Thanks for checking out Unruly Figures! I’m able to keep these transcripts free because of the amazing people who help support this work. Want to support independent and in-depth research? Subscribe now for just $6/month or $60/year!

Hello, hello friends! Today I’ve got the transcript and bibliography for Unruly Figures episode 14, Stormé DeLarverie. At the beginning of each paragraph is a time code for where you can find that in the episode. I also do endnotes throughout, in case you want to follow up with a resource for more reading!

🎙 Transcript

Here’s the episode:

0:06 Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m going to be covering one of the United States’ great queer icons: Stormé DeLarverie. [Pronounced: Storm De-Lah-vee-yay.]

0:18 DeLarverie is remembered as the woman who threw the first punch at Stonewall. She was also a jazz singer, a drag king, a cabaret performer, and she eventually caught the eye of legendary photographer Diane Arbus. Her story is a fun one, and I kind of can’t believe that I had never heard of DeLarverie until I started researching Pride for an article in May. Oh, but a quick warning, this story does touch on a little homophobia and violence. It’s when I talk about Stonewall, so if that makes you uncomfortable just skip ahead a few seconds.

0:46 Before we get into her story: For a full transcript of today’s episode, head over to Unruly Figures dot Substack dot com. That’s U-N-R-U-L-Y-F-I-G-U-R-E-S dot S-U-B-S-T-A-C-K dot com. In addition to the full transcript, you can also get ad-free episodes, a bibliography of my research, photos of everyone I’m covering, discussion threads, and so much more. So check it out!

1:08 All right, let’s hop back in time.

1:11 Stormé DeLarverie was born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1920. She apparently never knew her exact date of birth, but she always celebrated her birthday on December 24th. Her father was white and her mother was Black, which was a big deal in Louisiana where interracial relationships were frowned upon and interracial marriage illegal. Her mother was actually a servant in her father’s household, which is troubling a little bit right off the bat, due to power dynamics and consent issues. However, we know her father acknowledged her and took care of her, and at least one article mentioned that the couple eventually married and moved to California, though I only saw that in one place. According to another documentary, it was her grandfather who did the bulk of the parenting though.1

1:51 According to the website them, Stormé was never issued a birth certificate because of her parents’ different races.2 This is supposed to explain why she didn’t know her exact birthday. Of course, we’ve talked a little in the past about people’s own mythmaking, and how sometimes stories or jokes or incomplete explanations end up passing into the historical record as fact. And I’m fairly sure this idea that Stormé wasn’t issued a birth certificate because her parents were of different races is, at best, incomplete.

2:16 First of all, birth certificates even in 1920 weren’t as common and well-regulated as they are today. In the book The Birth Certificate: An American History, author Susan J. Pearson talks about early twentieth-century campaigns for mandatory birth certificates, pushed forward in large part by Progressives who needed birth certificates to exist across the board so they could prove children’s ages so that they could then enact research and policies around infant mortality, child labor laws, education reform, et cetera. As late as 1917, organizers of “baby weeks” in states like Louisiana aggressively pushed registration as part of child welfare.3 During one of these baby weeks in Louisiana, a parade that was part of the festivities had a banner in it that said, quote, “Louisiana babies’ first plea: Doctor I want a record for me.”4

3:03 Second of all, in 1920 Jim Crow was still the law of the land, and governments were very interested in tracking people’s race. Yes, interracial marriage was illegal, but the only way governments could prove that a marriage was interracial is if both members had birth certificates documenting their race. And Pearson’s book gets into some really interesting stories around people who presented as white but were categorized as Black on their birth certificates, and how that led to marriages being annulled. So, if Stormé’s parents were married, the marriage might have been annulled if discovered when Stormé was born, but that wouldn’t have been a good enough reason for other people involved to not document Stormé’s birth and especially not document that one of her parents was Black.

3:43 On the one hand, it’s possible she wasn’t issued a birth certificate because someone just forgot to do it. I have doubts about the reason people claim why she wasn’t issued a birth certificate, but not having one at that time was common enough. On the one hand, it seems unlikely to me that this biracial child born in a major city in 1920 wouldn’t have a birth certificate at all specifically because the government would have wanted to track her and count her as part of the Black population and use this certificate as proof to deny her equitable housing and education for her whole life. It’s not great, don’t get me wrong, it’s a gross reason, but that’s the reality that we’re working within the South in 1920.

