August Landmesser: Transcript, Bibliography, and Photos

Thanks for checking out Unruly Figures! I’m able to keep these transcripts, bibliographies, and more free because of the amazing people who help support this work. Want to support independent and in-depth research? Subscribe now!

Before I hop into today’s transcript, I wanted to make sure you’re all aware of a new project from Substack called Substack Go. If you participated in Substack Grow (or wish you could have) make sure that you apply for Go. From the announcement:

The Substack team will connect Go participants to a small squad of eight to ten fellow writers in the same category or region for four weeks of support and structured guidance through the month of February.

Writers will leave the program with an understanding of Substack fundamentals, a squad of peers to turn to, and an established writing and publishing cadence.

Substack is built on the belief that to properly support independent writers we have to do more than just build software—we have to create the infrastructure to support writers in everything they do, from helping with health insurance to providing structured opportunities to connect and learn.

If you’ve set a New Year's resolution to go deeper into your writing practice, or to kickstart a new one, you don’t have to go at it alone. We hope you will join us for Substack Go.

I’ve already applied—maybe we can hang out in a small group and become better writers together! Learn more about Substack Go and apply here.

Today I’ve got the transcript and bibliography for Unruly Figures episode 9, August Landmesser. At the beginning of each paragraph is a time code for where you can find that in the episode. I also do endnotes throughout, in case you want to follow up with a resource for more reading!

🎙️ Transcript

Here’s the episode:

You can also listen to Unruly Figures on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and wherever you get your podcasts.

0:05 Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m going to be covering a man you may have never heard of: August Landmesser.

0:19 He grew up in Germany in the early 20th century, so you can probably guess that we’re dealing with World War II and the Holocaust. Landmesser was against these ideas, and today we’re going to talk about how he rebelled against the Nazis.

0:32 Real quick, before we get started, I want to thank Peter for suggesting August Landmesser to me. If you would like to suggest someone to cover, you can do that by logging onto the Unruly Figures Substack page and leaving a comment in the suggestion box. That’s U-N-R-U-L-Y-F-I-G-U-R-E-S dot S-U-B-S-T-A-C-K dot com. In addition to the suggestion box, you can also get a full transcript, ad-free episodes, a bibliography of my research, photos of everyone I’m covering, discussion threads, and so much more. So check it out!

1:06 All right, let’s hop back in time.

1:08 For my coverage today, I relied a lot on August’s daughter’s book about political persecution in the Third Reich. It was originally written in German, but the English translation by Jean Macfarlane is called A Family Torn Apart by “Rassenshande.” The book is hard to come by (uhm, I wanted to do this episode back in November but I had to order the book from Germany, thus forcing the date of this to be pushed back), but if you can find it, it’s a fantastic resource for anyone studying the political policies of the Third Reich. It’s full of original scans of government documents and reports from Hamburg, Germany that date to the 1930s and 1940s. If that’s an area of interest for you, search for Irene Eckler’s book.

1:48 August Landmesser was born on May 24, 1910 in a city called Moorege, which is north of Hamburg, in Germany.1 Unfortunately, we don’t know much about his early life, though we know he was an only child. His father was named August as well, and his mother was named Wilhelmine Magdalene (née Schmidtpott).2 According to Rudolf Landmesser, whose relation to August is unexplained (maybe a distant nephew?) August was, quote, “Coddled by his unassuming mother.”3

2:15 Rudolf also described August as intelligent, saying that he, quote, “sailed through the elementary school in Moorrege.”4 He continued, “I’d describe him as a country lad who, had he been given more opportunities at home, could certainly have made more of himself.”5

2:30 You see, after World War I Germany’s economy was destroyed. The Treaty of Versailles had not only blamed Germany solely for the war, but forced Germany to pay 132 billion gold marks in restitution, which was equal to about 269 billion US dollars back in 2019.6 But Germany had suspended the gold standard to finance the war, and so hyperinflation really took off in the face of this crushing debt. “By November 1923, 42 billion marks were worth the equivalent of one American cent.”7 ONE! CENT!

