Jean-Michel Basquiat: Transcript, Bibliography, & Photos

A look at one of the most famous artists of the 1980s

Thanks for checking out Unruly Figures! I’m able to keep these transcripts, bibliographies, and more free because of the amazing people who help support this work. Want to support independent and in-depth research? Subscribe now!

🎙️ Today I’ve got the transcript and bibliography for Unruly Figures episode 2, Jean-Michel Basquiat. At the beginning of each paragraph is a time code for where you can find that in the episode. I also do endnotes throughout, in case you want to follow up with a resource for more reading!

Word to the wise: If you’re listening anywhere other than on Substack, the time codes will start to be off about halfway through. That’s because everywhere else has ads but Substack subscribers get ad-free episodes. Add about 2 minutes to the time codes here to find them in the episode where you’re listening.

Transcript

👋🏼 Introduction

0:06 Hi everyone! Welcome to Unruly Figures. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today we’re going to be talking about one of my favorite artists--Jean-Michel Basquiat.

0:14 According to many, Basquiat is one of the most significant painters of the 20th century. His arrival on the fine art scene in the 1980s was a turning point in the establishment. He was part of the Neo-Expressionism movement but was also beyond it. I’m going to be honest—it intimidates me a little to cover Basquiat. I researched him once before, when I worked as a curatorial assistant at a museum, and so much of the material out there covers the cult of personality that developed around him. It makes him almost mythical, a god of art walking amongst us mere mortals. Even essays that claim to be serious art criticism of his paintings are more about Basquiat himself, and the obsession that people felt about him. Of course, this is perfect for me now, since I’m no art critic and I just want to tell you guys about him.

1:00 Lately, there’s been a resurgence in interest around him. His work is broken apart into symbols and put on t-shirts and purses at every level of commercial production from Target to Doc Martens to Barbie to Coach. Before it sounds like I’m criticizing anything to do with this, let’s be clear: I own a Coach purse with Basquiat’s famous Pez Dispenser t-rex on it, and I would have bought those Doc Martens if they hadn’t been sold out in my size. I’m a fan, so if it sounds like I’m occasionally fangirling here… well, I am.

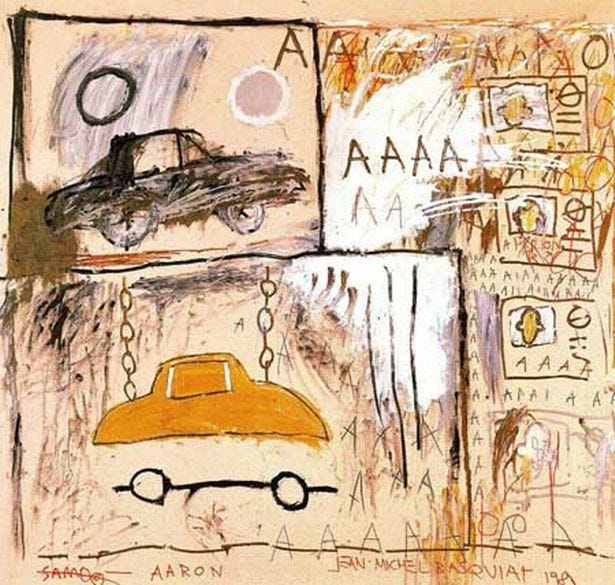

1:27 Obviously, podcasting is an auditory medium, so I can’t show you any of Basquiat’s art here. But go to the Unruly Figures Substack to check out several of his major works of art. That’s UnrulyFigures.Substack.com, again U-N-R-U-L-Y-F-I-G-U-R-E-S dot S-U-B-S-T-A-C-K .Com. All right, let’s hop in.

🧒🏿Biography

1:53 Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn on December 22, 1960 to a Puerto Rican mother named Matilde Basquiat, née Andredas, and a Haitian father, Gérard Basquiat. Their first son, Max, had already died when Basquiat was born, and he was followed by two sisters, Lisane and Jeanine. As a result of this mixed heritage, he was fluent in Spanish and French, in addition to English. He displayed a talent for art early in his childhood, so his mother often took him to museums and galleries. When he was just six, she signed him up as a Junior Member of the Brooklyn Museum, which is just precious to me. She encouraged him to learn to paint and draw, and he did so using whatever supplies they could get their hands on, including scrap paper that his father brought home from his job as an accountant. He was also a really good athlete. He competed in track events while in school.

2:42 In 1967, Basquiat was enrolled at St. Anne’s School, a famous humanities-oriented private school in Brooklyn Heights. There, he had his first collaboration. He made friends with a boy named Marc Prozzo, and together they made a children’s book. Basquiat wrote the story and Prozzo illustrated it.

2:58 Now, at either six, seven, or eight-years-old, he was hit by a car while playing in the street. (And yes, there is debate about his age when this accident happened!) He suffered several injuries, and had to have his spleen removed. Matilde gave Jean-Michel a copy of Gray’s Anatomy to read while he recovered. Yes, the medical textbook. Everyone cites this story because people believe this was formative to his visual style--his humans aren’t always anatomically perfect, but he often drew disembodied feet on his canvases, the way that they are presented in a medical textbook. Gray’s Anatomy is also apparently a very stock piece of art school literature. Artists use it to learn how to put bodies together.

3:42 The same year as his accident, Jean-Michel’s parents either separated or divorced. A couple of years later, when Basquiat was either 10 or 13 (seriously, it’s surprisingly hard to nail down a timeline for his childhood), his mother was hospitalized for a mental health issue. She spent the rest of her life in and out of institutions.

3:59 When he was 15, Basquiat ran away from home for the first time. He slept in Washington Square Park for a week before he was found, either by his father or by police. When he was returned to his father’s care, Basquiat allegedly told him for the first time, “Papa, I will be very famous someday.”1

4:15 Citing physical abuse from his father, Basquiat ran away from home again at some point, and was taken in by a friend’s family. At 17, he dropped out of his public high school and started attending City-As-School, which was geared toward kids who were artistically talented and bright but struggled with conventional education.

4:31 At City-As-School, Basquiat met Al Diaz, who he became friends with and collaborated with artistically. In a 2017 interview for Dazed, Al Diaz had this to say of Basquiat:

“He was shy around the more aggressive types, like the skateboarders or the graffiti artists. He wasn’t a tough guy or anything. But with his own circle of friends, he was pretty outgoing. Somehow, we really hit it off [because] we just kind of had the same sense of humour.” (As a side note, the two shared musical and artistic interests, and both had Latinx heritage.) Diaz continued, “It was enough to cement our friendship. We were both big on words and language, and that really did it. I don’t know if we were aware of it at the time, but it was definitely something.”

5:10 Diaz described a class they took together:2

“If you needed art credit, you could do a course where you would go to MoMA, or something, and Jean and I did that class together. But he was real problematic – he was always arguing with this woman called Sylvia, who conducted the tours. I always wondered if she remembered a young Jean-Michel and later on put two-and-two together and thought, ‘oh fuck, that guy became famous.’”

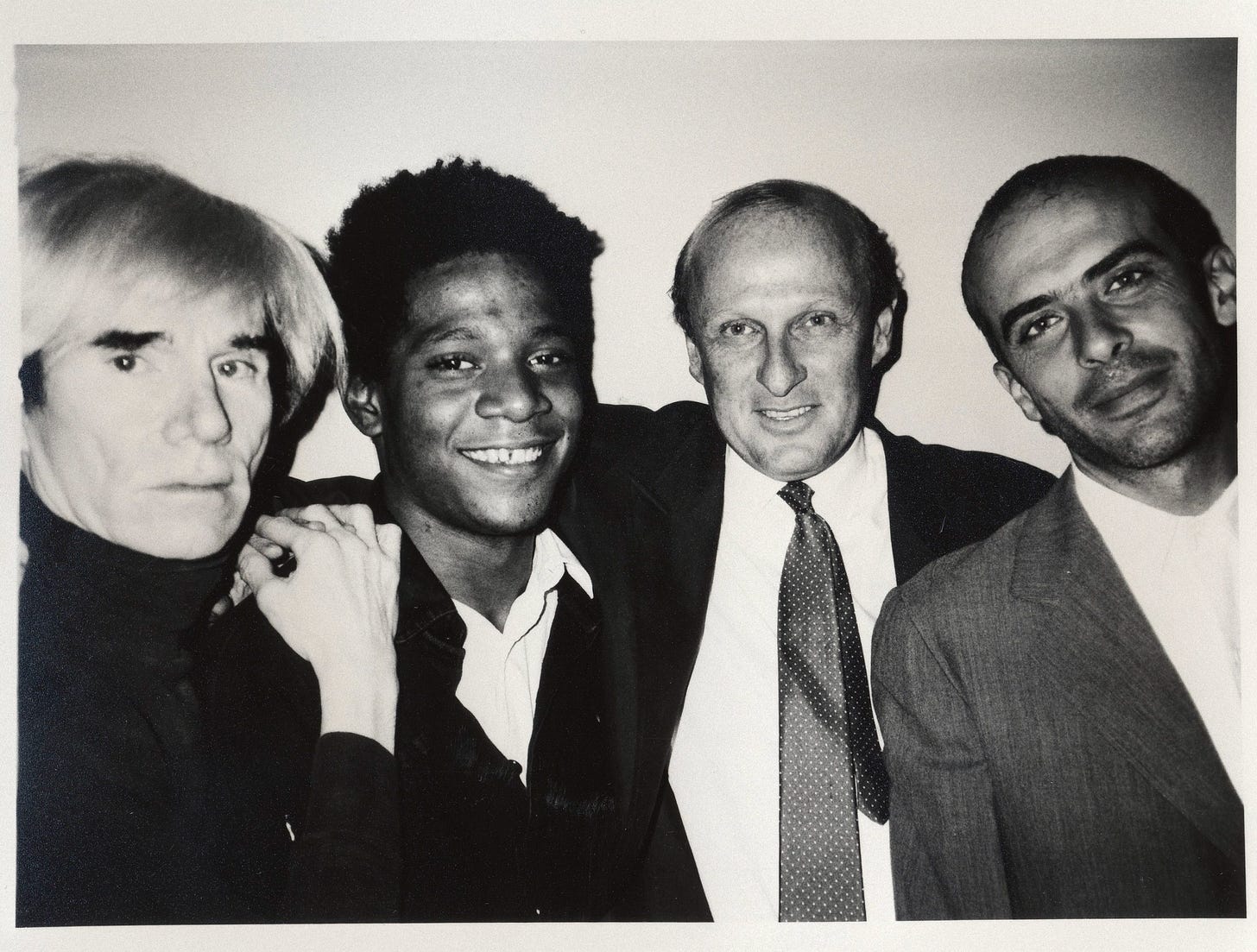

5:31 In the late 1970s and early 1980s, working across different media—film, painting, performance, music—was widespread, and so was working collaboratively. Andy Warhol was a role model of this practice. Since the 1960s, he had been working across painting, drawing, photography, sculpture, film, fashion, performance, theatre, music, and literature. He overcame traditional barriers between disciplines and cultural scenes and became a huge role model for Basquiat. It was probably with Warhol as a sort of a guiding star that Basquiat began creating with others.

