Hey everyone,

I’m excited to bring you the tale of Alfred Carlton Gilbert, the Man Who Saved Christmas! If you’re celebrating Christmas this week, I hope you have a wonderful one. And if you’re not celebrating Christmas, I hope you have a wonderful week!

Don’t forget the Black Friday sale is still on—I’ve finally decided to close it this Sunday! This 50% discount is the absolute lowest price that a subscription has ever been. Don’t miss out. (It makes a great last-minute gift for a loved one, as well!)

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Castellanos Clark, and today I’m covering Alfred Carlton Gilbert. He was a toy inventor, an Olympic athlete, and often remembered as the man who saved Christmas.

But before we jump into Gilbert’s life and how he saved Christmas, I first have to thank all the paying subscribers on Substack who help me make this podcast possible. Y’all are the best and this podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! If you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber over on Substack! When you upgrade, you’ll get access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates on the upcoming Unruly Figures book. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

All right, let’s hop into it.

Alfred Carlton Gilbert, or as he preferred, A.C. Gilbert, was born on February 15, 1884, in Salem, Oregon. He was the middle boy in a family of three, but he wasn’t particularly close to either of his siblings. His parents fostered a religious atmosphere; according to his memoir they did devotions every morning and Sundays were solely dedicated to religious activity with neither work nor play allowed in the home. Gilbert, quote, “found it something of a strain, because [he’d] never been able to sit still very long.”1 Nevertheless, he described his home life as “the happiest home anyone could imagine.”2

Instead of being religious, young Gilbert was extremely active. At age seven he won a tricycle race, which apparently cemented his lifelong philosophy that, quote, “life is a game and the important thing is to win.”3 Often unimpressed by school and unconcerned with his grades, he collected friends, hobbies, and—it sounds like—messes. In his autobiography, he writes, “My mother’s attitude and fortitude were even more amazing... [she] just had to look on as I repeatedly tried to break my neck and cluttered up the house, yard, and barn with strange pets, athletic paraphernalia, the accessories of various hobbies, and a gang of friends.”4 He enjoyed all manner of sports, hunting, and building things on the family farm, including a play fire station for him and his friends.

One of his early hobbies was magic and sleight of hand. One of his favorite early memories was of a performance of Herman the Great, a traveling magician who he described as “on a par with…Houdini.”5 He became good enough that he used magic performances to earn money to pay his way through college. After graduating, he started a business that manufactured and sold magic tricks. Interestingly, he wasn’t the first in his family to be associated with magic—his very distant great-great-great, etc—it’s seven greats—grandmother was hanged for witchcraft in Wethersfield, Connecticut. He doesn’t state her name, but I took a quick glance at the list of people convicted of witchcraft in Connecticut’s history and found a Lydia Gilbert, who was, quote, “probably executed” in 1654, but in Windsor, Connecticut.6 There were only two women convicted and executed in Wethersfield—Mary Johnson and Joan Carrington, so perhaps one of them was Gilbert’s distant relation.

Okay, I know that’s a digression but I just find it fascinating when rebellious people have rebels in their family history. Is it a gene they’re passing down? Family socialization? One of Gilbert’s other ancestors also married Daniel Shays, of the famous Shays’ Rebellion during the US Revolution. Isn’t that weird?

Anyway! So Gilbert progressed through school, finding it easy but tedious. When he was 8, the family moved to Moscow, Idaho. Things were a bit unstable for a moment—they lived in Moscow for two years, moved back to Oregon for a year, and then back to Moscow when Gilbert was probably about 11 years old. Now, after this move back to Idaho, he famously ran away to be a performer.

It started like this: He’d put up a punching bag in the barn, and someone in town realized that he was pretty good at it. When a troupe came through town, someone in town mentioned to the manager that Gilbert was pretty strong, and the manager hired him at $15/week, which was a fortune for a young boy in the 1890s.

“I knew what my parents would say, so I didn’t ask them,” he said of the decision to leave town with the manager.7 He described the other men in the show as extremely nice so he felt safe and off he went. He traveled with them for about a week, and they put up posters with a drawing of Gilbert and the claim that he was “The champion boy bag-punchers of the world!”8 Fortunately, his father caught up with them and convinced him to come back, assuring Gilbert that a much more fruitful future than performing with a punching bag awaited him.

Now, a lot of people portray this as a very charming tale of a boy who ran off to join the circus. And it sort of is that, but I want to be clear that Gilbert was actually joining a minstrel show, that bastion of racist stereotypes. It’s unclear to me whether or not he actually performed in blackface, but his co-performers certainly did. In the 1950s, when he originally wrote his memoir, he didn’t seem bothered by this fact. Obviously today we find this a lot more distasteful, so I just want to be clear that that’s what’s happening here instead of sugar-coating it.

Back in Moscow, Gilbert saw people pole-vaulting for the first time at the University of Idaho. He picked up the new hobby immediately and became extremely good at it. Soon after, his older brother started university at Pacific University back in Oregon. After a year, Gilbert decided he wanted to move back to Oregon with his brother, so he saved up money he earned working on the railroad and enrolled at the university’s nearby preparatory school, Tualatin Academy.

Tualatin was a rare mixed-gender boarding school, and it was there that he met his future wife, then named Mary Thompson. Every night that she had choir practice, he would sneak out of his room past curfew to walk her back to her room. Perhaps unsurprisingly, her family pulled her out and they moved to Seattle after two years of this. But they stayed in touch and got married several years later, which I think is really sweet.

