Hello everyone,

Hope you’re all doing well wherever you are. I’m really excited to share the story of the pirate Barbarossa, as he’s known in Anglophone countries.

While you’re here, don’t forget to preorder my book, Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries, out on March 5!

🎙️ Transcript

When we tell stories of pirates in pop culture, they’re usually about characters like Captain Jack Sparrow swaggering through the lush Caribbean with a bottle of rum in his hand and freedom in his heart. The Golden Age of Piracy of the 17th century is what we’re picturing, but pirates have sailed and stolen on the high seas since—well, since we figured out how to make boats. So today I’m telling a story of an earlier pirate whose name you might not know: Barbarossa.

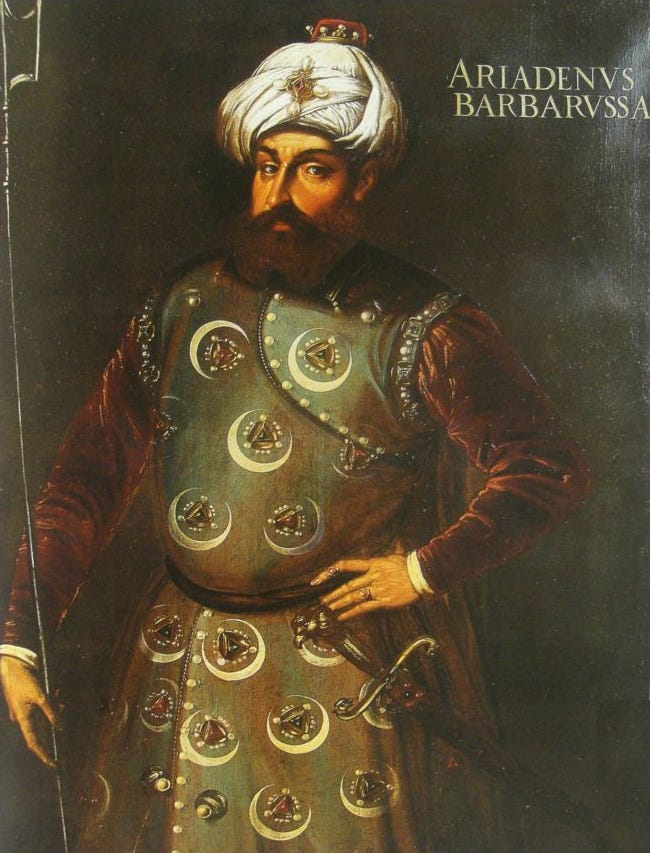

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Castellanos Clark, and today I’m covering the tale of Hayreddin Barbarossa, a legendary pirate from the 16th century. He harassed Spanish shipping in the Mediterranean and helped his older brother establish a kingdom in modern-day Algeria.

Before we jump into the tale of piracy on the high seas, I first have to thank all of the paying subscribers on Substack whose patronage helps me make this podcast possible. This podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! If you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber over on Substack! When you upgrade, you’ll get access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates on the upcoming Unruly Figures book. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com

All right, let’s hop into it.

He is known by many names. He was born Khizr on the island of Lesbos around 1478. In a lot of the Mediterranean, he’s remembered by an honorific he was given later in life, Kheir-ed-Din, which means ‘defender of the faith’ and sometimes gets translated as Hayreddin. In the West, he’s best known by his moniker Barbarossa or Redbeard, but I’ll be calling him by his first name, Khizr, throughout this episode. We’ll come back to why.

Because of the time we’re going back to, there are pieces of his life story that are a bit conflicted, starting with his heritage. Though it’s well-documented that his mother was a Greek widow named Katerina, where his father came from is something of a mystery. Biographer Ernle Bradford, in his book The Sultan’s Admiral, supposes that his father, Ya’kub, was a retired janissary. The janissaries were an elite military force created by kidnapping young Christian boys from neighboring kingdoms, forcibly converting them to Islam, and then giving them a lifetime of military training. So Ya’kub could have been from anywhere in Eastern Europe really—Greece, Romania, Albania, Serbia… et cetera.