3:08 So, this blow to both German national pride and the economy certainly fed the Nazi party and Hitler’s rise 20 years later. And I hope it makes it a little bit understandable that Landmesser, when he was just 21-years-old, joined the Nazi party. By 1931 when he did this, registered members of the party received preference in hiring for certain posts, and he really needed a job. For better or worse, there’s not a lot of proof that this decision helped him at all though.

3:34 Landmesser was kicked out of the party just four years later, in 1935, for falling in love with a Jewish woman named Irma Eckler.

3:43 Irma and August met in October 1934 and were probably engaged to be married by the 21st of April, 1935, according to what I think is an engagement announcement that was included in Eckler’s book. I don’t speak a word of German, so I had to translate it using Google, so I’m not 100% sure of what I’m looking at, but the date is definitely April 1935. There’s some dispute about what happened next: They either married first in a private ceremony and then tried to register it with the government, or they tried to register their marriage first. Either way, when they went to register their marriage in Hamburg in August 1935, they were denied based on a law that hadn’t actually gone into effect yet.8 The so-called Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor was an anti-miscegenation law. That is, it outlawed romantic relationships between Jewish people and Aryan Germans, but it wasn’t supposed to actually come into effect until September 15th, 1935. The government’s refusal to acknowledge their marriage is probably due to the language of the law. Here’s a quote from that section:

Marriages between Jews and subjects of German or kindred blood are forbidden. Marriages nevertheless concluded are invalid, even if they are concluded abroad to circumvent this law.9

4:58 End quote. So, as you can see, even if they had been allowed to marry in August 1935, it would be declared invalid a month later.

5:07 Let’s go over a little background on Irma: She was the youngest daughter of Friederike Sophie Eckler née Horneburg, who was a descendant of Sephardic Jews that had been forced to leave the Iberian Peninsula in the 15th century and had moved to Germany.10 Friederike married Arthur Eckler in 1905 and Irma was born in Hamburg on June 12th, 1913.11

5:29 I want to note some confusing dates that are coming up here–the writer, Irene Eckler (Irma’s daughter) says that Irma’s sisters were more than 10 years older than Irma, implying that Arthur is perhaps not the father of Irma’s sisters. It doesn’t totally matter for our story about August and his family, except that Irma’s sisters went on to survive WWII and were never taken to a concentration camp, but Irma was. And the identity of her father impacted the reality of the lives of Irma’s children. The author Irene suggests that the sisters avoided persecution because they both married Aryan Germans, but that doesn’t make a lot of sense to me because those marriages would have been invalidated under the same law that invalidated Irma’s marriage.12 Moreover, the Nazis were more than happy to split up families if it meant that German children weren’t, quote, “influenced” by a Jewish parent. What might have saved the older sisters though was if they could prove that they were not 100% Jewish, meaning their father was someone other than Arthur Eckler.

6:28 By the way, I realize this kind of talk is distasteful. It’s the Nazis. They classified people along what we might think of as really gross lines. They were obsessed with calculating a person’s exact percentage of Jewish ancestry and developing laws about who could marry who based on that percentage. Those classifications became hugely important in the everyday lives of people living under Third Reich law, as I’ll cover in more depth a little later. So yes, I realize that it’s uncomfortable, but the story is hard to tell without understanding where the main characters are coming from.

7:00 Now, in 1931, Frau Eckler and her daughters were baptized as Protestants and evidence suggests that she discontinued contact with Jewish community of Hamburg until 1949; The author, Irene, asks a lot of questions about this conversion, but we don’t have a lot of answers.13 It’s unknown whether it was because they hoped that as Christians they could avoid persecution. What is documented is that Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers’ Party was gaining power by 1931. Anti-Semitic incidents were also on the rise around Hamburg, and people were growing afraid of the possibilities of pogroms.14

7:35 Additionally, Frau Eckler had separated from and divorced Arthur by this point. She remarried a Christian man named Ernst Graumann in March of 1932, so the religious conversion could have been related to their impending nuptials.15 Frau Eckler would also manage to survive the Third Reich.