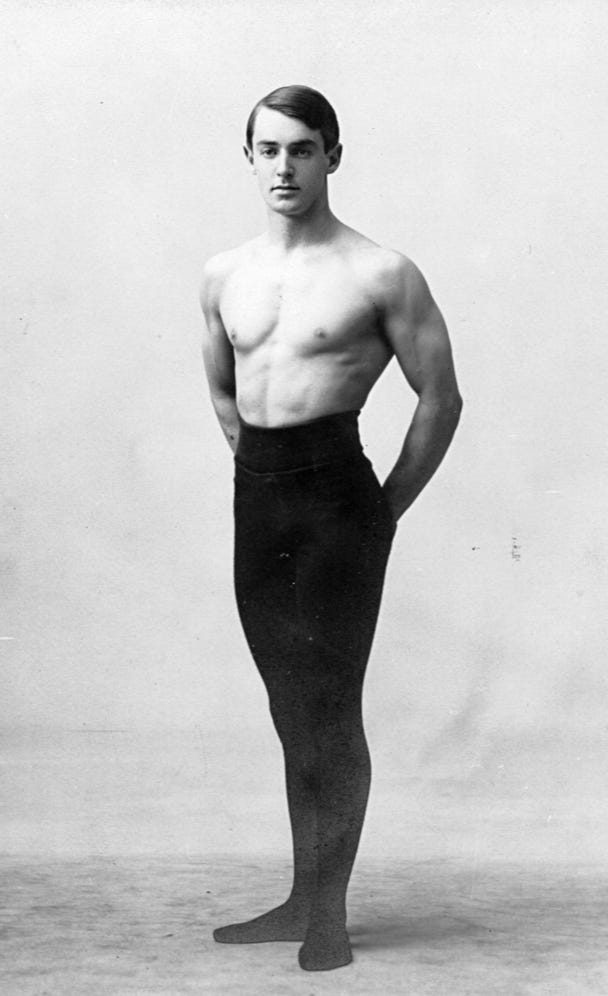

After graduating from Tualatin, Gilbert enrolled at Forest Grove, now called Pacific University. He studied a little harder than he had before, but was still more concerned with athletics. He won over a hundred trophies and ribbons while enrolled, mostly in boxing, wrestling, track and field, and football.9 He broke records, including the world chinning record—aka, pull-ups. The record had been 39 pullups, set in 1888 by N.W. Mumford, but Gilbert did 40 in 1901, when he was seventeen years old.10

While at the university, he started petitioning for a better gym; he had to travel down to Portland to go to the YMCA because the university didn’t really have a gym of its own. He also started coaching some boys on the wrestling team. All this athletic success led to him attending a summer term at the School of Physical Education in New York in 1902, which is where he befriended a bunch of doctors and decided to pursue a medical degree.11 In 1904, he transferred to Yale to study medicine and found himself intellectually challenged for the first time. He described his grades as “average” and had to give up most sports to keep up with his schoolwork.12

