Shammurammat: Transcript, Bibliography, and Photos

Thanks for checking out Unruly Figures! I’m able to keep these transcripts, bibliographies, and more free because of the amazing people who help support this work. Want to support independent and in-depth research? Subscribe now!

Today I’ve got the transcript and bibliography for Unruly Figures episode 12, Shammurammat. At the beginning of each paragraph is a time code for where you can find that in the episode. I also do endnotes throughout, in case you want to follow up with a resource for more reading!

🎙️ Transcript

Here’s the episode:

You can also listen to Unruly Figures on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and wherever you get your podcasts.

0:05 Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m going to be covering a woman whose very existence has a big question mark next to it.

0:18 Shammurammat, sometimes referred to as Semiramis, is said to be a queen who ruled over the ancient Neo-Assyrian empire around 811 BCE. Her reign, even her very existence, is shrouded somewhat in mystery and legend, but today we’re going to explore the tale surrounding her.

0:34 A quick note: For a full transcript of today’s episode, head over to Unruly Figures dot Substack dot com. That’s U-N-R-U-L-Y-F-I-G-U-R-E-S dot S-U-B-S-T-A-C-K dot com. In addition to the full transcript, you can also get ad-free episodes, a bibliography of my research, photos of everyone I’m covering, discussion threads, and so much more. So check it out!

0:58 All right, let’s hop back in time.

1:00 I think the best place to start is the legend of Semiramis. The ancient Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus, wrote about her in his Library of History, volume 2. He spent three chapters on her, so I’m not going to quote it all here, but the broad strokes should do.

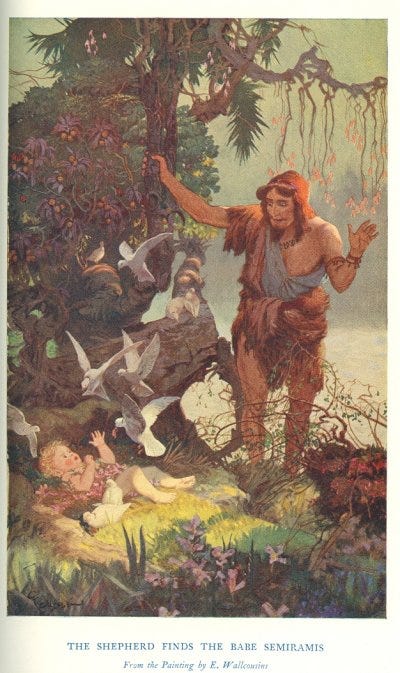

1:15 According to Diodorus, Semiramis was born to a mortal Assyrian man and a beautiful Assyrian goddess, Derceto. But Derceto had been tricked into this union, a victim of Aphrodite’s jealousy over her beauty. When Derceto realized that she had slept with a mortal and gave birth to a mortal daughter, she killed the man and abandoned the newborn on some sort of rocky outcropping, then threw herself into a lake, where her humiliation was complete when Aphrodite changed her body into the body of a fish. However, according to Diodorus’s telling, where the baby had been abandoned, quote,

1:47 “a great multitude of doves had their nests, and by them the child was nurtured in an astounding and miraculous manner; for some of the doves kept the body of the babe warm on all sides by covering it with their wings, while others, when they observed that the cowherds and other keepers were absent from the nearby steadings, brought milk there from in their beaks and fed the babe by putting it drop by drop between its lips. And when the child was a year old and in need of more solid nourishment, the doves, pecking off bits from the cheeses, supplied it with sufficient nourishment. Now when the keepers returned and saw that the cheeses had been nibbled about the edges, they were astonished at the strange happening; they accordingly kept a look-out, and on discovering the cause found the infant, which was of surpassing beauty. At once, then, bringing it to their steadings they turned it over to the keeper of the royal herds, whose name was Simmas; and Simmas, being childless, gave every care to the rearing of the girl, as his own daughter, and called her Semiramis, a name slightly altered from the word which, in the language of the Syrians, means "doves," birds which since that time all the inhabitants of Syria have continued to honour as goddesses.”1

2:50 End quote.

2:51 So, Semiramis grew up in this pastoral haven. When she was a young teenager, an officer from the court named Onnes was sent to inspect Simmas’s royal herds and fell in love with his adopted daughter. He convinced Simas to let him marry Semiramis, and off they went. This is when Semiramis showed a touch of divine power–not only had she grown up to be very beautiful, but she also had a way of ensnaring men’s attention so that she could convince them to do almost anything. Predictably, Onnes became completely unable to do anything without her guidance, but because her guidance was good he became very prosperous.