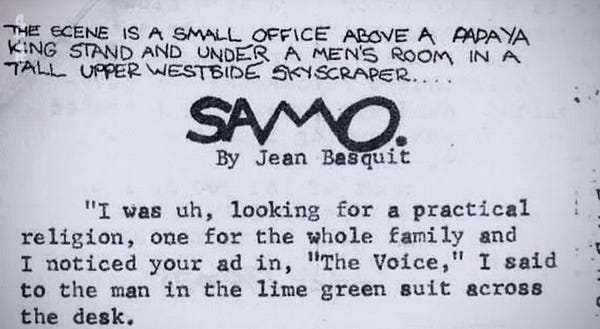

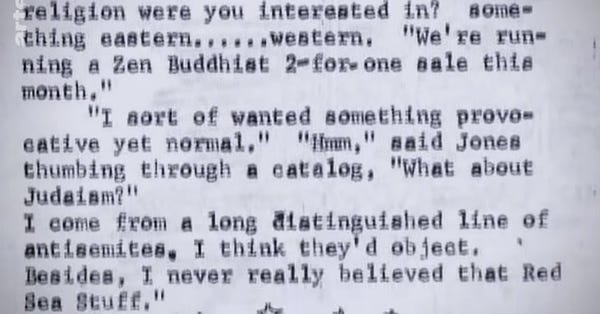

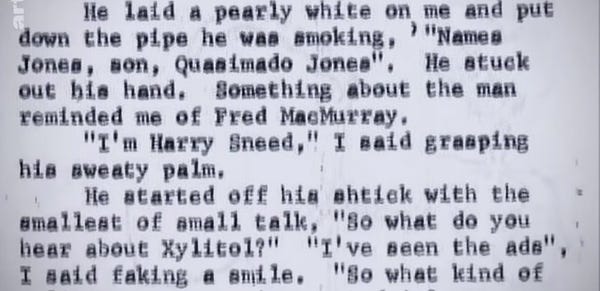

6:04 First, Diaz and Basquiat, along with some other friends, created a newspaper called Basement Blues Press. It was while writing an article for the Spring 1977 issue that Basquiat first conceived of SAMO©--spelled S-A-M-O in all caps. The article featured a fictional conversation between author Harry Sneed and someone named Quasimodo Jones, in which Sneed is searching for a new religion for the whole family. Jones sells him on SAMO©, the ideal religion because it’s guilt-free. A few days after they wrote the article, Diaz and Basquiat handed out flyers with fake testimonials from people who had converted to SAMO©. “We thought it was hilarious. We were just kids,” explained Diaz.3

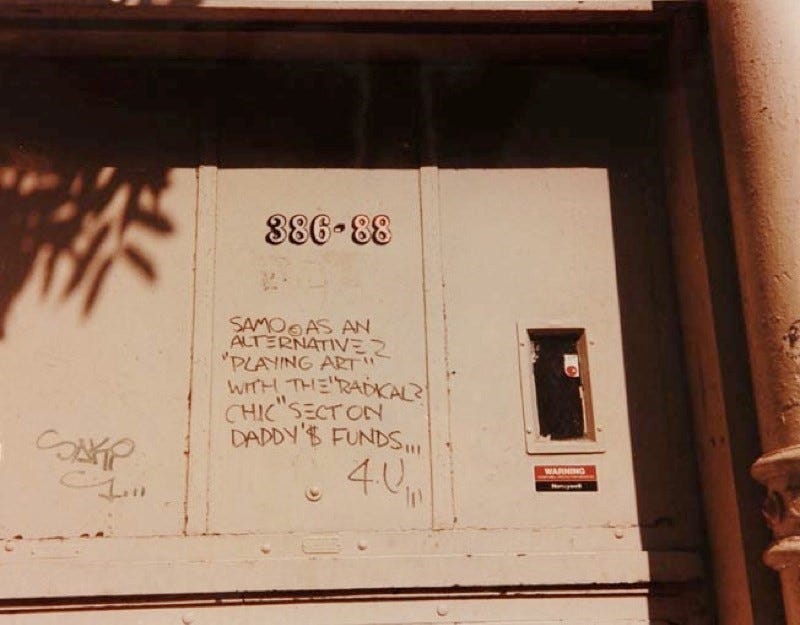

6:43 They liked SAMO©--short for Same Old Shit--enough that they kept running with it. They started using it to tag graffiti together, marking buildings across New York City with inside jokes, teenage frustrations, and provocative statements that people noticed. Like all good artists, Diaz noted that they were communicating with other artists through their work. He said, quote, “There was a famous graffiti artist that always wrote, quote, ‘Pray and Jesus Saves,’ end quote, and all these kinds of religious things, and I thought we could go about it in that style. We just kept elaborating on it. In a couple of weeks, it was like ‘SAMO© AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO GOD’.” Whereas most street art, at that time, was mostly about tagging--putting your name or a symbol on a wall--what Basquiat and Diaz did was comment on the world around them. They were very much ahead of their time in this way.

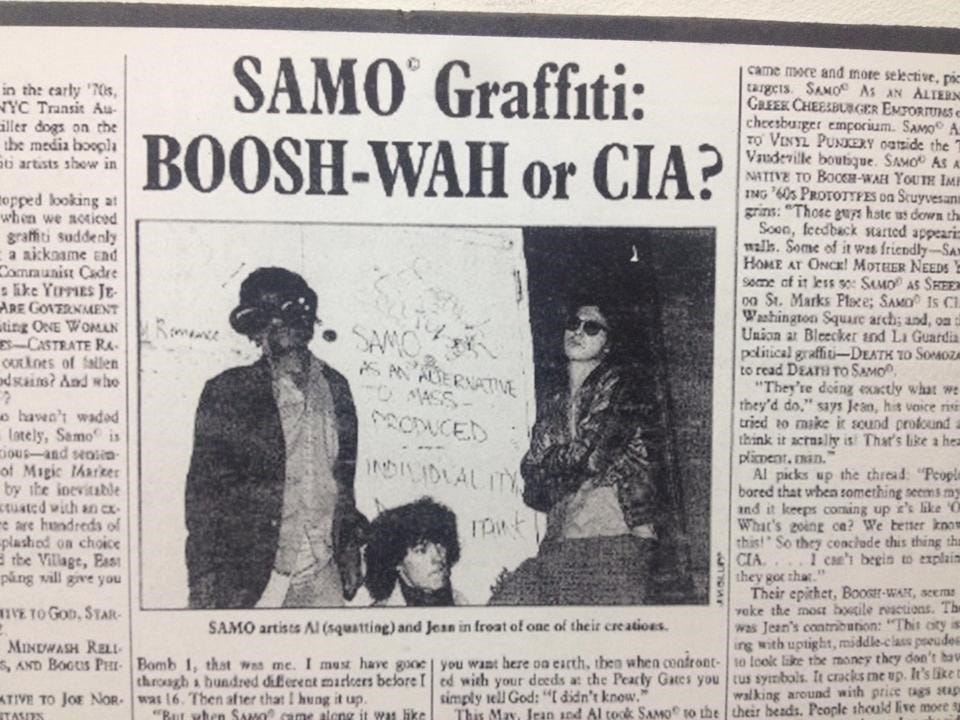

7:30 They stayed largely anonymous behind SAMO© until December 1978, when they sold their story for $100 to the Village Voice. The article, titled, quote, “SAMO© Graffiti: BOOSH-WAH or CIA?” asked them to expound on what SAMO© was really about: Basquiat explained, “SAMO© is just a means of bringing it out. A tool for mocking bogusness… We can’t stand on the sidewalk all day screaming at people to clean up their acts, so we write on walls.” (And if you’re thinking that that sounds a little bit like Holden Caulfield, I agree! I imagine Basquiat read The Catcher in the Rye at some point.) The article also revealed the attention they received at the time, as people wrote their own responses to SAMO©, like “SAMO© CALL HOME AT ONCE! MOTHER NEEDS YOU.” The article was titled “BOOSH-WAH or CIA” because people had begun to believe that it was part of a larger CIA conspiracy. I mean, which, I suppose, if you’ve read anything about what the CIA was up to in the 1970s and 80s, I mean, I guess, graffiti in New York City would be tame by comparison. The article ends with the observation that the pair’s social circle was, quote, “worried that a taste of fame would go to their heads.”4