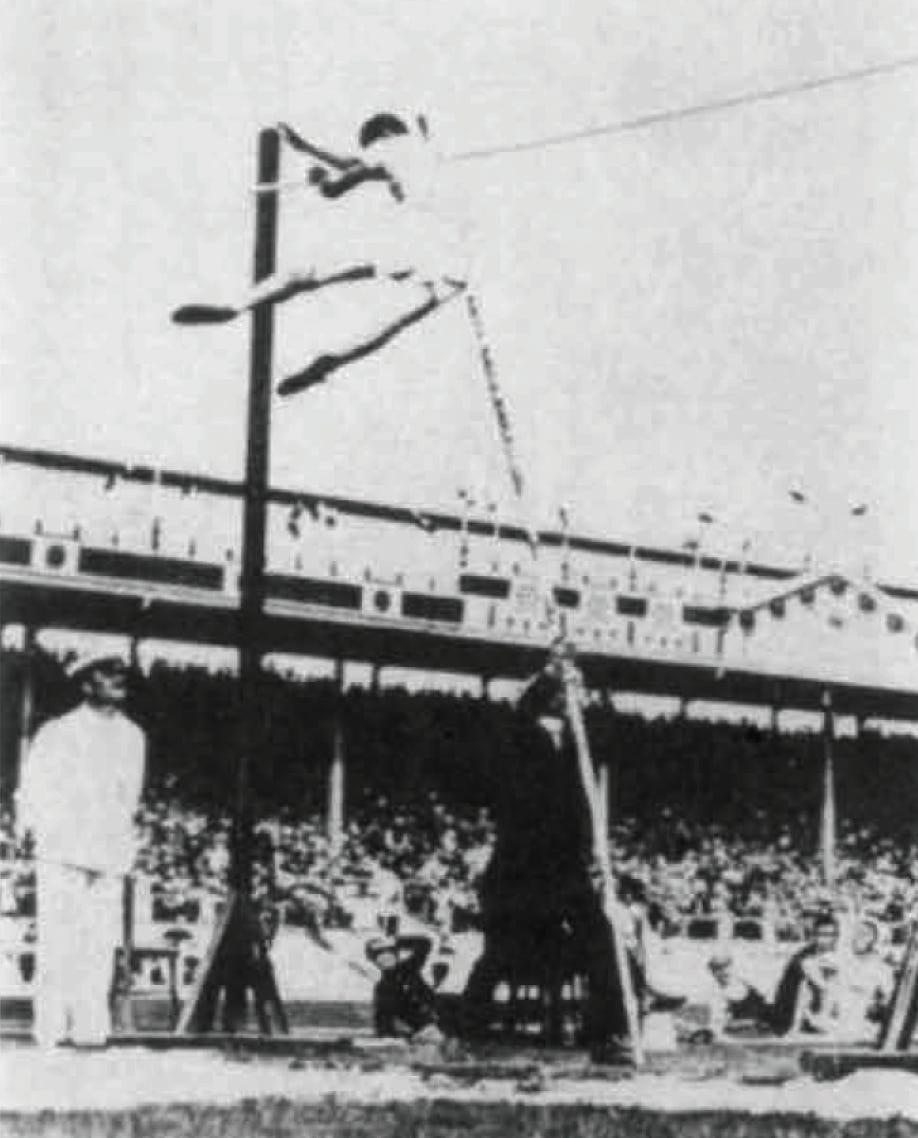

However, he kept up with pole vaulting setting several records while in school. In 1907, he took time off of his final year to train and travel down to Philadelphia to try out for the Olympics; he made it and was off to Brighton to train for the 1908 Olympic Games. He set a world record in try-outs, with a leap of twelve feet, seven and three-quarters inches.13

But there was a big debacle, and declarations of bad sportsmanship at the games that year. The night before the pole-vaulting competition, the English hosts had ruled that pole-vaulters could not use a hole in the ground for their poles, they had to use a spike instead—the English way. In fact, only the English pole-vaulters still used spikes, everyone else in the entire world used holes. Well, the English and one Canadian named Edward Archibald.

The American team took this as a blatant attempt to ensure Archibald won gold. So Gilbert went out early the next morning, bought a hatchet, and dug a hole himself, next to the spike. Well of course he was stopped and there was an attempt to disqualify him from the Games entirely. He demanded that the rules be read out loud, which someone finally complied with, and the rules made no mention of holes in the ground at all. I think he thought that would matter, but the English hosting committee had already decided and he was told he had to vault with a spike in his pole or not vault at all.

The event went forward. Gilbert did well, advancing through heats and eventually winning the finals. Well, but the judges had another plan—with a last-minute rule change that has never been enforced since, the judges said that in order to actually win, Gilbert had to beat out the highest recorded jump of the Games, which was twelve feet two inches, set by one of his teammates during prelims.14 He made it, so the judges decided that it didn’t count, it would only tie him with the guy who had jumped that high during prelims, despite the fact that that guy hadn’t even been in the top 3 in the finals. Suddenly he was co-winning gold with Gilbert. It didn’t make any sense.

So the judges set the pole to twelve feet, six inches, telling him he had to clear that if he wanted to win gold on his own. Which is ridiculous, that’s not how pole vaulting has ever been measured, as far as I know. It was blatant favoritism, I don’t think they could get away with this today. So of course Gilbert couldn’t actually clear that, not when he was vaulting with an unfamiliar spike that he said made him feel like he, quote, “didn’t know where [he] was when [he] took off, and [he] felt as awkward as a calf” in the air.15 The event was declared a tie for the first time in Olympic history—something which didn’t happen again until the 2021 Tokyo Olympics.16

Gilbert’s co-winner told Gilbert to go to the ceremony alone, which makes a lot of people think that Gilbert won the medal alone, but it is on record as a tie. He claimed in his memoir that the medal, quote, “must have carried a jinx, because it was stolen” when he got back to the US.17

In his memoir, Gilbert acknowledged that the whole ordeal stuck with him; he grew a bit bitter over it, it sounds. He was happy he won gold, but also never competed again. While traveling in Paris after the games, he bought 50 bamboo poles for $1.25 each and brought them back to New Haven. He sold them to colleges for $25 each, making about $1,100—that’s nearly $37,000 today. 18

After that, he finished school and married Mary Thompson. Despite receiving a medical degree, Gilbert apparently never put it to much use. In his fourth year at Yale, he had met John Petrie, who worked as a mechanic in a factory in New Haven; he was interested in magic tricks and had heard that Gilbert was paying his way through Yale with magic shows and teaching magic to kids. It was Petrie who had the idea to first box up some of Gilbert’s magic tricks into little kits with instructions and sell them to students; their business was born.19