Ya’kub and Katerina moved to Lesbos, an island in the Aegean Sea in 1462, when the island was taken from the Genoese and incorporated into the Ottoman Empire. As was tradition, high-ranking and deserving soldiers were given property on newly conquered lands. It’s possible that Ya’kub retired and married Katerina around the same time—janissaries were not meant to marry or have any other trade until they retired, usually around 40. The couple had six children: two daughters and four sons; unfortunately, only the names of the boys are recorded in history. They were Oruç, Ilyas, Ishak, and Khizr.

From the island, Ya’kub began to trade as a potter. He made his items and delivered them to neighboring islands by boat. Once they were old enough, his children began to help him. Oruç helped out on the boat, Ishak became a carpenter, and Khizr helped out in the pottery. Only Ilyas studied to become an imam and had little to do with the business. An almost-contemporary named Diego Haedo, a Spanish historian priest, referred to this early childhood in admiring terms; Bradford notes that many contemporaries and early historians saw Ya’kub and his wife as, quote, “a model family: no hint here at all of bad upbringing leading to violent or ‘disgraceful’ lives.”1

Throughout his biography, Bradford often compares Khizr’s early life to the life of Sir Francis Drake, an explorer, sailor, and sometimes pirate whom many people in Europe and the US know a little better. Both were raised in, quote, “poor, but religious, environment, taught a craft, and expected to fend for themselves as soon as they reached manhood.”2

Oruç had helped out on the boat, and fittingly was the first one to go to sea, along with his brother Ishak. They captained a small galleot. Sometime in or around 1490, they had a disastrous run-in with the Knights of St. John, also called the Knights Hospitaller. Oruç and Ishak were probably doing legitimate trade with a little piracy on the side—the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire often encouraged independent citizens to harass the remaining Genoese who occupied islands so close to Turkey. The run-in was accidental; both ships seem to have come around an island and spotted each other at the same time. Though the ship Oruç and Ishak captained was probably faster, luck was not on their side that day and they were attacked by the larger galley.

The first shots fired by the Knights killed Ishak immediately. Oruç was caught and pressed into slavery aboard the galley, manning the oars below deck. This was a brutal and exhausting job—and both sides practiced it. The Christian ships, including ships from the Papal states, often had Muslim slaves below deck rowing, and Muslim ships often had Christian slaves below deck.

It’s unknown how long Oruç was enslaved. Most accounts say that the ransom for his return was paid and he was freed. Other accounts claim that Oruç wasn’t pressed into service at all but held as a prisoner at Bodrum Castle, which the Knights of St. John owned. In this version, Khizr spends months—maybe years—searching for his eldest brother and eventually breaks him out of Bodrum Castle and they escape into the night.

This second story is certainly the more romantic and piratical version, but it doesn’t really hold up to scrutiny. There’s no record of the castle being used as a prison before 1895, and it doesn’t fit in with the tradition of maritime capture at this time.

In any case, Oruç is released and reunited with his family. Today we’d probably say that Oruç had PTSD after his ordeal; when Bradford wrote his biography, he phrased it as, quote, “his harsh training at the oar had not made him any great lover of Christians.”3

On March 31, 1492, the Mediterranean world was shaken by Spain. King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I announced that Jews and Muslims who would not convert to Catholicism had to leave Spain by the end of July. Thousands of people fled across the Mediterranean to the shores of North Africa or to other parts of Europe where they felt safer. Jewish people who did convert were called conversos and Muslims who converted were called moriscos; both groups would be haunted by accusations that they practiced their faiths in secret for generations.

Before this edict, relations between North Africa and southern Europe had been relatively good. They were well-connected in terms of trade, at least. But this expulsion inspired revenge in the hearts of people who had lost their homes. As Bradford writes, quote, “No sooner were the banished moors fairly settled in their new seats than they did what anybody in their place would have done: they carried the war into their oppressors’ country.”4

About eight years later, Oruç and Khizr arrived in North Africa on two ships. We’re not sure what they were up to at first, but it seems clear that Oruç was in charge and Khizr was a member of the crew. Already they were doing something a little differently than other maritime powers—they used a crew of Turkish freemen, rather than enslaved Christians, to power their boats. The galleots they used required two to three people to an oar, and on large boats like where Oruç had been captured, the enslaved oarsmen were usually chained in place.