3:25 Years later, the king of Assyria and founder of Ninevuh, Ninus, went to war with Bactriana, a kingdom he wanted to conquer. Onnes, by then a trusted officer in Ninus’s army, was sent to lead a faction in the siege of the capital city, Bactra. The siege was long, and Onnes, unable to be parted from Semiramis for such an extended period of time, sent for her to come to Bactriana and advise him in the siege.

3:49 Semiramis, quote, “endowed as she was with understanding, daring, and all the other qualities which contribute to distinction, seized the opportunity to display her native ability.”2 First, in order to travel there safely, she created a new type of clothing which would make it impossible to distinguish whether she was a man or a woman. The clothing allowed her to travel safely and, quote, “do whatever she might wish to do, since it was quite pliable and suitable to a young person, and, in a word was so attractive that in later times the Medes, who were then dominant in Asia, always wore the garb of Semiramis, as did the Persians after them.”3 According to a historian at the University of Chicago, this outfit that she invented apparently covered the head, and consisted of a long coat with large sleeves, loose trousers, and boots.4 It was, apparently, not well-liked by the ancient Greeks because it seemed too effeminate to them.5

4:37 When she arrived, Semiramis found her husband and Ninus’s army to be at something of a standstill. Not content to simply advise her husband on how to effectively win this siege, Semiramis used her new clothing to disguise herself as a soldier and led another group of soldiers to climb a steep and rocky area that no one else had dared to climb. By entering the city this way, they were able to take enough of the capitol that the other king surrendered and Ninus’s war was won.

5:02 At first, Ninus was amazed and grateful to this woman who had basically single-handedly won him this conquest when all his trusted generals couldn’t. And then, the more he got to know her, he fell in love with her. He approached Onnes and begged him to allow Ninus to marry her, even offering his own daughter’s hand in marriage, which would have made Onnes a prince who could have inherited the throne himself someday. But Onnes was not impressed and loved his wife, so he said no. So then Ninus threatened to “put out his eyes” if Onnes didn’t give up Semiramis.6 Onnes, either out of fear or love, hanged himself and Ninus was free to marry Semiramis. She was now queen of the Empire of Assyria.

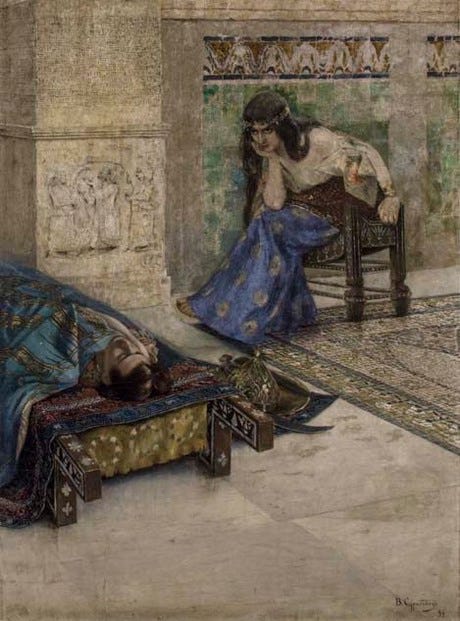

5:39 Together, they had a son, Ninyas, and then almost as quickly as he’d fallen in love with her, Ninus died. According to Diodorus, Ninus left his wife the throne and she simply ascended as queen. But others say that Semiramis disguised herself as their son to take control of the throne herself. It wouldn’t have been possible for a woman to ascend to the throne in ancient Assyria, but Diodorus doesn’t really address this or how she got around it. Maybe we’re supposed to assume that it was, like, her powers of persuasion from, like, her divine bloodline that let her ascend? I’m not sure.

6:10 Nevertheless, Diodorus tells us how Semiramis used her new position and wealth to either build or restore the city of Babylon. She built grand palaces, reservoirs for drinking water, walls to confine the Euphrates River, and temples to Zeus, who the Babylonians called Belus. Diodorus even gives her credit for the famous Hanging Garden of Babylon, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. She built other trading posts and other cities to encourage trade. Once her capitol was established and her power centralized, it’s said that she toured around the kingdom of Assyria. Then, she began to expand it, conquering large swaths of Europe, Asia, and Africa, going into the modern-day Balkans and modern-day China, and extending as far southwest as modern Egypt, Libya, and Ethiopia.