7:51 All right, back to our main story. We don’t know exactly how Irma and August met in 1934. We know that they were pretty serious about each other–their plans to wed having already been covered. Their first child together, a girl named Ingrid, was born on October 29th, 1935. Just judging by the dates, it’s possible that August and Irma decided to get married after realizing Irma was pregnant in April. To give birth in October, she would have gotten pregnant sometime around January, and they got engaged in mid-April. Irma probably would have realized by then that she was pregnant. But I don’t want that to stand in the way of understanding their relationship. They remained together for a long time, and were evidently very much in love.

8:32 Of course, Ingrid was considered an illegitimate child because her parents could not marry. August acknowledged paternity however, and the two had her baptized as Protestant.

8:40 On June 12th, 1937 the family celebrated Irma’s 24th birthday. She was pregnant with their second child by then.

8:48 On the same day, the Head of Security Police gave a secret directive internally that all Jewish women in unapproved relationships, like Irma’s with August, would be arrested. The edict says, quote, “In the case of ‘Rassenschande’ between a German male and a Jewish female, she is to be taken into Protective Custody immediately after legal proceedings have been completed.”16 Of course, as Irene Eckler points out in her book, this term ‘protective custody’ is very misleading–it wasn’t “protective” at all, it was criminal imprisonment.17

9:19 It was probably phrased this way because, surprisingly, it went against Hitler’s preferred way of dealing with this. Eckler’s book leaves a lot to be desired in terms of citation, but she seems to quote from another internal Third Reich document from 1937, which says that usually, quote,

‘Only the man could be punished for ‘Rassenschande.’’ However the woman was also threatened with prosecution for perjury or aiding and abetting if she tried to protect her partner. The culpability of women, who Hitler considered as always being the ‘passive partner’ in sexual matters, was not abolished until Hitler’s intervening decree of 16th February 1940. For years the Reich Ministry of Justice had been ignoring his instruction that women were not to be punished.18

10:01 Not to discredit the author’s effort or anything, it’s just that the book Eckler wrote reads a lot like compiled notes instead of a narrative or research publication, so I’m not quite sure what part of what I just read is quotations from the Third Reich law and what part is Eckler’s thoughts. But some other research I did supports this idea that Jewish women were being punished against Hitler’s wishes for these relationships.

10:24 Now, August and Irma didn’t hide their relationship. They were very proud of their love for one another and their child. However, that also meant it attracted the attention of the SS. In July 1937, perhaps feeling the pressure of their illegal relationship, August tried to secretly move to Denmark. His plan was to get a job there and send money home so that Irma and the children could join him later. However, he was arrested on July 28th, 1937. I’m not sure exactly what grounds he was arrested on–it may be because the government had already identified him as being in a relationship with a Jewish woman. It might have been because immigration without permission was illegal. We don’t know, though a letter I’m about to quote hints toward the second charge that I mentioned.

11:05 From prison, on August 3rd, Landmesser put in a plea for clemency, which was denied. In his plea, he calls Irma his “fiancée” and says that she’s, quote,

“expecting our second child any time now… I would like to marry her before this occurs and not leave her alone with the two children. I also ask that it be taken into consideration that I have never done wrong and that in this case the crime was committed thoughtlessly and, as it were, in a state of mental confusion, first due to the constant questions of acquaintances about how I’m going to manage any pay for everything once the second child arrives.”19

11:37 End quote. To me, that focus on pressure and money says what he was being punished for was trying to leave Germany without permission, not his relationship with Irma. At least at this point.

11:49 He also tried to get a, quote, “permit to marry a Jewess,” end quote, from the head of the government in Berlin, which was also denied.20 A few days later, on August 6th, his second daughter and the author I’ve been quoting, Irene, was born.