Perhaps because of his experience, Oruç preferred to use free men because he found them more efficient and more trustworthy—enslaved people could, quote, “be expected to mutiny at the first available opportunity.”5 They also couldn’t be fighters because they were chained in place belowdeck. At the start of a battle, there might not be time to unlock them and—again—they might turn against their captors. And, let’s be honest, having oarsmen who doubled as fighters both made the ships lighter and also denied folks the time to plot and scheme.

However, we shouldn’t assume they didn’t participate in slavery at all. Captured Christians did get sold into slavery by the brothers. There are also some reports that when the brothers sailed out, they had one large galley with enslaved rowers, where all their food and treasure were stored, and several smaller galleots, which were much faster and more maneuverable in a fight.6

In 1504 they arrived in Tunis with their ships. They set up a deal with the Sultan of Tunis where they would give him a percentage of all their captured booty if he would allow them free use of the harbor, La Goletta. They made good use of it, sallying out to capture ships and people along the coasts of Sicily and Calabria.7 They were immensely successful, bringing an untold number of Christians to Tunis to be either enslaved or ransomed.

European powers noticed basically immediately. In a normal shipping season, which in Europe at the time was during the warm summer months, let’s say April to September, depending on the region, during that season, they might lose a few ships to bad luck and bad weather. But as the summer of 1504 came to a close, it became clear to the kingdoms along the Mediterranean coast that more was happening and it might require a concerted effort to put a stop to it. However, Europe at the time was not peaceful—kingdoms were competing and at war with one another. Bradford writes, quote, “the extraordinary success of the Barbarossas over the years to come was largely promoted by the fact that ‘a house divided against itself cannot stand.’”8

And I guess it’s here that we should talk about the nickname, Barbarossa. Bradford uses it in the plural, even though that’s not a surname for Khizr or Oruç. In fact, the nickname comes from Oruç’s red beard—barba rossa is just Italian for “red beard” and the moniker got applied as Oruç’s legendary status as a competent and violent pirate grew along the Italian peninsula. Khizr, who is the much more famous brother today and who I’m actually covering in this episode, didn’t have a red beard; by most accounts, his hair was dark brown or black. He took on the mantle of Barbarossa after his brother’s death—I know, spoilers—sort of like a character that one plays. But the name actually can refer to both brothers, though most people are referring to Khizr when they use it.

Over the next few years, they grew rich by taking ships in the Mediterranean. They occasionally attacked ports, but not as often as is portrayed in pirate movies—after all, if you destroy a port, ships stop going there. They became so well known that other aspirational pirates volunteered to join their efforts, and their fleet grew under these lieutenants.

In addition to robbing ships, there are also reports that Khizr specifically began to help ferry moriscos and Muslims who were being oppressed in Spain across the water to North Africa. He took them to places like Tangier, Algiers, and Tunis, helping them find places where they could practice their faith safely. It’s hard to say when this began—my guess is as early as they got near the Spanish coast.

Their power became centralized along the northwest coast of Africa, mostly around Tripoli in the southeast, up toward Tangier, right across the straight of Gibraltar where Spanish ships often got trapped coming home from the “New World” that Spain was just starting to colonize. They sometimes made it as far south along the Moroccan coast as Rabat, but not often. Their power was most dominant between Algiers and Tripoli, especially as they established their base on the island of Djerba around 1510. In fact, Djerba later became known as, quote, “the lair of the Corsairs.”9

It’s worth exploring why the brothers were attracted to this part of the world. It was far from the reach of the Ottoman Empire, which allowed them to act independently. It also gave them access to Italian and Papal shipping—these wealthy powers had the most to steal from. But it also probably had something to do with the quote-unquote “New World” that was quote-unquote “discovered” by Christopher Columbus while sailing under the Spanish flag. Word had got back to Europe in 1493 and spread quickly, and when Spanish ships began to regularly return to Spain loaded down with gold and gems, it was probably an irresistible draw.