4:18 My best guess is that DeLarvier probably did have a birth certificate and it was probably just misplaced at some point. The other option is that perhaps her mother decided not to give birth in a hospital because of the fears around the illegality of her relationship with Stormé's father, but I mean, this is wild speculation at this point, so. Anyway, I know that was a long tangent, I just wanted to kind of point it out because I saw that repeated in a lot of places and it just kind of… I don’t know, twigged my historian spidey-senses. I just wasn’t sure about it. Anyway—back to the story!

4:49 As a child, DeLarvier was bullied and even beaten by the other local kids for being biracial.5 One incident left her with a permanent leg brace; another was intense scarring—another left her with intense scarring from being hung on a fence.6 Eventually, her father paid to send her to a private school further north to protect her. Nevertheless, her grandfather once told her that, quote, “If I didn’t stop running, I’d be running for the rest of my life. And when I was 15, I stopped running, and I haven’t run a day since.”7

5:15 End quote.

6:16 We don’t know when exactly, but she joined the Ringling Brothers circus as a teen. She traveled with the circus and rode jumping horses side-saddle, which sounds very difficult to me.8 In 1938, at the age of 18, Stormé moved to Chicago, citing concerns that she’d be killed for being both biracial and a lesbian in the South.9 There, she began singing with jazz bands in clubs across the city. There’s also some indication that she worked as a bodyguard to some mobsters in Chicago, creating a link that would continue for a while.10

