Hey everyone,

I’m so excited to bring you the story of Lillian Smith today. To be honest, this was a strange one. I started out thinking I was going to cover Annie Oakley, only to realize that this woman’s story needed telling more. Lillian’s story doesn’t have the usual heroic arc—and in fact some of you might feel she behaved very badly indeed—but I think it encapsulates this moment when our fantasies of the American West were being formed, and how easily they could have gone in a different direction.

I hope you enjoy this episode. If you do, I hope you’ll share it with at least one friend!

🎙️ Transcript

Stories of the American West conjure up images of cowboys, shootouts, and saloons. Much of our imagination was fed by touring shows claiming to depict the authentic West, like Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. But the actors in these shows portrayed a romanticized and often whitewashed version of the West, actually concocting stereotypes as much as they were doing what audiences expected. But what happened to the actors who didn’t quite fit in with the stereotype the rest of America was forming?

Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Castellanos Clark, and today I’m covering the tale of Lillian Smith, a sharpshooter and trick rider from the American West. She was known in her youth as the best female sharpshooter ever, and yet she was forgotten in her time and after in favor of another famous woman with a gun: Annie Oakley.

Before we jump into the tale of women in the Wild West, I first have to thank all of the paying subscribers on Substack whose patronage helps me make this podcast possible. This podcast wouldn’t still be going without you! If you like this show and want more of it, please become a paying subscriber over on Substack! When you upgrade, you’ll get access to exclusive content, merch, and behind-the-scenes updates. When you’re ready to do that, head over to unrulyfigures.substack.com

All right, let’s hop into it.

Lillian Frances Smith was born on August 4, 1871. As with many folks born before standardized birth records were a thing, we’re not 100% sure this is her birth date—in fact, her gravestone lists the day as February 3, 1871, though that could have been fudged to create the dramatic coincidence of having died on her birthday. But, I’m getting ahead of myself.

She was born in California, to a white Quaker couple from New England: boatbuilder Levi Smith and wife Rebecca. I want to make it very clear that she was not Sioux or of any other Indigenous American ancestry. There’s some crossing of racial boundaries that happens later in her life, which has resulted in some confusion. But we know her ancestry pretty well—her sixth great-grandfather, John Smith, was an indentured servant on the Mayflower and the descendants had lived in the northeast ever since.1 So let’s get that out of the way now.

The family had moved West post-Gold Rush, when California was already a state. They settled near San Francisco, in a town called Los Banos. But despite being near a bit city, the “taming” of the West was still underway, and between wild animals and conflicts with Indigenous tribes, everyone had to learn to shoot for safety and food. Lillian’s father, Levi, became a commercial hunter of ducks and geese who flocked to the valley. He was credited with inventing the “live blind” method of hunting, which involved a trained animal shielding a hunter while they stalked prey.2 Though it was an effective method, it was treated derisively at the time by hunters who prized a sort of integrity and fairness in hunting. They disliked it because it worked “without the previous knowledge on the part of the geese of danger’s proximity.”3 They called it an “undue advantage.”4

But for the family that hunted for a living, this was unimportant. Levi later invented or innovated several other methods of hunting, and Lillian was often along for the ride. Throughout her childhood, she helped her father hunt either by springing traps with him, keeping his guns loaded, or (as she got older) shooting with him. Levi had a natural talent for it, and she seems to have inherited that in addition to the training he gave her and his other children.

On hunting trips, Lillian might have had contact with the Yokut tribe, who lived in the central California valley. Though their population was swiftly declining due to changing migration patterns of fox and deer, as well as conflicts with white settlers, a few hundred Yokuts still camped near Lillian’s home growing up. Later, Lillian claimed that as a child she had learned to build a boat of wood and tule reeds by watching how the Yokuts baked tule reeds in the sun to create watercraft.5

In 1881, when she was just 9 or 10 years old, Lillian began shooting in venues for sport—or at least, that’s when we first start to see newspaper accounts of it. She probably started training a little earlier to travel with her father that summer while the birds he usually hunted migrated north out of the central coast droughts.