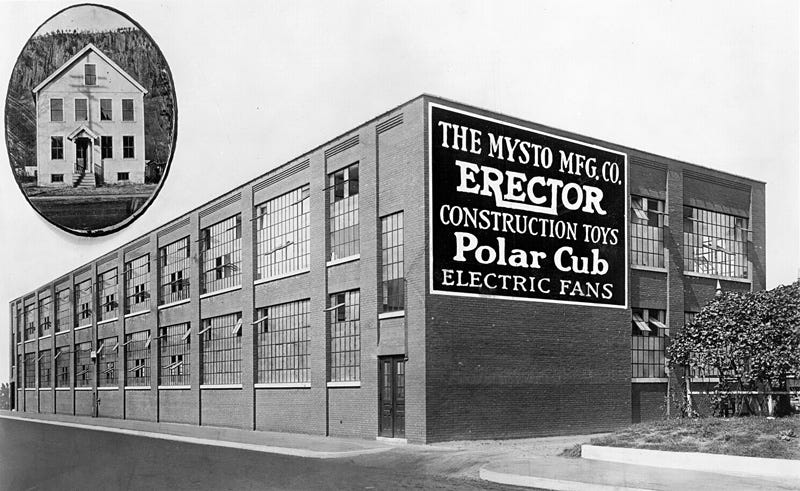

With the money he made from selling the bamboo poles, Gilbert invested in the idea that he and Petrie had, expanding into a mail-order catalog for professional magic tricks. They called it the Mysto Manufacturing Company, basing it in New Haven, Connecticut. In addition to his own money, his father loaned him $5,000 to help build a proper manufacturing facility. They started selling quite successfully, even opening a store in New York City at Twenty-Ninth and Broadway. Eventually, they developed hundreds of magic tricks and sold them around the nation, attracting both professionals and amateurs.

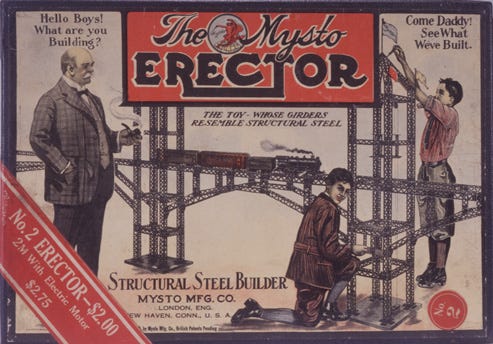

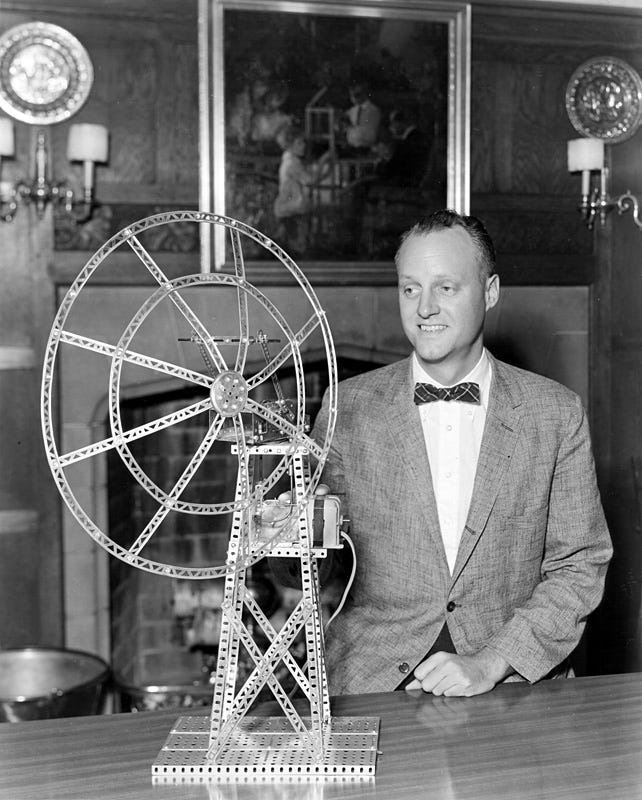

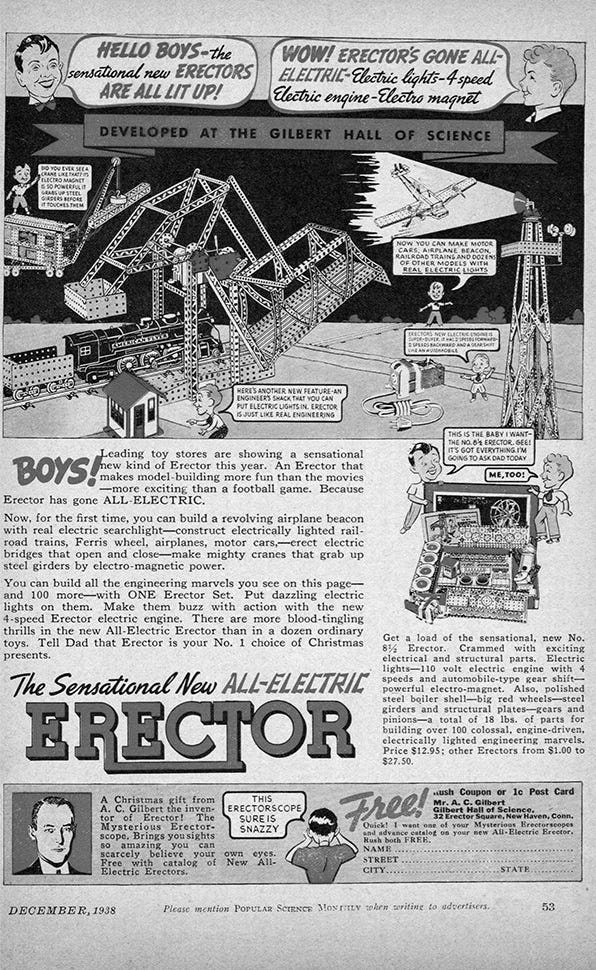

Not interested in coasting on his laurels, Gilbert began to think about making other toys. In 1911, he watched steel girders be lifted into place by cranes and had an idea—why not make toys for boys that allowed them to build new things? He developed, tested, and released the Mysto Erector Structural Steel Builder in 1913, which was quickly shortened to “Erector Set.” With it, boys could make hundreds of toys—there were ideas in an instruction booklet, but, quote, “the hope was that after a short while an inventive boy would start making his own things instead of just copying models from the manual.”20 It was a hit, becoming a household name in just a few years.21 This popularity was probably helped along by the fact that, at least according to Gilbert, the Erector set was the first toy ever advertised in a national magazine, instead of just through toy shops and catalogs.22 They sold for around $2 and featured boys building working train tracks on the box. There’s a photo of a box on Substack, for anyone interested.

