, birth control was not. Even other feminists were against birth control, suggesting that married couples who wished to reduce the number of children should just avoid "excessive sexual indulgence” instead of legalizing birth control, which found popular opponents in the Catholic church.47 The cause was seen as downright disreputable at this point, often characterized as immoral, obscene, and/or lewd. Both the National Women’s Party and the League of Women Voters wouldn’t take up the issue, so Blanche’s choice to lean into it was a genuine risk not only to her reputation and social position but also her income! She was done cartooning, but if her name was too tarnished, there was also no going back and it could have impacted her husband’s work as well.

And she did face opposition. As she became more involved in the fight for birth control, she was, quote, “lambasted repeatedly in the press as a frivolous socialite who preferred poodles to children, and even as a person of neither religion nor morality.”48 But she forged on—she devoted a considerable amount of time to this. Not only did she advocate for birth control, forming coalitions of diverse groups of people through her charm and wealth, but Blanche actually began to invent things. We know she began to experiment with creating homemade contraceptive pessaries from rubber canning jar rings. She also tried to make a homemade diaphragm from a baby’s teething ring, and apparently even published formulas for spermicidal jellies.49 Her goal was for women to be able to circumvent legal powers with easy-to-obtain household objects. Neither really worked, but I think it’s really cool that she tried. And as we’ll see, she went on to invent more things.

People may wonder, so I’ll just say: We don’t fully know if Blanche had personal reasons for wanting to legalize birth control. She gave birth to four children, but whether that impacted her desire for birth control is unclear. Blanche’s letters to her daughters haven’t been digitized, at least that I’ve seen, so I haven’t been able to see if she talked about her experience with childbirth with them, or if she advised them in any way. We don’t know if she herself used any form of contraception. All we have are her public statements and letters to other activists. She wrote with passion about the, quote, “exhaustion of the mother’s body and spirit by too frequent child-bearing,” among other things.50

I mentioned before that Blanche helped start the chapter of the Birth Control League in 1916. Their chapter of the organization was, unfortunately, born in response to the arrest of Van Kleeck Allison, a man who was arrested when he gave a police officer a pamphlet on limiting births among the poor. Under the Comstock law, these kinds of pamphlets were illegal. I said unfortunately because eugenicists of the day supported birth control as part of their argument for limiting the population of so-called undesirable groups, which included poor people of color. There’s not a lot of information about Allison out there, so I’m not a hundred percent sure that Allison was a eugenicist, but it sure sounds like it from this arrest record. A defense committee was put together, which included Blanche—this is the downside of her pragmatism and willingness to find allies anywhere. She ended up defending a eugenicist because he supported legalizing birth control.

The early Birth Control League of Massachusetts believed that banning contraceptives and contraceptive information was a free speech issue. The League began to lobby legislators in the state to at least repeal the Comstock law, so they could at least spread information about birth control, but the all-male legislature was disinclined to support the cause. Massachusetts Supreme Court Chief Justice Rugg declared that statutes against birth control were, quote, “designed to promote public morals…to protect purity, to preserve chastity, to encourage continence and self restraint…to engender in the state and nation a virile and virtuous race of men and women.”51 Under the Comstock Law, and the strict enforcement of it in Massachusetts, the League was limited to word of mouth for informing the public about birth control.

When the free speech argument didn’t work, Blanche began to rail against the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. She accused the Church of, quote, “muddled thinking in linking abortion and contraception,” pointing out that adequate contraception prevented abortions.52 She also pointed out that Protestants accepted some forms of birth control, and that it was unfair that the dominance of the Catholic church prevented non-Catholics from living according to their faith. She even leaned on Yankee hatred of alleged control from Rome—she denounced the pope as a dictator and mocked the idea of celibate men forcing women to bear children, likening forced pregnancy and birth to sexual slavery with Church support.53 In a private article she never published, she took on the Church’s idea that birth control de-sanctified marriage by saying that the real reason the Church forbade birth control was to, quote, “increase its membership at the expense of women.”54 It’s interesting that she went this route since she didn’t grow up religious. And that shows in her arguments—she simply couldn’t argue religious doctrine the way people who had been in church all their lives could.