12:02 At some point between his August 3rd plea for clemency and mid-September, August was released from prison. We know this because a warrant for his arrest was put out on September 15th, 1937. This time, he was charged with ‘Rassenschande.’ I’ve said that word a few times–it translates literally to “racial disgrace,” but was used to imply quote-unquote “tainting” pure German blood.21 Which is obviously just [groans] a really, I don’t know, gross and uncomfortable thing.

12:30 I want to point out here that August Landmesser’s relation Rudolf had said the Landmessers had Jewish ancestors. He had traced the family back to a woman named “Susanna Remus, née Abraham,” who quote “came from the Tucheler Heide” area, or West Prussia.22 However, when August was tried for his relationship with Irma, the District Court in October 1938 ruled, quote, “The names (Landmesser, Schmidtpott, Remus, and Bester) are German. Foreign blood is not apparent. The accused also has an Aryan appearance.” August was light-skinned, blonde-haired and possibly blue-eyed, though photos of him only exist in black and white. It’s this classification that ensures his punishment. Had Landmesser been proven to have Jewish heritage, the whole quote-unquote “crime” goes away and we wouldn’t be talking about him today.

13:19 In a German newspaper in a little over a year later, August’s story was told as a warning to everyone else:

Aryan commits ‘Rassenschnade.’

Due to a particularly serious and grave offence against the Blood Protection Law, the 28 year old August Landmesser was called to account… For years, Landmesser had been having an affair with a Jewish girl with whom he fathered two children. Because the relationship was not even ended after the promulgation of the Nuremberg Laws, Landmesser was arrested in the summer of 1937 but acquitted after ten months detention, in May 1938, on the grounds of subjectivity. On this occasion he was strongly warned against his relationship… and was clearly told that in the event of a repetition of the crime he could expect a sentence of several years imprisonment. Nevertheless, Landmesser soon resumed his relationship with the woman.23

14:07 End quote. The acquittal based on “subjectivity” is based on his testimony that he did not know Irma was fully Jewish, but had presumed she was only Jewish on her mother’s side. He would have only known her step-father Ernst Graumann, so there’s maybe some truth to this. There’s also some evidence that Irma also didn’t know she was classified by the government as fully Jewish because she believed her paternal grandfather to be Aryan.

14:31 As soon as he was released, August went to the Graumanns’ home to see his children and reunite with Irma. The only photo ever taken of the family of four together was taken on this reunion. It’s included in the book and I’m going to try to include it in the Substack. It’s a really sweet photo of the family at a creek enjoying the water, the parents holding the two children.

14:50 The couple continued to appear together in public, refusing to follow the Third Reich laws.

14:55 Then, on July 15th, 1938, just a few months after he was released, August Landmesser was arrested again. He, quote, “blamed his relapse” on concern for his children, who he, quote, “feared to lose if he broke off the relationship [with Irma] completely.”24 End quote. This is probably crap, it seems like the couple was happy together. Uhm, but I don’t blame him for trying to get out of being punished under the law. As far as I can tell, he was the family’s only financial provider and was probably worried about what would happen to his children if he was convicted.

15:28 Nevertheless, he was sentenced to two and a half years of penal servitude for Rassenschande. The prosecutor had said that, quote, “‘Rassenschande’ by a true-blooded German male was to be regarded as a breach of trust with his…racial community.”25 End quote.

15:41 On July 18th, 1938, just three days after August was arrested, Irma was picked up by the Gestapo, the Secret State Police. She was also charged with Rassenschande. There’s no actual record of her arrest, either because it was done by the Gestapo or because it was still technically illegal to punish the women involved in these relationships. However, research done by her daughter shows that Irma was held in a police cell from July 18th through the 29th, 1938, then in the City of Hamburg’s prison from the 20th to 23rd of October of 1938.26

16:13 The children were sent to the municipal orphanage. At the time, children were not deported with their mothers. Their grandmother, Irma’s mother, was denied entry into the orphanage to claim the children on the grounds that she was Jewish, despite her conversion several years before. Landmesser managed to get Ingrid released into her grandmother’s care because he had publicly acknowledged paternity.27 For whatever reason, he hadn’t been able to acknowledge that his younger daughter Irene was his in the same way. I suspect it’s because he was probably in jail on the day that Irene was born, so he maybe couldn’t, like, sign a birth certificate or something? The book doesn’t address why this difference happened.