The marketing slogan for the set was, quote, “Hello Boys! Make Lots of Toys.”23 Gilbert began hosting Erector building competitions, with certificates from the Gilbert Institute of Engineering going to participants and prizes going to the most impressive structures built using an Erector set. One year he gave away a German Shepherd puppy, and another a Shetland pony; I’m sure the kids were excited, but you have to wonder how excited the parents were about receiving a new mouth to feed.24

In 1915, the Erector set won a Gold Medal at the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

One of the challenges to making the Erector set—and many of the toys Gilbert would pioneer and produce—was that there was no manufacturing precedent for it. He often had to develop the machinery to make the toy at the same time that he had to develop the toy itself. There was machinery to make steel girders, of course, but not on a scale small enough to be played with by kids. I know very little about manufacturing, but I know enough to know how interesting and rare this is—today people can invent a new type of doll or building set, but there are precedents to making it. You can program a machine to cut the wood or pour plastic into a different mold; but when Gilbert was inventing, even the machinery wasn’t around yet.

Another pioneering idea of Gilbert’s was to emphasize child psychology in advertising his toys to adults. The 1914 booklet accompanying the Erector set read, quote,

Our new educational idea, which is the result of a study of child psychology, is developing a new angle of vision upon education. We find that the element of fun and pleasure has a wonderful effect in stimulating the inventive faculties which lie dormant in the child. Why not develop them in a sort of subconscious way?25

This focus on children’s learning would become an important part of Gilbert’s career.

Around this time, in 1912 or so, Gilbert’s father bought John Petrie out of his share of the company. According to Gilbert’s autobiography, there was no friction about this transition—Petrie was more interested in the magic side of the business, and he eventually spun off to run his own company focusing on professional magicians.26 However, I do wonder if it was just a coincidence that Gilbert waited until Petrie had died before putting out his autobiography. It might really have been smooth—Gilbert has only good things to say about Petrie in his memoir—but I guess there’s a chance that he waited to publish until he could be sure that Petrie wasn’t going to issue any statements about how amicable or not this split really was.

In any case, the Erector Set made Gilbert moderately famous, and the Mysto Manufacturing Company was renamed the A.C. Gilbert Company in 1916. On June 9th of that same year, Gilbert founded the Toy Manufacturers of America, which today still represents the interests of all companies associated with youth entertainment. Today, their mission is to be, quote, “the industry’s voice on the developmental benefits of play, promoting play’s positive impact on childhood development to consumers and media through our Genius of Play initiative.”27

Behind the scenes, Gilbert was working on sets of more explicitly educational toys, including chemistry sets and an electric experiment set. They wouldn’t be produced for several years while they worked out the kinks, but the idea was interesting right off the bat. What was also interesting was that Gilbert explicitly did not want these sets in school. Despite receiving okay grades, I guess his own education was a bad memory because he was afraid that if kids associated any of his toys with school, quote, “they’d think they were just as deadly dull as the rest of school and would have nothing to do with them.”28

But it was this interest in educational toys that led to his most infamous toy: his Atomic Energy Laboratory, sold in 1950. It has gone down in history as one of the most dangerous toys ever produced because it contained real, actual, honest-to-God, samples of “uranium-bearing ores (autunite, torbernite, uraninite, and carnotite.)”29 I wish I could say that it was all an innocent mistake, that no one knew uranium was dangerous yet—but first of all, the toy was sold with a comic strip called “Learn How Dagwood Splits the Atom,” written with General Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project.30 So clearly it was openly associated with the devastation of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. Second of all, the higher incidence of lung cancer among uranium miners had been noticed as early as 1879, and by 1930 people already suspected that uranium was the source of the problem.31 The kids who were gifted the Atomic Energy Kit might have learned a lot—the kit came with a Gieger counter, a Wilson cloud chamber, a spinthariscope, and an electroscope—but they were ultimately exposed to U-238, which has been linked with Gulf War syndrome, cancer, leukemia, and a host of other serious medical conditions.32

Interestingly, Gilbert says the US Government encouraged the company to make the toy.33 Gilbert writes, quote, “[the government] thought that our set would aid in public understanding of atomic energy and stress its constructive side. We had the great help of some of the country’s best nuclear physicists and worked closely with M.l.T. in its development.”34 On the one hand, I’m glad that M.I.T. was involved so it sounds like someone knew what they were doing; on the other hand, why were none of the country’s best nuclear physicists putting their foot down about the danger this toy posed?

