Hello everyone,

Thank you for all your love on the launch of Künstlerroman! I’m already really enjoying connecting with all the historical fiction writers on Substack through these posts.

Last time, I talked through part one of turning an enormous pile (or, document, as it were) of research into a plotline. I covered making research into a timeline, how to layer a real person’s biography with other historical forces, identifying who some of the side characters are going to be, and more. Now that I have those timelines, we’re going to look at how to actually create a plotline out of that.

I love to use a classic three-act hero’s journey structure, especially for a novel that centers on one main character. I’m not going to get too into what the hero’s journey is,* just because a million people already have, many better than I could ever hope to. Suffice to say that it’s a classic way to look at story structure.

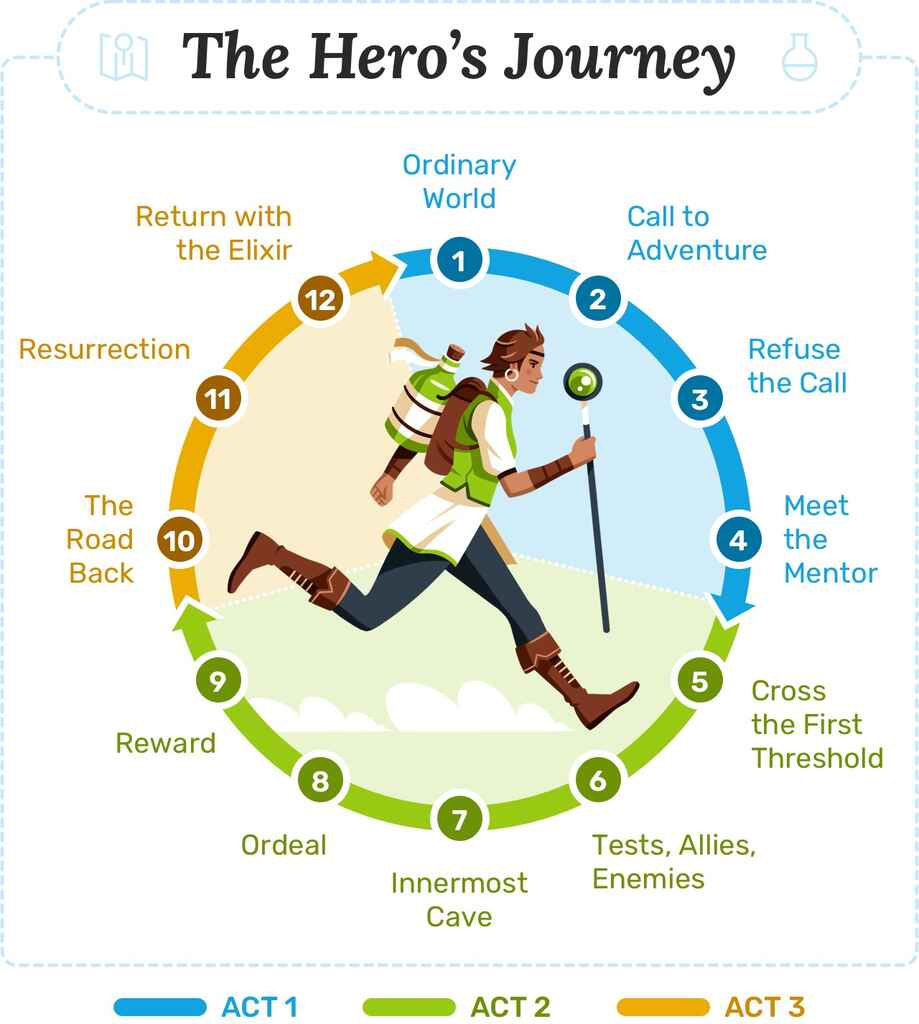

If you’re unfamiliar, the journey looks like this:

(I do particularly like this graphic because I think the color-coded acts help show how long Act Two really is compared to the other two acts. It only has 5 steps (cross the threshold through reward), but this is where most of your plot points end up.)

Basically, I use this structure to transform my MC’s life story into a plotline that has narrative tension. We have to, because the reality is that—while history contains the word story—true history often doesn’t have an easy-to-follow plot or narrative tension. It tends to wander and meander; a lifetime can take 80+ years after all. Events seem to start and then pick up again 20 years later, patterns reverse, subplots get forgotten. So, for a historical novel, I don’t start at birth and end at death (though I do exactly that in podcast episodes). Instead, I pluck the story out of someone’s life that I want to tell, fully recognizing that their life is far more complex than I could ever capture in 100,000 words.

I don’t want to sound cavalier about this because I actually think it can be the hardest step. With my first historical fiction novel, this step stalled me for months because what I think counts as the “dark night of the soul” (or “the cave” and “ordeal” above) for that novel were the deaths of two of my MC’s children. But those deaths happened several years apart, and a whole lot of story happened in between them. I couldn’t figure out a way to have her grieve two significant deaths, several years apart, and not lose all narrative tension.

My solution was to have her be in such firm denial about the first child’s death that she just behaved as if he were still alive. Talked about him, talked to him, made plans for his future… just simply did not accept that he had died until her second child died, and then she had to deal with both griefs at once. I think taking that path makes the impact of the reckoning that happens in the dark night of the soul plot point all the more powerful.

So for this new novel, I want to start with the moment my MC rightfully inherits her uncle’s title and land, but that inheritance is challenged. In reality, she was raised to be a duchess regnant and lived somewhere that women could inherit directly, but it was a changing world—salic law already existed, but she lived through a period of its tightening, when even inheritance claims could no longer be passed down through women to their sons or grandsons. I want that tension to weave into the novel.

The challenge to her inheritance sparks a war… but first it’s a court case. My debate right now is where the cross the threshold/refuse the call parts of this story happen. If I treat the war as inevitable, then the court case can be the refusal and the first shots fired in the war, so to speak, can be the crossing. (This is not the order of the graphic above, but the most fun thing about plotlines is playing with them!)

What I think is going to end up being a sticking point for me this time around is the final act—the road back, the resurrection, the elixir. My MC lived to be in her 80s, and in her final decades of life, the debate over her inheritance was resurrected. The war began anew, but it didn’t end happily for her. The hero’s journey doesn’t demand a happy ending, but writing a tragic hero’s journey isn’t something I’ve done before. The resurrection is going to become destruction; the elixir a poison.

I try to look at story structure—any structure, not just the Hero’s Journey—as pegs to hang the story on or drape it over. It doesn’t have to fit perfectly, but the structure holds the story up. With historical fiction, the key becomes figuring out how to hang real events from the pegs of a good story structure. Identifying the theme you want to play with, the meaning of the story you’re telling, is a good way to get started.

If you have any questions for me about writing historical fiction—or anything else—drop them in this AMA and I’ll get to them in September!

Our Next AMA

A couple of years ago, I did the first-ever Unruly Figures Ask Me Anything! We had a great time, and then two years elapsed before I remembered that hey—we should do another! So, as promised, I’m back with a really-occasional-let’s-not-put-a-regular-cadence-on-it

*I also don’t want to get into this because I have strong feelings about the fact that the hero’s journey was developed by Joseph Campbell as a way of saying, “look at these features that all these myths have in common!” He wasn’t writing a storytelling instructional guide. The Hero With a Thousand Faces was basically an academic thesis about myth, narratology, and how the story beats of any heroic tale are not unique. If he knew we used it to plot stories, he’d probably roll over in his grave. That said… as a structure, it works.