She was immediately a sensation. The Sacramento Record-Union reported,

“Santa Cruz county has a shooting prodigy in the person of Lillian F. Smith, a 10-year-old girl who lives near Corralitos. She recently gave an exhibition of her skill at Watsonville, and astonished the oldest sportsmen… She repeatedly broke balls thrown by hand into the air, hit two cent pieces that were thrown up, and did other wonderful shooting.”6

Most people were awed by her feats especially as compared to her stature and age. She was short, even for a child, but she was calm under pressure and her demeanor was so “perfectly cool” that it was “somewhat jarring in comparison with the violence of her performance.”7

In July 1881, Levi approached Robert Woodward, owner of a premier amusement park in San Francisco, Woodward Gardens. It featured a zoo, roller skating rink, and art gallery, as well as brought in performers and curiosities from all over the world. However, the word “curiosities” always makes me nervous—usually, these are people being put on display and not living good lives.

Lillian made her debut at Woodward’s on July 23, 1881. She appeared for two weeks and was an absolute sensation until she went back to school in mid-August. She continued on in this way, appearing up and down California throughout the summers, sometimes in shows, sometimes in shooting competitions. As she got older, her reputation so far preceded her that she was rarely allowed to compete against other teens and sometimes not even against full-grown men. When she was allowed to compete, she usually won, and prizes were usually between $100 and $500 each, which is roughly $3,000 to $16,000 today.8

In August 1885, Levi issued a challenge of a $1,000 to $5,000 purse for anyone who could beat Lillian in a rifle shooting competition, but apparently no one took him up on this. Perhaps no one thought he had the money. Perhaps no one else could afford the bet—$1,000 then is like $32,000 today.9

It’s worth noting that this is about when a conservation movement in California started to pick up steam. Wholesale slaughter of water fowl the way the Smith family had been relying on was starting to be frowned upon. And so the family began to spend more time at shooting matches than hunting, and it seems as if they were relying on Lillian’s prize winnings for income more and more. Levi pushed Lillian to learn increasingly complicated tricks, like shooting over her shoulder by sighting her target with a hand mirror, or skating so she could shoot while moving.

It’s also worth noting that, despite learning to shoot from her father, Lillian never gave him any credit publicly. She noted that her brother had been good at it, which inspired her, but never acknowledged her father’s contribution, which seems telling.10 This feels a little like the 1880 version of Dance Moms or any other backstage parents who rely on their child’s performance income.

But things were about to change for them. In spring 1886 in San Francisco, Lillian met William Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill. He was touring his play The Prairie Waif, and was getting ready to reformulate his Wild West show. He saw her perform and hired her immediately, and on April 20 she opened with an exhibition in North Platte, Nebraska, at Lloyd’s Opera House. Just fifteen years old, she was an immediate hit, and the Cody knew he had found a star.

Around this time she began to be known as the California Girl. Cody used it in his promotional material and when the Wild West show opened in May 1886, Lillian was considered one of the best features of the show. While this was great for her in terms of ticket sales, it opened the door to the rivalry that made her famous: Lillian Smith versus Annie Oakley.

Annie Oakley was also a member of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show at the time. She had joined the year before as his only female performer, which had vaulted her to stardom. But her success was her downfall—the female sharpshooter was so popular it encouraged Cody to hire more women. Oakley felt threatened by Lillian Smith’s appearance—as well as two cowgirls Cody hired at the same time to put on pony races. Lillian’s biographer Julia Bricklin speculates that there was probably never a chance of the two women becoming friends—”Annie would have been insulted and made suspicious by the addition of any female shooter,” she writes.11

Oakley’s immediately dislike of Lillian was probably not helped by the fact that Cody was not known for his tact. Again Bricklin writes, quote, “Cody had a tendency to acquire ‘shiny things’ in the form of immensely talented people, withoug giving immediate thought to how to manage their expectations and how to praise each performer for his or her unique contribution.”12 Some even think Cody probably encouraged the animosity because a rivalry brings in viewers, though in reality their animosity mostly stayed out of the papers and was only revealed later. Also encouraging it was Lillian’s father, who was traveling with the show, and may have been the source of the line “Annie Oakley was done for” now that Lillian had joined the troupe; this is often reported as Lillian’s line, though no one can corroborate it except Annie Oakley’s diary.13

But certainly, the two had opposing personalities that made camaraderie difficult, Annie Oakley had become famous with good shooting and a prim and proper reputation. She was seen as a Victorian lady who happened to be a very good shot, and she later encouraged women to pick up shooting to protect themselves and to spend more time with their husbands. With an Annie Oakley performance, shooting wasn’t sexy, it was a skill.