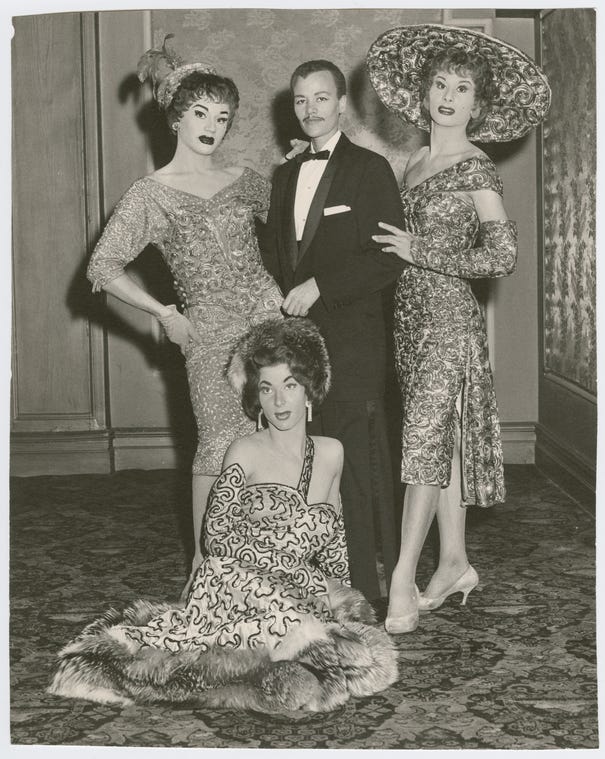

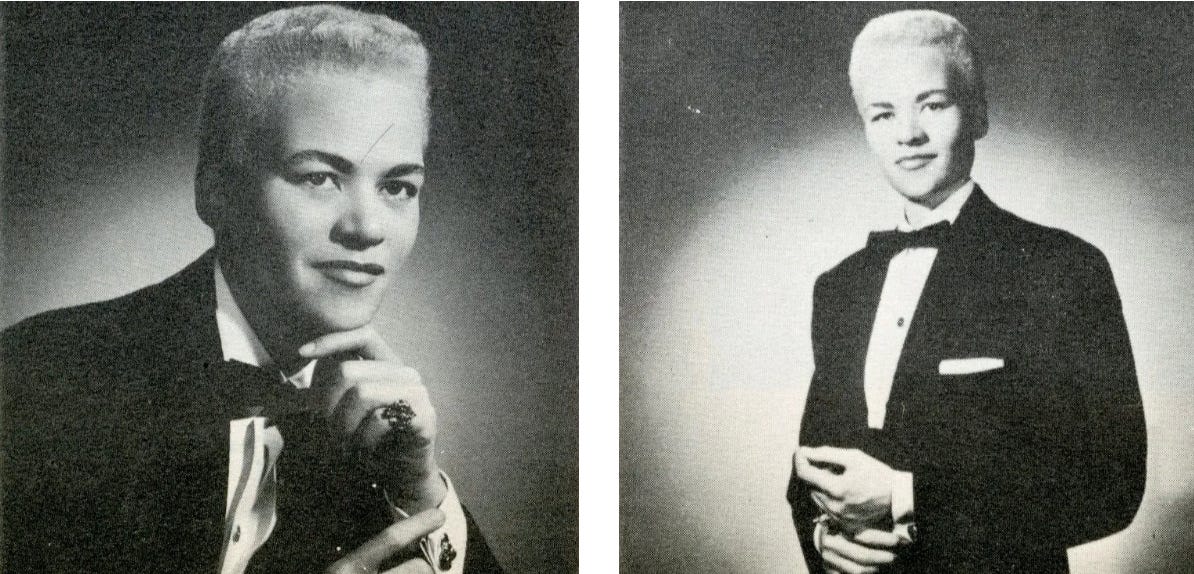

5:42 In the early 1950s, she visited Miami and met Danny Brown and Doc Brenner of the venue Danny’s Jewel Box. They wanted to put on a show and asked for her—and asked her to help. She agreed to stay and help for 6 months but ended up staying for nearly 14 years. She became the emcee of the Jewel Box Revue, a touring drag cabaret that traveled all over the US in the 1950s and 1960s. They were known for—uhh, almost a game that they would play with audiences. They said the troupe was 25 men and a woman, and audiences would kind of spend the show watching the 25 drag queens on stage, trying to guess which one was the woman. At the end, while singing “A Surprise With A Song” the impeccably suited emcee would reveal her true identity as Stormé, delighting audiences.11 Back then she was called a male impersonator; today we’d call her a drag king. It was more rare to be a drag king than a drag queen, even then, and so even though audiences were used to drag queens this reveal was always surprising to folks.

6:39 Before she got started, friends of hers asked if she was sure she should do this, if performing in drag wouldn’t ruin her reputation. In the [ITL] documentary, she remembered them asking, quote, “Didn’t I already have enough problems, being Black?” Her response is killer. She said, “Well I didn’t have any problem with it, everybody else did.”12 End quote.

6:58 Notably, the Jewel Box Revue was the first racially integrated show of its kind.13 Audiences were very diverse to reflect the show: Black and white, queer and straight patrons all intermingled at Jewel Box Revue shows, including families. The show was family-friendly and supposedly very fun. She performed with the show from 1955 to 1969. According to the New York Public Library Archives, “The Revue was a favorite act on the black [sic] theater circuit and regularly played the Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York.” 14

7:25 In a documentary, Stormé: The Lady of the Jewel Box, DeLarverie said of this role, quote, “It was very easy. All I had to do was just be me and let people use their imaginations. It never changed me. I was still a woman.”15 Even when not on stage, DeLarverie tended to dress in pretty masculine attire, especially in tight pants and big loose jackets.

7:42 By her own account though, DeLarverie tried to do, quote, “the right thing, wear men’s clothes on stage and wear women’s clothes on the street. I got picked up twice for being a drag queen!”16

7:51 Of course, people across history have dressed in clothes not traditionally made for their bodies. However, DeLarverie’s combined fashion sense and role as the famous performer of the Jewel Box Revue made her a groundbreaking icon of fashion androgyny. According to GQ her, quote, “publicity photographs show a dandyish approach to zoot suits and black tie. Gender-fluid dressing has become a major force in fashion over the past few seasons, but DeLarverie’s approach to style is an early, striking instance of it.”17 End quote.