So when the freedom-from-the-tyranny-of-Rome argument didn’t work, Blanche focused on her real point: Women should have, quote, “freedom of choice” in all sexual matters in case husbands who had, quote, “no restraint in relations and bearing children, could render their marital rights merely bestial.”55

For Blanche, birth control was a private women’s issue; she argued against medically-dictated birth control. She believed that if birth control was limited to doctors and hospitals, it would limit access to women who were somehow ill. Worse, since medical careers were limited to men at the time, letting men control birth control left women to be controlled by, quote, “the caprice of doctors.”56

In 1918, the Birth Control League voted to raise $2,000 to open a birth control clinic and began to follow Margaret Sanger’s example and began holding rallies, public meetings, and debates to make birth control a public issue. Those same clinics were eventually raided and shut down, and these public meetings were often starting points for huge conflict. Blanche continued reaching across ideological divides to invite people into the conversation, which did not always go smoothly—even groups who agreed that birth control should be legalized had different ideas of what birth control should mean and how it should be used. Blanche did not agree with eugenicists who wanted to force birth control on the poor, because they were seen as “biologically unfit.”57 For Blanche, birth control was a necessary option for poor women who were being forced to give birth to more children than they wanted or could support. When members of the League began to lean more into the eugenicist argument 19 years later, Blanche resigned from the presidency in 1937. Her commitment to birth control never wavered.

At some point, Blanche became a supporter of the New England Women’s Hospital, which trained women to become doctors and nurses and to care for female patients. It did well for a while but began to struggle under the conservative backlash of the 1930s. Like the professional side of birth control, the hospital was, quote, “increasingly run for and by male physicians.”58

In 1940, when she was 62 years old, she was still advocating for birth control and against the control of women’s bodies by the male church hierarchy. She wrote a column in Atlantic Monthly, focusing especially on the fact that the Church’s insistence that Catholics multiply on the earth only impacted the wife, who, quote, “incurs all the dangers of pregnancy, often death.”59 She also pointed out that, quote, “no solicitude whatever is expressed [by the Church] for the welfare of the children to be conceived.”60 If that argument sounds vaguely familiar, it’s because this is still a significant argument for pro-choice advocates against the church and conservative political parties.

However, by 1940, Blanche’s style of argument for the autonomy of women had fallen out of favor. In 1942, the Planned Parenthood Federation of America was born as a “single-issue, otherwise apolitical. organization, which stressed its support for family values rather than its support for women’s rights and autonomy.”61 The birth control movement had been tamed, dominated by male doctors and legislated away from female leaders.

Her political activism influenced her children. Her youngest daughter, Evelyn, grew up to become the founder and first president of the Planned Parenthood of Nashville, Tennessee. Her older daughter, Pauline, served on the board of the International Planned Parenthood Federation and received awards for that work.

To me, everything I’ve already said sounds like enough to occupy somewhere for a lifetime. But, amazingly, Blanche had more on her plate besides her illustrations for Oakes, her political activism, and raising a family.

In the early 1920s, she and her brother Adelbert, of illusions fame, invented a system of color charts for matching colors exactly. Blanche tested the system by painting copies of the Great Masters herself, though I don’t know if these portraits still exist anywhere. They were granted their patent for the system in 1927.62

During World War II, Blanche’s inventive mind came back to life. In 1941, she noticed how a single thread could bring a whole sewing machine to a halt. So Blanche proposed that balloons with long strings hanging from them be floated over or near a city threatened with bombings. The strings would get tangled up in the plane’s propellers, potentially bringing down the whole machine. She called it a propeller snare.63 It wasn’t approved until 1945 and as far as I know it was never actually used, but it’s an interesting concept. Spaced out correctly and flown high enough, these balloons could work, though there seems like a lot of risk involved.

Later, in 1967, Blanche and her daughter Evelyn worked out an antipollution apparatus of sewage systems at the toilet source.64 This was her third and final patent; It was approved in 1970, but it’s unclear to me how it works or if it’s ever been put into use.