It became a bit sexy for Lillian Smith. She was flirtatious and entrancing. As she aged, her father not only marketed her name widely but also encouraged her to perform in more provocative outfits. I mean, provocative for the 19th century—she was still fully covered, with maybe some calf showing or a tight bodice. In her diary, Oakley wrote that “[Cody] saw both [Lillian’s] work and her ample figure” and cut Oakley’s salary in half.14 This is probably not actually why Oakley’s salary was cut—money was always tight with Cody—but she certainly blamed Lillian’s popularity with men for her loss.

All of this was probably enough to make Annie Oakley jealous and bitter. What made it worse was that Lillian was just better than her. She was a more sure shot, she missed less often, she could do more complicated tricks. And crowds noticed—people immediately began comparing them and finding Lillian Smith on top, often commenting on how young Lillian Smith was to be so good at this. Annie Oakley, well into her twenties by then, “lopped 6 years off her age” to try to compete.15

Smith was more or less unaware of Oakley’s jealousy and chagrin—at least at first. That first year, she was consumed by the pace of training and the performance schedule. She was also busy falling in love.

In June 1886, the Wild West Show settled on Staten Island for a summer of shows. The camp grounds were a welcome relief from the train cars they’d been traveling in every few weeks, and staying in one place led to a more stable income for the performers because Cody didn’t have to pay for expensive travel for the 200 people involved.

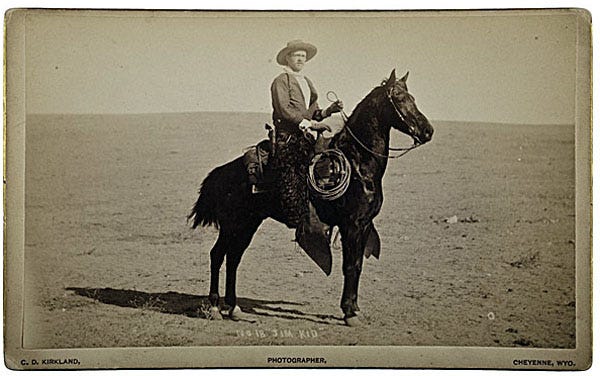

While at the camp, Lillian fell in love with James “Jim Kid” Willoughby, a champion rider and roper who was fourteen years her senior. Her parents were furious about this relationship—not because of the age difference, it seems, but because they thought that starting a family would be the end of Lillian’s career. Even if she did manage to stay in show business, her earnings would become Willoughby’s if they married. Her parents forbid her from even seeing him, but the two managed to sneak around camp easily, and finally secretly wed just as the show was ending and the camp was packing up.

However, neither had the courage to tell her parents, and her family apparently learned about it when they read a newspaper article titled “A Marriage in Camp.”16 It’s unclear what happened next, but we can bet the family was furious. It seems that they separated for a while, Lillian traveling with Willoughby and her family perhaps returning home to California. The next year, when Cody managed to secure the Wild West Show performances in London as part of the American Exhibition, Lillian and Willoughby traveled together.