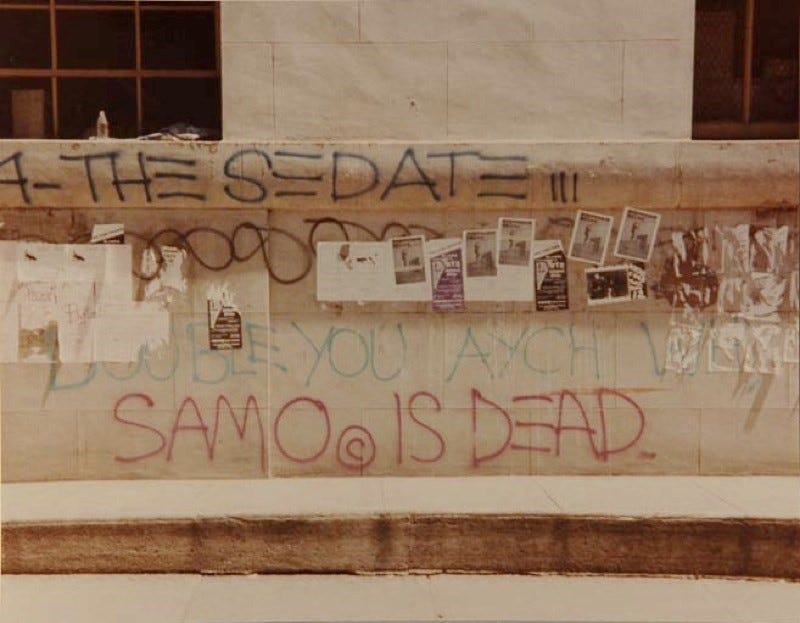

8:35 While the article didn’t single-handedly vault Basquiat into international fame, it was certainly the start. Around this time, Basquiat started hanging around the School of Visual Arts, which is how he befriended another hugely famous artist, Keith Haring. In 1979, Basquiat appeared on Glenn O’Brien’s off-the-wall TV show, TV Party. On the show, he called himself SAMO©, even though Al Diaz wasn’t there. Basquiat ended up appearing on the show several more times. In April of 1979, Basquiat met a musician named Michael Holman at a party and they founded their industrial band Gray, as a reference to Gray’s Anatomy, with a few others. The band played at several big downtown venues. By mid-1980, Diaz and Basquiat had had a falling out and stopped working together. Basquiat spray-painted the phrase “SAMO© IS DEAD” on several galleries in SoHo to announce it, and Keith Haring staged a mock wake for SAMO© at Club 57.

9:30 Around this same time, Basquiat started painting and selling postcards on the street. You’ve seen one of these postcards if you ever watch Pawn Stars, because someone walked into their shop and sold them two original Basquiat postcards for $50,000. While selling postcards one day in SoHo, Basquiat spotted Andy Warhol having lunch with art critic Henry Geldzahler and managed to sell him one of his postcards. As I already mentioned, I think, Warhol was a bit of a role model to Basquiat. And, as we’ll see, this wasn’t the last time they’d meet.

9:58 1980 is the year Basquiat’s life took a noticeable turn. After the end of SAMO©, Diaz went on to stay in music and largely in the underground art scene of New York, and Basquiat began his solo career, which did vault him to new heights of fame. He participated in the hugely famous The Times Square Show in 1980, which was a groundbreaking show because it was one of the first exhibitions to manage to transcend the boundaries of race and class that had long separated out gallery artists from other artists. Open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week in Times Square, it brought people from across cultures and classes together in a way that they normally would not have interacted. Other famous, quote, “establishment” artists such as David Hammons and Keith Haring participated in it as well. The next year, Basquiat’s work was exhibited in New York/New Wave as P.S.1, another hugely famous show because, in retrospect, it marked a moment of generational change in the art world.5

11:15 It’s also around this time that the mythologies of Basquiat began to crop up. People look back and compare him to Jimi Hendrix in terms of pace of output, lasting impression on culture, and early death. This desire to mythologize him is probably why nailing that early childhood timeline was so difficult. So far, I’ve been relying a lot on general biographies of Basquiat, of which there are many, but honestly the Wikipedia page for him is, like, surprisingly detailed and well-cited, if you want a starting place. For a lot of the work that comes next, I’m leaning heavily on Dieter Buchhart--and I’m really sorry if I’m pronouncing that incorrectly, I couldn’t find a proper pronunciation online. So I’m leaning heavily on Dieter Buchhart, a curator and Basquiat scholar who put together the exhibition Boom For Real in Britain in 2017. Buchhart’s goal was to strip away a lot of the mythology and look for what made Basquiat a great artist, independent of the drugs, fame, and soaring prices of his paintings. I’m going to try, from here on out, to interweave big moments of his artistic career, with thoughts from scholars, as well as the big moments of his personal life.

12:17 So, even though, as I said, Basquiat was still participating in a lot of interdisciplinary media, 1980/1981 is when we really start to think of Basquiat as a ‘gallery artist.’ A capital-A Artist. While the Village Voice article was his first big publication mention, it was art critic Jeffrey Dietch who gave Basquiat his first art world establishment mention. After seeing his work at the 1980 The Times Square Show, Dietch mentioned Basquiat by name in an article titled, “Report From Times Square” in the September 1980 issue of Art in America. It was the beginning of a hugely successful career.

12:52 Though SAMO© was over, Basquiat never stopped using words in his art. Importantly though, he rejected the label “graffiti artist.” Klaus Kertess, an art critic and dealer, described Basquiat’s work as, quote, “words like brushstrokes,” end quote, indicating that they weren’t there as a message, exactly, but as another feature of the painting. Buchhart compared the rhythm they established in his work to the spoken poems of the Dadaists. Rapper Fab 5 Freddy echoes this, saying, quote, “If you read the canvases out loud to yourself, the repetition, the rhythm, you can hear Jean-Michel thinking.”6 End quote. So his art occupies this liminal space between painting and emerging spoken word in hip-hop.

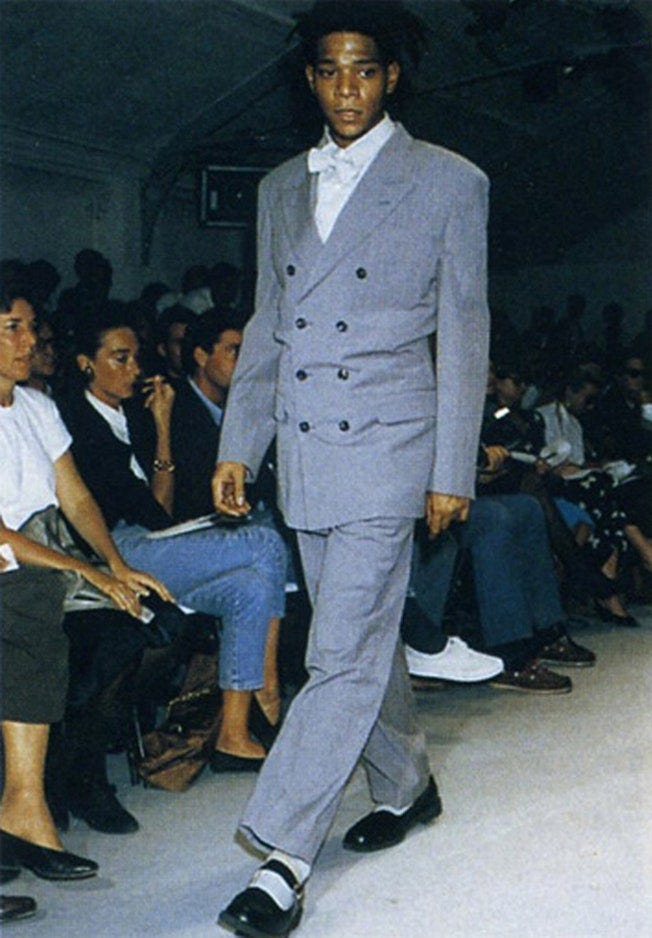

13:34 I want to touch on Basquiat’s fashion sense for a second here. He loved clothes. When he was kid, his mother had designed his own clothes for him, and one elementary school teacher later recalled that his style had always been interesting, and that he’d had pencils sticking out of his hair from a young age.7 He was very experimental with the way he dressed; he sometimes wore like a mismatched blazer and trousers with a striped shirt and a clashing tie, or like maybe a loudly patterned shirt with a leather jacket, stuff like this. Around this early point in his career, he was actually upcycling clothing with designer Patricia Field, painting on sweatshirts for her. American curator Diego Cortez described spotting him in a New York club once, saying, quote, “I remember on the dancefloor seeing this Black kid with a blond mohawk. He had nothing to do with Black culture. He was this Kraftwerkian technocreature … He looked like a Bowery bum and a fashion model at the same time.”8 British GQ style director, Robert Johnston, once theorized that Basquiat’s look helped make him famous. He said, quote, “While meaning no disrespect to his talent, it is hard to imagine he would have taken New York so much by storm if he’d looked more like Francis Bacon.”9 Which, honestly, just seems mostly rude to Francis Bacon.

14:49 But, regardless of his fashion sense, in 1981, Basquiat sold his first painting. He sold it to Debbie Harry, the lead singer of Blondie! I mean, they had acted together in Downtown 81 and he had appeared in one of Blondie’s music videos, so they had an established friendship. But, still, I just think it’s really cool… the first person he sold a painting to was one of the most famous female musicians in American history. So anyway, she paid $200 for Cadillac Moon after filming for Downtown 81 ended. It’s considered a foundational piece of Basquiat’s body of paintings. It’s covered in frenetic drawings that appear child-like but are deceptively complex, as well as words and phrases repeated like a mantra, or maybe a prayer.

15:31 His first one-man show came soon after. An Italian artist named Sandro Chia (or maybe Sandro Chia) had somehow heard of Basquiat’s work and recommended it to Italian art dealer Emilio Mazzoli, who immediately bought 10 paintings for $10,000 so that Basquiat could have a show at his gallery in Modena, Italy in May of 1981.

15:52 And I want to note here that, while he had just made $10,000 from Mazzoli, Basquiat really wasn’t making reliable money yet. In 1981, he was living with his girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk, who financially supported him with her job as a waitress. Mallouk, by the way, is the subject of the book, Widow Basquiat: A Memoir, which is a deceptive title because the two were never married.

16:14 As you can see, he wasn’t an art world star overnight, but he went from anonymously tagging buildings as SAMO© in December 1978, to having a one-man show in May 1981. That’s quite a leap. In December of the same year, art critic Rene Ricard published “The Radiant Child” in Artforum. It was the first article to extensively cover Basquiat as an artist alone. He was 21 years old.

16:39 The fall after Basquiat’s show in Italy, our friend Sandro Chia then--or Sandro kee-ah? I’m sorry, I don’t know how this is pronounced. In any case, Sandro suggested that New York gallery owner Annina Nosei invite Basquiat to be part of her… I don’t know how to describe it. Stable of artists? Artists--big artists--don’t usually just go to just any art dealer or gallery owner every time they paint something new. They usually stick with one, like an actor has an agent. In any case, Nosei met with Basquiat for coffee to get to know him and talk art. At the time, he only had drawings, he couldn’t afford canvases and oil sticks to do bigger work. So she kind of just trusted that he could do it--there’s this amazing interview she did with Jeffrey Deitch where she admits she just believed he could be a great artist, despite not seeing any evidence of that!10 She gave Basquiat money for materials and space to work in the basement of her gallery.