And it quickly became clear to the brothers that Djerba was not close enough to those lucrative shipping routes. It was a great refuge—tricky sailing for anyone not familiar with the island—but it was far and didn’t have the timber that they needed to build and repair ships.

Oruç, still leading things at this point, turned his eyes to Bougie, a Spanish garrison 120 miles east of Algiers. Not only did it have a good harbor, but behind it, quote, “soared the high peaks of Mounts Babor and Tababor, both crowed with fir and cedar—ideal for shipbuilding—while the surrounding countryside, blessed with a high rainfall, was rich in every kind of vegetable, fruit, and cereal crop.”10

The thing is, Oruç was ambitious and he had decided that the sea was a means to an end. He wanted a land empire, he wanted to be a sultan himself. Enriched and powerful from capturing ships, he decided that 1512 was the year to make this happen. He prepared all spring and early summer—probably to the relief of Europeans who managed to go all summer unmolested by pirates—and attacked the city in August.

For seven days they laid siege to the city. The guard fort crumbled and the pirates clambered ashore, ready to kill or scare away the Spaniards—but something went wrong. Oruç was shot and it, quote, “took away his left arm, above the elbow.”11 Unable to continue, his fighters stopped and took him back to the ship to save his life; the city was saved. Many assume that if the pirates had just left Oruç where he lay, they could have taken Bougie that day, but as it was they retreated to Djerba.

While Oruç lay recovering in Tunis—which took over a year—Khizr came into his own as a leader. Nearly immediately he captured a ship that belonged to a wealthy Genoese family that was heavily leaden down with treasure. He towed it back to Tunis, where they still had a deal with the local sultan.

But this theft opened Pandora’s box. The Genoese were furious about the stolen ship and they came after Khizr and the Turkish corsairs. A squadron of ships, commanded by the famous Andrea Doria, attacked Tunis. Khizr sank six of their own ships in the harbor to prevent them from being stolen, and then sailed out to battle the Genoese in their much larger galleys. They were routed—they barely escaped with their lives, and the Genoese stole the six ships that hadn’t been sunk. They also burned down the fort guarding the harbor, enraging the Sultan of Tunis.

Khizr, perhaps sensing that everyone was pissed, raised the six ships he’d sunk—didn’t know you could that before this story—and sailed them Djerba, where he waited for his brother and his sultan to cool off. During the fall and winter, he and his sailors built three new galleots, replacing some of the ones lost to the Genoese, and established a powder mill to manufacture gunpowder.

Once Oruç had finished recovering, they attacked Bougie again. They started the siege in August 1514, and the city might have fallen if the Spanish crown had not coincidentally sent the annual autumn relief of ammunition and other supplies for the garrison to survive the winter. Instead, just as the city was starting to weaken, five large men-of-war ships arrived, and Oruç and Khizr were forced to retreat.

Instead of Djerba, they went to Jijel for the winter. The peninsula was close to Bougie, suggesting Oruç intended to go right back for a third siege when the weather calmed in the spring. Their 1,100 sailors, plus several more adventurers, settled in or the winter, careful to treat the native inhabitants of Jijel well so they would be welcomed back in the future.12

But something must have changed. We’re not sure what—but 1515 did not see them return to Bougie. In 1516, King Ferdinand of Spain died, and the people of Algiers, which had long been dominated by Spain, reached out to their neighboring Arab ruler, Sheikh Selim, to help them drive out the Spanish garrison in that moment of Spain’s weakness. Selim, in turn, reached out to Oruç and Khizr, quote, “inviting [them] to participate in the liberation of Algiers.”13

They agreed and set out—but then they passed Algiers for a small port called Cherchell. There, another Turkish corsair had set himself up as a local Sultan—a man called Kara Hassan. Oruç didn’t believe there was enough room for both of them on that stretch of coast, so he attacked and killed Kara Hassan. He took over Cherchell, left a few trusted men in charge, and then returned to Algiers, where he finally began the siege he’d promised.14

For 20 days, the pirates under Oruç and Khizr tried to destroy the walls of the fort. But their ordinance was too light, and the fort too strong. Now, a few details seem to be missing from this story because the next thing we know is that Oruç had decided that in order to drive the Spaniards out of Algiers, he needed to kill his ally, Selim. Which seems like a big leap—we started at point A and ended at like… K. What happened in between is unclear; perhaps Selim was not a good military commander and was holding back Oruç’s efforts to defeat the Spaniards? I’m not sure.

