Hey everyone!

I’m delighted to bring this next episode to your ears. Polly Adler’s story is a fascinating one of a woman determined to squeeze more out of life than everyone else was willing to allot to her. From abject poverty, she rose to dizzying heights of money and power in New York City and was often at the center of many of New York’s most interesting moments in the 20th century.

Enjoy!

🎙️ Transcript

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m going to be covering someone who makes Jay Gatsby look like a pretty tame fellow: Polly Adler.

She was a Russian Jewish immigrant to the US in the years before World War I. She seemed destined for a life of hard work and low wages, but she refused to live a life of poverty just because it was what was expected of her as a quote-unquote ‘good Jewish girl.’ Instead, she became a madam, running the best brothel in all of New York City for over twenty years. Her position as caterer of delights to America’s elite made her incredibly powerful behind the scenes, as we’re all about to see. She was famous around the US, and when she wrote her autobiography in the 1950s, it was a sensation. I’m so excited to tell you all about her. For a lot of this, I’ll be relying on the biography of Polly Adler by Debby Applegate as well as Adler’s own memoir, A House Is Not A Home.

A few quick notes before we hop in: First, a series of trigger warnings: Polly was Jewish and faced a lot of antisemitism especially early in her life in Russia, so I’m going to touch on that. Then, later on in her life, Polly and her fellow workers in the sex trade happily used the word ‘whore’ to describe themselves and their jobs. To use the words of Danton Walker, quote, “They were known…by the Biblical name: whores, and their establishments were called whorehouses.”1 I probably won’t use the word ‘whore’ that often, but it will come up. If either of those things bother you this may not be a good episode for you. And final warning, unfortunately with an unregulated industry like the sex trade and bootlegging alcohol comes unsavory things like murder, sexual violence, and general criminal activity. While I’m going to skip over most of the really gruesome bits, if you’re not into that, well, my feelings won’t be hurt if you don’t want to listen to this.

All right, let’s hop back in time.

Polly Alder was born Pearl Adler in 1900 in the Jewish Pale of Russia. Her actual birthdate is somewhat up for debate: Any records were lost to fire and war, and her parents weren’t quite sure either. Her mother, Gittel, was, quote,

Sure that her firstborn child was delivered on a Sunday two weeks before the Passover holiday, but the year—that Gittel didn’t know. Moshe, her father, was certain that Pearl was a year and a half old when the American president William McKinley was killed by that madman in Buffalo, New York…[so] Moshe settled on the seventeenth day of the month of Nisan in the year of 5660 by the Jewish calendar, or April 16, 1900.2

To reduce confusion, I’m going to go ahead and call her Polly for this entire episode, though she wasn’t given the new name until she had been living in the US for a few years.

In Yanow, where Polly was born and the family remained for many years, they were relatively well off, living in a big house with a yard. Moshe was a tailor and used the front room for client fittings, and his assistant and their maid-of-all-work lived in the back room. Polly’s mother split her time between helping Moshe with the business and taking care of the family–she gave birth to six boys and one more girl after Polly.

Moshe had wanderlust–he took a trip to New York City early in Polly’s life, which made him quite cosmopolitan. In Yanow, most people had never even left to go to the nearby city of Pinsk, let alone traveled to another country. Moshe would also visit Warsaw and Berlin during her childhood and would realize that there was a whole world outside of Yanow for his family.

In her autobiography, Polly wrote, “It seems to me that at a quite early age I began identifying myself with my father–if by identifying is meant preferring a role which would not confine my horizon to the boundaries of Yanow or limit my activities to cooking, sewing, scrubbing and childbearing… I wanted to get out and see the world and mingle with people and have my say about what went on.”3

This was easier wished for than done. In a small town like Yanow, a local boy might study in the yeshivas or travel for work, but the world was seen as dangerous for good Jewish girls, and it wasn’t considered ‘nice’ for her to want to leave. And even if that hadn’t been the case, an aggressively anti-Jewish bureaucracy in Russia made it incredibly difficult for her to do anything. She would have had to obtain an expensive legal permit to change residence and work or study elsewhere. Jews were forbidden to live in most parts of Russia unless they were considered “useful” in some capacity.4 According to Debby Applegate, who wrote the biography of Polly Adler, Madam, that I’m relying on pretty heavily for this episode, quote, “It was whispered that some girls were so desperate to go to school in Moscow or St. Petersburg that they agreed to register as “useful” prostitutes so they could get a special passport or “yellow ticket” that allowed them to live in the metropolis.”5 The Russian government very thoroughly regulated every aspect of a Jewish person’s life in the empire–and there were nearly 5 million Jews living in Russia. For the most part, they had been forced into specific communities, specific careers, and faced quotas for how many Jews could attend school or enter a profession– “legislative pogroms” as one journalist dubbed them.6

So, life in Yanow was not easy. While Yanow wasn’t an exclusively Jewish town, the Adler family lived in the Jewish neighborhood among other Jewish people. The town had its own caste system and accompanying snobbery: “The Hasidic Jews looked down on the merely orthodox, the Zionists railed against the socialists, the progressives scorned the traditionalists–and vice versa. Those who showed too much aspiration for their social station were ridiculed for putting on airs. Anyone who showed too much independence from the common wisdom of the community was sure to feel the last of gossiping tongues."7 And of course, quote, “once the townsfolk put someone ‘in their place,’ it was nearly impossible to break free of that identity.”8

Within this society, a woman’s worth was measured by her ability to help her husband live according to God’s law–women were not well-educated by today’s standards, but they did handle the family business and were usually at least more financially savvy than their husbands. They were discouraged from learning Hebrew and studying the Torah, but they often spoke Russian, Polish, and local dialects to help them in math and negotiation in the marketplace.

But Moshe was different. Polly’s most cherished ambition was to get an education, and he really supported her in this. According to Applegate,

He and [Polly] enjoyed a not-uncommon emotional dynamic, one that shaped the lives of many of history’s most accomplished women: a father who was unconventional but self-certain, frustrated in his own ambitions, and eager to channel them into his oldest child, even if she had the misfortune of being a girl. In turn, [Polly] had all the attributes of an eldest daughter who was treated like a son: confident, quick-witted, competitive, and determined to prove she was just as capable as any boy.9

Meanwhile, between 1907 and 1910, local governments in Russia began expelling thousands of Jews from their homes, driving the dispossessed into a small number of villages like Yanow.10 The overcrowding led to ruinous competition, lowering everyone’s standard of living; remember, Jews were restricted to working only in certain industries and so there quickly became too many shoemakers, tailors, blacksmiths, and shopkeepers.11 As more arrived, they found themselves becoming beggars, living in poverty.

Increasingly, Jewish parents became nervous. It wasn’t hard to see that their kids wouldn’t have a good future in Russia, and with increasing anti-semitic policies coming down, they began sending their children out of Russia to continue their education elsewhere. Polly was determined to be one of the ones that got out: “By the time I was twelve, all my hopes and plans for the future hinged on my winning a scholarship to the Gymnazia at Pinsk,” she wrote.12

She began studying with the local rabbi with Moshe’s blessing–and money. While other fathers scoffed at a daughter receiving such a dedicated and intense education, Moshe paid the rabbi to prepare her for the entrance exam, which included studying the Russian language, Hebrew history, and math.

While we know that this education paid off in uncounted ways, we don’t know if Polly would have received the scholarship she desperately craved, because by the time it was awarded, she was well on her way to America. The latest round of anti-Semitic decrees had made it clear that remaining in Russia was out of the question, so Moshe began planning for their escape. When he heard that one of their cousins was sailing to the US, Moshe decided Polly would accompany her.

If you’re surprised he didn’t try to move the family as a whole–consider the cost. A single ticket cost about forty US dollars, and most Jewish emigres had to pay a quote-unquote travel broker–what we’d call now a human smuggler–an extra fee to shepherd them safely to the seaport because they legally couldn’t travel.13 In addition to whatever the smuggler pocketed, each traveler had to give him enough to cover all their necessary bribes and accommodations along the way. Finally, each emigrant was required by US law to have twenty US dollars in hand when they arrived, to ensure that they would not become beggars or thieves. I’m guessing a little here, but the total cost to leave might have been, what, a hundred US, at minimum? In 1913, when Polly traveled, a hundred US dollars was equivalent to about $2,800 now. Multiply that by the two parents and eight total children, and we’re talking about $28,000 today. That wasn’t something the family could save up on short notice. So yeah, they sent Polly alone to establish a foothold and then she would send for them when she was able.

