Exciting news in book release land—I’ll be at a few book-related events in the coming weeks.

I will be at…

Interabang Books - Dallas, TX - March 8 @ 6 pm CT - RSVP here

Booksoup - Los Angeles, CA - April 5th @ 7 pm PT - RSVP here

I’ll also be doing a virtual event in late March—more details on that one are coming!

🎙️ Transcript

Hey everyone,

Hope everyone is doing well today! I am excited to share with you an excerpt from a chapter of my upcoming debut book. The book had chapters that cover several people that I have never covered before on the podcast, so I wanted to share a little taste of what one of those chapters is like.

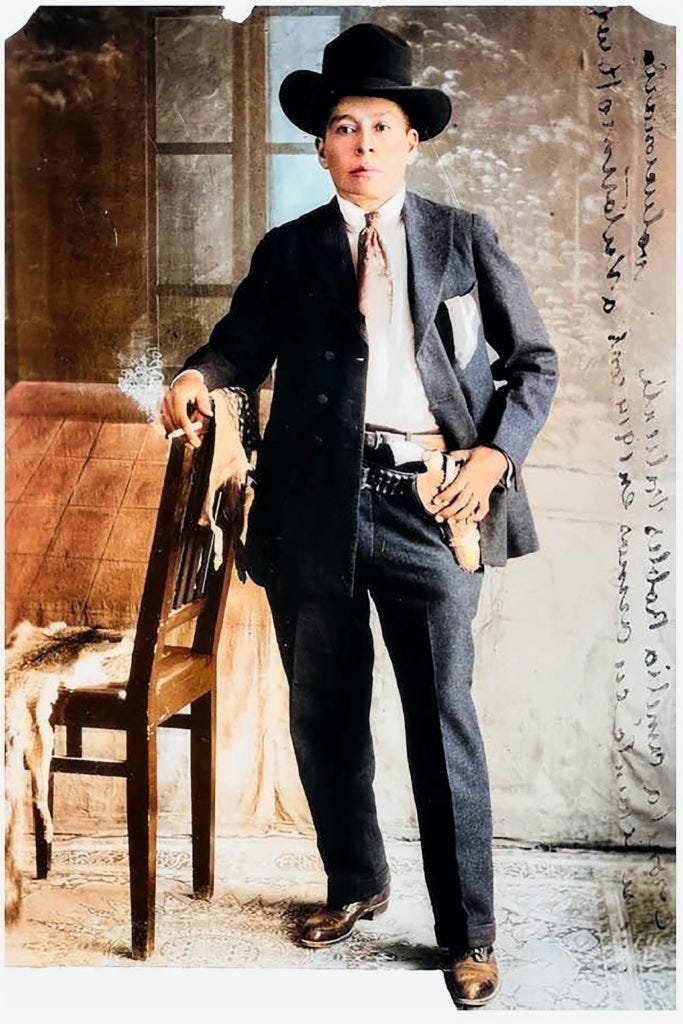

The story of Amelio Robles Ávila is a fascinating one because he complicates and confounds so many of the stereotypes of Mexican gender roles during the Mexican Revolution. Though he didn’t have the same language we use today, he lived openly as a transgender man, using masculine pronouns and masculine-gendered adjectives in Spanish while fighting in the war. He was a brave fighter and ultimately something of a bad boy, enforcing his masculinity through negative stereotypes of machismo culture like violence and womanizing.

If you like this excerpt, you’re going to love the book it’s a part of. Preorder Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries today.

The Mexican Revolution (1910–20) made room for more than just a new national government in Mexico; for many, it created room to take on new identities and forge new futures for themselves. Amelio Robles Ávila was one of those people.

One of the earliest recorded transgender figures in Latin America, Robles was assigned female when he was born on November 3, 1889. Growing up in Xochipala, rural Guerrero, at the turn of the twentieth century, Amelio came from a family of ranchers. They were midsize landowners, and when the Mexican Revolution swept through, they, like similar families, took center stage.

Amelio’s father, Casimiro Robles, died when Amelio was young. His mother, Josefa Ávila, remarried, but Amelio apparently never got along with his stepfather.1 He had several siblings and half-siblings, many of whom he remained close to his entire life. As landowners, most of the family never moved out of Xochipala.