Either way, Oruç stands accused by history of murdering Selim, though we’re also not sure how that happened. Some accounts claim he was hanged in the city, but more believable accounts say that Oruç snuck into Selim’s bath and suffocated him with a wet towel.15 People were told Selim had died of a stroke, and Oruç was declared sultan of the city.

Now, the Spaniards were still in their fort at the edge of the city. Until that moment, they had had a deal with the citizens of Algiers—as long as they kept to themselves, the Spaniards would too. But that deal was clearly off, so the Spaniards began attacking the city, making life impossible for the inhabitants. The citizens of Algiers suddenly realized that they had escaped the pot only to the land in the fire; life got much worse. The fighting continued and in late 1516, the Spaniards were finally driven from the city of Algiers.

Oruç had what he wanted. He was the sultan of a region of what is today Algeria. In 1517, the Spanish tried to reclaim the lands Oruç had claimed, but he and Khizr managed to defeat the Spanish fleet. When they fled, Khizr took several galleots and gave chase, attacking Spanish cities along the coast. They burned and looted cities, kidnapped slaves, and brought oppressed Muslims to North Africa.16 Some of the prettiest women were sent onward to Turkey, destined for the harem of Selim I (a different Selim than the one killed by Oruç).

Satisfied with his wins, Oruç retreated to a town further from the coast: Tlemcen. From there, he began to send diplomatic envoys to Fez and Tunis, establishing relations and having himself recognized as a ruler by his neighbor. Khizr remained in charge of Algiers, where he heard rumors of a Spanish attack on Tlemcen.

Oruç reached out to the Sultan of Fez for help. The Sultan promised to send soldiers, but then he delayed, just long enough for the Spanish soldiers to arrive. Oruç led his soldiers from the city, but they couldn’t evade the Spanish, and Oruç was killed in a battle. The crimson cloak he was wearing when he died was later taken to Cordova to be displayed, and his head was removed to be taken as proof of his death to the Spanish rulers.17 Apparently so many had claimed to kill Oruç before and been wrong—or liars—that they wanted incontrovertible proof. Garcia de Tineo, the man who killed Oruç, was allowed to incorporate Oruç’s head into his coat of arms—very Medusa-like, right?

In fact, even though Oruç had been a thorn in the side of the Spanish for a long time, after death he was treated to heroic poems. It’s such an interesting turn, that it reminds me a little of that brief moment late last year on TikTok when people were claiming that Gen Z loved Osama Bin Laden. Obviously, that ended up being way blown out of proportion—Gen Z does not support terrorism at large—but it was that strange pattern of glorifying an enemy that you’ve already killed almost because he doesn’t represent a threat anymore.18 It’s an interesting psychological phenomenon.

Anyway, once Oruç was dead, Khizr turned around and reached out to Sultan Selim I in Turkey. Though his brother was dead, his kingdom had not fallen yet, and Khizr rightly guessed Selim would be interested in supporting an Ottoman outpost in far-west North Africa. Selim said yes, granted Khizr the title ‘Beylerbey,’ a very high rank in Ottoman society, equivalent to Governor-General, and sent him military reinforcements.

Strangely, the Spanish military actually retreated after this success at Tlemcen, which gave Khizr time to wait for reinforcements and build up his strength. He had 22 ships ready to go in Algiers, and he reinforced garrisons along the coast. Then he lay in wait, sure that Charles V, King of Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor, would send an attack any day.