That said, the US government didn’t… love this habit of sending young teenage girls alone to America. In 1913, the same year that Polly immigrated, they mandated that no unaccompanied girl under the age of sixteen could be legally admitted into the US. According to Applegate, this rule was “routinely broken.”14

When we talk about most immigrants moving to the US, it was traditional for a husband or older son. But for Jewish people in this period, it was expected that women would shoulder worldly responsibility at a young age–we did just talk about how wives would handle family business while husbands focused on faith. So sending a teenage girl, for a Jewish family, was perfectly reasonable. Teenage daughters were, quote, “commonly the first in their families to travel to America, where they would live with friends or relatives while they saved enough money to pay for their family’s steamship tickets.”15 So when Polly arrived, she was just one of a huge number–“13,588 unaccompanied Jewish girls” who came through Ellis Island in 1913.16

In her autobiography, Polly told the story of the first adult decision she ever made on the way to the US. After passing through the treacherous tunnels and the bureaucratic hoops to board their ship in Germany, her cousin got scared and backed out. She was too afraid to move to a strange country, and begged Polly to ask for permission to go back. As an adult, she recounted,

When I saw it was useless to argue with her, I made my first adult decision. Let my cousin go back; I’d go on! I went over to the emigration officer, turned on the tears, and talked him into giving me a re-entry permit–one only. Then I marched back to my cousin, thrust it into her hand, and told her of my determination to go on to America. Though she put up a token resistance, the one thing on her mind was getting the hell out of there and back to Russia, so it wasn’t long before she kissed me good-bye.17

When she landed, she was bundled onto a train to Springfield, Massachusetts, where her father had some friends from the village. It was a weird choice–they had family in New York and Chicago, and both cities had large Jewish communities, which Springfield did not. But that’s where he chose. When she arrived at the station, there was no one there to greet her. A stationmaster assured her someone would be there soon and gave her a piece of candy, but she remained scared. When it got dark and big electric signs turned on, Polly was petrified, because she’d never seen anything like it before.

The Resnicks shared an odd relationship with Polly after she came to live with them. They fed and clothed her but were largely uninterested in her otherwise. They sent her to school as soon as she arrived, in an evening program for, quote, “Illiterate Adults.”18 However, once she had met the basic educational requirements for immigrants–which at that time was a fourth-grade mastery of the English language–Mr. Resnick told her she had to get a job. It took some finangling, including a signed affidavit from her father in Yanow which lied that Polly was sixteen years old. She quickly found work at a paper factory, but it was repetitive and boring, with no chance to move up the ladder. It was a five-and-a-half-day work week, working from 6:30 am to 6 pm, and she only earned $3 a week, which was a low wage even then. ($3 week in 1914 would be $83/week now, or about $4300/year.) Most of her money went to the Resnicks for room and board, leaving her only pennies to spend and no room to save.

Polly was, of course, crushed. She had left her family and risked everything only to be a second-class citizen, “doomed to spend her days in a backbreaking struggle for food and shelter.”19

While it probably wasn’t her father’s intention, Springfield was a great place to become Americanized. The city had one of the best education systems in the country, and girls were allowed to join clubs, play sports, act in plays, and attend concerts, dances, and movies.20 The city was also a melting pot of several immigrant groups–Polly’s earliest friends were two Irish-American girls who lived next door.21

Now, family lore has it that sometime after she graduated in March 1915, Polly was caught walking hand-in-hand with a Christian boy.22 This was unacceptable–the Resnicks had not assimilated so much that a girl living under their roof could mix with non-Jewish people romantically. Shocked by this behavior, they declared her dead to them and even sat shiva, the ritual period of mourning, as if she had literally gone to the grave.23 They didn’t kick her out, but she might as well have been a ghost walking about in their midst.

So she left and moved to Brooklyn, where she hoped there was more than stony silence and a terrible job waiting for her. She moved in with a cousin, Breina Freedman, who welcomed her warmly. Breina would go on to provide a home for many of their shared family members when they first landed in America. They lived in a neighborhood called Brownsville, which had a reputation as, quote, “New York’s rawest, remotest, cheapest ghetto.”24 Almost a hundred thousand Jews lived in a space of only two square miles–it was the largest concentration of Jews in America and referred to as “the Jerusalem of America.”25 Large families often lived in one or two-bedroom apartments without bathrooms; baths had to be taken in tubs that were also used for laundry in public bathhouses. Apartments were so cramped and badly ventilated that they were freezing in the winter and sweltering in the summer. It wasn’t uncommon to see people sleeping on roofs and fire escapes.

By the time Polly arrived, Brownsville rivaled the worst cities in America for crime. Boxer Sammy Aaronson, who was also from Brownsville, later said, “Everyone in Brownsville who grew up honest did it by mistake.”26 Even when crime wasn’t the issue, immigrants watched their kids eschew Jewish traditions and become obsessed with the pursuit of money. They saw it as, quote, “a particularly powerful tool that helped them to transcend–at least compensate for–the barriers imposed by bigotry” and anti-Semitism.27 “Your money is as good as anybody else’s money, and it doesn’t come fairer than that, or more democratic,” once said reporter Michael Herr.28

She quickly found a job at a corset factory, which paid five dollars per week. That’s about $100 per week today. It’s low pay like this that made minimum wage laws become necessary starting in the 1920s. Though the pay was low, the work was steady and workshops were clean and safe thanks to a strong union representing the seamstresses. But her expenses were high compared to her pay: She paid $3/week for room and board, plus $1.20 per week on transportation and food expenses; that left less than $1 per week for all of her clothes, toiletries, and other necessities.29 Plus, the work was backbreaking. She would be bent over a needle six days a week for nine to ten hours a day, surrounded by the constant deafening racket of the sewing machines echoing in the factory.

At the factory, Polly made friends with a girl named Eva, who introduced her to American teen culture. The other girls at the factory, quote, “provided a thorough education in American ways, practicing English by singing ragtime song lyrics, gabbing about clothes and the stories theys aw at the nickelodeons, sympathizing over old-fashioned parents and newfangled men.”30 End quote. Eva got Polly to go out dancing with them, though Polly had been warned several times not to go to clubs in New York because of the risk of being kidnapped and trafficked by, quote, “white slavers” as human traffickers were sometimes called then.31

Though hesitant at first, Polly loved the world Eva introduced her to. Women didn’t need to be chaperoned at the halls, and so it was a heady taste of freedom. Brownsville was known as “the place to go” for both ragtime music and cocaine, so the dance halls were always wild and attracted folks from all over the city. “It was also my debut on the dance floor, and after five minutes I was convinced that was where I wanted to spend the rest of my life,” she wrote in her memoir A House Is Not A Home.32 Polly practiced dancing as often as she could and began entering dance contests around Brooklyn. She won prizes of candy, dolls, and even cash.

Soon after discovering the world of dance halls, she started going to Coney Island, known as “Sodom by the Sea.”33 Basically just a spit of land at the far end of Brooklyn, Coney Island was a place someone could go to, quote, “drink, gamble, have their palm read, watch a prizefight or a burlesque show as well as have their pockets picked, nose punched, and clothes stolen.”34 Waiters often doubled as pimps, and entertainers were openly gay and often worked in drag, which was riskier to do closer to Manhattan.35 Polly adored Coney Island and her photo album were filled with snapshots of her and her friends out there.

Even though Coney Island activities were cheap, 5 cents here, 10 cents there, it still added up. Since men earned twice as much, or even more, than women at the time, women relied on men to pay their way for these amusements. Polly and her friends called it “treating” but it could be cynically thought of as dating; it was “sexual barter: pleasure exchanged for pleasure–the treat of a day at Coney Island, a little present, an ice cream soda…exchanged for the charm of feminine company and the potential prospect of some kind of sexual intimacy.”36 I say cynically because it became something of a competition between the women; a reporter recorded two girls reflecting on their day in terms of how much money men spent on them. One said her day was great because, quote, “he blew $5” on her, whereas the other man was a, quote, “chump [who] only spent $2.55.”37 For some, it became a game to see “how much they could get in exchange for how little they had to give.”38 Pre-marital sex was often too big a risk, as an out-of-wedlock pregnancy was still disastrous for a woman’s reputation, and women didn’t want to be known for openly trading sex for money, but everything else was on the table.