Though those are her only 3 patents, Blanche’s mind was constantly creating solutions. When she and Oakes designed Borderland, she also designed a system of dams and ponds to help drain the 1,200-acre property.65 Some people also claimed that Blanche designed Borderland herself “after becoming frustrated with the architect.”66 I’ve only seen that noted in one place, however.

She also kept improving Borderland her whole life. She added a spring-fed swimming pool and began cultivating turkeys. Her daughter Pauline later wrote, quote, “I used to think that Mother was the happiest when she was moving water around. She built dams to make new ponds, and was just as likely as not to be wielding a shovel along with the men.”67 However a lot of these items also equally fell into disrepair when Blanche became too old to care for them. When she died, the pool especially became useless because, quote, “no one could figure out how to make the system work.”68

Late in her life, Blanche sat down to write a biography of her father. She was prompted by John F. Kennedy’s 1955 book, Profiles in Courage, which she felt painted her father as little more than a carpetbagger. Her book was published in 1964. Adelbert Ames: Broken Oaths and Reconstruction in Mississippi, 1853-1933 is an incredible work of biographical research. It’s also clear from it how much she admired her father. At one point she writes, quote, “Love and compromise were a form of Adelbert’s religion…He felt that courage is an attribute of faith.”69

When she was finished, she wrote to Kennedy with, quote, “characteristic insouciance,” requesting that he correct his book’s slander of her father in future editions.70 She quoted slanderous and incorrect articles about him in the Boston Herald to point out how frustrating it would be to have historians repeat such lies for the rest of history. He wrote her back, saying that he didn’t anticipate a second edition of Profiles in Courage, but apologized for the slight. 71

On July 29, 1949, Oakes Ames had a stroke. He survived for another 8 months, but he had terrible trouble communicating. He could read individual words but couldn’t comprehend sentences, but it seems like he could understand and answer when spoken to. He died on April 28, 1950. Blanche made him a bronze monument to cover his tomb, each side carved with incredibly accurate and beautiful orchids that he loved. The catafalque stands over both of them.

Blanche died on March 2nd, 1969, also of a stroke, surviving Oakes by 19 years. She was 91 years old. She is buried next to him in the cemetery of the Unitarian Unity Church of North Easton.

Unfortunately, Blanche and other female political cartoonists, like Lou Rogers, have largely fallen into obscurity today. In fact, Clark in her dissertation points out that Blanche’s slide into obscurity was, quote, “accomplished in a single generation, an instructive example of how women are written out of history.”72 I think we’re reclaiming their stories a little, but it seems to me that we have a long way to go.

Blanche’s artwork was moving and talented, and it seems like the only reason they were forgotten was because women’s political art has been dismissed by mostly male historians as unworthy of serious consideration. As Clark quoted from Alice Sheppard Klak, women’s political artwork, quote, “shed light on the discourse about women that took place…They show the depth and extent of American ambivalence, fears and hopes about the roles that women might play.”73 The work of male political cartoonists has been privileged over women’s, even when men were sympathetic to suffrage and made art in support of the suffragists. Clark points to Rollin Kirby’s political cartoons, which often featured a, quote, “slender little suffragist lady in feathered hat and fur collar, an ephemeral vision perched like a bird with her hands outspread atop the ballot box, no threat at all to the unchanging world of male dominance.”74 The vision of women by women was much different. Blanche Ames Ames’s artworks stand as some of the first realistic representations of “the new woman” in American popular media.

Nevertheless, artwork by Blanche is in the collections of Dartmouth, Harvard, and Columbia Universities, and her portrait of her father in his Union Army uniform hangs in the Mississippi State Hall of Governors.75 Her botanical art is not only preserved in Oakes Ames’ books but also at the Harvard Botanical Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Some of her work went on view last year in the Smithsonian exhibition Orchids: Hidden Stories of Groundbreaking Women.

That is the story of Blanche Ames Ames! I hope you enjoyed this episode. You can let me know your thoughts on Substack, Twitter, and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks discover the podcast.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Clark. My research assistant is Niko Angell-Gargiulo. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com If you’d like to send us something, you can send it to P.O. Box 27162 Los Angeles CA 90027.

Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

Ames, Ames Blanche. Propeller snare. United States US2374261A, filed September 5, 1941, and issued April 24, 1945. https://patents.google.com/patent/US2374261A/en?q=(Blanche).

Ames, Ames Blanche, and Adelbert Ames Jr. System of color standards. United States US1612791A, filed July 13, 1922, and issued January 4, 1927. https://patents.google.com/patent/US1612791A/en?q=(Blanche).

Ames, Blanche Ames. The Map Blossoms [Editorial Cartoon by Blanche Ames Ames]. Ink on paper. Woman’s Journal and Suffrage News, May 22, 1915. Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries. https://images.socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/items/show/130.

Ames, Blanche Ames, and Evelyn Ames Davis. Apparatus for antipollution of sewage systems at toilet source. United States US3488780A, filed June 14, 1967, and issued January 13, 1970. https://patents.google.com/patent/US3488780A/en?q=(Blanche).

Blanche Ames, Seated, with a Newspaper on Her Lap and Her Eyeglasses in Her Left Hand. Oakes Ames Leans on the Table beside Her. 1940.

Clark, Anne Biller. “My Dear Mrs. Ames : A Study of the Life of Suffragist Cartoonist and Birth Control Reformer Blanche Ames Ames, 1878-1969.” University of Massachusetts Amherst, 1996. https://doi.org/10.7275/D815-3055.

“Loefgrenianthus.” In Wikipedia. Wikipedia, May 7, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Loefgrenianthus&oldid=1153714204.

Massachusetts Historical Society: Object of the Month. “‘A Rash and Dreadful Act for a Woman’: The 1915 Woman Suffrage Parade in Boston,” July 2010. https://www.masshist.org/object-of-the-month/objects/a-rash-and-dreadful-act-for-a-woman-2010-07-01.

Metraux, Julia. “The Birth of the Modern American Military Hospital.” JSTOR Daily, May 29, 2023. https://daily.jstor.org/the-birth-of-the-modern-american-military-hospital/.

Peters, Janelle. “How Tea Helped Women Sell Suffrage.” The Atlantic, September 30, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/09/how-tea-helped-women-sell-suffrage/571546/.

Price, Karen, and Gail Davis. “Suffrage Cartoons of Blanche Ames.” League of Women Voters of Needham (blog). Accessed August 10, 2023. https://lwv-needham.org/suffrage-cartoons-of-blanche-ames-2/.

Simkin, John. “Blanche Ames.” Spartacus Educational (blog), September 1997. https://spartacus-educational.com/USAWames.htm.

Smithsonian Gardens. “Botanical Art and Illustration,” 2022. https://gardens.si.edu/exhibitions/orchids-hidden-stories-of-groundbreaking-women/botanical-art-and-illustration/.

Snyder, Laura J. “Brief Life of Blanche Ames, Intrepid Botanical Illustrator.” Harvard Magazine, June 2017. https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2017/06/blanche-ames.

Suffrage 100: MA. “Blanche Ames 1878-1969.” 2020. Commonwealth Museum. https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mus/pdfs/26-Ames.pdf.

Suffrage at Simmons. “Marching in Protest · The Women’s Suffrage Movement in a College Community · Suffrage at Simmons.” Accessed August 22, 2023. https://beatleyweb.simmons.edu/suffrage/exhibits/show/simmons-university-and-the-suf/marching-in-protest.

Trahan, Erin. “Massachusetts Suffragette And Birth Control Trailblazer Gets Her Due In A New Documentary.” Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.wbur.org/news/2020/02/20/documentary-borderland-blanche-ames-suffragette-activist.

Van Voris, Jacqueline. “Ames, Blanche Ames: Artist and Women’s Rights Activist.” American National Biography, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1500013.

“Woman’s Journal.” In Wikipedia, March 20, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Woman%27s_Journal&oldid=1145767155.