It came in 1519. But Charles V was not content to just send the Spanish military—he had spent the intervening winter and spring contacting the Genoese, the Monégasques (citizens of Monaco), the Neapolitans, the Pope, the Knights of St. John, the mercenary Andrea Doria, and the French. All except France contributed ships to make an enormous fleet of fifty war galleys and up to 450 transport ships.19 Clearly, they intended to do more than take back Algiers—this was an attempt to drive the Turks out of North Africa entirely.

But, as with any group project, it took a lot longer than Charles V thought. It would have been ideal to launch the attack in June or July, when summer made the Mediterranean calmer, but they didn’t leave until late August. They arrived at Algiers on August 24 under a shadow of clouds. Nearly as soon as they landed, the storm broke: Waves began to, quote, “burst in rolling fury…anchors dragged, cables broke, ships collided… Soon the invasion fleet was scattered up and down the coast.”20 Hundreds of men drowned and at least twenty ships were completely destroyed. It remains one of the worst maritime disasters in Mediterranean history. All Khizr’s soldiers had to do was wait on the beach as the ships broke apart and sailors and loot washed up on shore. He sat back that winter, wealthier than he’d ever been, secure in his safety.

From 1520-1529, we don’t have a lot of details about what Khizr was doing. Historians think he married an Algerian woman around this time; they had one surviving child together, a boy named Hasan. We know he brought the coast of Algeria further under his control, consolidating power. With a lot of good lumber at his back, he was able to expand his fleet, and soon Khizr alone was a naval power to contend with. Even countries like England, which had previously been safe from corsair predation in the Mediterranean, found their merchant ships attacked both in the Mediterranean and along the western coast of Portugal. Khizr himself sailed often, leaving his capital, Algiers, under the trusted supervision of Hassan Aga.

As Khizr’s power grew, he attracted, quote, “Christian renegades” who enjoyed his protection to do their own piracy and looting.21 They came from France, Venice, Genoa, Sicily, Naples, Spain, Greece, Hungary, Albania, and further. Much like the Sultan of Tunis had done for him and Oruç early in their career, Khizr allowed people to sail in his waters with his approval as long as they paid him a percentage and came to his aid if European powers attacked again.

Soon, Algiers became incredibly wealthy. The abbot I mentioned earlier, Diego de Haedo, wrote, quote, “They have crammed most of the houses, the magazines, and all the shops of this Den of Thieves with gold, silver, pearls, amber, spices, drugs, silks, cloths, velvet, & c., whereby they have rendered this city [Algiers] the most opulent in the world: insomuch that the Turks call it, not without reason, their India, their Mexico, their Peru.”22 And much like how Spanish treasure ships financed voyages to North America through investments by merchants, Algerian tradesmen invested in the building of galleys that would then rob those treasure ships.

As contact between Algerian and European ships increased, many people noted that the pirates were better seamen than their European rivals. Haedo wrote, quote, “their galleots are so extremely light and nimble, and in such excellent order… the Christian galleys are so heavy, so embarrassed, and in such bad order and confusion, that it is utterly in vain to think of giving them chase, or of preventing them from going and coming, and doing just as they themselves please… When at any time the Christian galleys chase them, their custom is, by way of game and sneer, to point to their fresh-tallowed poops, as they glide along like fishes before them.”23 This is really interesting because Spanish ships were often considered some of the best in the world at this time, but a Spaniard himself is denying that claim.

Around this time, Khizr earned the title Kheir-ed-Din—”Protector of Religion.”24 The title probably came up because of the way that he had helped many Muslims escape Spain for safer shores—estimates cap out around 70,000 people that he helped escape servitude and prejudice in Spain.25 and he’s still remembered this way in a lot of the Mediterranean. Sources that don’t call him Barbarossa often call him Kheir-ed-Din. Fun fact though, Kheir-ed-Din could also be translated as Defender of the Faith, a title that Henry VIII was given in 1521, just about the same time that Khizr was. This isn’t really important, though I do think it’s funny that two defenders of two different faiths were floating around at the same time—though Henry didn’t keep that title for very long.