16:50 This indicates that between his arrest in July and his conviction, Landmesser was able to get out of jail, at least briefly. I don’t know when or for how long, but what is clear is that after he was convicted in October 1938, Landmesser was sent to Börgermoor Prison Camp in Emsland. Prison camps had conditions similar to concentration camps, with hard labor, terrible food rations, and daily harassment. The Emsland Camps, where Landmesser was sent, had a terrible reputation among prisoners.28

17:17 Penal servitude was considered the hardest form of punishment and could be given for any length of time ranging from one year to life. The Emsland Camps were for the worst criminals, and prisoners with only the, quote, “highest and most severe sentences were sent [there] ... As incorrigible criminals they were subjected to particularly hard, deterrent sentences.”29 These sentences were often outdoors, developing moorlands into arable land or, due to the pressure of wartime preparation, prisoners who were able were sent to fill important jobs in the armament industry. Prisoners from several camps were particularly sent to work at Blohm und Voss as shipbuilders.

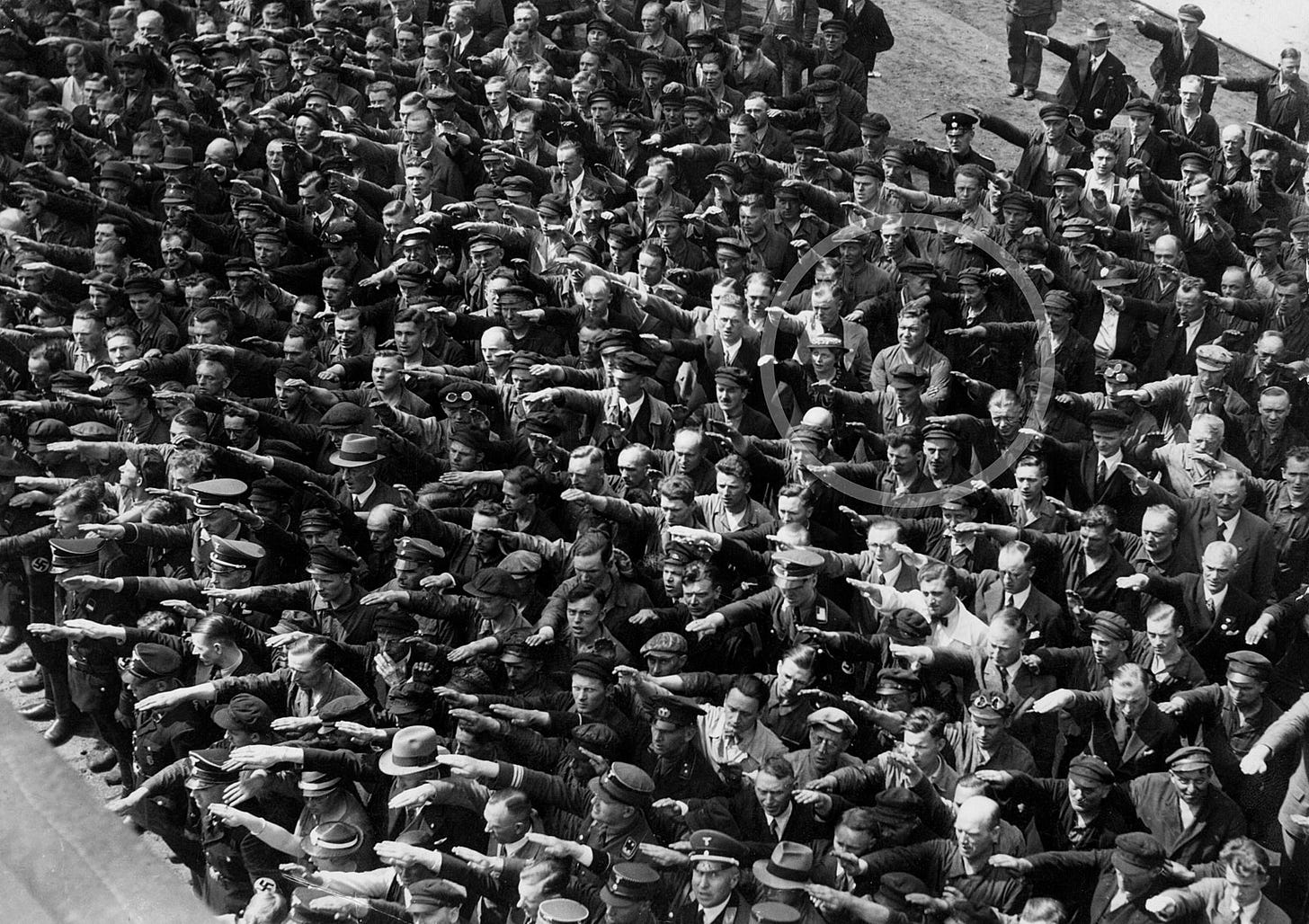

17:53 And this is why history remembers August Landmesser. There’s a photo of workers at Blohm und Voss saluting a ship as it got ready to launch; Hundreds of men doing the Nazi salute to someone speaking out of frame. But someone standing toward the back very clearly is not participating, instead the man has his arms crossed and stands still, squinting at the person speaking ahead of him.

18:14 In 1991, Irene Eckler saw the photo and identified the man as her father, August Landmesser. His identity had been unknown for years, but newspapers were already highlighting the fact that he was refusing to salute. In the 1991 caption for the photo, before he was identified, someone wrote, “Very seldom did anyone dare to publicly refuse to follow the prescribed rituals as did this worker right of centre.”30

18:37 Usually, the man in the photo is credited as August Landmesser, but there is some dispute about it.

18:44 One dispute is about the date. Irene Eckler’s book alternately gives the date of the photo as February 14th 1939 or March 13th, 1939. Either way, it’s mentioned that Hitler had returned to Hamburg for the launching of the warship Bismarck.