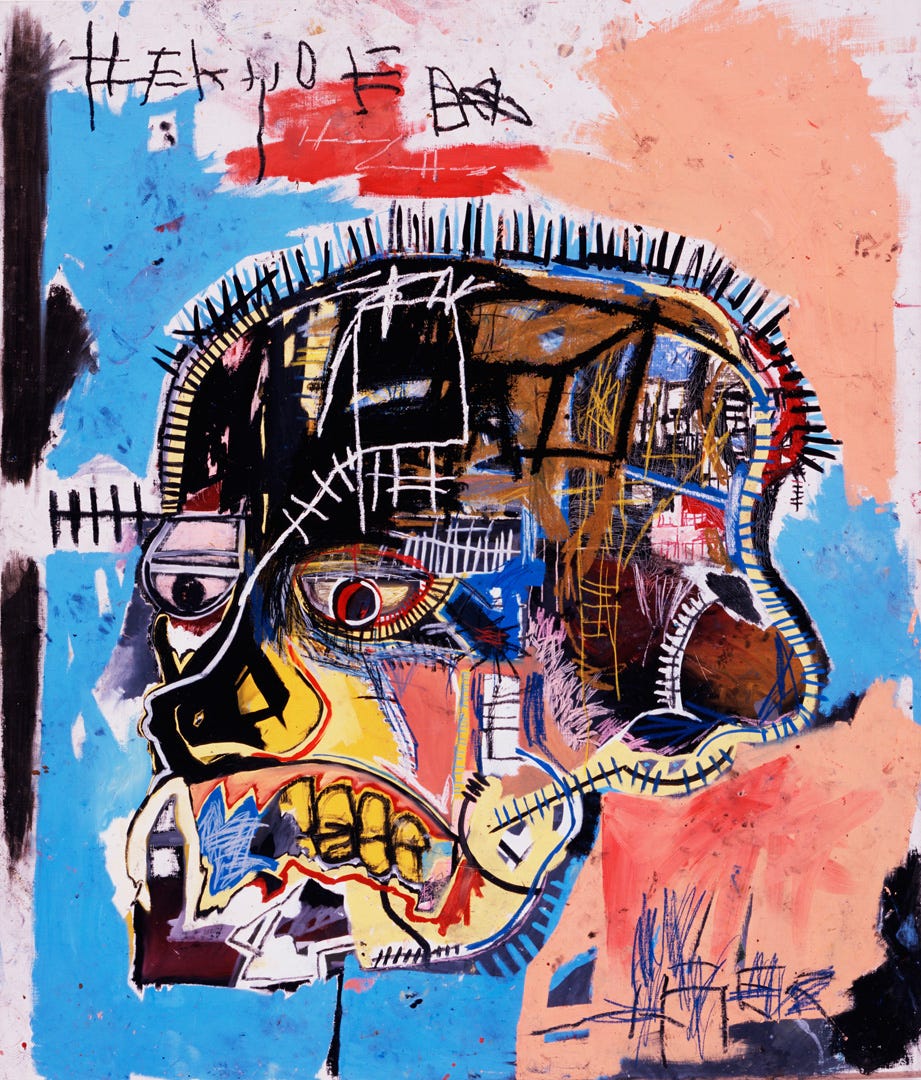

17:59 But it was in Nosei’s basement in 1981 that he started working on a painting that stalled him. It’s called Untitled (Skull) and Basquiat came back to that work over and over again for months. Some, including art historian Fred Hoffman, believe that Basquiat was, quote, "caught off guard, possibly even frightened, by the power and energy emanating from this unexpected image."11 While a lot of his work was in some way autobiographical, in that it often was an extension of things he was thinking about, some think this particular work might be the closest thing we have to a self-portrait of Basquiat.

18:39 Basquiat often used heads and skulls in his work, and sometimes the two would get confused--as is actually the case in this painting. Untitled depicts both inside and outside dimensions of a head, existing between life and death. The eyes are listless, as if the person was lobotomized, or just high. The listless facial expression though is in huge contrast to the vibrant colors in the cranium that suggest an abundance of internal mental activity. Some link his use of heads and skulls to his identity as a Black American and find them to be evocative of African masks; other people compare them to images from Haitian voudou.

19:14 In 1982, Nosei helped him move into a loft-slash-studio in SoHo, presumably because Basquiat and Mallouk had broken up and he was finally making reliable money. Basquiat’s first American one-man show was at Nosei’s gallery in 1982. Basquiat’s first American one-man show was at Nosei’s gallery in March 1982. But by that summer he left Annina Nosei and Swiss art dealer and collector Bruno Bischofberger became his worldwide dealer. “I wanted to be a star, not a gallery mascot,” he said of this transition.12

19:46 In June of that year, at just 21 years old, Basquiat was invited to take part in documenta 7, in Kassel, Germany, which is a hugely important show of contemporary art that takes place every five years. He was the youngest artist in the show’s history, at the time, and his works were shown alongside famous artists like Cy Twombly, Andy Warhol, Anselm Kiefer, and others.

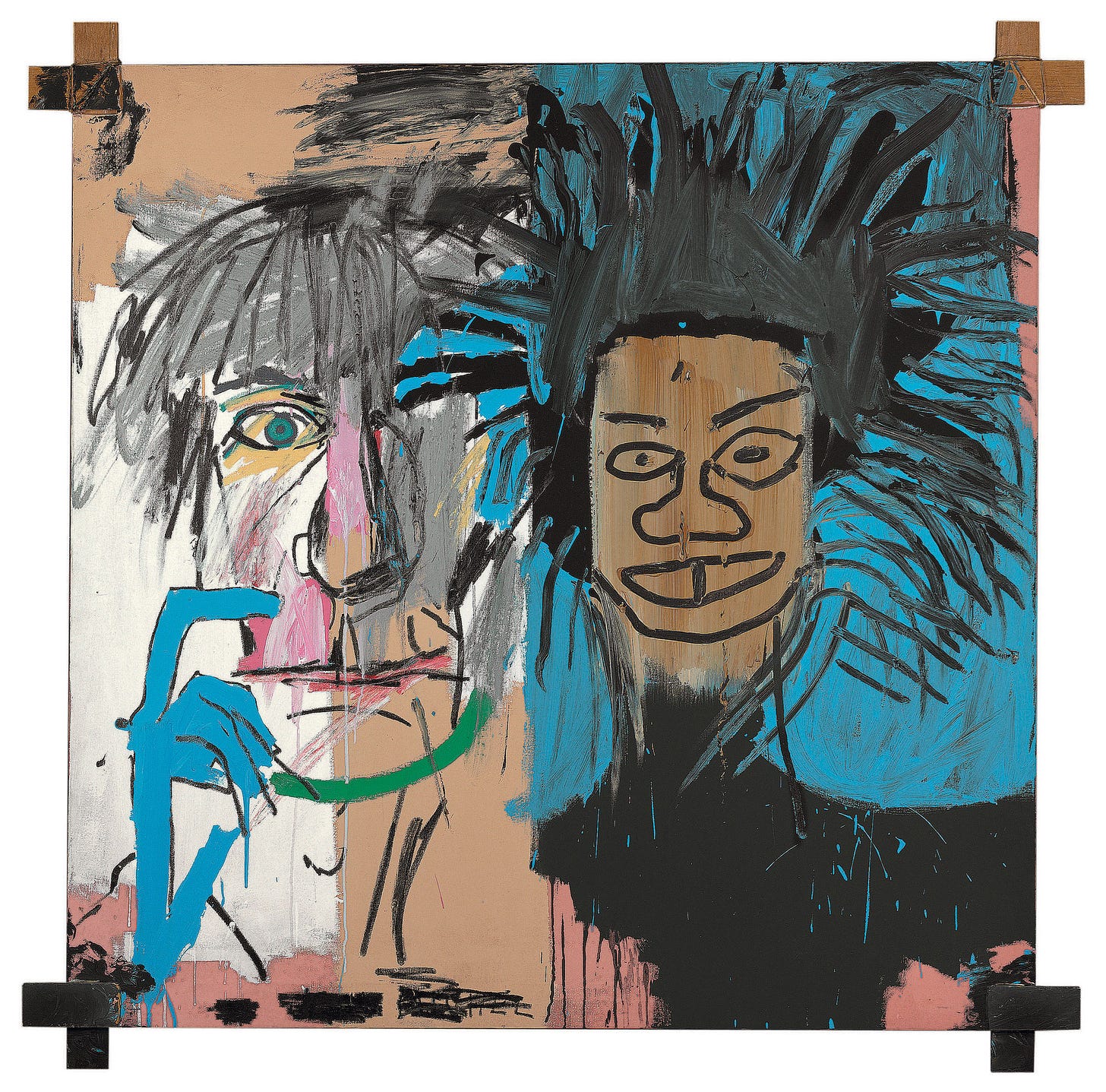

20:07 In October of 1982, Bischofberger introduced Basquiat to Andy Warhol. They had lunch together on October 4th of that year, which is real cute for me, ‘cause I’m editing this episode exactly 39 years later. Warhol later recalled that Basquiat, quote, "went home and within two hours a painting was back, still wet, of him and me together."13 That painting, titled Dos Cabezas, ignited a friendship between them.

20:40 In December of 1982, Basquiat flew to California to work on some paintings for art dealer Larry Gagosian for an early 1983 show. He was accompanied by a beautiful girlfriend, a then-unknown singer who you might know today. Her name is Madonna. Gagosian later recalled, quote, "Everything was going along fine. Jean-Michel was making paintings, I was selling them, and we were having a lot of fun. But then one day Jean-Michel said, 'My girlfriend is coming to stay with me.' I was a little concerned-one too many eggs can spoil an omelet, you know? So I said, 'Well, what's she like?' And he said, 'Her name is Madonna and she's going to be huge.' I'll never forget that he said that."14 End quote. There are tons of photos of them together from this time, and it’s so surreal seeing Madonna so young. She’s almost camera-shy, even a little overshadowed by the people around her. It’s something else.