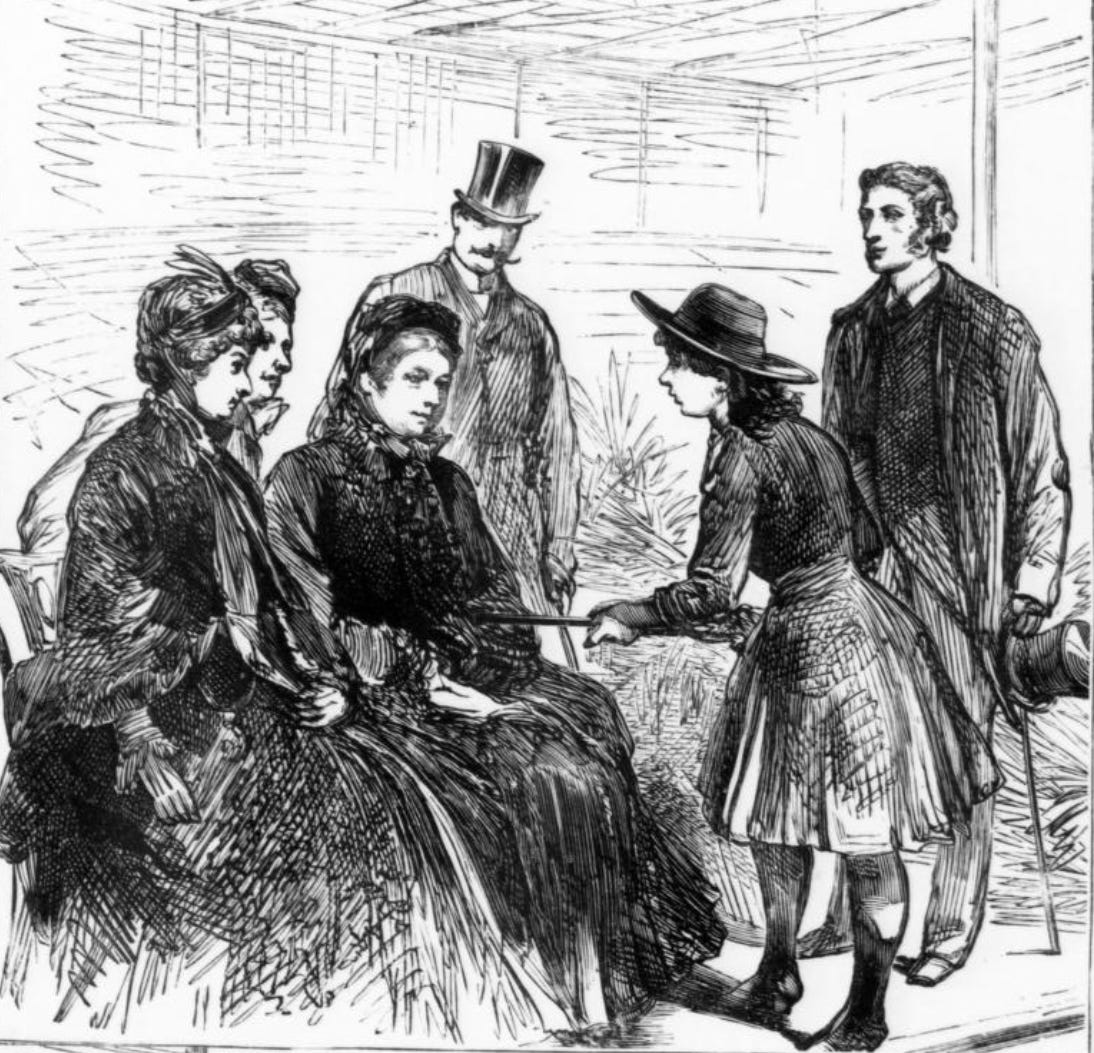

When the show opened on May 9, 1887, ten thousand people “stampeded past the main exhibition” to secure seats for the Wild West show.17 It was such a sensation that just two days later, Queen Victoria attended a command performance and was reportedly so enthralled with it that she requested that both Lillian Smith and Annie Oakley join her after, where she complimented their “dextrous performances.”18 A couple weeks later, The Illustrated London News ran a drawing of Lillian showing the queen how her gun worked.19

This riled back up the rivalry between Oakley and Smith. That summer, supposedly anonymous sources trashing and lauding the women in turn were published in hunting magazines—the reality was that it was probably Lillian, Willoughby, and Oakley’s husband Frank Butler. As the summer wore on, it became clear that Oakley was a society favorite as much as she was a shooting favorite—she was polished and proper, and clearly used to being in the spotlight and mixing with upper class people. Lillian had had no such education or training and missed out not only on networking and meeting new people but also sponsorship opportunities.

But the rivalry seemed to be coming to a close. The Wild West show played in London until October 31, 1887, and Annie Oakley left the show immediately after. Lillian Smith stayed on, joining the show in Birmingham and Manchester through spring of 1888 then back to Staten Island for another summer of the show in New York. They went back on tour through the fall, but when the show came to its seasonal close in October 1888 and contracts were being signed for the 1889 season, Lillian Smith was out and Annie Oakley was back in.