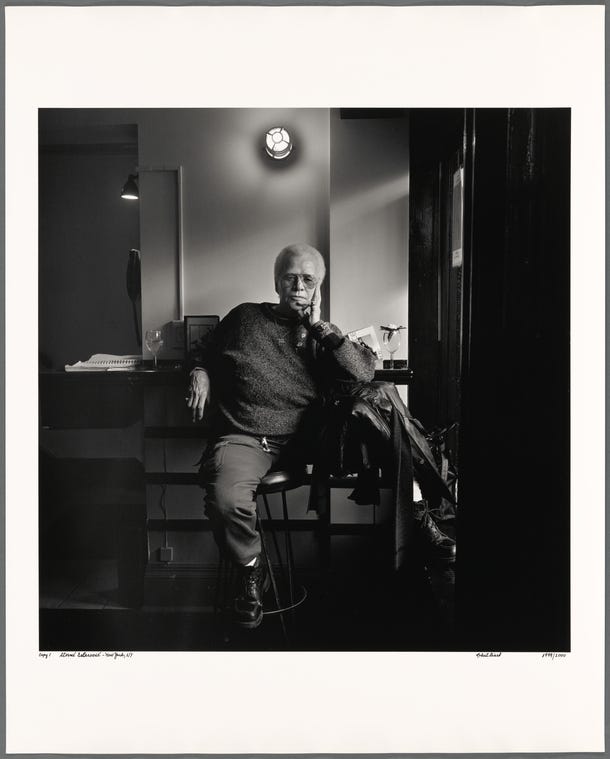

8:19 The Jewel Box Revue made DeLarverie so famous she began hanging around with really famous people like Billie Holiday. She also caught the attention of famous fine art portrait photographer Diane Arbus around 1961. She sat for a portrait on a bench in a park, wearing a lovely tailored suit with black boots. In one hand she holds a cigarette, and she looks into the camera with something like bemusement. Many of Arbus’s photos capture a certain grittiness, but this one is all elegance. Her daughter, Amy Arbus, reviewed the photo in 2016, and said that DeLarverie, quote, “looks every bit as intrigued about the photographer, as the other way around. It is a kind, gentle, completely unadorned investigation of an open, honest soul who seems a bit bemused.”18 End quote. I’ve included the photo–and several others!–in the transcript on Substack.

9:15 Sometime before the summer of 1969, then 48 years old, DeLarverie left the Jewel Box Revue to move to New York. She quickly befriended the queer community and was at the Stonewall Inn on June 28th, the night that the police raided.

9:29 A little background on Stonewall Inn is in order, I think. It sat at 53 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village. Like many of the gay bars and clubs of New York City, it was owned by the mafia, the Genovese Crime family to be exact.19 They had registered it as a private club, meaning guests had to be “members” and sign, like, a piece of paper as they came in. Uhm, and also supposedly bring their own alcohol, though often the mafia provided bootlegged liquor that could be purchased. The family would bribe the police to ignore the activities at the establishments they owned across the city.

10:01 Now, before you think the Mafia was doing this as some sort of like… allyship and crusade against homophobia, they were not. Because the bar was not subject to oversight by local government, it didn’t have running water behind the bar, the toilets didn’t really work, there wasn’t a fire exit.20 You know, it was just sort of a nightmare of regulation violations. Also, the mafia tended to use that sign-in sheet to blackmail wealthier or famous patrons who were trying to keep their sexuality a secret. But, for the LGBT community, having a space where they could congregate away from police interference was a half-step up from the harassment they had to endure in public spaces in the 1960s.

10:38 And so, in short order, Stonewall Inn became a Greenwich institution. According to History.com, quote,

It was large and relatively cheap to enter. It welcomed drag queens, who received a bitter reception at other gay bars and clubs. It was a nightly home for many runaways and homeless gay youths, who panhandled or shoplifted to afford the entry fee. And it was one of the few—if not the only—gay bar left that allowed dancing.21

11:00 End quote.

11:01 At the time, for context, dancing with someone of the same sex was illegal in New York, and in many places. But Stonewall had two dance floors and allowed dancing, which was a really big draw for people.

11:14 However, raids were “a fact of life,” I guess because even the corrupt cops had to at least look like they were trying?22 The ones accepting bribes would usually tip off the mafia in advance so that they could be sure to hide any illegal activities and present sort of an acceptable face for the cops arriving. It’s worth noting, in fact, that the Inn had just been raided a few days before, with advanced warning that time.

11:36 But in the early hours of June 28, 1968, the police came again. This time, there had been no warning. They found bootlegged alcohol and people dressed in clothes that violated New York’s gender-appropriate clothing statute. The police arrested a dozen people and subjected the people they thought were crossing-dressing to an invasive inspection of their genitals to see if their clothing matched their sex. The patrons, fed up by the constant harassment from police, stuck around instead of dispersing that night, watching the event unfold.

12:04 It is slightly debated, but many say that DeLarverie was the, quote, “cross-dressing lesbian,” end quote, who threw the first punch.23 Apparently, a police officer, mistaking her for a man in her masculine attire, told her to, quote, “Move along.”24 End quote.

12:18 Another version of the story goes that DeLarverie was being roughly led out of the Inn by a police officer, already wearing handcuffs. She was fighting back, almost escaping on several occasions. She took on four officers at once as they tried to manhandle her into a waiting police wagon. At some point, an officer hit her over the head with a baton, and even with blood running down her face she continued to fight back. At this point, she looked out at the crowd that had gathered on the sidewalk and screamed at them, “Why don’t you do something?”25 When an officer picked her up and all but threw her into the wagon, the crowd went, quote, “berserk” and that was the beginning of the several days of fighting.26

12:52 (As a side note, some people say that the fighting around Stonewall lasted for three days, some people say five, yet others say six days. How long you say the unrest went on sort of depends on what you’re terming as “unrest.” You know, so, if you go on and do more reading on your own, you’ll see all of those lengths of time mentioned.)