Just FYI, some of the links in here are affiliate links. That just means that if you click through and buy something, I will get a few cents in my pocket but it won’t cost anything extra for you.

Anne Biller Clark, “My Dear Mrs. Ames : A Study of the Life of Suffragist Cartoonist and Birth Control Reformer Blanche Ames Ames, 1878-1969.” (University of Massachusetts Amherst, 1996), https://doi.org/10.7275/D815-3055.

Clark, 6

Clark, 60

Clark, 53

Clark, 54

Clark, 56

Clark, 61

Clark, 6

Clark, 7

Clark, 7

Clark, 59

Clark, 88

Clark, 88

Clark, 89

Julia Metraux, “The Birth of the Modern American Military Hospital,” JSTOR Daily, May 29, 2023, https://daily.jstor.org/the-birth-of-the-modern-american-military-hospital/.

Clark, 93

Clark, 16

Clark, 16

Clark, 19

Clark, 96

Clark, 96

Laura J. Snyder, “Brief Life of Blanche Ames, Intrepid Botanical Illustrator,” Harvard Magazine, June 2017, https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2017/06/blanche-ames.

Clark, 10

Clark, 7

Clark, 114

Clark, 114

Clark, 109

Clark, 120

Clark, 124

“Botanical Art and Illustration,” Smithsonian Gardens (blog), 2022, https://gardens.si.edu/exhibitions/orchids-hidden-stories-of-groundbreaking-women/botanical-art-and-illustration/.

“Blanche Ames 1878-1969,” Suffrage 100: MA, 2020, Commonwealth Museum, https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mus/pdfs/26-Ames.pdf.

“Loefgrenianthus,” in Wikipedia (Wikipedia, May 7, 2023), https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Loefgrenianthus&oldid=1153714204.

Snyder

Clark, 11

Clark, 14

Clark, 172

Clark, 170-71

Clark, 8

Blanche Ames Ames, The Map Blossoms [Editorial Cartoon by Blanche Ames Ames], Ink on paper (Woman’s Journal and Suffrage News, May 22, 1915), Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries, https://images.socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/items/show/130.

“Marching in Protest · The Women’s Suffrage Movement in a College Community · Suffrage at Simmons,” Suffrage at Simmons (blog), accessed August 22, 2023, https://beatleyweb.simmons.edu/suffrage/exhibits/show/simmons-university-and-the-suf/marching-in-protest.

Janelle Peters, “How Tea Helped Women Sell Suffrage,” The Atlantic, September 30, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/09/how-tea-helped-women-sell-suffrage/571546/.

Clark, 11

Clark, 12

Clark, 205

Clark, 205

Clark, 9

Clark, 206

Clark, 207

John Simkin, “Blanche Ames,” Spartacus Educational (blog), September 1997, https://spartacus-educational.com/USAWames.htm.

Clark, 208

Clark, 214

Clark, 227

Clark, 227

Clark, 243

Clark, 230-31

Clark, 232

Clark, 217

Clark, 244

Clark, 241

Clark, 241-2

Clark, 244

Ames Blanche Ames and Jr Adelbert Ames, System of color standards, United States US1612791A, filed July 13, 1922, and issued January 4, 1927, https://patents.google.com/patent/US1612791A/en?q=(Blanche).

Ames Blanche Ames, Propeller snare, United States US2374261A, filed September 5, 1941, and issued April 24, 1945, https://patents.google.com/patent/US2374261A/en?q=(Blanche).

Blanche Ames Ames and Evelyn Ames Davis, Apparatus for antipollution of sewage systems at toilet source, United States US3488780A, filed June 14, 1967, and issued January 13, 1970, https://patents.google.com/patent/US3488780A/en?q=(Blanche).

Blanche Ames, “Blanche Ames 1878-1969,” Suffrage 100: MA, 2020, Commonwealth Museum, https://www.sec.state.ma.us/mus/pdfs/26-Ames.pdf.

“Blanche Ames 1878-1969“

Clark, 251

Clark, 251

Clark, 61

Clark, 254

Clark, 255

Clark, 256

Clark, 173

Clark, 174

Clark, 250

Share this post