The terms of the contract have never been disclosed, but most people assume that Annie Oakley said she’d only come back if Lillian was dropped.20 She had been touring on her own, which was proof not just that people would come to see Annie Oakley shoot, but that she was the bigger star. That said, there’s also the possibility that Annie Oakley was picked because the show was going to Paris for the centennial of the French Revolution and she just fared better in Europe, where her more conservative dress and manner were preferred.

So while the Wild West show went to Europe in 1889, Lillian went back home to California. Unfortunately her husband was in Paris, and she ended up breaking off their relationship while they were separated. Back with her family, she was able to shake off some of the rules that she’d been hemmed in by on the East Coast; the western states and territories did not have the same strict social codes and class distinctions and so there was more opportunity for Lillian there.

For example, Lillian was sought after as a teacher for women and children who wanted to learn to shoot as a wholesome family sport. This was part of a turn in Victorian family values, which encouraged women and children to “share men’s outdoor pursuits as a way of upholding, rather than undermining” the family, which should be the center of all life.21 She also showcased her talents in big cities, where she would shoot in exhibtions, and was often enlisted by wealthy surveyors to help hunt for them and protect them from wild animals as they went out into the wild to survey land.

In the mid-1890s, Levi—who was back in control of Lillian’s life and money now that she was separated from her husband—Levi signed her up for “grueling rounds of vaudeville appearances.”22 In 1895, for instance, she spent several months at the Orpheum in Los Angeles, where her performances were “clever” according to the LA Times.23 While there she challenged other sharp shooters to one-on-one competitions for money, but none of these seem to have panned out.

However, compared to the high of the Wild West show and performing for the queen of England, things were clearly getting boring in the real west. Perhaps to have someone to travel with—and drink with and shoot with—Lillian married Theodore Powell, a football player for Santa Cruz’s new team, in 1897. It was reported by the Fresno Republican but doesn’t seem to have lasted long; within a few years Powell was remarried and working as a bartender in San Franscisco. Lillian’s multiple failed marriages have often been compared to Annie Oakley’s single successful marriage, shaming Lillian while also uplifting Oakley’s reputation as a proper wife as well as a proper lady.

In about 1898, things were turning for Lillian. Her career was on the verge of petering out—so much of her early fame had been about her youth compared to her skill and her rivalry with Annie Oakley. But once she was in her mid-twenties, her age wasn’t as impressive, and Annie Oakley was often a continent away, ignoring Lillian’s existence. And then she met Charles Hafley.

Hafley was the sheriff of Tulare County, in central California—or he had been until he served in the Spanish-American conflict. He returned to the area to find he had been replaced at around the same time that Lillian found herself trapped there in the vaudeville circuit. They were both looking for a second chance and they decided to reinvent themselves.

It was good timing too—in 1902, Annie Oakley quit the Wild West show after a series of train accidents and equipment malfunctions that had caused a lot of carnage and financial issues. Her husband was going to support them at a job with a cartridge company and she was going to act, which meant that there was suddenly a vacuum in the shooting performance circuit that Lillian could fill.

However, Lillian and Frank’s first big excursion was to Hawaii, where Queen Liliuokalani had hired them to teach marines stationed in Oahu how to fire better. Frank would later claim they fled as the island erupted into protests over annexation by the United States, but contemporary news reports note they were leaving as an outbreak of bubonic plague hit Honolulu at the end of 1899.24 It’s unclear why there’s a discrepancy here—perhaps Frank genuinely didn’t remember, or maybe he fudged the truth because the plague next spread to San Francisco and he didn’t want them to be blamed for that.

After Hawaii, the couple moved to Chicago, where they began performing on the Orpheum vaudeville circuit. They performed well together, sending out press kits with photos of them both dressed in fancy Victorian clothes; some included promotional cards that included a hole in the middle and read “Shot by Lillian F. Smith, ‘The California Girl,’ Champion Rifle Shot of the World, While Held in the Hand of Frank C. Smith.”25 By this point, she was able to “snuff out a candle flame with her rifle, shoot the ashes off the cigar in her partner’s mouth, and break small balls suspended from Frank’s hat.”26 To be clear, when they said “snuff out a candle flame” they meant that she could shoot close enough to the candle that the bullet passing by either put out the candle or the wind from the bullet passing by did—either way, she was doing it without damaging the wax, which is pretty impressive.