And of course, the US entry into World War I only encouraged a loosening of morality, especially in Brooklyn where a lot of soldiers and sailors were deposited while waiting to be shipped to the war front. Rates of premarital sex jumped drastically in part because young women felt patriotic sleeping with soldiers before they went to war. Dubbed “victory girls,” they saw themselves as providing aid to men facing death and of course, these hormonal seventeen-year-old boys who had been drafted encouraged this belief by saying things like, “We are fighting for you girls, and you ought to do something for us.”39 Rates of STIs, illegitimate births, and elopements all rose “precipitously” in 1917.40

But Coney Island would end up being a site of serious danger for Polly. As we’ll talk about more in a few minutes, she had begun working at a factory making army uniforms, and she developed a crush on the foreman there. On a weekday afternoon during the winter, he invited her out to Coney Island; unbeknownst to her, the place was basically abandoned at this time. He locked her in a rickety house, beat her, and raped her. When she realized she was pregnant a few weeks later, he laughed in her face and refused to help pay for an abortion. She scraped together $35 for an abortion at a clinic in Brownsville; abortions were illegal at the time, but so were condoms and birth control hadn’t been invented yet, so there were a lot of doctors willing to perform the procedure. ($35 sounds cheap, so I want to point out that that’s equivalent of $829 today.) When she told the doctor what happened, he kindly charged her only $25 and told her to use her last $10 to buy some warmer shoes.

Polly, by this point, was 17, and her family was encouraging her to start thinking seriously about marriage. Especially because the, quote, “time-honored way to calm a wild-haired girl was to find her a husband.”41 They didn’t know about the attack by the foreman, but Polly was running with what they considered a wild crowd. While girls of her generation saw a wedding as The Goal, capital T, capital G, it was often a little fraught. Respectable wives didn’t work outside the home, but families in Brownsville could not make ends meet on one salary. And even if they found husbands with good jobs, marriage wasn’t a luxury. For most women, it was an endless cycle of pregnancy and childbirth and housekeeping. It’s hardly any surprise that many girls of this generation started postponing marriage as long as they could.

So instead of thinking about marriage, Polly began pursuing money for herself. She developed a love of finery, or as much finery as she could afford on less than a dollar a week. She and her friends were, quote, “paragons of working-girl fashion, sporting impractically high French heels, daring skirts that showed off the ankles, and girlish empire waistlines that dispensed with the hourglass corsets that made it impossible to dance.42 In fact, Polly remembers curvy figures as being “out of style and the boyish figure all the rage.”43 She, however, was naturally curvy so she bound her chest with strips of white cloth to make herself “as flat in the front as possible.”44 She sometimes bound these so tight that she nearly passed out of her machine at the factory, and didn’t stop until her coworkers began relentlessly calling these bindings her, quote, “mummy wrappings.”45

Of course, all these clothes she wanted were expensive. Even a really cheap store-bought dress at the time would cost more than $5, so Polly used her sewing skills to make her own clothes. She modeled her look on Theda Bara, the star of the 1915 blockbuster A Fool there Was. Bara popularized the Vamp look (though its origins are in an 1897 painting called The Vampire).46 The Vamp was a new archetype of femininity, it’s the origin of the femme fatale, women who were unashamed of sex and used it as a tool as much as men did. Polly, ambitious and ready to throw off the rules that had already shamed her so much in her short life, embraced this wholeheartedly, calling herself a “baby vamp.”47

During the war, Polly’s job at the corset factory ended because the metal needed for women’s corsets got diverted into the war machine. She found another job making men’s army uniforms, this one making $10 a week, which was about $200 a week in today’s money. Nevertheless, she found herself “restless and discontented…thinking that surely life must offer me other alternatives than a factory job.”48 She also began to crave moving out of her cousin’s home, where she was still sleeping on a couch. When the armistice came, Polly’s job ended once again, and she knew it was her chance. She went to the Tenderloin with her friend Eva to begin looking for a new job and cheap apartments when they coincidentally met a young musician named Harry Richman who was on the up and up. Eva ditched them so Polly and Harry passed the evening in in Bal Tabarin, a new supper club and cabaret inside the Winter Garden Theater, named for the famous bar in Paris. They stayed out all night, and though Polly claimed in her memoirs that the evening was innocent when she got home the next morning her cheap clothes were in tatters and she was clearly hungover. Her cousin kicked her out immediately.

Standing on a subway platform with her meager possessions wrapped in a bundle of newspaper, Polly burst into laughter. In her memoir she said, quote, “So far, I had certainly racked up a row of goose eggs in the Golden Land. I had failed in my quest for the education I might have gotten in Pinsk, I had lost my virginity, my reputation and my job. All I had gotten was older.”49

She set her sights on Manhattan, where everyone came lured by dreams. Rent had skyrocketed due to wartime inflation, and there was a housing shortage besides, because demobilized soldiers and sailors were arriving back on US shores. She eventually found something in the Gashouse District, near Union Square, named for the towering gas tanks that lined that stretch of the East River.50 The stench of the gas often blew through the streets, which must have been vile. The neighborhood’s main claim to fame was its particularly violent street gangs.

But she still hadn’t found a job. She searched for weeks–she’d spent all her savings on the apartment’s first month’s rent, and was starting to worry she’d never find anything. That’s when she met Abe Shornik, another Russian Jew who had immigrated to the city. They met one of the many cafés around the neighborhood that served, quote, “respectable patrons during the day but because the hangouts of the city’s underbelly when decent people were in bed.”51

Polly eventually landed a job at the Trio Corset Company in January 1919. She started just days before twenty thousand seamstresses turned off their machines and walked out of work to begin the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union’s strike. It would end up lasting three months. For Polly, the strike was a disaster because she had no family and no savings to fall back on; it’s unclear how she made money or paid rent during it. And even when it ended, things didn’t get easier–just the next month, the May Day Massacres set off a summer of strikes around the city, including the scrubwomen at the Mutual Life Insurance building and actors’ union on Broadway–the result was less demand for corsets and women’s clothing from employers and theaters, meaning Polly and her coworkers still struggled. Again, how she managed to keep paying rent during 1919 is unclear, though it’s probable that this is when she turned to prostitution herself. Though she would later be very forthcoming about any number of subjects, the year 1919 is one she was always cagey about. “I had to be a madam, I was never pretty enough to be a hustler,” she would say; hustler was a common euphemism for prostitute then. She was quick to point out, quote, “It was a hell of a life, but–as I hasten to point out before everybody else does–no tougher for me than for plenty of other poor working girls who didn’t become madams.”52

By the end of the year, she went to Abe Shornik for help. He took her uptown, to the wealthier West Side, where she met an aspiring singer named Joan who needed a roommate in this enormous apartment while her parents were out of town. Briefly, Polly reveled in this golden world she’d never had a glimpse of, but she began to see the reality soon. Joan had an opium addiction that she barely hid, and when her parents returned they turned out to actually be a pimp about their own age. Though the neighborhood had a veneer of respectability, the brownstones were, quote, “hived with hustlers and gimme girls of every variety, from freelancing roommates who picked up sailors on leave to elaborate harems that catered to the carriage trade. Almost certainly Abe Shornik brought her to some kind of discreet brothel.”53 For those in the know, the Upper West Side was “the district of loose women,” some five thousand of them according to the notorious morality police, the Committee of Fourteen.54

While some quote/unquote “good girls” might have balked, Polly was not put off by that. She was ambitious enough to see that the money was easier than backbreaking work in a factory, and the money brought a level of glitz and glamor to it that she’d been missing in Brownsville and the Gashouse District. The parties were raucous, filled with jazz, drugs, and sex.

Through Joan, she became friends with several Broadway dancers and singers, many who she’d keep in touch with throughout her career. For girls like Polly, Broadway was a dream because it was one of the few places that was equally welcoming to women and Jews as it was to Christian men. Not just in the theaters though–Broadway was known for having a seedy underbelly of gambling, fencing stealing goods, drug dealing, and prostitution.

