Niko Angell-Gargiulo on Robert de Montesquiou

Hey everyone,

Today we’ve got a bonus essay from

all about the fin-de-siecle aesthete Count Robert de Montesquiou. He was a poet and urban aesthete, but he’s mostly remembered for the wonderful literary characters he inspired. Niko discusses his importance to modern understandings of France at the turn of the 20th century and how interior decorating is at the heart of it all.If you like this, you’re going to love Niko’s podcast. Check is out here:

In Search of Robert de Montesquiou

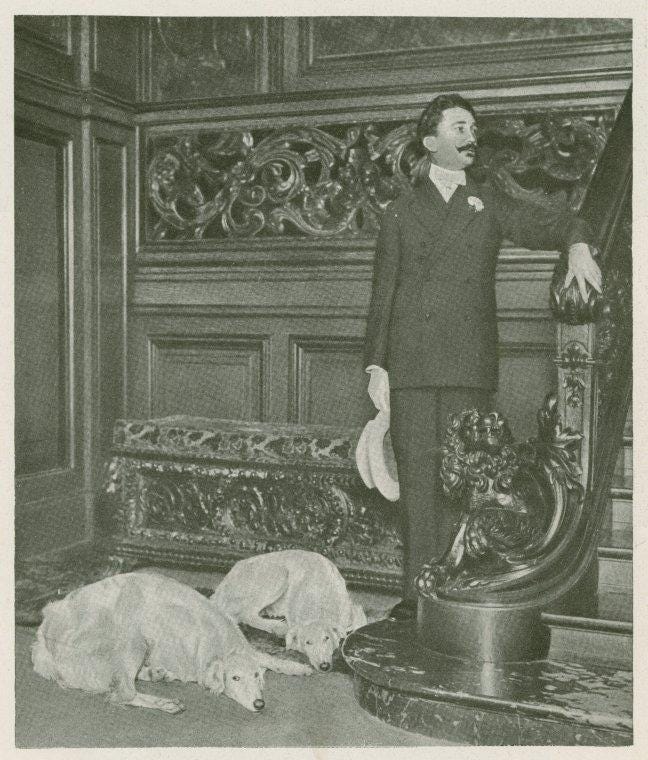

Robert de Montesquiou was a dandy, esthete, and symbolist poet of the fin de siècle, most famous for being the inspiration of Baron de Charlus in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time and the central character, Jean des Esseintes, in Joris-Karl Huysmans’ Against Nature. A painting from 1891 by James Whistler portrays Montesquiou as a tall, dignified figure, a rich fur coat draped over his arm, and in his other gloved hand, he holds a walking stick, ready to go out for the night. An aristocrat with means and money, Montesquiou dipped his fingers into many different eccentric hobbies, from theater to literature, sports to decoration. His status made him popular in high society during his lifetime, while in contemporary and popular literature, he remains mostly unknown. He cultivated friendships with novelist Marcel Proust, writer Edmond de Goncourt, painter James Whistler, actress Sarah Bernhardt, doctor Samuel Jean Pozzi, glass artist Émile Gallé, and more.

Like anyone else, there are many ways to talk about Montesquiou—his sexuality, his involvement in the visual arts, his interest in theater—but today I want to talk about his literary representations, what those characterizations got wrong, what they got right, and why interior decorating is at the heart of it all.

Released in 1884, Against Nature by Joris-Karl Huysmans was an instant, if not slightly controversial, hit. A staple of the decadence movement (an artistic and literary movement that centered on excess and artificiality), the book was praised for its vivacity by Oscar Wilde while Emile Zola decried that it dealt “a terrible blow to naturalism.”1 The story recounts the fictional eccentricities of Jean des Esseintes, the scion of an aristocratic family who shuns society and moved away from Paris to cultivate an aesthetic lifestyle filled with artifice. In one famous chapter, he paints his tortoise in gold and bedecks it with jewels before the animal succumbs to the weight. In another chapter, he hallucinates the smell of frangipane filling the room, which can only be cured by concocting new perfumes. He collected paintings and works by symbolist painters and writers such as Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, Paul Verlaine, and Stephen Mallarmé, which decorated his house. By the end of the book, the count has shunned the real world and its flaws, instead retreating to his isolated, artificial mansion.

The character of des Esseintes took inspiration from many nineteenth-century dandies and aesthetes: King Ludwig II of Bavaria, known for his reclusive and eccentric nature. Popular novelist Edmond de Goncourt published La Maison d'un artiste (The House of the Artist) four years earlier, which listed the contents of his own over-decorated house. Even Charles Baudelaire, who described his experience with psychedelics in Les Paradis Artificiels (The Artificial Paradises), played a role in the formation of des Esseintes.2 But the person who became a celebrity from the book was none other than Robert Montesquiou.