Though her career was doing well again, it seems that this was a period of darkness for Lillian. Her brother and then her mother Rebecca passed away in quick succession, and she wasn’t able to say goodbye to either because of her traveling. Her mother had also been living apart from her father, and it seems that this was a source of distress for Lillian. Extant letters show that she was concerned about a younger sister named Nellie who was still under her father Levi’s control. Nellie’s parentage is a matter of some debate—she was not Rebecca’s daughter, that much historians seem sure of, but beyond that it’s unclear. Bricklin suggests she might be a secret daughter of Lillian’s, fathered by her first husband Jim and born while Jim was in Europe, but there is no known birth certificate for her to confirm or deny that.27 That Levi took control of the girl’s life and tried to put her on the show circuit as he had done with Lillian before is not surprising. He billed her as a new “California Girl” to replace Lillian. Regardless of Nellie’s parentage, what is known is that Lillian never saw Levi again, and he died in 1908.

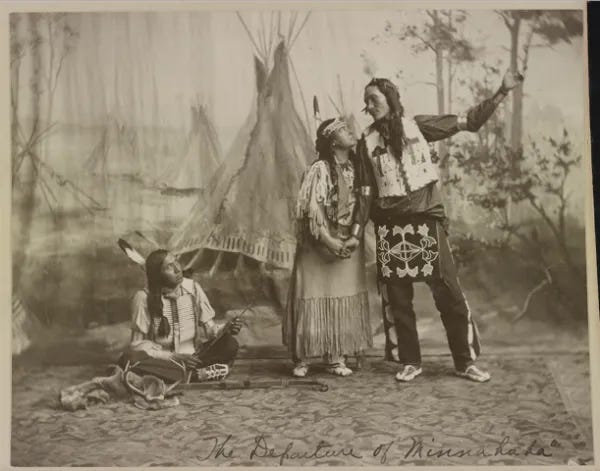

Perhaps because of this darkness, when Frederick Cummins’ Indian Congress approached Frank and Lillian to join them for the World’s Fair in Buffalo, they jumped at the opportunity to fully reinvent themselves. Lillian began going by Wenona, a half-Sioux woman to fit in with Cummins’ show, which included other famous frontier characters like Calamity Jane and Geronimo, an “embattled Apache chief.”28 The name was drawn from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, The Song of Hiawatha.

While some might suggest that Lillian adopted the Wenona stage persona as one last desperate attempt to distinguish herself from Annie Oakley, it seems more likely that Lillian discarded her identity as the California Girl to distance herself further from her father and her family and a dark past. She was perhaps trying to escape something.

Her husband Frank probably encouraged this, knowing that it was a money-maker. At the turn of the 20th century, Americans were suddenly nostalgic for the “noble race” that they had wiped out with violence and illness.29 There was something of a fad of wanting to see the last of the Indigenous Americans in their “natural state.”30 The story they cooked up was that Lillian had been born of a Sioux chief and a white woman, raised among the Sioux, and then rescued by Frank, who cast himself as “the cowboy who brought this fair Indian maiden into a culture of civilizing whites.”31 Yeah, it’s bad. By today’s norms, this is terrible. But back then it was just show business, you could lie about anything!

In addition to the money and the psychic distance, there was probably also a big practical reason to do this—performing in Victorian dress was getting increasingly dangerous, what with the capes and velvet bedecked with ribbons and feathers; Lillian was constantly at risk for catching fire from a spark in the gun or the gas lights in the theatres. Switching to a half-Sioux persona allowed her to dress in a more scaled-down outfit which was safer and probably more comfortable for the tricks she was doing.