13:12 This is what happened in the days that followed, according to the Rainbow Times. Quote:

hundreds of queer and trans people fought the police with their fists and thrown objects. They pulled up a parking meter and used it to barricade police inside the bar, started fires, and damaged cars and property as crowds of 500 to 1,000 people rioted in the surrounding streets.27

13:30 End quote.

13:32 This was not the first protest for the rights of LGBTQ+ people in the United States, that’s definitely worth noting. But several things made it different: The scope, with hundreds of people participating for days on end, for one. The media presence was another: Coverage of Stonewall began that same morning.28 It didn’t go unnoticed. And importantly, I think, Stonewall also came at the tail end of a decade of protesting. Almost every summer in the 1960s, major American cities experienced some unrest, whether it was the Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles in 1965, the Detroit riots in 1967, and the unrest across the US after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968.29 I mean, by 1969, people had learned that peaceful protest wasn’t as effective as civil disobedience, and so they might have seen Stonewall for what it was almost as soon as it started: A flashpoint, the beginning of a major shift.

14:26 DeLarverie’s presence at Stonewall, and her reputation for throwing the first punch, set her on the path to becoming an LGBTQ icon. It’s worth noting that she herself pushed back against calling Stonewall a riot. She said, quote, “It was a rebellion, it was an uprising, it was a civil rights disobedience – it wasn't no damn riot.”30 She was known to say this on several occasions.

14:46 She expanded on this in Charles Kaiser’s 1997 book, The Gay Metropolis. There, she said:

“Stonewall was just the flip side of the black revolt when Rosa Parks took a stand. Finally, the kids down there took a stand. But it was peaceful. I mean, they said it was a riot; it was more like a civil disobedience. Noses got broken, there were bruises and banged-up knuckles and things like that, but no one was seriously injured. The police got the shock of their lives when those queens came out of that bar and pulled off their wigs and went after them. I knew sooner or later people were going to get the same attitude that I had. They had just pushed once too often.”31

15:19 End quote.

15:20 After Stonewall, DeLarverie became a member of the Stonewall Veteran’s Association, where she held various roles as the Chief of Security, Ambassador, and for a couple of years, Vice President. She became a regular at the Pride parade starting in 1970, though I’m not sure if she had anything to do with planning it. However, she often lead the parade in, quote, “the historic 1969 Cadillac convertible ‘Stonewall Car,’ which she called ‘Storme’s baby.’”32

15:43 In New York, DeLarverie lived at the famous Hotel Chelsea, where she, quote, "thrived on the atmosphere created by the many writers, musicians, artists, and actors."33 If you’ve heard the name Hotel Chelsea, by the way, it’s probably because poet Allen Ginsburg lived there, or because Arthur C. Clarke wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey there, or because it’s where Nancy of Sid and Nancy was found murdered. Stormé would live there for decades, until she was moved into a nursing home in her eighties.

16:08 Shortly after Stonewall, maybe as early as late-1969, DeLarverie’s long-time girlfriend Diana passed away. Unfortunately, all the historical record seems to have preserved about Diana was that she was a dancer and that she and DeLarverie had been together for 25 years. DeLarverie also apparently carried a photo of Diana in her wallet for the rest of her life and never really dated anybody else. It seems like they probably got together as early as 1944 when DeLarverie was 24 years old and still living in Chicago. I wish that we knew more about her, but I couldn’t find much of anything, not even a last name.

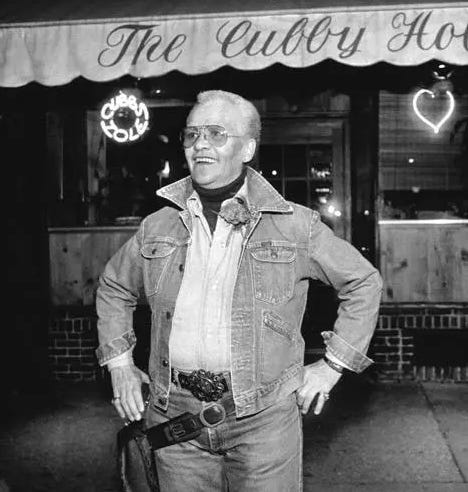

16:40 After the loss of Diana, DeLarverie left entertainment entirely. She began working as a bodyguard for rich families during the day and working as a bouncer at night. She started at Elaine Romagnoli's famous Cubby Hole and stayed there through its acquisition and change-over to Henrietta Hudson. (And I’m very sorry if I pronounced Elaine’s last name incorrectly!) She remained on staff until 2005 when she was eighty-five years old. She took this role very seriously, as it gave her a chance to watch over the young LGBT community in New York.