21:35 1983 was a huge year for Basquiat. While he was already quite famous in the art world, this is when his paintings started selling for a lot of money and when he started to become not just an art world darling but a well-known celebrity, like Warhol. Of course, he continued his interdisciplinary art practice. He produced the hip-hop record "Beat Bop" featuring Rammellzee and rapper K-Rob. It was pressed in limited quantities and Basquiat created the cover art for the single, making it highly desirable among both record and art collectors.

22:04 Meanwhile, he was also the youngest artist to ever participate in the Whitney Biennial, the longest-running survey of American art. It always features artwork that was created in the previous two years, and it’s a really significant stamp of approval from the establishment art world to be included.

22:18 In 1983, Bischofberger convinced Basquiat, Warhol, and a third artist, Francesco Clemente, to do a series of collaborative works together. Bischofberger was inspired by the Surrealist game of the exquisite corpse, where several different artists worked together on the same sheet of paper, folding it to hide their own contribution from the next person. When it is unfolded, the final work is revealed.15 Warhol and Basquiat became so close through this collaboration that in the summer of 1983 Basquiat actually moved into a studio-slash-apartment that Warhol owned in NoHo, to be closer to Warhol’s studio. So, the three worked together for several months, and afterward Warhol and Basquiat remained friends, establishing a relationship that has been obsessed over by the art world ever since. Artist Ronny Cutrone said, quote, “It was like some crazy art-world marriage and they were the odd couple. The relationship was symbiotic. Jean-Michel thought he needed Andy’s fame and Andy thought he needed Jean-Michel’s new blood. Jean-Michel gave Andy a rebellious image.”16 End quote.

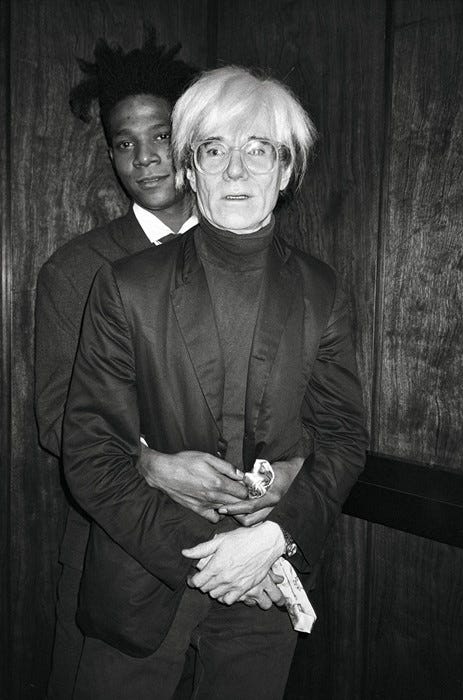

23:14 I don’t want to go too deep into Warhol, since eventually, I’ll probably do an episode all about him. But this was a huge part of Basquiat’s life--I mean, he had idolized Warhol as a child and then got to work with him, and how many of us get to do that? And yet there’s also a lot of big question marks next to their relationship, soooo, let’s talk about it. Their relationship was not strictly professional. I mean, I already mentioned that Basquiat moved into an apartment Warhol owned. They also spent a lot of their free time together: they got manicures together, they worked out together, they went to parties together. Normal friend stuff, in my opinion, but then there’s this part that’s not totally normal, at least from the outside looking in.

23:50 Warhol was always known to be awkward and somewhat voyeuristic. And he definitely embodied this with Basquiat. He was obsessed with Basquiat’s sex life, caring way more about that than his own sex life. (As a side note, Warhol once said, quote, “Sex is more exciting on the screen and between the pages than between the sheets,” end quote, which some use as evidence that he was asexual.17) Warhol wrote extensively in his diaries about Basquiat’s relationships. He documented his friend’s romantic life from 1983 on, often noting when he was in love, when he was dating several girls at once, and when he kissed Madonna in a club, even though they were no longer dating.18

24:28 The intensity of their relationship was questioned by people that knew the two of them well. Warhol even recalled in a diary entry that Basquiat’s girlfriend Paige Powell asked him, quote, “Are you starting up your gay affair again with Jean-Michel?” End quote. Warhol, maybe a little defensively, responded, “Listen, I wouldn’t go to bed with him because he’s so dirty.”19 End quote. And I just want to point out here that this could be construed as a racial slur, but it might be more about the fact that Jean-Michel rarely washed paint off of himself between work and play on a daily basis, and Warhol, by comparison, was very fastidious. That girlfriend I mentioned earlier, Suzanne Mallouk, later said of Warhol, quote, “Andy, like many people, was very seduced and enamoured by Jean-Michel.”20 This is hardly surprising, considering that Basquiat did seem to have some sort of strong charisma that attracted people to him. It is worth noting that Suzanne also described Basquiat’s sexuality as, quote, “Not monochromatic. It did not rely on visual stimulation, such as a pretty girl. It was a very rich multichromatic sexuality. He was attracted to people for all different reasons. They could be boys, girls, thin, fat, pretty, ugly. It was, I think, driven by intelligence. He was attracted to intelligence more than anything and to pain."21 End quote.

25:43 I think it’s unlikely that their relationship was romantic or sexual. Basquiat’s relationship with his father was bad, and I think it’s more likely that Basquiat saw Warhol as a mix of friend and father figure. He was known to take Warhol’s advice seriously. He worked harder and created more and was in more control of his drug use while they were friends. Warhol might have been something of a rock for him.

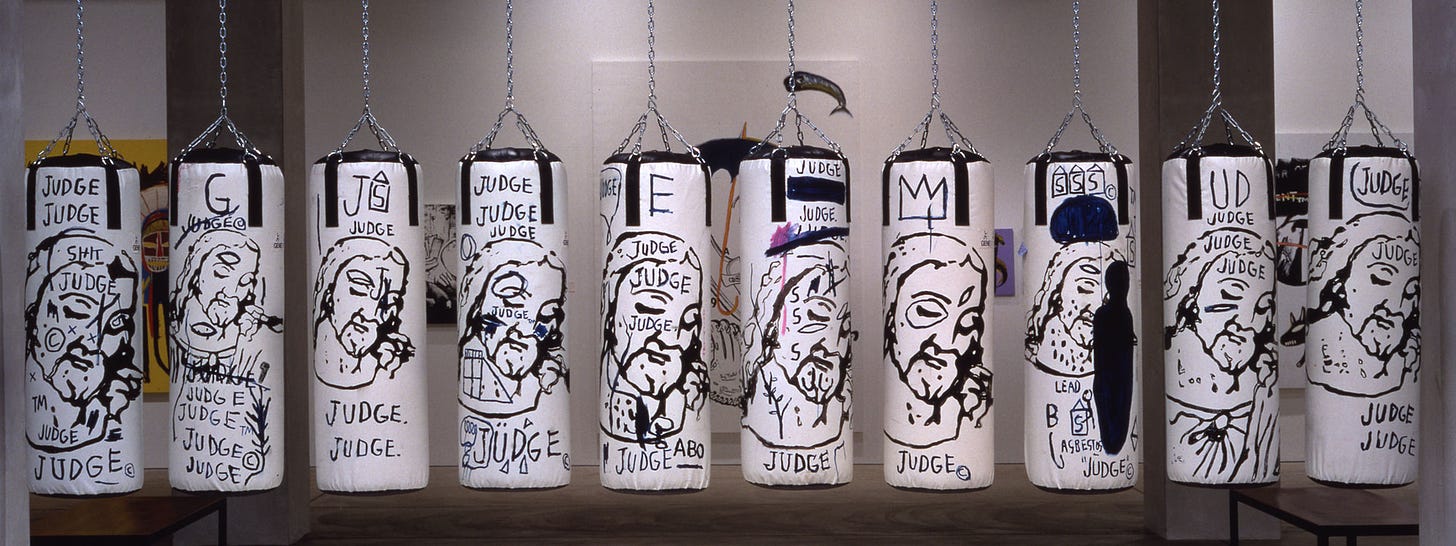

26:05 Whatever the nature of their relationship, they continued to work together until 1985. In that time, they made more than 150 collaborative works. Usually, Warhol would start with a fairly recognizable image, which Basquiat would then deface in some way. One of their most well known collaborative pieces is “Ten Punching Bags (Last Supper)” made around 1985, which was a playful statement against ideological oppression in the art world.22

26:30 Today, people love, I don’t know, a lot of these works, not all of them. But when they were first created, not everyone received these works very well. Many even outside the New York art scene saw Warhol as almost vampiric, sucking the life out of Basquiat’s art in order to benefit his own fame. Their joint exhibition, Paintings, in 1985, caused a rift in their friendship when it was largely panned by critics.

26:54 Basquiat, by this point wealthy, would often paint in Armani suits, and then go out to clubs at night still wearing his paint-splattered clothes. He was covered everywhere in the media, from GQ to MTV to a cover story in The New York Times. I mean, he had always been a bit of a partier--I mean, it was New York in the 1980s. But by the mid-1980s, things started to spiral a little. He was heavily using cocaine and heroin. In fact, he was using so much cocaine that in 1985 he blew a hole in his nasal septum, which is hard to do. The emotional instability that was probably a result of his childhood (apparently) haunted him. Journalist Michael Shnayerson once wrote, quote "The more money Basquiat made, the more paranoid and deeply involved with drugs he became.”23 End quote. A lot of his art world peers theorized that his drug use was a means of coping with the demands of his sudden fame, the exploitative nature of the art industry, and the pressures of being a Black artist in a White-dominated art world. I haven’t touched on the racism Basquiat faced yet, but it was… bad. I’ll get to that in a little while.

27:56 Now, I could list all the shows Basquiat was featured in from 1985 and on, but in some ways it’s not that interesting. He opened six shows in a single year, which is impressive for any artist, of course. I think it’s more interesting that almost every time a Basquiat work comes up for auction, it sets some kind of record. In 2017, his 1982 Untitled, which depicts a skull with a lot of red and yellow coloration, sold for 110 million dollars at Sotheby’s, which is the highest price ever paid for an American artist at auction.24 It’s also just fun to note that in 1987, Basquiat modeled in a Comme des Garçons show wearing a pale blue suit, black buckle shoes, white shirt and white bow tie. Look up the photos, it’s--it’s really cute.