The book brought the 28-year-old count attention and scandal. Critics made the assumption that the two were the same for years. A review for Montesquiou’s own poetry in 1894 opens, “You remember des Esseintes, the ineffable hero of Against Nature…” One story recounts how a rare bookseller, not recognizing his customer as Montesquiou himself, cried out, “Why, Monsieur, those books are fit for Des Esseintes!” to the annoyance of Montesquiou.3 His general public image was flattened to caricature.

Also the scion of an elite family, Robert de Montesquiou was born on March 7, 1855, on the left bank of Paris at 60 rue Varenne.4 The Montesquious were a noble family, tracing their lineage back to the eleventh century. His paternal grandfather, Count Anatole de Montesquiou-Fézensac, won honor for the family as an aide-de-camp to Napoleon. Like many nobles under the Second Empire, the family took residence in the neighborhood of Faubourg Saint-Germain, now the seventh arrondissement in Paris. The air of the upper crust was leisurely and degenerate. “The men were more elegant than the women and the women often more cultured than the men,” Phillipe Jullian wrote in his biography of Montesquiou, Prince of Aesthetes.5 Montesquiou took after his grandparents and their grandeur style, which would be emulated by des Esseintes in Against Nature.6

But as Jullian points out, there were also a host of differences between the character and the model. Most significantly, Montesquiou was sociable; he liked to laugh and to make others laugh.7 He first made his name in the social circles of the elite Faubourg Saint-Germain crowd: women, dowagers, countesses who gave their artistic opinions in salons; sons of dukes who were horsemen and runners. These people were the idle rich and had nothing else to do besides spend their money on idle hobbies. Mingling in a crowd of well-to-do people, Montesquiou began to cultivate his own eccentric tastes and hobbies.

Still, in des Esseintes, we see the aesthetic details that characterized Montesquiou, made him unique, and attracted others to him. Huysmans and Montesquiou never met but the former had heard of the latter from the poet Stephen Mallarmé.8 Montesquiou’s decoration and eccentric collection of antiques and foreign objects showed off his dazzling style. Japanese masks, kimonos, and Asian rugs adorned the rooms. The library, taking inspiration from Whistler’s Peacock Room, was surrounded by lacquered walls with a peacock motif.9 An article in La Liberté (entitled “Les Snobs,” indicating a certain regard for the count’s personal style) recalled a visit to Montesquiou’s house and mentioned that a perfume burner was set up in each room and for a different purpose. One scent in the dining room, another in the smoking room, still another in the room where one sleeps, emitting the proper perfume for each room.10 One room was even dedicated to the moon. The midnight blue walls were accented with silver and gold and covered in a mouse-grey velvet. A roll of transparent gauze ran across the wall, studded with realistic koi fish, and gave the illusion of real water when the light hit just right.11

Of course, not just his rooms were this extravagant but so was his personality. Montesquiou was one of the first Frenchmen to wear a tuxedo in the evening. His were made of scarlet red or emerald green velvet, of course.12 Supposedly, he would wear a bouquet of violets where his tie was meant to be.13 Another journalist reported an incident where Montesquiou, unhappy that the gardenia in his outfit was odorless, doused the flower with perfume.14

This style extended to Montesquiou’s literary output. In 1892, his first book of poetry, Les Chauves-Souris, Clairs obscurs (The Bats, Light and Dark), was published in a limited run for his friends and family. Poet Stephen Mallarmé and painter James McNeill Whistler, as well as his cousin Countess Greffulhule received a copy wrapped in silk embroidered with bats.15 Sarah Bernhardt had a copy from the first public limited run of 300. Further editions included drawings from Whistler and the Japanese artist Hosui Yamamoto.16 In later volumes of his poetry, Montesquiou had famed glass-artists René Lalique print a peacock on the title page, and further collaborated with pioneering Art Nouveau artist Émile Gallé. The delivery of his poetry had to be accompanied by beautiful design.

To get a sense of how all-encompassing Montesquiou’s devotion to aesthetics and dandyism was, one only has to look to his memoir, Les Pas effaces (The Steps Erased), which recounts “mes demeures,” my mansions, my living abodes. While some might consider it egotistical to recount such trivial details, in fact, it’s the object of the house, their arrangement and their affectations, that reveal Montesquiou’s interiority, his soul. Not just their objects, but also their arrangement, as Montesquiou subscribed to the Baudelarian concept of “Correspondences.”17 The poem reads:

Nature is a temple in which living pillars

Sometimes give voice to confused words;

Man passes there through forests of symbols

Which look at him with understanding eyes.

Like prolonged echoes mingling in the distance

In a deep and tenebrous unity,

Vast as the dark of night and as the light of day,

Perfumes, sounds, and colors correspond.18

Montesquiou interpreted this poem, as it applied to his passion for interior design, to mean that truth and beauty could be found through the symbolic arrangement of objects. A perfect bedroom might be covered in purple bed sheets and curtains, scented with iris or lilac, to convey the feeling of a transitory state from consciousness to sleep. In a sense, he thought true nature could be found through artificial perfection.