17:10 DeLarverie was also known for meting out vigilante justice at night. She carried a straight-edge razor in her sock and had a gun permit, so she would, quote, “roam the West Village”34 armed and keeping an eye out for what she called “ugliness: any form of intolerance, bullying or abuse of her ‘baby girls.’”35 She was seen as a guardian of all queer people, but especially lesbians in the city. Her longtime friend Lisa Cannistraci told The New York Times: “She literally walked the streets of downtown Manhattan like a gay superhero. She was not to be messed with by any stretch of the imagination.”36

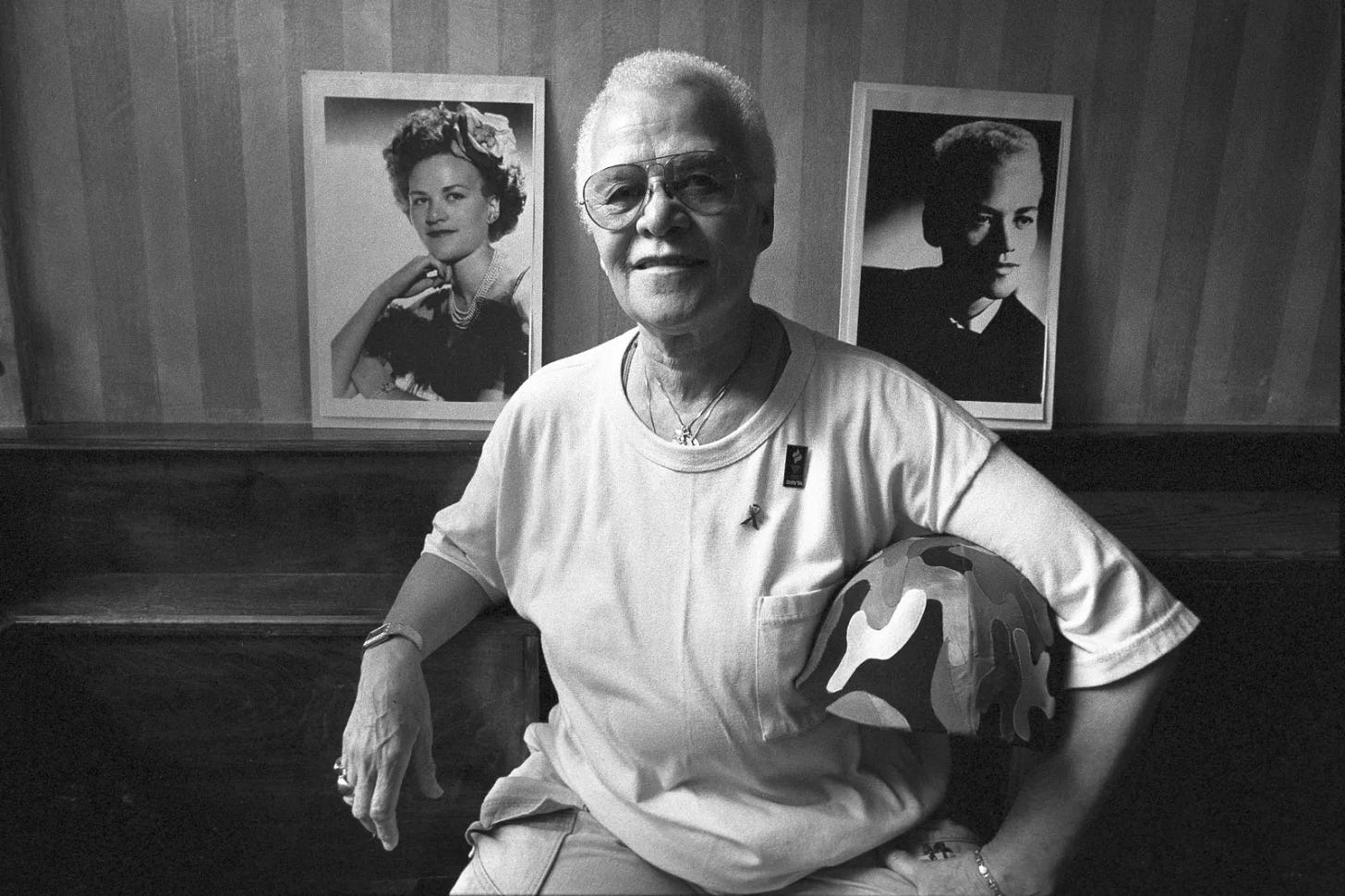

17:42 I think this risks painting a really aggressive picture, so just quickly I want to quote an obituary of Delarverie, printed in the Washington Post. The author, Jonathan Capehart, wrote, quote, “To see DeLarverie stride the streets of the Village, as I did in the 1990s, was to see what you thought was a tough dude confidently making his way through the world. To talk to her was to discover a gentle spirit steeled by life experiences.”37 End quote.