A lot of these girls supplemented their earnings by being mistresses to wealthy men. From them, Polly learned that the key to an amicable ending to these relationships–because they always ended–was to persuade the man to, quote, “skip the flowers and chocolates and trinkets, and to give gifts of hard assets. Real estate or stocks and bonds were best, but furs and jewelry were welcome too.”55 Basically anything that could be liquidated for cash when the relationship ended. Women who spent their youth as mistresses that didn’t do this found themselves poor in their older years, eventually turning to prostitution when they weren’t young and attractive enough to play the mistress role anymore.56 These quote “gold diggers of the 1920s” particularly favored gold art deco bracelets studded with gems; they called them their “service stripes.”57

In the midst of all this came Prohibition. The Eighteenth Amendment passed on January 16, 1919, prohibiting the production, transport, and sale of liquor, poised to go into effect a year later. As the date approached, the mood on Broadway turned gloomy. Many places stocked up on liquor to try to carry them into the ban, but it would only last so long. Most restaurants and theaters were terrified of how the ban would impact business, sure they would go under.

Of course, we know what happened when the ban went into effect. No one stopped drinking, they just changed how. In New York City, the 10,343 licensed bars of 1919 were replaced by more than fifteen thousand speakeasies by February 1920.58 Which, really, should come as no surprise. All the vice trades–alcohol, prostitution, drugs–have survived countless moral crusades and they will continue to, and banning it always always is a financial boon for criminal classes and a financial stressor for governments.

And Polly was perfectly poised to take advantage of this. Also through Joan, she had befriended someone named Tony, a bootlegger who would grow up to be a well-known gangster. At the time, he was having an affair with a married woman, so he told Polly that if she would keep an apartment where he could meet his lady friend whenever he wanted, he would pay the rent. In her memoir, Polly wrote, “It never even occurred to me to think of Tony’s plan and my part in it as being moral or immoral. It did not touch me personally. It simply paid my rent. I didn’t think Now I’ll be a madam and run a house of assignation… I’m not apologizing for my decision, nor do I think, even if I had been aware of the moral issues involved, I would have made a different one. My feeling is that by the time there are such choices to be made, your life already has made the decision for you.”59

With Tony’s money she moved into an apartment on West 115th street, in a neighborhood called Morningside Heights, feeling a bit like she had finally made it. When Tony’s romance fell apart, he asked Polly to find a new girl for him, so she called up a girl who she knew, quote, “made no bones about…being available for a fee.”60 Tony gave her fifty and the girl a hundred, and Polly was officially a madam, though I don’t think there was any real paperwork involved. She began making a hundred dollars a week just from Tony, which today is over $1500. She was making four times the average white male workers salary at the time!61 All along, Polly had been sending whatever money she could spare back home to Yanow, and now she began to send more. She told her parents she was managing a corset factory.

Once she had extra money, Polly spent it glamming up her wardrobe and going out around Broadway. She met more men looking to meet girls, and she met more girls willing to go on a date, maybe more, for a decent fee. Moreover, the apartment was directly across from Columbia University, my alma mater, but back then it was all-men’s university, which both lent an air legitimacy to the area, but also made sure there was a constant supply of new clients with money. Barnard College was also right around the corner, and to most people the 22-year-old Polly passed for Barnard student!62 Her neighbors suspected nothing; they just thought she was a well-to-do girl studying at school and partying most nights. Her new job didn’t trouble her; as she reflected later, quote, “I didn’t invent sex, nobody had to come to my apartment who didn’t want to.”63 She never forced the women to be there, they were paid well, and they went home at the end of the night, unless they didn’t have anywhere else to go.

Actually, it’s worth noting that Polly was careful to treat these people as employees and investments, not as a commodity that could be beaten and stolen from, which was how male pimps tended to treat prostitutes. Smithsonian Magazine noted that she had a habit of, quote, “teaching the coarser ones table manners and encouraging them to read, reminding them that they couldn’t stay in “the life” forever. She never had to advertise or lure potential ‘gals,’ but instead turned away thirty or forty for every one she hired.”64

The first time Polly was arrested came just a few months later. Though the case was dismissed, she felt that she was at a crossroads: She could accept this was her life and embrace being a madam by doing it in a businesslike way, or she could give up the life and go back to factory work for $10 a week. Obviously, she decided to pursue it like a business, or we wouldn’t be here today, but she still viewed it as, quote, “a temporary expedient…I’d quit when I had enough capital to finance a legitimate enterprise.”65

She found that managing a brothel was busy work. Not just drumming up customers and workers, but she was also keeping the place clean, bringing in food and illegal alcohol, bringing in musicians. Polly had decided that if she was going to do it, she was going to be the best at it, and her “house,” as they were called, got a good reputation as a place where people would party and spend an entire night. She was so busy that major changes, like women getting the vote, didn’t even register on her radar; “I was too busy running a house to spare a thought to running the country,” she wrote.66

It became an adage that, quote, “Jewish women made the best madams.”67 It was a belief backed by numbers: 20% of New York’s population was Jewish at the time, but they owned 50% of the city’s brothels.68 And it was actually thanks to the village heritage I talked about earlier–girls were taught how to run a business from a young age while boys studied the Torah, remember? They learned the two main skills necessary to run a house: Good financial skills and how to entertain.

Within two years, Polly had saved up six thousand dollars, which is a little over $108,000 today. She and a friend called Neddie decided to pool their resources and open a lingerie shop on Broadway. Polly designed the clothes and Neddie handled the books. But by this time, the cops had Polly’s number and couldn’t believe she’d turned legit; they arrested her and Neddie and dragged them downtown. When they produced evidence that it was a legitimate store, the case was dismissed, but it must have seemed foreboding.

Polly’s Lingerie Shop was not a success. They held on for about a year, just barely breaking even. The timing was good though, because it was while the shop was open that her father arrived in New York. Though Polly never felt much shame about being a madam, she’d worried about her parents’ reaction if they knew; having a legitimate business allowed her to face him. Her apparent success heartened him, and he bragged to her cousins–who had written to him when they kicked her out of Brooklyn–that they had been wrong and his daughter was a success. Polly even told him she was engaged to a rabbi’s son, though that part was a complete lie. He went back home to Yanow convinced he had made the right decision in sending his daughter to the US.

After about a year though, the lingerie shop had to close, and Polly went right back to being a madam. With only a hundred dollars in her pocket, she went to Arnold Rothstein for start-up capital. Rothstein, was known as A.R. to his colleagues, a nod to the fact that he was the criminal underworld’s J.P. Morgan–a short-term banker for the underworld. He had legitimate businesses in insurance and real estate, but in Polly’s world, he was primarily a fixer, racketeer, and crime boss, accused of fixing the 1919 World Series. He was also partial to women in general, both in terms of keeping several mistresses as well as a beautiful wife, but he also believed that women made the best jewel thieves, and were key to any successful racket. He was known to invest heavily in brothels, and so Polly went to him for a loan to get back on her feet. To make sure she could pay it back, he let it be known that her house existed and was recommended by A.R.--very soon she was running a busy house again, this time with a clientele of primarily gangsters, hoodlums, and bootleggers, “some of whom were to become the big shots of the day.”69

In her brief absence, the flapper girls had popularized–which, by the way, the flapper phenomenon is probably what I’m going to cover in the bonus segment for this episode. And while a lot of people denounced flappers as a morally bankrupt generation of women, they also sort of thought that the rise of the flapper would put madams like Polly out of business. Because, quote, “why would a man pay for sex when the city seemed to be teeming with amateurs eager to jump into bed for free?”70 But the same people who considered Prohibition a bad bet, knew that prostitution would survive. Polly called up the people she knew from before, telling them she was back in business, and things continued right along. She built up a network of “go-betweens”--waiters, bartenders, busboys, elevator operators, and cabbies, anyone who might be in the right place at the right time to point a man in her direction for a small commission.