As Khizr aged, he focused on training the lieutenants and captains who managed ships in his fleet. In 1529, that training paid off when three captains in their small galleots came up against eight large war galleys of Spain. In an almost unbelievable turn of events, the Turks won, not only freeing many Muslim slaves on board the war galleys, but also picking up many moriscos who were trying to escape Spain. They took the captured ships with them back to Algiers.

The next year, Khizr decided that he was going to finally drive the Spanish out of their last stronghold in Algiers, that island fortress that had first beckoned them to the city in 1516. The Spanish had never fully abandoned it, despite the end of direct fighting in 1519. The siege began on May 6, 1530, and continued for fifteen days.26 Finally, the fortress fell, and the Spanish soldiers who survived were sold into slavery.

A few years later, in 1533, Khizr received an ambassador from Constantinople. The sultan, Suleiman, had invited him to come to the city for a meeting. Once there, he was tasked with reorganizing the Turkish fleet, which had fallen into disrepair. Some legends say that Khizr was actually responsible for telling Suleiman the Magnificent that whoever ruled the sea would rule on land as well.27 However, Suleiman had probably already figured this out himself—he could hardly miss how much wealth sea voyages had brought to Western Europe.

There was also the rumor that Charles V had been making overtures to Suleiman, asking him to step in and call off the attacks on European shipping.28 However, Khizr had no desire for peace with Spain—and in fact pushed for an alliance with France instead. He encouraged Suleiman to pursue that avenue instead, and the two powers eventually signed a treaty to work together. Though the treaty benefitted France in the short term, it infuriated a lot of European powers who saw an alliance with Muslims as a betrayal of Christianity. Clearly, the alliance didn’t last long.

Khizr spent his time in Turkey basically creating the Ottoman Navy. I mean, there was one already, but he made it an actual fighting force that could exert Ottoman supremacy in the Mediterranean. He made the navy efficient for the first time, bringing his knowledge from 30 years on the sea to improve their dockyard, their shipbuilding, everything. It was very necessary.

Soon after this, Khizr was offered the position of High Admiral of the Ottoman Navy. He officially went legit, serving Suleiman the Magnificent in this capacity for around 10 years. As the commander of the Ottoman Navy, Khizr recaptured several islands that had been taken by European powers. He raided enemy cities along the Greek and Italian coasts and generally fought Charles V at every turn. It’s worth noting, however, that Turkish militaries were not allowed to loot the cities they conquered the way that European militaries often did. As I mentioned earlier, the Ottomans especially had learned that a ruined city is a bad inheritance, so if they thought that they could capture and control a city, they did not also destroy it.29 Cities that were burned and looted by Turkish pirates or legit Ottoman soldiers were often attacked that way because they represented a stronghold of an enemy and there was little chance of taking and retaining power there. This is a very different practice than what we see in European militaries at this time, and even Catholic chroniclers noted how much better behaved the Turkish soldiers were. This often happened because European soldiers went out sort of on spec, they were only going to get paid if they were successful at raiding, whereas the Ottomans reliably paid their soldiers a salary.

The apex of Khizr’s legitimate career was on September 27th, 1538, when his Ottoman Navy defeated the combined fleets of Venice, Genoa, and the Pope in the Ionian Sea, off the island of Preveza. The victory gave Turkey control of the area for at least thirty years, and enabled Suleiman the Great to expand the bounds of the Ottoman Empire, creating a continuous kingdom from Persia to Algiers in the south.30 The anniversary of this victory is still a national holiday in Turkey, I believe, and is marked by a ceremony at his tomb.

In 1540, Charles V hired the old commander Andrea Doria and a rising star in the Spanish navy, Hernán Cortés, to once again lay siege to Algiers. As had happened in 1519, the planning stage took too long, and they left too late, and were basically defeated by bad weather. Khizr was not there at the time but had left his only son, Hasan, in charge. In fact, after Khizr left for Istanbul in 1535, he never returned to Algiers.