18:06 In addition to all this, DeLarverie would also work with women and children who had survived domestic violence. She organized and performed in benefits for them. When asked why she did this, she replied, "Somebody has to care. People say, 'Why do you still do that?' I said, 'It's very simple. If people didn't care about me when I was growing up, with my mother being Black, raised in the South, I wouldn't be here.'"38

18:26 Though she remained very active until she was 85-years-old, sometime after this DeLarverie began suffering from dementia and the compounding effects of old age. According to the New York Times, in 2009 a judge appointed the Jewish Association for Services for the Aged as her legal guardian, though I’m not completely clear on why. In March of 2010, she was hospitalized after she was found disoriented and dehydrated at the Chelsea Hotel; the next month she moved full-time into a nursing home in Brooklyn.39

18:53 As we saw in part two of Rosa Parks episode and in the Manuela Sáenz episode, the community her advocacy had benefited did not rise to the occasion to help DeLarverie when she needed them. Lisa Cannistraci, the long-time friend of DeLarverie and owner of the lesbian bar Henrietta Hudson, where DeLarvier had worked, expressed disappointment about this really succinctly. Quote, “The young gays and lesbians today have never heard of her, and most of our activists are young. They’re in their 20s and early 30s. The community that’s familiar with her is dwindling.”40 She added, quote, “I feel like the gay community could have really rallied, but they didn’t.”41 End quote.

19:28 In a 2001 documentary short called “A Stormé Life,” DeLarverie said, “I’m a human being that survived. I helped other people survive.” I think that’s kind of a beautiful summation of her life.

19:38 On May 24, 2014, Stormé DeLarverie passed away from a heart attack. She was 93 years old. A funeral was held a few days later at the Greenwich Village Funeral Home.

19:49 In 2019, DeLarverie was one of the fifty inaugural “heroes” inducted to the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor inside the Stonewall National Monument. It is the first US national monument dedicated to LGBTQ rights and history.

20:02 Well, that’s the story of Stormé DeLarverie! I hope you enjoyed this episode of Unruly Figures. If you follow me on Twitter or Substack, you know this episode is a little late after I had to take a trip without my microphone for a family emergency! So thank you all for your patience regarding that, I really appreciate it. And if you aren’t following along on Twitter or Substack yet, why not? We have a good time. Our handle is @UnrulyFigures. Come hang out!

📚Bibliography

Books

Pearson, Susan. The Birth Certificate. [Edition unavailable]. 2021. Reprint, The University of North Carolina Press, 2021. https://www.perlego.com/book/2388498/the-birth-certificate-pdf.

Videos

Itlmedia, director. A Stormé Life. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=XgCVNEiOwLs&ab_channel=itlmedia. Accessed 16 June 2022.

Websites

Capehart, Jonathan. “Mourning Stormé Delarverie, a Mother of the Stonewall Riots.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 2 Dec. 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-partisan/wp/2014/06/03/mourning-storme-delarverie-a-mother-of-the-stonewall-riots/.

Eskenazi, Jason. “Diane Arbus: 9 Photographers Discuss the Legend's Early Days.” Time, Time, 18 Nov. 2016, https://time.com/4429334/diane-arbus-met/.

Fernandez, Manny. “A Stonewall Veteran, 89, Misses the Parade.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 28 June 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/28/nyregion/28storme.html.

Frederick, Candice. “LGBT Icon Storme Delarverie's Personal Collection Comes to the Schomburg.” The New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, 23 June 2017, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2017/06/23/lgbt-icon-storme.

Goodman, Elyssa. “A Drag King's Journey from Cabaret Legend to Iconic Activist.” Them., Condé Nast, 29 Mar. 2018, https://www.them.us/story/drag-king-cabaret-legend-activist-storme-delarverie.

History.com Editors. “Stonewall Riots.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 31 May 2017, https://www.history.com/topics/gay-rights/the-stonewall-riots.

Matthews, Dylan. “How Today's Protests Compare to 1968, Explained by a Historian.” Vox, Vox, 2 June 2020, https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/6/2/21277253/george-floyd-protest-1960s-civil-rights.