6:54 While in Egypt, she apparently sought out the oracle of Ammon, asking how she would die. She was told that, quote, “she would disappear from among men and receive undying honour among some of the peoples of Asia, and that this would take place when her son Ninyas should conspire against her.”7 She left, and after this, she tried to conquer India, but she lost nearly ⅔ of her military force, was very badly wounded, and had to return back to Babylon at a loss.8

7:18 When she returned home, her son conspired against her through a, quote, “certain eunech” though the man is never named.9 Rather than arrest him or punish him in any way, she willingly turned the kingdom over to him, commanding that her governors obey him. And then Semiramis disappeared. Some say that she became a dove and flew away, back to the creatures who had cared for her during infancy. Others say she ascended to the heavens to be among her divine brethren. Her son Ninyas ascended to the throne and ruled peacefully over the empire his parents had established for thirty years.

7:48 Semiramis was said to be 62 years old at the time of her disappearance and had ruled for 42 years. That’s the legend, at least, according to Diodorus.

7:58 Now, he’s not the only one. Over 80 different ancient writers mention Semiramis in some way. For instance, Roman historian–Oh, I’m going to pronounce this wrong and I’m sorry in advance–For instance, Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus credits her as the first ruler to castrate a male youth and make him a eunuch.10 Armenian tradition presents her more negatively, saying that after the death of Ninus she fell in love with the Armenian King Ara the Handsome. When he refused to marry her, she invaded Armenia and he was killed.11

8:27 So clearly, her story–or at least her existence–was well-known, but the retellings of her story and these embellishments on it obscure a lot of the reality around her. Because we do know that some version of her was real. I actually suspect that some of these embellishments were created by her during her lifetime. I mean, I get it–everyone wants to rewrite their origin story to be more glamorous, right? But, c’mon, doves feeding her for a year? I have my doubts.

8:55 But I say that she probably encouraged some of this myth-making herself because giving herself a divine bloodline and building up her reputation with stories like being raised by doves and single-handedly conquering a city would have been important for her to centralize power around herself. After all, if she could make it look like it was divine will that she ruled over Assyria, then questions around whether women could rule became less important. How do you argue with the gods?

9:24 Right after this break, we’ll take a look at the more historical version of Semiramis, or Shammurammat .

9:35 All right, and we’re back.

9:37 First up: the confusion around her name (Semiramis versus Shammurammat) stems from thousands of years having passed, plus repeated translations back and forth through time. Semiramis may be a Greek-language disambiguation of Shammurammat, which is a Hellenized version of the Assyrian pronunciation. From the research I did, it seems like her real name might mean “high Heaven,” but no one is quite sure.12

10:01 Britannica’s entry on her is short, and focuses on the legend that Diodorus told of her, which, as you know, I just went over. All that is accepted as fact, at least by the encyclopedia, is the following. Quote,