I haven’t talked much about what Lillian looked like, but it’s relevant here. After a lifetime—30 years—spent in the sun, her skin was pretty sun-damaged and leathery. She was also short and somewhat stout, even as a child, something people were quick to point out. For most of her career, she had been compared to Annie Oakley, and though she often won on skill, Oakley always won in looks and demeanor: She was beautiful, and Lillian was rarely treated to those compliments. Since she was already dark-haired and had dark eyes, with her darkly tanned skin, it was easy for her to pass as half-Sioux. As Bricklin writes, she might have chosen this persona because “she had found a way for her sun-toughened skin and stout figure to be something beautiful and respected—even mysterious and private, since so much of her life had been public.”32

Her costume as Wenona included what we picture as stereotypical vague Native American dress: “a fully fringed, suede tunic with intricate beadwork and a fantastic feathered headdress, which she wore even while shooting moving objects while astride a galloping horse.”33 From then on, she always dressed this way on stage, and it seems like maybe she dressed this way off stage as well; she certainly pared down her outfits from the height of Victorian fashion that she’d been wearing in the 1890s.

The shakeup revitalized their careers, and soon they were invited to join Pawnee Bill’s Wild West, where Lillian added the title “Princess” to her moniker. She was so popular that several other acts on the touring and vaudeville circuit copied her, including her sister Nellie who began going by “Princess Kiowa.”34

In 1907, Lillian and Frank moved on to the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch Wild West Show in Ponca City, Oklahoma Territory. Their contract was loose, so Frank was able to accept a side-gig at Coney Island, where he met the astonishing high-diver Mamie Francis. The two fell in love and Frank divorced Lillian to marry Mamie in 1909. Lillian briefly left the 101 Ranch Wild West Show, so we can assume there were some hurt feelings here, but she returned in 1910. Perhaps surprisingly, she and Mamie managed to strike up a friendship, and she clearly taught Mamie how to do one of her hardest tricks: shooting clay balls thrown in the air while riding a galloping horse.35 For a long time, Lillian was the only woman who had mastered it, so it must be a signal of trust and friendship that she taught Mamie to do it too.

One of her last big performances was at San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915. She began to slow down her touring at that point, choosing instead to spend most of her time back at the 101 Ranch, where she lived with American West painter Emil Lenders. It’s unclear whether they were a romantic couple or just companions, but they lived together for several years. They bought 20 acres which they called Thunderbird Ranch.36 They raised chickens, took care of 48 stray dogs, and planted peach trees and blackberry vines and operated as a vineyard. With Lillian in semi-retirement was her beloved trick pony, Rabbit.

The last years of Lillian’s life are a bit sad, to be honest. Lenders left her in 1926 and she spent the last bit of her life alone except for her animals and some other orphan performers who had settled around the 101 Ranch after retiring. The vaudeville circuit was dying as film started to take over as Americans’ favorite past time. When she died of heart failure on February 3, 1930, the passing of America’s best female sharpshooter really didn’t garner much attention. After death, her reputation was further overshadowed by Annie Oakley’s, who while never a better shooter than Lillian, was much better at self-promotion and fit it better with the ideals of what an American lady should be like. Oakley acted after she retired from shooting, and even in death inspired art like the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Annie Get Your Gun. For many years, Lillian Smith was simply forgotten.

When she died, Lillian requested to be buried in her Wenona costume, and the gravemarker actually read P. Wenona until 1999 when it was replaced. It’s unclear to me if she really believed herself to be Princess Wenona, or if she just needed the mental refuge from whatever had happened that made her want to leave Lillian Smith behind. She left $100 to the Salvation Army and her property, jewelry, and animals to trusted friends. She recognized her own role in history and left any items of historical value, including “two gold-plated Winchester rifles, two gold-plated Smith and Wesson revolvers, a bulletproof vest, silver spurs, horse trappings and a life-sized portrait of Princess Wenona” to the Oklahoma Historical Society.37

That is the story of Lillian Frances Smith! If you liked this story, you will love my book, Unruly Figures: Twenty Tales of Rebels, Rulebreakers, and Revolutionaries You’ve (Probably) Never Heard Of. You can let me know your thoughts about this or any other episode on Substack, TikTok and Instagram, where my username is unrulyfigures. If you’d like to get in touch, send me an email at hello@unrulyfigurespodcast.com. If you have a moment, please give this show a five-star review on Spotify or Apple Podcasts–it does help other folks discover the show.