Painter, Chad. “How the New York Media Covered the Stonewall Riots.” The Conversation, 31 July 2020, https://theconversation.com/how-the-new-york-media-covered-the-stonewall-riots-117954.

Power, Ben. “In a Stonewall State of Mind: Stormé Delarverie's Missing Recognition.” The Rainbow Times | New England's Largest LGBTQ Newspaper | Boston, 21 June 2019, http://www.therainbowtimesmass.com/in-a-stonewall-state-of-mind/.

“Stormé Delarverie.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 31 May 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storm%C3%A9_DeLarverie.

“Stormé Delarverie: Life After Stonewall.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 31 May 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storm%C3%A9_DeLarverie#Life_after_Stonewall.

Tashjian, Rachel. “A Brief History of Stormé Delarverie, Stonewall's Suiting Icon.” GQ, Condé Nast, 27 June 2019, https://www.gq.com/story/storme-delarverie-suiting.

Yardley, William. “Storme Delarverie, Early Leader in the Gay Rights Movement, Dies at 93.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 May 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/30/nyregion/storme-delarverie-early-leader-in-the-gay-rights-movement-dies-at-93.html?_r=0.

Itlmedia, director. A Stormé Life. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=XgCVNEiOwLs&ab_channel=itlmedia. Accessed 16 June 2022.

Goodman, Elyssa. “A Drag King's Journey from Cabaret Legend to Iconic Activist.” Them., Condé Nast, 29 Mar. 2018, https://www.them.us/story/drag-king-cabaret-legend-activist-storme-delarverie.

Pearson, Susan. The Birth Certificate. [Edition unavailable]. 2021. Reprint, The University of North Carolina Press, 2021. https://www.perlego.com/book/2388498/the-birth-certificate-pdf.

Pearson, chapter 3.

Goodman

Goodman

Itlmedia

Goodman

Goodman

Tashjian, Rachel. “A Brief History of Stormé Delarverie, Stonewall's Suiting Icon.” GQ, Condé Nast, 27 June 2019, https://www.gq.com/story/storme-delarverie-suiting.

Goodman

Itlmedia

Frederick, Candice. “LGBT Icon Storme Delarverie's Personal Collection Comes to the Schomburg.” The New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, 23 June 2017, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2017/06/23/lgbt-icon-storme.

Frederick

Goodman

Itlmedia

Tashjian

Eskenazi, Jason. “Diane Arbus: 9 Photographers Discuss the Legend's Early Days.” Time, Time, 18 Nov. 2016, https://time.com/4429334/diane-arbus-met/.

History.com Editors. “Stonewall Riots.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 31 May 2017, https://www.history.com/topics/gay-rights/the-stonewall-riots.

History.com Editors.

History.com Editors.

History.com Editors.

Goodman

Goodman

“Stormé Delarverie.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 31 May 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storm%C3%A9_DeLarverie.

Wikipedia

Power, Ben. “In a Stonewall State of Mind: Stormé Delarverie's Missing Recognition.” The Rainbow Times | New England's Largest LGBTQ Newspaper | Boston, 21 June 2019, http://www.therainbowtimesmass.com/in-a-stonewall-state-of-mind/.

Painter, Chad. “How the New York Media Covered the Stonewall Riots.” The Conversation, 31 July 2020, https://theconversation.com/how-the-new-york-media-covered-the-stonewall-riots-117954.

Matthews, Dylan. “How Today's Protests Compare to 1968, Explained by a Historian.” Vox, Vox, 2 June 2020, https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/6/2/21277253/george-floyd-protest-1960s-civil-rights.

Wikipedia

Capehart, Jonathan. “Mourning Stormé Delarverie, a Mother of the Stonewall Riots.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 2 Dec. 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/post-partisan/wp/2014/06/03/mourning-storme-delarverie-a-mother-of-the-stonewall-riots/.

Frederick

Wikipedia

Goodman

Yardley, William. “Storme Delarverie, Early Leader in the Gay Rights Movement, Dies at 93.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 May 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/30/nyregion/storme-delarverie-early-leader-in-the-gay-rights-movement-dies-at-93.html?_r=0.

Yardley

Capehart

“Stormé Delarverie: Life After Stonewall.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 31 May 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storm%C3%A9_DeLarverie#Life_after_Stonewall.

Fernandez, Manny. “A Stonewall Veteran, 89, Misses the Parade.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 28 June 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/28/nyregion/28storme.html.

Fernandez

Fernandez