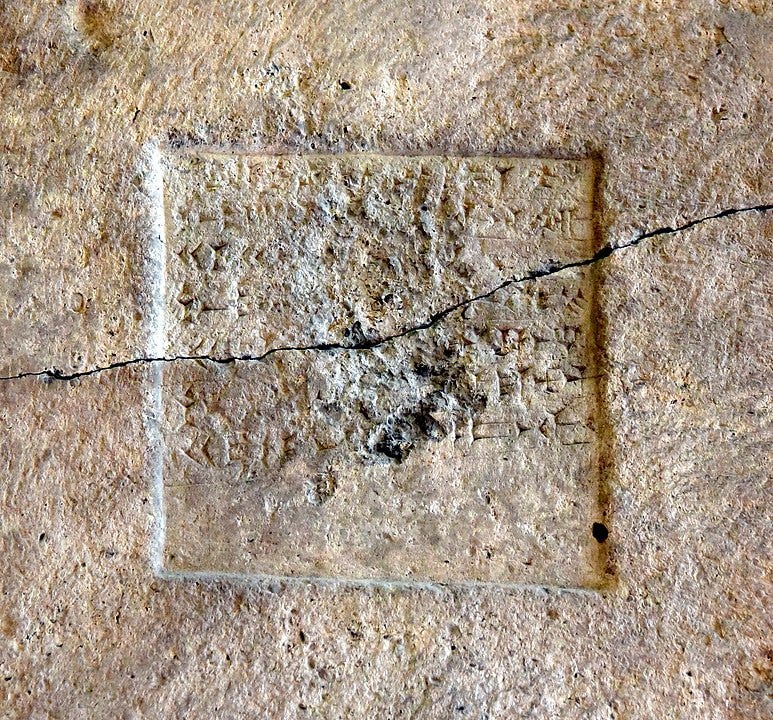

10:14 Sammu-ramat was the mother of the Assyrian king Adad-nirari III (reigned 810–783 BC). Her stela ([or] memorial stone shaft) has been found at Ashur, while an inscription at Calah (Nimrūd) shows her to have been dominant there after the death of her husband, Shamshi-Adad V (823–811 BC).13

10:37 As you probably noticed, there’s no mention of divine lineage or doves here. Her background isn’t well-established at all, and some historians tend to think that she was probably like a princess of a smaller kingdom whose name has been lost to time.

10:48 One thing we do know for sure is that she entered the historical record at a pivotal time. According to National Geographic, quote, “Her husband was the grandson of Assyria’s great ruler, Ashurnasirpal II, a flamboyant monarch who built a magnificent palace at Nimrud in the early ninth century B.C. This event is commemorated by the Banquet Stela, which recorded thousands of guests and a celebration that lasted for 10 days. Ashurnasirpal II stabilized the empire, putting down revolts with a level of cruelty that he made no attempt to hide.”14 When Shammuramat’s husband Shamshi-Adad ascended to the throne, he had to defeat his rebellious older brother.15 The empire was weakened by internal strife, and by the time he died in 811 BCE the financial and political weaknesses of the empire were great enough to actually threaten its future. Adad-nirari would have been too young to rule and needed some kind of regent or guidance.

11:38 It’s unclear whether Shammurammat actually became a formal regent or if she just, sort of, was very powerful and therefore influenced a lot of things. Either way, it’s very clear that in the years between the death of her husband and her son becoming old and mature enough to actually rule on his own, Shammurammat was very very influential.

11:58 The stele that Brittanica noted is important though because it tells us just how important this woman was. It was a stele that her that son dedicated to her, and it explicitly lists her as his mother, which in addition to just being a little touching, was also very out of the ordinary. Lineage in Ancient Assyria, like many other places, was determined through the paternal line–a mother’s name was often not recorded because it didn’t matter, especially for things like determining a king’s lineage. But the stele reads, quote,

12:27 Sammu-ramat, Queen of Shamshi-Adad, King of the Universe, King of Assyria; Mother of Adad-nirari, King of the Universe, King of Assyria.16

12:36 Obviously, she was too important to have been ignored. The queens of the Neo-Assyrian Empire did hold some power on their own. They controlled their own finances and often owned estates in the empire. They hired their own staff, which were usually overseen by female administrators called šakintu. Queens were also responsible for a lot of religious activity, sponsoring temples and ensuring that the gods were being honored correctly.

12:57 But Shammurammat seems to have been uniquely powerful even by this standard. Not many Queens joined military campaigns, and it is agreed upon by a lot of historians that Shammurammat at least joined her husband and son on military campaigns, if not actually led her own. But the Kizkapanli stela mentions, quote, “that the queen accompanied her son when he crossed the Euphrates River to fight against the king of the Assyrian city of Arpad. Her presence was unusual for the time, and the fact that the stela bothers to mention her participation gives Shammurammat’s actions a strong degree of honor and respect.”17 So, I mean, this is proof that she also really did wield power at least similarly to a regent, though probably not for the 42 years that Diodorus proposed. It’s more likely that she was regent for about 5 years.18

13:41 Unfortunately, that’s about where our confirmed knowledge of her ends. But something about Shammurammat sticks in our minds, and her name and likeness have been used throughout time as a shorthand for all sorts of ideologies. Historians, artists, and anyone with an agenda stumbles across her occasionally and brings her into the conversation. Sometimes she’s cast as a powerful feminist icon and other times she’s the Whore of Babylon. Literally.