Now, in his memoir, Gilbert makes an interesting and very carefully worded claim, so I’m going to repeat the full quote here: “There was nothing phony about our Atomic Energy Laboratory. It was genuine, and it was also safe. We used radioactive materials in the set, but none that might conceivably prove dangerous.”35 I find ‘might conceivably prove dangerous’ to be strange wording: It’s like they realized the risk and pulled the toy to avoid testing on whether or not it really was dangerous. As far as I know, there hasn’t been a study of the long-term effects of this toy on the children who got it, but I do think it’s telling that the toy was only sold for one year. Gilbert claims that this was an expense issue, that even priced at $49.50 they were taking a loss on the toy. He also notes that the toy wasn’t suitable for younger kids, which the rest of their line was aimed at. In fact, Columbia University bought 5 of the kits for their chemistry department—apparently it was well-suited to undergrads!36 They did, however, adapt some of the Laboratory to their largest chemistry kid, including supposedly “safe radioactive ore” as well as the manual and the spinthariscope.37 This last tool though is the proof that it was still dangerous though—a spinthariscope records “results of radioactive disintegration on a fluorescent screen.”38 The disintegration of the nuclear ore is the dangerous part!

According to an article in TIME, however, the toy was dropped after, quote, “a flood of protests” claiming that boys would actual atomic bombs with the kit.39 This claim does not make it into his memoir, either because Gilbert thought it was ludicrous or because he didn’t want to call attention to it. I have a feeling that it’s more the first issue—I don’t really believe kids could have made a real bomb with the kit.

Unfortunately for Gilbert, it seems to be this dangerous toy that the general public associates his name with most; this story is how I first learned about him. However! His epithet, the Man Who Saved Christmas, came several years before the release of his dangerous toy.

The year was 1917, and the US had finally entered World War I in April. The National Council of Defense converted factories of all stripes to aid in the war effort, including some of Gilbert’s toy factories. However, the National Council of Defense also shut down all “nonessential” manufacturing in order to preserve materials for the war effort; this ban included many toy factories. Overnight, companies became worried that they’d go out of business, ruining Christmas for American children. The Council told parents to buy Liberty bonds for their children instead, but let’s be honest: what kid understands a war bond well enough to get excited about one for Christmas?40

Gilbert, as the President of Toy Manufacturers of America, protested this restriction. Somehow, he managed to get a fifteen-minute meeting with the Council, so they went to Washington to present their case. Instead of making an impassioned speech or giving the members of the Council numbers, Gilbert gave them toys. Behind closed doors inside the Navy Building, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane, and Secretary of Commerce William C Redfield got down on the ground and played with Gilbert’s toys while he explained to them the educational value that toys had. Quote,

The greatest influences in the life of a boy are his toys. A boy wants fun, not education. Yet through the kind of toys American toy manufacturers are turning out, he gets both. The American boy is a genuine boy, and he wants genuine toys. He wants guns that really shoot, and that is why we have given him air rifles from the time he was big enough to hold them. It is because of toys they had in childhood that the American soldiers are the best marksmen on the battlefields of France. America is the home of toys that educate as well as amuse, that visualize to the boy his future occupations, that start him on the road to construction and not destruction, that as fully as public schools or Boy Scout system, exert the sort of influences that go to form right ideals and solid American character.41

It worked. The Council backed off of their ban on toy manufacturing. Apparently Redfield was, quote, “enamored with a steam engine saying ‘I learned the rudiments of engineering on an engine like this.’”42

When he was lauded in the press for saving Chrismtas for America’s children—the full text of an article from the Boston Post has been transcribed into his memoir—Gilbert turned down praise, saying, “The toys did it.”43

Nevertheless, the majority of Gilbert’s factories were turned over to the war effort. They made parts for machine guns and gas masks, but to Gilbert the most important part was making Colt .45s as part of a subcontract from Winchester.44

After the war, the educational kits finally went on the market. They were a huge success, and a Yale professor would later claim that 70% of his students became interested in science through an A.C. Gilbert kit.45 Gilbert also started focusing on a radio set, known then as a crystal set. In 1928, Gilbert’s toy company sponsored the first sports broadcast ever heard on national radio, and he was the master of ceremonies. He interviewed several celebrity athletes, including Babe Ruth. There’s a photo of that on the Substack as well.

Throughout this time, Gilbert’s wife Mary was raising their three children, though you wouldn’t know the kids existed from his autobiography. Gilbert used his downtime to breed German Shepherds and hunt, seemingly only rarely spending time with his family. He built an enormous estate near New Haven that he named Paradise; he used it to hunt. Though he claims in his autobiography that he has left out his family in a bid for privacy, it comes off as a little egomaniacal, especially since the book is named after his home but his home life is otherwise absent. The final pages of the book include a list titled “Notable Events in the Life of A.C. Gilbert;” his wife and children are not mentioned at all.

Somehow, Gilbert found time to help with the Olympic Games in 1928, 1932, and 1936. He was no longer competing as an athlete, but he went along as the Chef de Mission of the team; basically, it seems like he was in charge of morale and making sure everyone behaved. The ‘36 Games caused quite a lot of controversy, as they were being held in Berlin. Hitler had come to power after Berlin was chosen for the Games, and with his persecution of Jewish people living in Germany already underway, a lot of teams were in favor of protesting the Olympics. However, Gilbert insisted that they should go, acknowledging in his memoir that he was somewhat against the tide with that opinion. It doesn’t seem like he was anti-Semitic though—he assays that he believed American attendance would, quote, “put the Germans on their best behavior.”46 He thought that if the US protested, they’d be just as bad as the Germans who were persecuting Jewish people. Honestly, I’m really surprised that he included this opinion in his autobiography. The attendance of national teams like the US legitimized the Nazis; many people think that the world kind of learned its lesson after the full human rights abuses of the Holocaust were revealed, and the mistakes made in 1936 led to the Olympic boycotts of 2008 and 2014.47