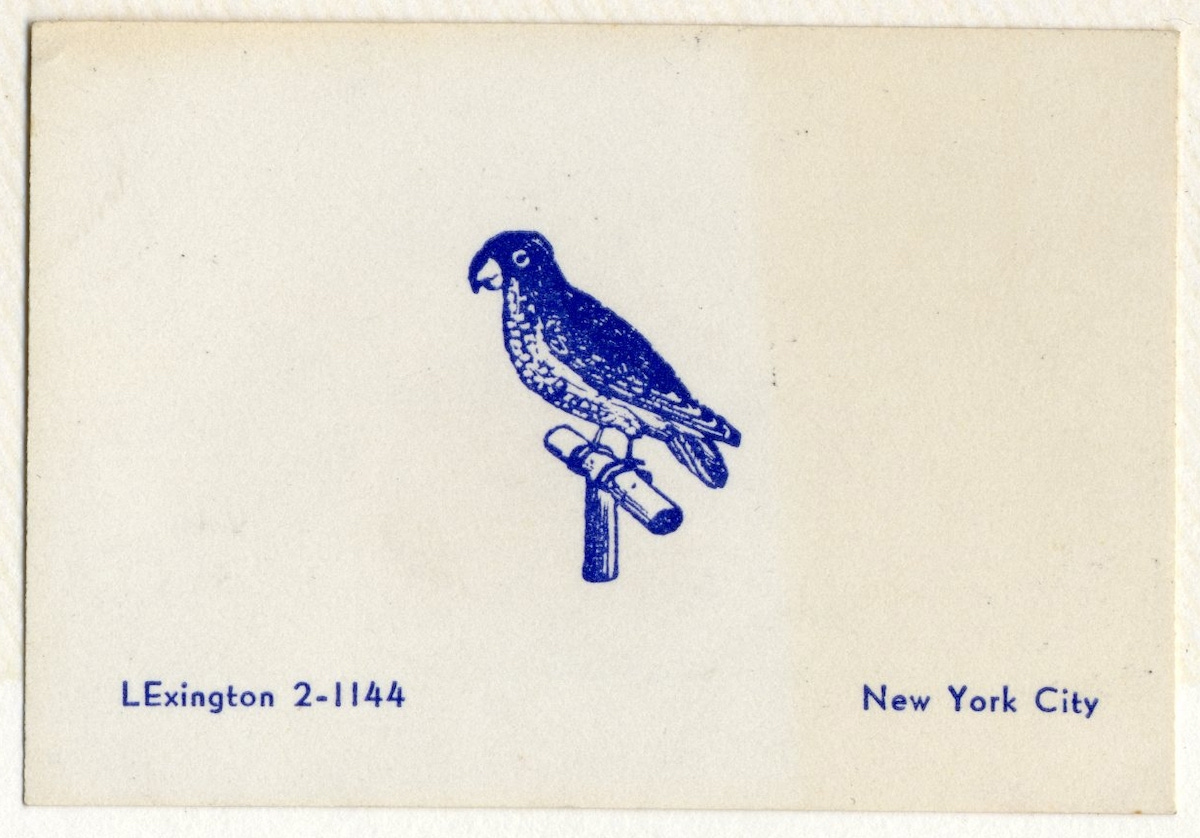

Luxury hotels, by the way, were the best places to do this. Unlike in The White Lotus, where the hotel manager is annoyed by Lucia and Mia hanging around the lobby, hotel managers turned a blind eye to this at the grand hotels like the Biltmore, the Waldorf Astoria, et cetera. “As long as they were discreet, well dressed, and tipped generously,” the girls were welcome because it meant the guests kept coming back.71 In some hotels, the staff handed guests a card to give to the madam, which signaled that the madam was not to bill the guest directly but to bill the hotel, and they would charge the guest using a discreet line item on the hotel bill.72

But while hotels were helpful, the Vice Squad cops made life hard. Several were as corrupt as the people they arrested. The squad ran a shakedown operation of madams and gangsters that brought in millions of dollars annually. According to Adler’s biographer, Debby Applegate, quote, “The stream of graft from vice was so steady and so lucrative that it required excellent political connections and a kickback of several thousand dollars to wrangle a spot on one of the plainclothes squads spread throughout the city.”73 Professional lawbreakers like Polly had mixed feelings about the system; on the one hadd she began paying hefty bribes to cops to look the other way; on the other hand, without crooked cops all the black markets in New York would close up eventually.

The bribes really added up though. During one of her arrests, a bail bondsman showed up and offered to put up bail to release her, but he said that if she used a lawyer he recommended, quote, “he could guarantee the charges would ‘go out the window.’”74 Either the charges would be dismissed for lack of evidence or she’d be acquitted, but the fee was anywhere from $200-$500.75 Of that, $25 went to paying the arresting officer to either not show up or make such a huge mess of his testimony that the charges had to be dropped. Sometimes the judge was also in on it, and so he or she would get a cut. Whatever was left went to the bondman and the attorney. If she refused, she was guaranteed a guilty verdict and time behind bars; her choices became “go to jail or go broke.”76

Of course, once they’d found a mark, the police would target the same people over and over again. Let them build up their savings just enough, then make an arrest to drain it. Polly tried to outrun them by changing apartments frequently, but they always caught up. Madams had ways of trying to counter this, and they shared tips and tricks with each other. One got photos of plainclothes detectives quote, “at work and at play” which she used to blackmail them right back; she kept the negatives in a safety deposit box.77 Polly learned to identify the thick-soled black shoes that were too ugly to be stylish; the cops needed them for all the walking they did all day.

Soon though, George McManus, the famous Broadway oddsmaker, found her house and decided he liked it. He was the son of an NYPD officer, tall, goodlooking, and charming. He was known as “Smiling George” and beloved by everyone in the service industry because he had a habit of dropping twenty-dollar tips without blinking.78 He and “Big” Bill Dwyer were running the hottest secret craps game in New York city, with “action running as high as $700,000 some nights.”79 $700,000 in 1923 is 12 million dollars today. When the game was done and everyone had collected their winnings, Smiling George would cart a few players with him to Polly’s, where they were guaranteed to be safe from muggings by sore losers. She found that, quote, “there was nothing like craps to stoke the appetite for a playmate…compared with the quiet concentration of cards…craps was a glorious circus, noisy, fast, and surging with adrenaline at each roll of the dice. Here women were considered good luck and were often asked to kiss or blow on the dice. Players could multiply their winnings in minutes, as much as 900 percent in just two rolls–an aphrodisiac if there ever was one.”80

“Money meant nothing to those fellows; they sometimes spent five hundred or more in an evening. Whoever won the crap game payed the bill.”81 At their encouragement, she began selling alcohol too, encouraging men to come over earlier and stay later. Soon, her bar bills “dwarfed her profits on the bedrooms.”82 She was still careful with money, so for a while she was bartender and host, paying only the girls and a single maid to keep the home clean. She quickly gained a reputation of having a comfortable “speakeasy with a harem conveniently handy.”83 As Applegate put it, “In a world of villains, she became known as someone a villain could trust… [someone with] real brains, sharp instincts, and moxie.”84 Importantly, she still spoke perfect Yiddish, the lingua franca of the Jewish underworld, which was very useful for evading the predominantly Irish NYPD.

Polly still had ideas of eventually going legit again, but she had leaned into the idea of being a madam for a while longer and allowing herself even more luxuries. She had always enjoyed them, of course, but now she was really going for it: She was saving up for a mink coat, a very pricey object indeed. She talked about it all the time, to the point that, quote, “when a guy was trying to make a point at craps, he’d holler, ‘Come on, little Joe! This is for Polly’s mink coat.’”85 To tease her about this dream, johns would ask her, “how’s trapping tonight?”86 When she finally got her first, she, quote, “instructed the furrier to let himself go, even if it meant decimating the mink populations of the world. I didn’t care how big and bulky the coat was, I wanted to be swathed in mink, dripping it, trailing it.”87

It wasn’t all fun and games though–we are talking about violent criminals, after all. Polly noted in her memoirs that the gangsters treated the prostitutes worse than the legitimate businessmen she had coming in did; in the criminal underworld, women were second-class citizens and prostitutes were on the lowest rungs of the ladder. Racketeers frowned on a man who got serious with a prostitute, and one girl working for Polly was punished–Polly uses the word “mishandled,” which seems to imply raped–by the gang when she began dating one of their members seriously and stopped working.88 Nevertheless, he married her and got her out of the brothel; when he died she married someone working in a legitimate business and did well for herself. We know this because Polly was good about keeping up with the girls that worked for her, and tells their stories alongside her own in her memoirs. It seems that she would see them around long after they left her brothel and usually they all had a kind smile for each other.

After this traumatizing incident, Polly moved offices to a ten-bedroom apartment on 80th Street, a section of the Upper West Side populated by prosperous garment manufacturers, real estate investors, and financiers. The building was known as a safe one for vice entrepreneurs; the landlords didn’t mine leasing to madams, gamblers, and anyone else willing to pay an exorbitant rent for a little extra privacy. She was making enough money to do so, after all, and to buy a nice car as well.