28:38 In late 1986, his then-girlfriend Jennifer Goode successfully convinced Basquiat to get into a methadone program, but he quit after three weeks. In the last eighteen months of his life, he became increasingly reclusive, and after the death of Andy Warhol in February 1987 he really hid himself away, and some think his ongoing drug use was in part to cope with that grief.

29:00 In 1986 or 1987, Basquiat made an attempt to heal the rift he’d had with Al Diaz. In that interview with Dazed, Diaz said, “Jean showed up at my house and gave me a painting. It was a diptych and it said ‘To SAMO©, from SAMO©.’ I sold it like an idiot – and I felt really shitty about it. It's one of the things I regret in my life, one of the things I should have thought a little more about because it was made specifically for me. He made it just for me, and I was very callous like it didn't mean anything. I’ve tried looking for it and no one knows where it is.”25 They were never as close again as they had been in the late 1970s, and part of me wonders if Basquiat’s fame had him reminiscing about simpler days and trying to reach out to the people who had cared for him back then.

29:42 In early 1988, Basquiat was traveling a lot. He went to Paris and Dusseldorf for shows and befriended a few other artists. In June of that year, he took a trip to Maui, and when he returned he saw his friend Keith Haring. Basquiat happily reported to him that he’d finally kicked the drugs. Glenn O’Brien too reported that he’d seen Basquiat around this time and that Basquiat had said he was feeling really good.

30:03 And then, on August 12, 1988, he was found unresponsive in his bedroom by his girlfriend Kelle Inman. He was taken to the hospital but pronounced dead on arrival. He had died of a heroin overdose at just 27 years old.

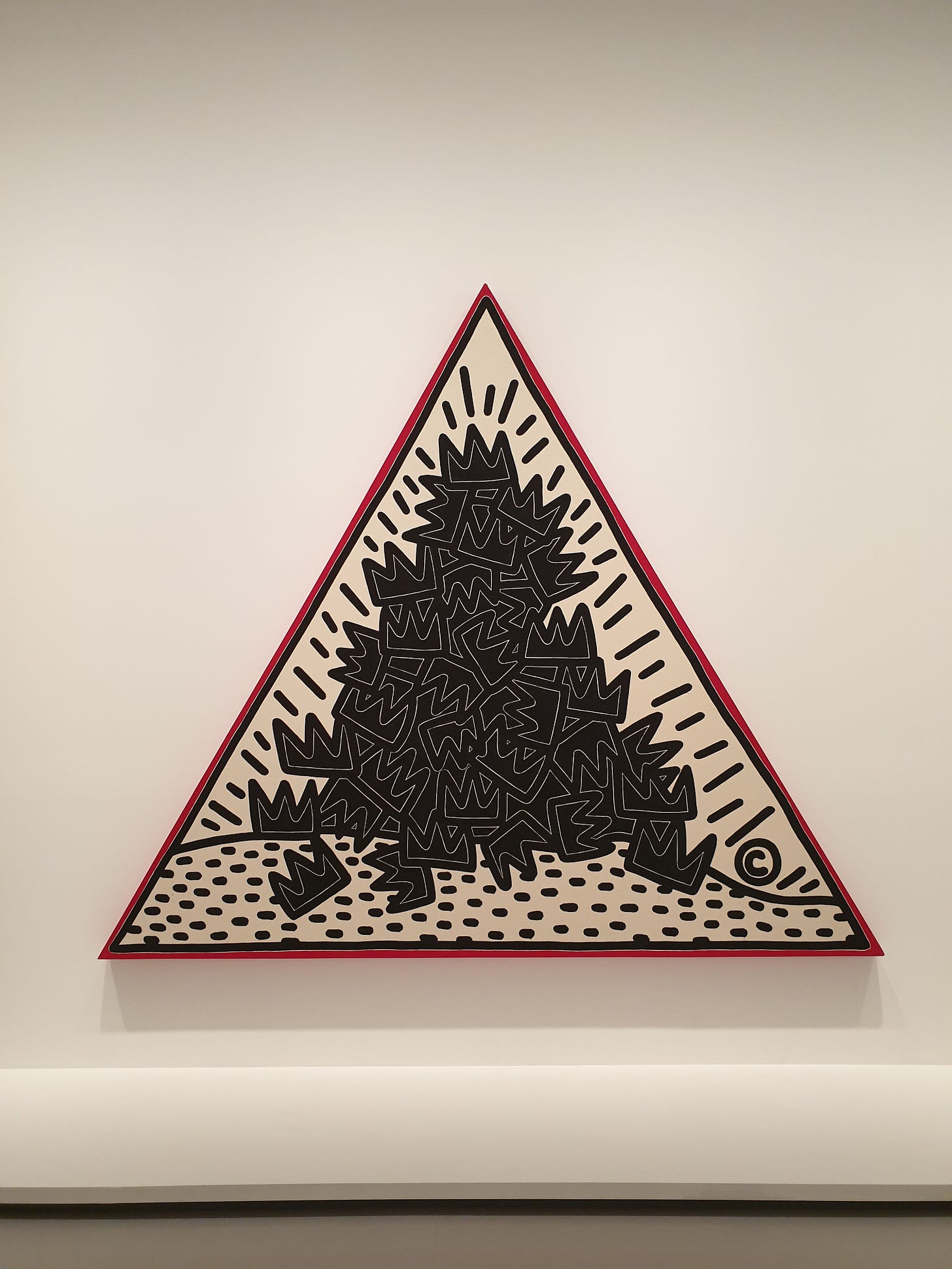

30:17 In the aftermath of his death, Keith Haring produced the painting A Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat, referencing how Basquiat had symbolically used the crowns in his own paintings.

20:27 Now, I didn’t want to end here, on a sad note, so let’s talk a little bit more about his art, how it’s understood, and why it’s becoming so famous again right now.

🖼️Understandings of his art

30:40 As I mentioned at the top, Basquiat is known as a Neo-Expressionist, an art style that was characterized by very introspective and subjective works, as well as a rougher approach to handling materials, as compared to the seamless and flat appearances of, say, Pop Art. It was a reaction against Conceptual art and Minimal art of the 1970s. After decades of abstraction and rejection of clear subjects or objects in art, the Neo-Expressionists were portraying recognizable objects, such as animals, objects, and the human body, in a rough and violently emotional way, often using really vivid, intense coloring.

31:16 Neo-Expressionism was also often referred to as ‘Wild Child’ art, which was definitely a reference to the quote “untamed” and “savage” end quote style of African art. Sometimes, it was seen as a renewal of Primitivism, a style of art that had idealized non-Western cultures and saw, quote, “primitive people” end quote, as inherently more noble than people living in developed countries. And it was based on a philosophy that some past state of nature was more ideal than our modern state of existence. Both ‘Wild Child’ and ‘Primitivism’ are very much kind of white supremacist terms, even though probably they weren’t meant that way, but it’s clearly what has prompted them. They idealize what people of color and their cultures are “supposed to” be like. While some famous establishment artists like Picasso experimented with Primitivism, most understandings of it try to celebrate quote “unschooled” end quote art while also separating out those artists as being “unschooled” and quote, “not traditionally trained.” For artists of color, it was a subcategory that they could be relegated to, meant to say something like, quote, “This is acceptable Black art.” Or, more commonly, “We like this ‘primitive and savage’ art… when it’s painted by white people.” Because not everyone painting in the Neo-Expressionist style was Black, nor were they all subject to this criticism. But Basquiat, as a young Black artist, got called ‘the Wild Child’ of the art world.

32:39 Now, I was gonna rewrite this myself, but the way Maddox Gallery in London summed this up is better than anything I could do26, so I’m just going to quote them whole cloth, but I’m warning you because it’s a long quote:

Basquiat's art focused on dichotomies such as wealth versus poverty, integration versus segregation, and inner versus outer experience. He appropriated poetry, drawing, and painting, and married text and image, abstraction, figuration, and historical information mixed with contemporary critique. He used social commentary in his paintings as a tool for introspection and for identifying with his experiences in the Black community of his time, as well as attacks on power structures and systems of racism. Basquiat's visual poetics were acutely political and direct in their criticism of colonialism and support for class struggle.

33:22 End quote. Because Basquiat was an artist who consumed culture, quote, “voraciously” and recycled everything that he found relevant into the over 2000 paintings, drawings, and objects he created, as well as music and performance.27 He sampled from the world around him; Buchhart compared him to artist and composer John Cage, who brought chance elements from everyday life into his works.

33:43 As for what he was like while he was actually painting... Well, the way he moved was described as dance-like and harmonious. No surprise, for someone who was musically inclined, but people certainly ascribe a certain amount of romance and sexuality to this. His studio space was often chaos--televisions would be playing while music was playing while people were over--it was not a tranquil space, he was constantly listening to other things and using what he heard and read and learned in his work.

34:09 Annina Nosei, the gallerist who had given Basquiat supplies and space to get started, described28 how he drove her crazy with the incessant noise from his basement studio:

He drove me crazy with the Bolero of Ravel. Bolero drove me crazy because he had it downstairs, underneath me, this record—not a record player—a boom box. I would say, “Please, Jean-Michel, change the music!”

34:28 In addition to Gray’s Anatomy, Basquiat read French symbolist poetry at a young age, which would show back up in his art later on. The Symbolists were a group of French writers in the late 19th century who favored dreams, visions, and imagination in their poetry. They rejected tendencies toward naturalism and realism, believing that the whole purpose of art was not to recreate reality but to actually access greater truths through the, quote, “systematic derangement of the senses,” as poet Rimbaud described it.29 You can see a lot of this in the way Basquiat simultaneously depicts the inner world and outer appearance of people.