I’m even more surprised that he included this statement too: “I must say right now that the games were conducted as well as they have ever been, to my knowledge, and in the opinion of many Olympics officials. The German people were kind, considerate, and understanding. The German judges were scrupulously fair.”48 While the organization of the Games was lauded by a lot of people, it’s ridiculous to call the judges fair—many cited German favoritism leading to Germany winning the lion’s share of medals that year. Honestly, this just feels like a dig at the 1908 Olympics. Like I said, Gilbert remained bitter for the rest of his life about the blatant favoritism from the English judges when he competed. It was a poor choice on his part to let his bitterness blind him to the reality of what was going on in 1936, but he isn’t the first or last person to allow themselves that kind of blindness.

Most biographies of Gilbert sort of peter out around 1938. He bought the rights to the American Flyer trains that year. He kept inventing toys, including, in 1950, the infamous Atomic Energy Lab that I mentioned earlier. During his lifetime, he would eventually hold 150 patents.

I do want to note that Gilbert was a pretty good employer for the time. He is often credited with being one of the first employers in the US to offer maternity leave as well as free legal advice for employees; some try to claim he was the first employer to offer benefits, but that sounds like too broad of a claim for me to confidently repeat it; how does one measure “benefits”?49 There are, however, some indicators that maybe Gilbert stopped being as generous as he got older; despite the company making millions per year, there are reports that floor workers in the factory weren’t paid well.50

Nevertheless, at least at one point Gilbert was explicitly concerned about worker satisfaction and wanted them to have, quote, “the security of steady employment, as well as good wages and pleasant working conditions.”51 But according to his memoir, 90% of the Gilbert Company’s business was done leading up to Christmas, and there were usually a few weeks a year in January when they couldn’t start manufacturing toys yet because they’d run out of places to store them for 11 months.52 So instead of laying off his workers and then rehiring them, which was obviously a pain for everyone, the workers especially, Gilbert explicitly sought to invent something that could be sold in the summer, so there would still be work to do in January but the factories would still be able to run for the Christmas sales. He created a small, electric fan and sold it for $5, a huge savings over what was on the market at the time. So in that way, he was able to retain employees year-round, giving them a little more security.

Obviously today there would be other ways around this drop in production—machine maintenance, vacation, better storage, more year-round toy-buying anyway—but I think it’s really interesting that Gilbert was explicitly thinking about this stuff in the 19-teens, which if you know much about labor history then you already now it was not a particularly good time to be a blue-collar worker in factories in the US.

And then one more note here—in order to make those fans inexpensive and lightweight, Gilbert and one of his employees, an engineer named John Lanz, made the first successful enamel-coated wires. Other manufacturers had tried but had failed; Gilbert and Lanz were the first to do it successfully. Insulating the wires this way protects them and makes them thermal and chemical resistant. Today, enamel-coated wires are still used.

In 1954, Gilbert retired. His son Albert Jr. became the CEO of the company. This was perhaps not the best decision; Albert Jr. was not close to his father and really only ever worked in the family business to please him.53 Gilbert, on his part, didn’t do a lot of successor-planning, and so Albert Jr. wasn’t ready to take on the business; he was an engineer and an intellectual, not a businessman. As soon as Gilbert died in 1961, Albert Jr. sold the family’s remaining shares in the company to a man named Jack Wrather. The company went out of business just a few years later.

On January 24, 1961, Gilbert passed away after two heart attacks. His legacy remains strongly aligned with athletics and children’s toys; a museum in Salem, Oregon is named after him. In 2002, a TV movie starring Jason Alexander, of Seinfeld fame, was made to dramatize the 1917 winter when Gilbert earned his place in history books as the man who saved Christmas.

That is the story of Alfred Carlton Gilbert! I hope you enjoyed this episode. If you’re celebrating Christmas this weekend, merry Christmas, and if you’re not, have a lovely week/weekend. You can let me know your thoughts on Substack, Twitter, and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it really does help other folks discover the podcast.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Clark. My research assistant is Niko Angell-Gargiulo. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email at hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com If you’d like to send us something, you can send it to P.O. Box 27162 Los Angeles CA 90027.

Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

“$1,100 in 1908 → 2023 | Inflation Calculator.” Accessed December 17, 2023. https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1908?amount=1100.

“Alfred Carlton Gilbert.” In Wikipedia, August 25, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alfred_Carlton_Gilbert&oldid=1172157681#Personal_life.

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. “World’s Most Dangerous Toy? Radioactive Atomic Energy Lab Kit with Uranium (1950).” Accessed December 19, 2023. https://thebulletin.org/virtual-tour/worlds-most-dangerous-toy-radioactive-atomic-energy-lab-kit-with-uranium-1950/.

“Erector Sets | The Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop.” Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.eliwhitney.org/museum/-gilbert-project/-collections/erector-sets.

Gilbert, A.C., and Marshall McClintock. The Man Who Lives in Paradise. Second. Park City, UT: Silver Dollar Press, 2014.

Jhones, Micheal. “VERY BAD TOYS.” Radar Magazine, July 24, 2006. https://www.radarmagazine.com/features/2006/12/toys-print.php.