If you’re reading all this and think it sounds absurd and pompous, you’re not alone. In 1919, Marcel Proust published the second of seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time, which introduced Baron Charlus, a character inspired by Montesquiou. The two had met over twenty years earlier, when Proust was a budding young writer and Montesquiou was an established figure in artistic circles. The two struck up a strange friendship: Proust listened to Montesquiou’s stories and musings for hours on end while also being sure to complement the Count’s ego at every opportunity. Bernard Berenson supposedly commented on the relationship: “A novelist’s best inspiration is not that which comes directly and immediately from whatever happens to him, but is that which comes from narrated facts passing through the screen of another voice… This was the sort of inspiration Proust derived from his mentor, Montesquiou.”19 The result was Baron Charlus, a narcissistic gay man with an affected and a neurotic manner whose sexual deviancy leads him to spiral out.

On the surface, Proust paints Montesquiou, as Charlus, in a negative light as petty, superficial, and egotistical. These negative aspects of his personality are heavily associated with his strange aesthetic mannerism. But this very aesthetic taste and appreciation attracted Proust to Montesquiou in the first place. Elsewhere, Proust bestowed on Montesquiou the title “Professor of Beauty,” which speaks to his taste and is reflected in his friendship with some of the most famous artists and novelists. Montesquiou sought out composer Claude Debussy, corresponded with sculptor Auguste Rodin, and became friends with many more prominent artists, writers, and actors. In an age of seeming superficiality and pettiness, Montesquiou was one who knew the power of aesthetics.

Montesquiou’s style today might be called ‘camp,’ rather than ‘snobbish’—overly exaggerated and completely artificial (maybe think of a nineteenth-century John Waters). But it was also in the style of the late nineteenth century. Around this time, Montesquiou’s good friend Sarah Bernhardt was posing for portraits in her coffin and wearing taxidermy bats on her head. Beneath Montesquiou’s strange style lay a great desire to bring together true art and beauty into every aspect of his life, through common objects and room arrangements. In this sense, Montesquiou had an artistic and poetic flair that he used to define every aspect of his life—a flair we may consider when stylizing our own houses.

Bibliography:

Baldick, Robert. Introduction to Against Nature, by J.-K. Huysmans, 5–14. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1959.

Baudelaire, Charles. “Correspondences.” In Fleurs Du Mal, edited by Marthiel Mathews and Jackson Mathews, 12. New York, NY: New Directions, 1989. https://fleursdumal.org/poem/103.

Brisson, Adolphe. “Les Snobs.” La Liberté, February 25, 1901. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3486682j.

Jullian, Philippe. Prince of aesthetes: Count Robert de Montesquiou, 1855-1921. New York: Viking Press, 1968. https://archive.org/details/princeofaesthete0000jull/mode/2up.

Montesquiou, Robert de. Les Pas effacés : mémoires. 3 vols. Paris : Emile-Paul Frères, 1923.

Montesquiou-Fezensac, Comte Robert de, and Prince Edmond de Polignac. “Papiers de Robert de Montesquiou.” Paris, 1893. Département des Manuscrits. NAF 15115NAF 15114-15115. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10085640s.

Silverman, Willa Z. “Unpacking His Library: Robert de Montesquiou and the Esthetics of the Book in ‘Fin-de-Siècle’ France.” Nineteenth-Century French Studies 32, no. 3/4 (Spring Summer 2004): 316–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23538017.

White, Edmund. Marcel Proust. New York: Viking Press, 1998. iBooks.

Robert Baldick. Introduction to Against Nature, by J.-K. Huysmans, 5–14. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1959.

Baldick, 7.

Baldick, 8.

Philippe Jullian. Prince of aesthetes: Count Robert de Montesquiou, 1855-1921. New York: Viking Press, 1968. https://archive.org/details/princeofaesthete0000jull/mode/2up.

Jullian, 16.

Jullian, 23.

Jullian, 51.

Jullian, 49, 51.

Willa Z. Silverman. “Unpacking His Library: Robert de Montesquiou and the Esthetics of the Book in ‘Fin-de-Siècle’ France.” Nineteenth-Century French Studies 32, no. 3/4 (Spring Summer 2004): 316–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23538017.

Adolphe Brisson, “Les Snobs,” La Liberté, February 25, 1901, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3486682j.

Jullian, 45.

Jullian, 82.

Jullian, 50.

Comte Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac and Prince Edmond de Polignac, “Papiers de Robert de Montesquiou” (Paris, 1893), Département des Manuscrits. NAF 15115NAF 15114-15115., Bibliothèque Nationale de France, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10085640s.

Jullian, 127.

Silverman, 330.

Montesquiou 3: 62-63.

Charles Baudelaire, “Correspondences,” in Fleurs Du Mal, ed. Marthiel Mathews and Jackson Mathews (New York, NY: New Directions, 1989), 12, https://fleursdumal.org/poem/103.

Jullian, 157.