14:05 Sometime during the Middle Ages, the legend of Semiramis suddenly became associated with promiscuity and lust. A Roman priest and historian, Orosius, wrote about her in his history Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, which is just [sighs] 4th-century propaganda. He claimed that she had an incestuous relationship with her son, something no one else was claiming. But then a thousand years later, maybe influenced by Orosius, Dante included her in his Divine Comedy among the souls of the lustful in the Second Circle of Hell. She’s also mentioned by Shakespeare in both Titus Andronicus and The Taming of the Shrew.

14:48 During the Renaissance, her reputation did partly recover, but she’s weirdly still a subject of discussion in deeply evangelical circles. In 1853, Christian minister Alexander Hislop wrote about her in his book The Two Babylons, casting her as the Whore of Babylon. He claimed that she invented polytheism and that the head of the Catholic Church (then Pope Pius IX) was continuing a millennia-long secret conspiracy founded by Semiramis and the Biblical King Nimrod to bring back the religion of ancient Babylon. He claimed that Semiramis was Nimrod’s mother and had encouraged him to build the Tower of Babel and that they had had an incestuous relationship and their child was the deity Tammuz, or Dumuzid, an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with shepherds. Critics and historians have dismissed all of this as speculation, fear-mongering, and Hislop trying to write about a culture based on texts that he literally didn’t understand because he couldn’t read the language. However, this version of this myth is still accepted among evangelical Protestants and circulates today. But I want to be clear: It was based on the speculations of some dude who couldn’t read the language he was sourcing from. It’s crap. There’s no supporting evidence for Hislop’s claims and nothing in the historical record ties her to Nimrod. At all.

15:43 However, these claims have influenced how she’s been portrayed in recent pop culture. There was a 1954 film called Queen of Babylon that portrayed her as one of love’s seven wonders of the ancient world. Zero points for guessing how overly sexualized she clearly was in it. I mean, it sounds like porn, right? Then in 1963, a film called I Am Semiramis takes the legend Diodorus wrote and runs with it, casting her as in love with a slave named Kir who she forces to help build the city of Babylon. There’s a rebellion, and from the summary, it seems like everyone dies, though to be clear I haven’t watched it.

16:38 And that’s sort of the story of Semiramis! Like I said, it’s pretty shrouded in mystery and there are more questions than there are answers. But it’s clear that she was influential in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and her name, and the legend of her, lives on. I hope you enjoyed this episode of Unruly Figures! If you did, tell at least one friend about it, that really does help.

📚Bibliography

Books

Siculus, Diodorus. Library of History. Vol. 2, Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press ; London : W. Heinemann, Ltd., 1967. https://archive.org/details/diodorusofsicily0001diod/page/358/mode/2up

Websites

Gutiérrez, Marcos Such. “The True Story of Semiramis, Legendary Queen of Babylon.” National Geographic - History, National Geographic, 3 May 2021, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/searching-for-semiramis-assyrian-legend.

“Sammu-Ramat.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sammu-ramat.

“Semiramis.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Apr. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semiramis#cite_ref-30.

“Semiramis: Other Ancient Traditions.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Apr. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semiramis#Other_ancient_traditions.

Thayer, Bill. “Diodorus Siculus - Book II (Beginning).” Diodorus Siculus - Book II Chapters 1‑34, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/2A*.html#note11.

Siculus, Diodorus. Library of History. Vol. 2, Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press ; London : W. Heinemann, Ltd., 1967. https://archive.org/details/diodorusofsicily0001diod/page/358/mode/2up

Diodorus, 367

Diodorus, 367-369

Thayer, Bill. “Diodorus Siculus - Book II (Beginning).” Diodorus Siculus - Book II Chapters 1‑34, https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diodorus_Siculus/2A*.html#note11.

Thayer

Diodorus, 369

Diodorus, 397

Diodorus, 417

Diodorus, 417

“Semiramis.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Apr. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semiramis#cite_ref-30.

“Semiramis: Other Ancient Traditions.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 4 Apr. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semiramis#Other_ancient_traditions

Gutiérrez, Marcos Such. “The True Story of Semiramis, Legendary Queen of Babylon.” National Geographic - History, National Geographic, 3 May 2021, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/history-magazine/article/searching-for-semiramis-assyrian-legend.

“Sammu-Ramat.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sammu-ramat.

Gutiérrez

Gutiérrez

Gutiérrez

Gutiérrez

Gutiérrez

I call 'Whore of Babylon' for all future screen names!