She hadn’t planned on the aggressive competition though. There were several well-established houses in the area, and the madams didn’t take kindly to a youngster encroaching on their territory. They made complaints about her to the police, then when that didn’t do anything, they began sending hearses to her apartment on busy nights. As the party was really ramping up, “a couple of lugubrious characters would appear at the door with the announcement that they had come for the body.”89 To avoid unwanted attention, she began changing apartments very frequently, later earning the reputation that she changed apartments every 24 hours. Of course, this was hardly conducive to building a regular clientele, so she set out to make friends with her competition. She charmed them, convincing them to at least leave her alone, and settled down on 75th Street for a while.

This was her most luxurious house yet. She hired a decorator and, quote, “Aside from the traditional brothel décor—gilded mirrors and oil nudes, Louis Quinze competing with Louis Seize—Adler had a few signature touches, including a Chinese Room where guests could play mah-jongg, a bar built to resemble the recently excavated King Tut’s tomb” and more.90 Polly started to be called the Jewish Jezebel.

The new digs were safer, but the payouts were lower. Bankers and real estate moguls might have the money to be a regular client, but they weren’t down to party all night, so her bar tabs were much lower. She shifted to smaller apartments uptown, where women could meet clients for private dates, but she moved her main operation back down to the heart of Broadway, near Times Square; it was the area that author Raymond Chandler famously said was “a nice neighborhood to have bad habits in.”91

Soon, her girls “were known to be the best-looking, best-dressed and best–well, best all-around in New York.”92 Her goal was to have the expression “‘going to Polly’s’ [become] a euphemism for the world’s most popular indoor sport.”93 To do this, she began putting in appearances at clubs, bringing the prettiest girls that worked for her with her. “Soon there was a whole file of Polly Adler jokes which the emcees would haul out and dust off when we made out center-door fancy entrances,” she remembered.94 She might easily spend $500 in a night, but it was worth the investment–being out at the clubs was the equivalent of a good shop window display for her business.

This was how the 1920s continued for her. She became known as the best madam in New York City, as well as one of the most expensive. It’s rumored that many female Broadway stars worked for her before they made it big on the stage, because they could make a month’s rent on a single date. Many of the city’s most rich and powerful ended up on her doorstep more than once, including Mayor Jimmy Walker.

More notably, it’s said that Franklin Delano Roosevelt was one of her clients. Polly counted many very powerful men among her customers because she had a reputation not just for the prettiest girls and the most luxurious, but for keeping secrets. Whatever men preferred, or confessed in pillowtalk, never left her house. If she caught her employees selling secrets, she fired them and made sure they wouldn’t work in the area again. It’s impossible to confirm that FDR really was a client, but, quote, “it was well known that Roosevelt loved an old-fashioned stag party, and for his birthday every year he threw a men-only bash with all the trimmings.”95 We also know for sure that he had at least one extramarital affair, with Eleanor Roosevelt’s social secretary, so maybe he had more. Again, it’s impossible to prove but it’s not outside the realm of possibility.

On a much darker note, it was also rumored that she was involved, perhaps a little distantly, in the assassination of her one-time financier, Arnold Rothstein. He was shot on November 4 1928 at the Park Central Hotel on Seventh Avenue. His role as Big Bankroll of the New York criminal element hadn’t wavered much, but he had also started to not pay his own gambling debts. When Mayor Jimmy Walker was told that A.R. had been shot, he supposedly said, “That means trouble from here on in.”96 Another famed man about time, Ernest Cuneo said, “Rothstein alive had been an unsavory article, Rothstein dead was a calamity. The trail of blood left by the dying Rothstein led straight to the paths of corruption within the city machine.”97

It took A.R. days to die, and he was conscious for a lot of it, but he never named his murderer. So theories were flying up and down Manhattan. Some thought he’d been killed because of his gambling debts–he might have owed as much as $340,000, which is 6 million dollars today. Of course, this was dismissed often because, well, dead men don’t pay their debts. Others thought it was competition over drug dealing territories; he had gotten involved in the drug trade at some point. And of course, A.R. blackmailed people too, so it could have just been someone who decided their life would be easier if he was dead.

But pretty quickly, people started to settle on Polly’s buddy Smiling George McManus. The man who had been fun and charming in the early 20s had turned into a struggling alcoholic and a mean drunk by that point. Evidence pointing to his guilt included the fact that he’d summoned A.R. to his room at the Park Central Hotel less than thirty minutes before Rothstein was shot. A revolver, minus one bullet, was found on the sidewalk just outside and below McManus’s room. And, of course, McManus himself had disappeared. And, more damning, the police didn’t seem real intent on solving this murder! And remember, McManus was the youngest son of a cop, and several of his brothers on the force. Debby Applegate describes the NYPD’s sham investigation as having a quote “comical Keystone Kops quality.”98 Woof. And, of course, McManus was still running his famous high-stakes craps game; everyone was saying that it was McManus that A.R. owed the $300,000 to. So really no one actually wanted to see him behind bars, but also it was hard to argue with the fact that he was the most likely suspect.

I’m telling this story because Polly was nervous. Nervous enough that other people noted it. She never really said much on the subject, but the pieces are in press clippings. A hotel chambermaid at Park Central had noted that McManus had been drinking in his room with a pretty blonde in the hours before the murder; it was later found out that this was Ruth Keyes, a twenty-three-year-old “freelance model” who worked for Polly. In her testimony, Ruth said that “there were only two phone calls [to the hotel room that afternoon] and both were for me;” strange, since she wasn’t staying there.99 Why was she receiving calls to McManus’s room; a lot of people concluded that it was Polly calling, because only Polly knew she was there.

Polly has stated that she was nervous about potentially having to testify in the trial. Which, sure, would be bad for her because she had never yet had a charge of prostitution of being a madam stick. If she admitted in court that she had sent Ruth to George, well it would be her turn to be on trial again soon. But this doesn’t totally hold water; Ruth Keyes was interrogated again, and after that the district attorney announced he’d be filing for the arrest of a “Jane Doe.”100 He never said who this Jane Doe was, but he wanted to charge her with first-degree murder along with her alleged accomplices “John Doe” and “Richard Doe” who could only be McManus and one of his associates.

To be clear, Ruth is not the Jane Doe. She was released the same day. But Polly might have been. And with that, a different picture forms. What if she was involved in A.R.’s clumsy assassination? (I say clumsy because he survived for days.) It would explain how nervous she was. But there’s no clear motive for her. It’s just kind of a strange question mark in her life.

Despite the scare around A.R.’s death, business was still booming for Polly. If anything, the scandal probably tinted her house with a little edge, which was probably a little sexy. When the stock market crashed in 1929, Polly feared her business would dry up. But, as I mentioned with the moral crusaders, people will always find a way to access their vices, and this was no exception. Men still showed up to her house looking to forget their troubles, even just for a few hours.

Things got bad in 1930 though, when New York State Supreme Court Judge Samuel Seabury launched the largest investigation of municipal corruption in American history to date. Adler had made enough friend on the police force to earn an anonymous tip off that she was under investigation in connection with Seabury’s crusade. An anonymous caller told her, “Hurry, Polly, get out of your house. They’re on their way to serve you with a subpoena.”101 The Seabury Commission wanted to know why she had never once been prosecuted and jailed, despite an untold number of arrests by this point (even Polly had lost count). During questioning, former Assistant District Attorney John C. Weston admitted that he was, quote, “‘afraid of her influence’ and had ‘laid down.’”102 Thinking she was finally going to be thrown in jail, she fled to Miami and hid for six months. When she returned, two officers showed up at her door the very next day.

Interestingly, the Seabury Commission actually helped Polly. Despite her fears, she wasn’t sent to jail, and the Commission had been so effective it had actually kind of cleaned up the NYPD. In her memoir she reflected that the immediate impact was that, quote, “The police no longer were a headache; there was no more kowtowing to double-crossing Vice Squad men, no more hundred-dollar handshakes, no more phony raids to up the month’s quota. In fact, thanks to Judge Seabury and his not-very-merry men, I was able to operate for three years without breaking a lease.”103

She was not so lucky in 1936. The new mayor of New York, the reform-minded Fiorello LaGuardia was determined to clean up the city. According to Smithsonian Magazine, quote, “Within one minute of his swearing-in LaGuardia ordered the arrest of Lucky Luciano and followed up with a threat to the entire police department to ‘Drive out the racketeers or get out yourselves.’”104 Polly was arrested in July 1936 and ended up pleading guilty to “maintaining a disreputable apartment.”105 She served 24 days of a 30-day sentence at the House of Detention for Women. While there, she was held in a cell near other prostitutes. She wisely noted that, quote, “The only ‘reform’ offered these women is a term in jail with bad food and harsh treatment. The moment they have served their sentences they are shoved back into the world, with their bitterness against society more deeply rooted than before. Where could they go? What could they do?”106

When Polly was released, she was tempted to try to create a rehabilitation project to help, quote, “not only the old outcast prostitute or drunkard but for the young girls who feel the lure of the bright lights–a farm staffed by sympathetic, socially conscious volunteers, not the short of stuffed shirts who tell you, on a full belly, that YOU are not hungry. Why couldn’t I go out and campaign for such a farm, I thought to myself–and then I smiled, a little sourly. Polly Adler in the role of a social reformer was a lousy piece of casting, even in a daydream.”107 In fact, she had once tried to offer to pay for clothing, a tutor, and a vacation for the boys living in a Jewish orphanage, but the administrators apparently, quote, “concluded it was holier to snub one sinful woman than to give twelve little boys a summer of sun and happiness.”108 They never acknowledged her letter. So even though she was probably better positioned than anyone to determine what help women needed to avoid prostitution, she knew no one would take her seriously.