This podcast is researched, written, and produced by me, Valorie Castellanos Clark. If you are into supporting independent research, please share this with at least one person you know. Heck, start a group chat! Tell them they can subscribe wherever they get their podcasts, but for ad-free episodes and behind-the-scenes content, come over to unrulyfigures.substack.com.

Until next time, stay unruly.

📚 Bibliography

“$1,000 in 1884 → 2024 | Inflation Calculator.” Official Data Foundation. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index. Accessed September 22, 2024. https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1884?amount=1000.

“$500 in 1884 → 2024 | Inflation Calculator.” Official Data Foundation. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index. Accessed September 22, 2024. https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1884?amount=500.

Bricklin, Julia. America’s Best Female Sharpshooter: The Rise and Fall of Lillian Frances. University of Oklahoma Press, 2017. https://bookshop.org/a/79066/9780806156330.

———. “Lillian Smith: The On-Target ‘California Girl.’” HistoryNet, November 25, 2014. https://www.historynet.com/lillian-smith-the-on-target-california-girl/.

———. “The Faux ‘Sioux’ Sharpshooter Who Became Annie Oakley’s Rival.” Smithsonian Magazine, Mau 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/faux-sioux-sharpshooter-who-became-annie-oakleys-rival-180963164/.

Kasper, Shirl. Annie Oakley. University of Oklahoma Press, 2000.

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. The Song of Hiawatha. Ebook. Project Gutenberg, 1991. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19/19-h/19-h.htm.

Takai, Yukari. “Epidemics and Racism: Honolulu’s Bubonic Plague and the Big Fire, 1899-1900.” Active History (blog), June 12, 2020. https://activehistory.ca/blog/2020/06/12/epidemics-and-racism-honolulus-bubonic-plague-and-the-big-fire-1899-1900/.

The Illustrated London News 1887-05-21: Vol 90 Iss 2509. London: Illustrated London News, 1887. http://archive.org/details/sim_illustrated-london-news_1887-05-21_90_2509.

The Los Angeles Times. “At the Playhouses.” December 3, 1895.

Julia Bricklin, America’s Best Female Sharpshooter: The Rise and Fall of Lillian Frances (University of Oklahoma Press, 2017), https://bookshop.org/a/79066/9780806156330.

Bricklin, 17

Bricklin, 18

Bricklin, 18

Bricklin, 19

Bricklin, 22

Bricklin, 23

“$500 in 1884 → 2024 | Inflation Calculator,” accessed September 22, 2024, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1884?amount=500.

“$1,000 in 1884 → 2024 | Inflation Calculator,” accessed September 22, 2024, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1884?amount=1000.

Bricklin, 21

Bricklin, 36

Bricklin, 36

Bricklin, 37

Bricklin, 37

Shirl Kasper, Annie Oakley (University of Oklahoma Press, 2000).

Bricklin, 42

Bricklin, 44

The Illustrated London News 1887-05-21: Vol 90 Iss 2509 (London: Illustrated London News, 1887), http://archive.org/details/sim_illustrated-london-news_1887-05-21_90_2509.

The Illustrated London News, 583

Bricklin, 54

Bricklin, 59

Bricklin, 64

“At the Playhouses,” The Los Angeles Times, December 3, 1895.

Bricklin, 70

Bricklin, 73

Bricklin, 73

Bricklin, 72

Bricklin, 75

Julia Bricklin, “The Faux ‘Sioux’ Sharpshooter Who Became Annie Oakley’s Rival,” Smithsonian Magazine, Mau 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/faux-sioux-sharpshooter-who-became-annie-oakleys-rival-180963164/.

Julia Bricklin, “Lillian Smith: The On-Target ‘California Girl,’” HistoryNet, November 25, 2014, https://www.historynet.com/lillian-smith-the-on-target-california-girl/.

Bricklin, “The Faux ‘Sioux’ Sharpshooter”

Bricklin, “The On-Target ‘California Girl’”

Bricklin, “The Faux ‘Sioux’ Sharpshooter”

Bricklin, “The Faux ‘Sioux’ Sharpshooter”

Bricklin, “The On-Target ‘California Girl’”

Brickling, “The On-Target ‘California Girl’”

Brickling, “The On-Target ‘California Girl’”

#47: Lillian Frances Smith