Khizr retired in 1545. He had spent some of his wealth building a palace on the Bosphorus, the strait in Istanbul that divides Europe and Asia. During retirement, he dictated his memoirs—they comprise five volumes. The title is usually translated into English as The Conquests of Hayreddin Pasha, or sometimes The Invasions of Hayreddin Pasha. They do not seem to have been translated into English, which is too bad. All told, the official count of his expeditions against Spain is totaled at 36, which seems very low to me.

In 1546, Khizr died in modern-day Istanbul. He is buried in a domed octagonal tomb near his palace, and outside of it stands an enormous marble statue, still looking toward the sea.

His legacy is a complex one, not just because of the confusion of the many names he has gone by. In Turkey, Khizr or Kheir-ed-Din Barbarossa has been the subject of uncountable books, movies, video games, and more. He has made it into European and American tales as well, his complicated reputation creating varied portrayals. Most recently, he was the inspiration for Barbossa in Pirates of the Caribbean, though I take issue with the way he was transformed into a Spanish pirate, given that he spent his life fighting the Spaniards. His story deserves another look and I hope we see a big-screen treatment of his tale soon.

If you liked this story, you will love my book, Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of. In fact, the story of Barbarossa, or Kheir-ed-din, touches on two chapters in the book—contemporaries of his whom he interacted with, made alliances with, and perhaps even rescued. It’s out March 5, 2024, but you can preorder it now wherever you get books. You can let me know your thoughts about this or any other episode on Substack, Twitter, and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it does help other folks discover the show.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Castellanos Clark. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email at hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com If you’d like to send us something, you can send it to P.O. Box 27162 Los Angeles CA 90027.

Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

Bradford, Ernle, and John Freely. The Sultan’s Admiral: Barbarossa: Pirate and Empire Builder. 2nd edition. London ; New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2009.

Carr, Matthew. “Spain’s Moriscos: A 400 Year Old Muslim Tragedy Is a Story for Today.” The Guardian, March 14, 2017, sec. Books. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/14/spains-moriscos-a-400-year-old-muslim-tragedy-is-a-story-for-today.

Commander E. Hamilton Currey. Sea-Wolves Of The Mediterranean, 1910. http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.173046.

Dee, Katherine. “The Myth of Gen Z’s Love for Osama Bin Laden.” UnHerd, December 30, 2023. https://unherd.com/newsroom/the-myth-of-gen-zs-love-for-osama-bin-laden/.

“Janissary.” In Wikipedia, February 24, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Janissary&oldid=1210038872.

Kalkan, Gökçen. “Memoirs of Khair Al-Din Barbarossa Its Truth, Importance and Historical Value.” Külliye 4, no. 2 (September 30, 2023): 398–411. https://doi.org/10.48139/aybukulliye.1322767.

Piccirillo, Anthony Carmen. “The Franco-Ottoman Alliance of Francis I and the Eclipse of the Christendom Ideal.” Georgetown University, 2009.

Tartakoff, Paola. “Expelled from Spain: July 31, 1492 | Exploring Hate | PBS.” Exploring Hate, July 26, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/exploring-hate/2022/07/26/expelled-from-spain-july-31-1492/.

Ernle Bradford and John Freely, The Sultan’s Admiral: Barbarossa: Pirate and Empire Builder, 2nd edition (London ; New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2009).

Bradford, 19

Bradford, 23

Bradford, 23

Bradford, 27

Bradford,

Bradford, 28

Bradford, 29

Bradford, 37

Bradford, 42

Bradford, 45

Bradford, 53

Bradford, 59

Bradford, 61

Bradford, 62

Bradford 68

Bradford, 75

Katherine Dee, “The Myth of Gen Z’s Love for Osama Bin Laden,” UnHerd, December 30, 2023, https://unherd.com/newsroom/the-myth-of-gen-zs-love-for-osama-bin-laden/.

Bradford, 81

Bradford, 84

Bradford, 97

Bradford, 97

Bradford, 99

Bradford, 78

Bradford, 115

Bradford, 113

Commander E. Hamilton Currey, Sea-Wolves Of The Mediterranean, 1910, http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.173046.

Bradford, 119

Bradford, 143

Bradford, xii

Share this post