In fact, she tried to go legit in general after her short prison term. But it wasn’t meant to be: “A friend with a factory in New Jersey worried that associating with Madam Polly would hurt his credit. A nightclub owner said she’d be the perfect business partner if only the police would leave her alone. A restaurateur was similarly apologetic when she asked to work the hat-check and cigarette concession.”109 She realized, quote, “once you’re tagged as a madam it’s for keeps. I could never be a legitimate operator, my reputation would always be an insurmountable stumbling block. [...] I was a madam–or would be as soon as I’d plunked down a month’s rent and opened my little black book. I couldn’t live my reputation down–all right then, I’d live up to it.”110

Soon enough, she had regained the reputation of “the proprietress of ‘New York’s most opulent bordello’.”111 Though going legitimate hadn’t worked out, society still came to her. But things didn’t feel the same to her anymore. It wasn’t exciting anymore; she didn’t feel like she was on top or cheating the game of life. “It is one thing to embark on an enterprise under your own power, but when you are pushed into it–when it seems, as it did to me, that you have no other choice–then you start out bogged down by the ships on your shoulders, in the mood to make the worst of things instead of the best.”112 She “retreated into a shell of indifference” and the next couple of years were her unhappiest as a madam.113

Sick of New York, Polly tried her hand at shifting to Chicago. She had several clients in New York who actually lived in the Windy City, but when she called them up to say she was working in their hometowns, they made themselves scarce; it was a flop and she returned to New York very quickly. But it was in Chicago that another madam cheered Polly up and got her head back in the game. In a rare breakdown, Polly told her, “I wasn’t born in a whorehouse, and I’m not going to die in one!”114

Vicki, the madam, told her, “Seems to me, it’s a waste o’ breath bellyachin’ about the cards being stacked. And the way I look at it, somebody’s got to be a madam. Maybe madams ain’t considered respectable, but by God, Polly, the world ain’t ever been able to get along without ‘em… Leastwise not since civilization set in. I guess back when we was all living in caves and a guy got to feeling randy, he just picked up a rock and went huntin’--”115 The anthropological lecture got Polly laughing and finally snapped her out of her two-year depression.

In the late thirties, boxers and musicians became her main clients, including Frank Sinatra. The two struck up a genuine friendship and he inscribed her guestbook with “Polly–I adore you–Francis.”116

But also in the late thirties, the IRS suddenly decided that Polly had vastly underpaid her taxes from 1927 to 1930, and put a lien on her for $12,425 (over $250,000 today).117 She didn’t have the cash, so she went into hiding, but federal agents got word to her that if she didn’t come in, they would start raiding her businesses. This seems oddly polite to me.

Also in the late 1930s, Hitler’s rise in Germany saw an increase in Jewish immigrants to the US, including Polly’s family. She had managed to keep her life as a madam secret from them all this time, but that seemed poised to unravel now that everyone was finally living in New York. Moreover, Polly noticed that new challenges were arising for madams all over the city. She wrote, “Toward the end of the Thirties, an increasing number of my clientele seemed sexually maladjusted. As the tension in Europe grew, and war became ever more imminent, people’s peculiarities intensified. They seemed to get more and more off the beam. Whorehouses always draw twisted people who are unable to satisfy their desires normally, but now it got so that I began to think of a patron who wanted the simple, old-fashioned methods as a ‘truck driver.’”118 She did her best to fulfill every request, and if it was a particularly rare desire that most prostitutes wouldn’t agree to, whoever would she paid twice the usual rate. She was also known for providing safe hideaways for men interested in other men, though she didn’t keep any men as employees herself.119

This brings up an important point–past her teens, we don’t have stories of Polly dating. There is some speculation that she was a lesbian; according to Applegate,

She certainly had many friends in the lesbian and gay community and madde no effort to conceal it. She was regularly spotted in the ‘pansy clubs’ and was reported attending the famous Hamilton Lodge ball, an annual drag ball that had become a major event with thousands of spectators. [...] She reportedly showed up dressed in a male tux, à la Marlene Dietrich, along with about six of her girls who were similarly dressed. Polly and her girls participated in the climactic ‘Dance of the Fairies,’ before an audience of thousands.120

When the World’s Fair came to New York in 1939, Polly was written about in Fortune Magazine, an honor usually reserved for quote-unquote “legitimate executives.” She was mentioned in a visitor’s guide of everything to do in New York City, from the highbrow to the low, with Polly straddling both categories. It described her current apartment perfectly and even named her address in it, which amused her but also meant she had to pack up and move again. Reportedly, Mayor La Guardia was furious about this because it was “humiliating” that Fortune knew where Polly Adler was but he and his police did not.121

Soon after, “a spate of Pollyanna-Polly Adler mix-up jokes” landed her a mention in the New Yorker’s Talk of the Town section. Playwright George S. Kaufman dropped her name in his hit play The Man Who Came to Dinner, and she appeared under the pseudonym Molly Levine in Rion Bercovici’s book For Immediate Release.122 When Orson Welles decided he wanted to include a brothel scene in Citizen Kane, it was to Polly Adler’s house that he went to get a feel for how it should look; the scene was cut by Hollywood censors, but his signature in her autograph book survives.123 She became a fixture in teh best clubs in New York City, and befriended a young Desi Arnaz in the years before he met and became famous with Lucille Ball. She and her girls were always welcome at Copacabana, Frank Costello’s new supper club. It was possibly there that she met Joe DiMaggio, the New York Yankees’ star slugger when he first got to New York. All of them came to her house and she catered to their requests; DiMaggio apparently complained that his knees were slipping on her satin sheets so she kept a set of cotton ones on hand for him.124

Then Pearl Harbor was bombed and the US entered World War II. Lots of regulations like city-wide blackouts and food rationing should have hobbled her business. But, again, quote, “The more desperate the times, the more men seek the great escape of sex.”125 As in WWI, the streets of New York were filled with V-Girls, but this time, according to Polly, it was ambiguous if V stood for victory or venereal; mean, but true.126 She noted a “desperate, ‘devil may care attitude’ that she’d never seen before” in clients.127

Now in her early forties, Polly began to see the industry differently. A lot of her johns were young enough to be her sons; in fact some called her ‘Mom’.”128 In 1942, with apparently nothing better to do, the FBI started investigating her again. They saw their investigation as “the most important white slave case in the NYC Field Division.”129 J. Edgar Hoover pushed the agents personally; he and LaGuardia both were annoyed that she had escaped punishment for so long; not considering her three weeks of imprisonment in 1936.

In January 1943, Polly came down with pleurisy. She had to close the house down, because she was too sick to run it. She was being taken care of by a friend who was a nurse, but the police found her, trying to arrest her. She ended up being taken to a Bellevue hospital ward instead, though technically was still under arrest. By the time she was healthy enough to be discharged, she was also eligible for bail, so she managed to go home. Somehow, the case was dismissed in the meantime.