35:04 His consumption of so much material allowed him to hide some of his real personality behind everything he created. And as Jane Alison points out in her forward to Basquiat: Boom For Real, quote, “all of this action tends to obscure an artist of fierce intelligence, poetic sensibility, and profound depth.”30

35:20 Now, sampling so much work in this fashion, especially with his attitude that was kind of like copy-and-paste, he opened new ways of thinking about his subjects. He brought things together that normally were kept apart. Curator Lydia Yee once said, quote, “Like a DJ, he adeptly reworked Neo-Expressionism’s cliched language of gesture, freedom, and angst and redacted Pop Art’s strategy of appropriation to produce a body of work that at times celebrated Black culture and history but also revealed its complexity and contradictions.”31 He positioned himself against political apathy with his work, fighting against exploitation, consumerism, oppression, racism, and police brutality with each brushstroke.

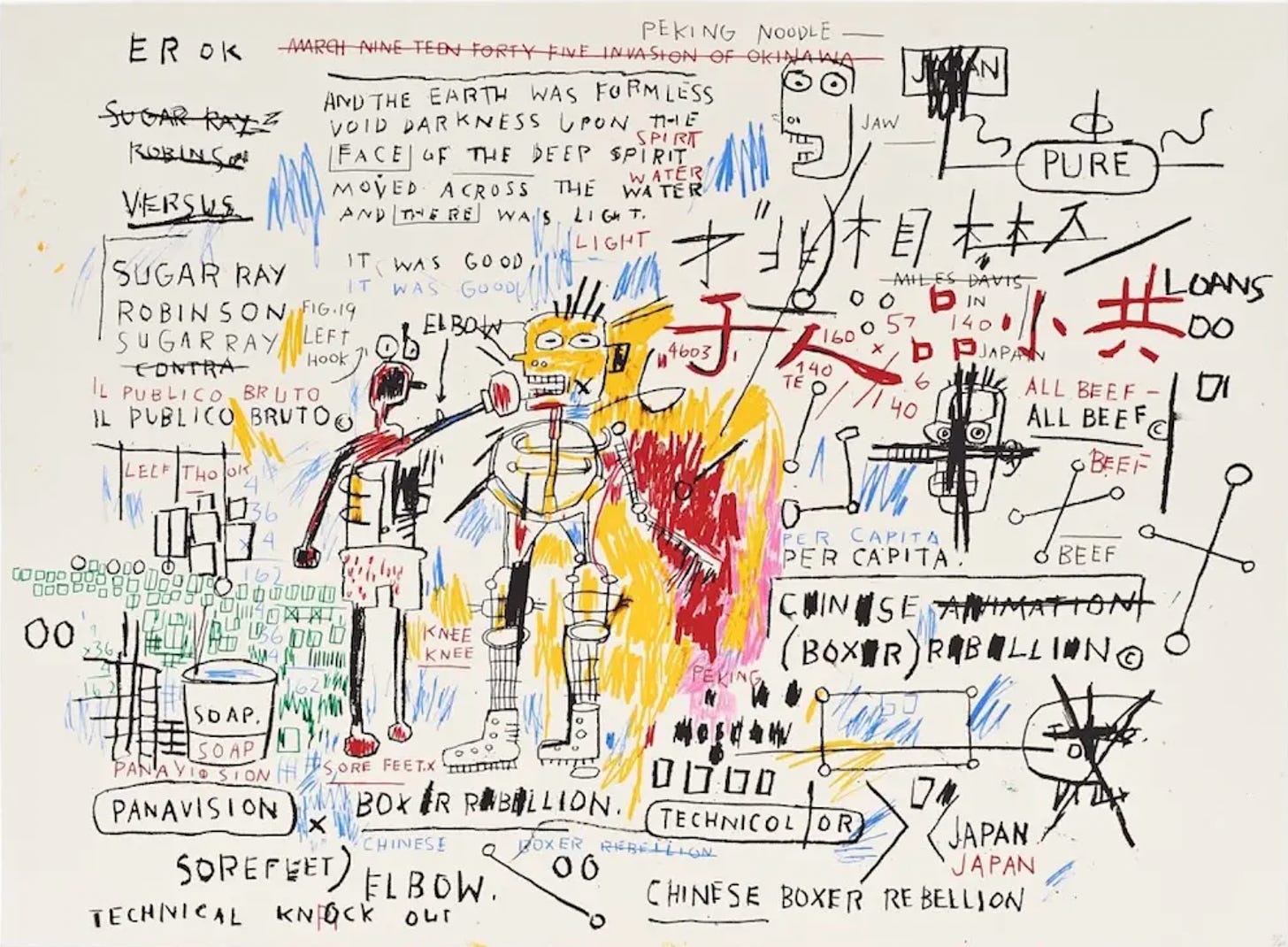

35:59 A lot of people, everyday consumers and art lovers alike latched onto the quote “exoticism” of Basquiat’s work, especially in paintings like his 1983 Boxer Rebellion, which featured bright colors and stick-figure-like characters fighting. They liked the symbols in Mandarin splashed across it, and all the words like brushstrokes that make up the work. But the work itself is a commentary on how people of color in America, especially Black people, used to only be able to hope to rise in class through things like boxing or acting. This was the only time that a Black man in America could really “win” quote/unquote over a white person. The painting, Boxer Rebellion, is covered in references to racism, to class issues, as a way of expressing what Basquiat himself was facing and what he was watching others around him go through.

46:44 There’s an interview with Art New York that Basquiat gave in 1983 that I think is really emblematic of the racism he faced every day. I’m going to link to it in the show notes because while it is cool to see Basquiat talking about his own art, I think it’s also really important, especially for other white folks out there, to see what I’m talking about. The interviewer’s questions are so condescending and Basquiat is clearly uncomfortable around him. The video even starts with, quote, “After much coaxing, Jean-Michel reluctantly agreed to let Art New York interview him in the Spring of 1983 in his loft on Crosby Street.”32 ‘Reluctantly!’ Like, he did not want them there! I can only imagine what constituted the ‘coaxing’ they had to do to be allowed into his home. Then for the interviewer to imply that Basquiat can’t actually read… Ugh. I think there are longer versions of this same clip out there, but this 3-minute clip is enough.

37:34 So, Basquiat had several repeating motifs and phrases that became like signatures for him. The phrase, “Boom For Real” for one. He used it as an expression, and an artistic strategy. In a documentary on Basquiat, Diego Corte noted the expression’s relationship to explosions, and said, quote, “You end up with fragments rather than the Cubist and post-Cubist way of building sections, hatching things together… Jean-Michel’s work was not about a quilt, it was about a galaxy of reality that has been again exploded. So everything is equal.”33

38:04 The three-point crown, which he put over the heads of people and ideas he respected, was a huge symbol for Basquiat; so big, in fact, that it is Haring’s entire homage to him. All the way in 1981, it was already so part of his body of work that it was considered his in many ways. In his “The Radiant Child” article for Artforum, Rene Ricard asked Basquiat about it (and this is kind of a long quote as well):

I asked Jean-Michel where he got the crown. “Everybody does crowns.” Yet the crown sits securely on the head of Jean-Michel’s repertory so that it is of no importance where he got it bought it stole it; it’s his. He won that crown. In one painting there is even a copyright with a date in impossible Roman numerals directly under the crown. We can now say he copyrighted the crown. He is also addicted to the copyright sign itself. Double copyright. So the invention isn’t important; it’s the patent, the transition from the public sector to the private, the monopolizing personal usurpation of a public utility of prior art; no matter who owned it before, you own it now.

39:01 End quote. Though he achieved huge fame and success in his lifetime, in many ways Basquiat is more well-known today. In a conversation at Maddox Gallery in March 2020, Maeve Doyle, a curator and artistic director, talked about how Basquiat himself was in some ways ahead of his time. He was an activist, talking about themes of racial inequality in America in ways that a lot of Americans are only just starting to listen to and understand. Not to say that no one else was talking about this in the 1980s, just that now people are listening more and his voice seems louder.

39:32 Annina Nosei saw this early on--it was Basquiat’s conviction in his sociopolitical beliefs and in his ability to translate that into art, that convinced Nosei to front him the money for canvases and paint. This is also a long quote, and I’m sorry about that, but I think it’s important to include in full, because she knew him for so long and saw this transition of his beliefs. So the quote34 goes:

He lost a little bit of [the strong sociopolitical aspect to his work] later on, because he was confused by the amount of money and attention. He had a better sense of purpose at the very beginning. His revolutionary aspect was much stronger at the beginning than the end. He had very clear thoughts that were not very flattering about certain people in the art world. But then later, he would accept their money.

I would let it be. I think he was upset and felt as though he had betrayed himself sometimes, and I think that some of the reasons for the drugs had to do with the fact that he was too deeply offended by the stupidity of the art world. When he first entered the art world he had great enthusiasm, and as he started to make money, he said that he wanted to create jobs for other people. I remember he wanted to have a record company. He liked that idea.

40:34 End quote. Concurrent to his disenchantment with the art world as his fame grew was a growing disenchantment with the world in general that probably a lot of people go through in their twenties. I didn’t mention it earlier, but there was a police-involved death in New York in 1983 that sounds devastatingly familiar to the deaths of Black Americans like George Floyd. Michael Stewart was a graffiti artist who Basquiat knew well from his time working as SAMO. Early on September 15, 1983, several white Port Authority officers arrested Stewart for allegedly tagging a subway car. During the violent encounter, Stewart was severely injured, and he died two weeks later. What exactly happened during the arrest remains unsettled. As you can probably guess, a grand jury failed to indict the officers on charges of criminally negligent homicide. However, a civil settlement was later awarded to the Stewart family.