Probably as a preteen, Robles joined the Daughters of María, a Catholic group “dedicated to refining young women’s spiritual education.”2 This meant that the nuns taught the girls traditional female tasks, like cooking and cleaning, in addition to overseeing their religious studies. By some accounts, Robles had a rebellious nature even as a teen, which couldn’t be tamed even by the nuns he saw daily.3 Around this time, Robles “courted a schoolmate as her beau.” Though Robles still dressed in traditionally feminine clothing at this point, he generally took on the “masculine” role in romantic relationships, mimicking heteronormative expectations for relationship roles. That included pursuing and seducing the schoolmate he was interested in.

As was expected, Robles worked in the family restaurant, which served food to revolutionaries passing through the area during the early stages of the revolution. He also learned how to handle weapons and became adept at riding horses. His prowess with a firearm atop a horse was seen as a “good spectacle” in his hometown. As a youth, Robles wanted to grow up to be a doctor, a traditionally masculine profession.

In 1910, dictator Porfirio Díaz won another term as president in a sham election. Díaz had handpicked aristocratic Francisco Madero to run against him, knowing he would lose. However, Díaz had not expected Madero to become popular enough to successfully lead a military revolution against him.

After the election, Madero had temporarily fled to Texas, proclaimed himself president of Mexico, and reentered Mexico, collecting groups of peasant guerrilla forces with him as he traveled south. One of these groups was the Liberation Army of the South, led by Emiliano Zapata. Zapata had a history of forcefully winning power and land for the oft-ignored mestizo and Indigenous people in the state of Morelos, in south-central Mexico, and had emerged as a leader and voice for the people.

Zapata’s forces defeated Díaz’s army in the Battle of Cuautla in May 1911. Díaz later admitted that the fall of Cuautla convinced him to resign. The Mexican government, deeply in debt and unpopular, collapsed, and Díaz retreated into exile in May 1911.

October 1911 saw Madero formally elected to office. But by November, it was clear that the inexperienced leader didn’t know what he was doing. Frustrated by what he saw as Madero’s betrayed promises, Zapata wrote and published the Plan of Ayala in late November, which called for land reform and denounced Madero’s presidency.4 It effectively united smaller rebellions and general discontent under the goal of redistributing land that had been bought up and stolen by wealthy landowners and consolidated into large haciendas.

Under this call, Robles joined Zapata’s Liberation Army in 1912 or 1913. According to historian Gabriela Cano, Robles’s inspiration might have been less about the agrarian cause than about “passion for the intensity of war, so full of dangers and strong emotions.” Later in life, when reminiscing about the revolution, Robles said little about agrarianism and politics and more about the daily life of the battlefield and exploits with comrades.

Though Robles had always preferred masculine hobbies, it’s unclear when he began wearing masculine fashion and asking that people use masculine pronouns to refer to him. Possibly it began in 1911 or so, when many women began adopting masculine clothing for safety. War zones are often sites of sexual violence against the female population, and effectively disguising oneself as a man could go a long way to avoiding this inhumanity.

However, the women in Mexico who adopted male disguise for their safety or to fight in the revolution usually removed their disguise once the war was over. (Women who fought in Zapata’s army include Colonel Juana Gutiérrez de Mendoza, who lobbied Zapata to stop the abuse soldiers perpetrated on women.) Beginning his transition might have been easier in such a historic moment, but it’s clear from his personal accounts that safety was not his primary motivation. By adopting traditional masculine dress and going to war, Robles was living out his true self, not hiding. As a guerrilla fighter, Robles discovered “the sensation of being completely free.” Regardless of when he began externally showing his transition, Robles was well-established as a man by his mid-twenties.

Robles clearly embodied the ideal revolutionary soldier. He was courageous and often daring, “responding to aggression immediately and violently.” His comrades “admired his precise emulation of a masculinity understood as a display of strength and violence.” In many ways, Robles both confirmed Mexican gendered stereotypes of behavior while simultaneously confounding them by the very nature of his existence.

Preorder your copy of Unruly Figures wherever books are sold!

Laura Martinez Alarcón, “La Coronela es un hombre y, sin embargo, nació mujer,” Actitudfem, March 7, 2016, https://www.actitudfem.com/entorno/genero/lgbt/la-coronela-es-un-hombre-y-sin-embargo-nacio-mujer.e

Gabriela Cano, “Unconcealable Realities of Desire,” in Sex in Revolution: Gender, Politics, and Power in Modern Mexico, ed. Jocelyn Olcott, Mary Kay Vaughan, and Gabriela Cano (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), 43.

Unless otherwise noted, all quotes and facts in this chapter come from this publication.

Martinez Alarcón, “La Coronela es un hombre.”

Emiliano Zapata and Otilio Montaño, “Plan of Ayala,” November 25, 1911, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667593/.

Share this post