Briefly, she reopened her business, but she knew in her heart that she was done. “I felt like the Ghost in Hamlet,” she explained; the long illness had left her drained and “everything was an effort.”130 Later that year, she retired for good. She moved to Burbank, California where she finally achieved her goal of getting her high school diploma. She began coursework for a college degree but didn’t finish it. Polly took to calling herself madam emeritus during this time.131

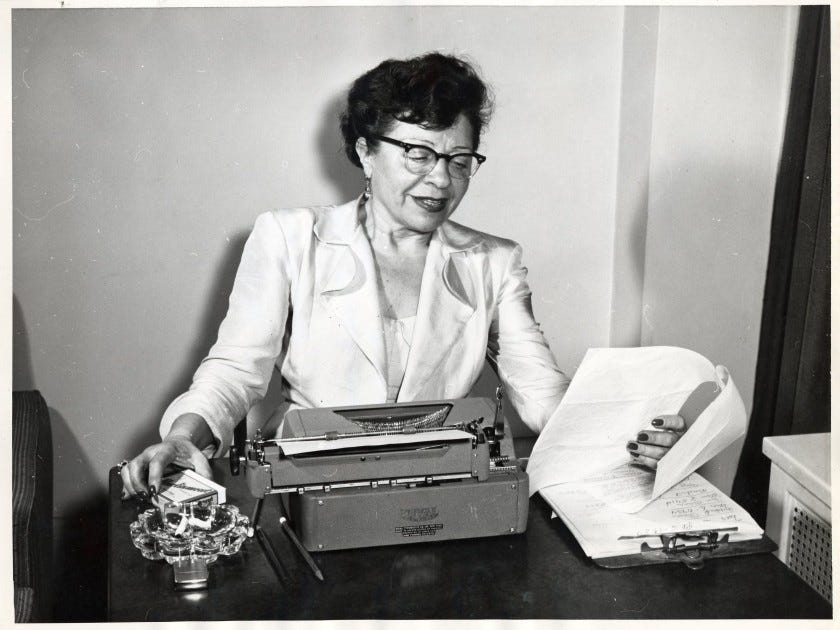

She also wrote her memoir, A House is Not a Home, with the help of ghostwriter Virginia Faulkner. The manuscript was, quote, “rejected by nearly all New York’s male publishers, who were fearful it would tarnish their reputations, literary agent Ann Watkins and publisher Mary Roberts Rinehart saw it for the gold mine it was.”132 When it was released in 1953, it was an instant bestseller and sold two million copies.133

The book spawned a film adaptation in 1964, with Shelley Winters playing Polly. Unfortunately, Polly didn’t live to see it. She died of lung cancer on June 9, 1962. She’s buried in Mt. Sinai Memorial Park in Los Angeles.

I’m so happy to have finally done this. I’ve been wanting to cover Polly Adler for over a year now. She is so fascinating to me because she was so aware of her role in New York society, and I tried to note in this episode the moments where she was way ahead of her time in terms of rehabilitation and sexuality and actual equality. As her biographer Debby Applegate noted in a New York Times review, quote, “It was not Polly but ‘her male criminal colleagues who became 20th-century cultural icons.’ ‘Sex workers in general … are dealers in illusion,’ she writes, and Americans do not like to see the curtain pulled back to reveal the mechanisms, let alone the banality, of their dreams.”134 Polly, as the facilitator of that, inhabits a weird space for people; she made their most secret desires possible but they also had to pay for it, which can make anything feel a little tawdry, like it wasn’t worth it.

And that is the story of Polly Adler! I’m sorry episodes have been a little irregular lately, but I think I’m getting back on track. If you liked this episode, please tell a friend about it. You can also let me know your thoughts by sending me a note. I’m on Twitter and Instagram as unrulyfigures. You can also follow Unruly Figures on Substack, where I post tons of bonus content. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks find this work. Thanks for listening!

📚 Bibliography

Abbott, Karen. “The House That Polly Adler Built.” Smithsonian Magazine, April 12, 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-house-that-polly-adler-built-65080310/.

Adler, Polly. A House Is Not a Home. Farrar & Rinehart, 1953.

Applegate, Debby. Madam: The Biography of Polly Adler, Icon of the Jazz Age. Doubleday, 2021.

———. “The Literary Adventures of Polly Adler, the Algonquin Round Table’s Favorite Madam.” Literary Hub (blog), November 2, 2021. https://lithub.com/the-literary-adventures-of-polly-adler-the-algonquin-round-tables-favorite-madam/.

Bren, Paulina. “The Manhattan ‘Madam’ Who Hobnobbed With the City’s Elite.” The New York Times, November 2, 2021, sec. What To Read. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/02/books/review/madam-polly-adler-debby-applegate.html.

Darcella, Aria. “Polly Adler, the Glamorous Madame of Jazz Age New York.” Avenue Magazine, June 13, 2022. https://avenuemagazine.com/notorious-polly-adler-new-york-history/.

Ghert-Zand, Renee. “How Jewish Immigrant Polly Adler Ended up Running Prohibition’s Hottest Bordello.” Accessed May 11, 2023. https://www.timesofisrael.com/how-jewish-immigrant-polly-adler-ended-up-running-prohibitions-hottest-bordello/.

Mayo, Michael. “On Theda Bara and the Origins of the Vamp.” CrimeReads (blog), September 27, 2022. https://crimereads.com/theda-barra-origins-vamp/.

FYI: A few of the links in this post are affiliate links. That just means if you click through a buy a book, I’ll get a few cents of profit but it won’t cost any more for you.

Applegate, Debby. Madam: The Biography of Polly Adler, Icon of the Jazz Age. Doubleday, 2021.

Applegate, 21

Applegate, 23

Applegate, 23

Applegate, 23

Applegate, 26

Applegate, 29

Applegate, 30

Applegate, 31

Applegate, 37

Applegate, 37

Adler, Polly. A House Is Not a Home. Farrar & Rinehart, 1953.

Applegate, 40

Applegate, 40

Applegate, 40

Applegate, 41

Adler, 12

Applegate, 50

Applegate, 53

Applegate, 51-2

Applegate, 52

Applegate, 55

Applegate, 55

Applegate, 57

Applegate, 57

Applegate, 58

Applegate, 58

Applegate, 58

Applegate, 59

Applegate, 60

Applegate, 60

Adler, 19

Applegate, 62

Applegate, 62

Applegate, 62

Applegate, 66

Applegate, 66

Applegate, 66

Applegate, 69

Applegate, 69

Applegate, 69

Applegate, 65

Adler, 19

Adler, 19

Adler, 19

Mayo, Michael. “On Theda Bara and the Origins of the Vamp.” CrimeReads (blog), September 27, 2022. https://crimereads.com/theda-barra-origins-vamp/.

Applegate, 65

Adler, 23

Adler, 29

Applegate, 82

Applegate, 83

Adler, 31

Applegate, 89

Applegate, 92

Applegate, 100

Applegate, 100

Applegate, 100

Applegate, 109

Adler, 40

Adler, 42

Applegate, 112

Applegate, 112

Adler, 42

Abbott, Karen. “The House That Polly Adler Built.” Smithsonian Magazine, April 12, 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-house-that-polly-adler-built-65080310/.

Adler, 44

Adler, 49

Applegate, 132

Applegate, 132

Adler, 55

Applegate, 115

Applegate, 119

Applegate, 118

Applegate, 129

Applegate, 130

Applegate, 130

Applegate, 131

Applegate, 131

Applegate, 157

Applegate, 158

Applegate, 158

Adler, 56

Applegate, 158

Applegate, 158

Applegate, 158

Adler, 57

Adler, 57

Adler, 57

Adler, 59

Adler, 61

Abbot

Applegate, 166

Adler, 65

Adler, 65

Adler, 65

Applegate, 281

Applegate, 286

Applegate, 289

Applegate, 290

Applegate, 291

Applegate, 294

Adler, 168

Abbot

Adler, 199

Abbot

Abbot

Adler, 266

Adler, 267

Adler, 267

Abbot

Adler, 283

Adler, 285

Adler, 286

Adler, 286

Adler, 316

Adler, 317

Applegate, 411

Applegate, 413

Adler, 338

Applegate, 417

Applegate, 417

Applegate, 419

Applegate, 419

Applegate, 419

Applegate, 421

Adler, 341

Adler, 341

Applegate, 424

Applegate, 242

Applegate, 424

Adler, 348

Abbot

Darcella, Aria. “Polly Adler, the Glamorous Madame of Jazz Age New York.” Avenue Magazine, June 13, 2022. https://avenuemagazine.com/notorious-polly-adler-new-york-history/.

Darcella

Bren, Paulina. “The Manhattan ‘Madam’ Who Hobnobbed With the City’s Elite.” The New York Times, November 2, 2021, sec. What To Read. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/02/books/review/madam-polly-adler-debby-applegate.html.

Share this post