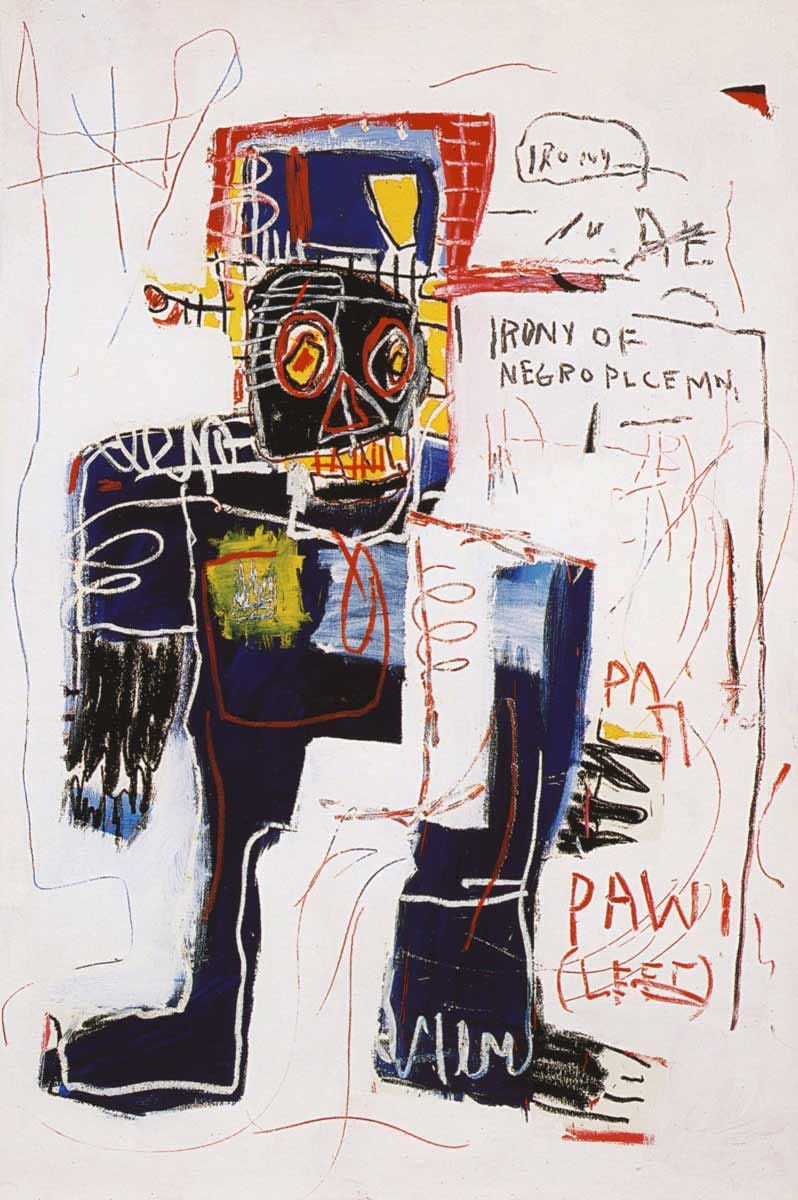

41:22 This needless death drew New York City to the verge of civil unrest. After Stewart’s death, Basquiat was deeply impacted by it and was often heard telling his friends, quote, “It could have been me.”35 He painted Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart) in 1983 in response. Basquiat also participated in a Christmas benefit that year with various New York artists for the family of Michael Stewart. He had already painted Irony of Negro Policeman in 1981, as a commentary on the way the predominantly white police force of New York used violence to control the minority populations. At this point though, the painful irony took on a sharper note. It seems even more prescient now.

41:59 It’s because his work is so relevant that Basquiat’s legacy looms large over the art world. When people try to say that racism or police brutality are new problems or invented problems, we can point to people like Basquiat to show that this has been an issue for much longer than just the last couple years.

42:15 Basquiat became one of the most famous artists of the 1980s, which was no small feat for a Black artist in the US. It was nearly unheard of, in fact, for a Black artist to be so celebrated by the establishment art world, which was so predominantly white. And he made it possible for other Black artists to follow in his footsteps, gaining acclaim and wealth through traditional art establishment channels. He remains one of the most well-known American artists, inspiring artists and musicians for decades. It’s hard not to wonder what else he would have created, had he had more time, but I suspect we’ll spend decades more unraveling the many layers of meaning he left us in the works he already created.

42:51 I hope you liked this episode of Unruly Figures. Basquiat’s story is both inspiring and tragic, in a dichotomy that maybe even he himself would have appreciated. There’s so much more that I could cover, but, you know, it’s early days and I didn’t want to start with two-hour episodes right out of the gate.

📚Bibliography

Books

Buchhart, Dieter, et al. Basquiat: Boom for Real. Barbican, 2017.

Miller, Harland, and A. S. Byatt. “Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Writers on Artists, Published in the United States by DK Publishing, Inc., New York, 2001, pp. 290–295.

Saggese, Jordana Moore. Reading Basquiat: Exploring Ambivalence in American Art. University of California Press, 2021.

Schad, Ed. 50 Artists: Highlights of the Broad Collection. The Broad, 2020.

Websites

AnOther. “Ten Things You Might Not Know about Basquiat.” AnOther, 7 July 2015, https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/7569/ten-things-you-might-not-know-about-basquiat.

“Armani Suits and Bare Feet: How Jean-Michel Basquiat Created His Look.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 12 Sept. 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2017/sep/12/armani-suits-and-bare-feet-how-jean-michel-basquiat-created-his-look.

Dazed. “The Best, Worst, and Weirdest Parts of Warhol and Basquiat's Friendship.” Dazed, 28 May 2019, https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/44600/1/never-before-seen-photos-diary-andy-warhol-jean-michel-basquiat-friendship.

Dazed. “The Story of Samo©, Basquiat's First Art Project.” Dazed, 6 Sept. 2017, https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/37058/1/al-diaz-on-samo-and-basquiat.

Deitch, Jeffrey. “An Interview with Annina Nosei.” The Jean-Michel Basquiat Tribute, http://www.basquiat.cloud/annina-nosei-memories-basquiat/.

“Exquisite Corpse: Moma.” The Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/exquisite-corpse.

Interview. Brant, Peter M., and Larry Gagosian. “Larry Gagosian.” Interview Magazine, 3 Jan. 2013, https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/larry-gagosian.

“Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 5 Oct. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Michel_Basquiat#Anatomy_and_heads.

“Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 5 Oct. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Michel_Basquiat#Gallery_artist:_1980%E2%80%931985.

Klein, Barbara. “Art, Friendship, and an Awakening - Carnegie Magazine.” Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, 8 June 2021, https://carnegiemuseums.org/carnegie-magazine/spring-2021/art-friendship-and-an-awakening/.

“Paul Tschinkel's New York New Wave at P.S. 1 The Armory Show of the 80s.” Howl! Arts, 30 May 2018, https://www.howlarts.org/event/new-york-new-wave-at-p-s-1-the-armory-show-of-the-80s/.

“Race, Power, Money: A Conversation about Basquiat.” Maddox Gallery, https://maddoxgallery.com/news/48-race-power-money-a-conversation-about-basquiat/.

Ricard, Rene. “The Radiant Child by Rene Ricard, Published in Artforum.” Judy Rifka, Judy Rifka, Dec. 1981, https://www.judyrifka.com/texts/2017/10/10/the-radiant-child-by-rene-ricard-published-in-artforum-1981.

Shnayerson, Michael. “How Contemporary Art Became a Fiat Currency for the World's Richest.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 16 May 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-16/boom-review-michael-shnayerson-chronicles-contemporary-art-rise.

“Symbolist Movement.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/learn/glossary-terms/symbolist-movement.

“Untitled (1982) Painting.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 1 Oct. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Untitled_(1982_painting).

YouTube. “Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) by Paul Tschinkel.” YouTube, YouTube, 2 July 2010, youtube .com/watch?v=Z2ytkFDzdbk&ab_channel=PaulTschinkel

AnOther. “Ten Things You Might Not Know about Basquiat.” AnOther, 7 July 2015, https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/7569/ten-things-you-might-not-know-about-basquiat.

Dazed. “The Story of Samo©, Basquiat's First Art Project.” Dazed, 6 Sept. 2017, https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/37058/1/al-diaz-on-samo-and-basquiat.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Paul Tschinkel's New York New Wave at P.S. 1 The Armory Show of the 80s.” Howl! Arts, 30 May 2018, https://www.howlarts.org/event/new-york-new-wave-at-p-s-1-the-armory-show-of-the-80s/.

Buchhart, Dieter, et al. Basquiat: Boom for Real. Barbican, 2017.

“Armani Suits and Bare Feet: How Jean-Michel Basquiat Created His Look.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 12 Sept. 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2017/sep/12/armani-suits-and-bare-feet-how-jean-michel-basquiat-created-his-look.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Deitch, Jeffrey. “An Interview with Annina Nosei.” The Jean-Michel Basquiat Tribute, http://www.basquiat.cloud/annina-nosei-memories-basquiat/.

“Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 5 Oct. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Michel_Basquiat#Anatomy_and_heads.

Miller, Harland, and A. S. Byatt. “Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Writers on Artists, Published in the United States by DK Publishing, Inc., New York, 2001, pp. 290–295.

Dazed. “The Best, Worst, and Weirdest Parts of Warhol and Basquiat's Friendship.” Dazed, 28 May 2019, https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/44600/1/never-before-seen-photos-diary-andy-warhol-jean-michel-basquiat-friendship.

Interview. Brant, Peter M., and Larry Gagosian. “Larry Gagosian.” Interview Magazine, 3 Jan. 2013, https://www.interviewmagazine.com/art/larry-gagosian.

“Exquisite Corpse: Moma.” The Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/exquisite-corpse.

Dazed, May 2019.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 5 Oct. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Michel_Basquiat#Gallery_artist:_1980%E2%80%931985.

Dazed, May 2019.

Shnayerson, Michael. “How Contemporary Art Became a Fiat Currency for the World's Richest.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 16 May 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-16/boom-review-michael-shnayerson-chronicles-contemporary-art-rise.

“Untitled (1982) Painting.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 1 Oct. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Untitled_(1982_painting).

Dazed, September 2017.

“Race, Power, Money: A Conversation about Basquiat.” Maddox Gallery, https://maddoxgallery.com/news/48-race-power-money-a-conversation-about-basquiat/.

Jane Allison, Basquiat: Boom for Real.

Deitch.

“Symbolist Movement.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/learn/glossary-terms/symbolist-movement.

Allison, 6.

Buchhart, 19.

YouTube. “Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) by Paul Tschinkel.” YouTube, YouTube, 2 July 2010, youtube .com/watch?v=Z2ytkFDzdbk&ab_channel=PaulTschinkel

Buchhart, 19.

Deitch.

Klein, Barbara. “Art, Friendship, and an Awakening - Carnegie Magazine.” Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, 8 June 2021, https://carnegiemuseums.org/carnegie-magazine/spring-2021/art-friendship-and-an-awakening/.