Norman-Eady, Sandra, and Jennifer Bernier. “Connecticut Witch Trials and Postumous Pardons.” Connecticut Office of Legislative Research, December 18, 2006. https://www.cga.ct.gov/2006/rpt/2006-R-0718.htm.

“Once Upon a Mine: The Legacy of Uranium on the Navajo Nation | Environmental Health Perspectives | Vol. 122, No. 2.” Accessed December 19, 2023. https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.122-a44.

Terrell, Ellen. “A.C. Gilbert’s Successful Quest to Save Christmas.” The Library of Congress: Inside Adams (blog), December 14, 2016. //blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2016/12/a-c-gilberts-successful-quest-to-save-christmas.

The Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop. “The Demise of The A. C. Gilbert Company.” Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.eliwhitney.org/museum/-gilbert-project/-man/a-c-gilbert-scientific-toymaker-essays-arts-and-sciences-october-6.

The Toy Association. “About Us.” Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.toyassociation.org/ta/about-us/toys/about-us/about-us.aspx?hkey=bb3f1cbf-1e1a-4d32-a809-02ba310c1c89.

TIME. “TOYS.” February 3, 1961. The TIME Vault.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The Nazi Olympics -1936 Berlin Olympic Games.” In Holocaust Encyclopedia. Washington, D.C.: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, August 22, 2023. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-nazi-olympics-berlin-1936.

Vorachek, Pamela. “Alfred Carlton Gilbert (1884-1961).” In Oregon Encyclopedia. Oregon Historical Society, March 16, 2023. https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/gilbert_alfred_carlton_1884_1961_/.

Willman, Howard. “Olympic Men’s High Jump — Fit To Be Tied.” Track & Field News (blog). Accessed December 17, 2023. https://trackandfieldnews.com/article/olympic-mens-high-jump-fit-to-be-tied/.

A.C. Gilbert and Marshall McClintock, The Man Who Lives in Paradise, Second (Park City, UT: Silver Dollar Press, 2014).

Gilbert, 22

“TOYS,” TIME, February 3, 1961, The TIME Vault.

Gilbert, 9

Gilbert, 18

Sandra Norman-Eady and Jennifer Bernier, “Connecticut Witch Trials and Posthumous Pardons” (Connecticut Office of Legislative Research, December 18, 2006), https://www.cga.ct.gov/2006/rpt/2006-R-0718.htm.

Gilbert, 22

Gilbert, 23

Pamela Vorachek, “Alfred Carlton Gilbert (1884-1961),” in Oregon Encyclopedia (Oregon Historical Society, March 16, 2023), https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/gilbert_alfred_carlton_1884_1961_/.

Gilbert, 50

Gilbert, 53

Gilbert, 59

Gilbert, 76

Gilbert, 81

Gilbert, 81

Howard Willman, “Olympic Men’s High Jump — Fit To Be Tied,” Track & Field News (blog), accessed December 17, 2023, https://trackandfieldnews.com/article/olympic-mens-high-jump-fit-to-be-tied/.

Gilbert, 82

“$1,100 in 1908 → 2023 | Inflation Calculator,” accessed December 17, 2023, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1908?amount=1100.

Gilbert, 71

Gilbert, 107

Vorachek

Gilbert, 107

Vorachek

Vorachek

Gilbert, 104/112 (the numbering in the book is messed up; it says 104, but it’s the second page 104)

Gilbert, 104

“About Us,” The Toy Association, accessed December 19, 2023, https://www.toyassociation.org/ta/about-us/toys/about-us/about-us.aspx?hkey=bb3f1cbf-1e1a-4d32-a809-02ba310c1c89.

Gilbert, 104/112

“World’s Most Dangerous Toy? Radioactive Atomic Energy Lab Kit with Uranium (1950),” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (blog), accessed December 19, 2023, https://thebulletin.org/virtual-tour/worlds-most-dangerous-toy-radioactive-atomic-energy-lab-kit-with-uranium-1950/.

World’s Most Dangerous Toy?

Micheal Jhones, “VERY BAD TOYS,” Radar Magazine, July 24, 2006, https://www.radarmagazine.com/features/2006/12/toys-print.php.

Jhones

Gilbert, 269

Gilbert, 269

Gilbert, 269

TIME, 76

Gilbert, 270

Gilbert, 269

TIME, 76

Vorachek

Ellen Terrell, “A.C. Gilbert’s Successful Quest to Save Christmas,” The Library of Congress: Inside Adams (blog), December 14, 2016, //blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2016/12/a-c-gilberts-successful-quest-to-save-christmas.

Terrell

Gilbert, 119

Gilbert, 121

TIME, 76

Gilbert, 210

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “The Nazi Olympics -1936 Berlin Olympic Games,” in Holocaust Encyclopedia (Washington, D.C.: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, August 22, 2023), https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-nazi-olympics-berlin-1936.

Gilbert, 210

“Alfred Carlton Gilbert,” in Wikipedia, August 25, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alfred_Carlton_Gilbert&oldid=1172157681#Personal_life.

“The Demise of The A. C. Gilbert Company,” The Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop, accessed December 19, 2023, https://www.eliwhitney.org/museum/-gilbert-project/-man/a-c-gilbert-scientific-toymaker-essays-arts-and-sciences-october-6.

Gilbert, 107/115

Gilbert, 107/115

“The Demise of The A.C. Gilbert Company”

Share this post