18:58 On the other hand, a man named Herbert Diercks doubts the photo could have been taken in 1939 at all. His idea hinges on the fact that August Landmesser would have been a prisoner, in 1939, while he was working at Bluhm und Voss. Diercks believes it was too unlikely that Landmesser, quote, “as a prisoner, would have been allowed to stand in the crowd unguarded.”31 Based on that, he believes that the photo was taken at the launching of the ship Horst Wessel, which was on June 13, 1936, before Landmesser was ever arrested.

19:26 Eckler suggests that this could be possible. According to his family, Landmesser was temporarily employed as a boiler cleaner in 1936. He would have had enough reason not to salute at this point too, having already been denied marriage to his fiancée.

19:39 I have my doubts about this argument, only because there seem to be soldiers in the photo. It seems like Diercks believes that there should have been one guard per prisoner, standing over their shoulder, but that’s not how any prisoner set-up works. It seems very possible, to me at least, that there are several forced prison laborers in this photographed crowd, alongside several soldiers. If Landmesser was there as part of his prison sentence, it makes sense to me that he wouldn’t be photographed in this crowd in chains or something because it was a moment of pomp and circumstance. They would have wanted the appearance of voluntary labor, even if that wasn’t the reality. And he would have known that even without a guard specifically assigned to him, escape would have been difficult if not impossible. I just don’t buy Diercks’ reasoning for a date change, I guess.

20:25 That said, there is a possibility that the photo does not depict Landmesser at all. Another family in Germany claims that the man is Gustav Wegert, a metalworker at Blohm und Voss in the 1930s.32 According to his family, quote, “As a believing Christian he generally refused the Nazi Salute.”33 In a website dedicated to their family history, one of Wegert’s children, Wolfgang, writes,

Both my father himself and my mother as well as many friends and a fellow worker told me again and again, that Gustav never raised his arm for the Nazi salute. From the beginning of the Nazi regime this was his basic principle. If someone greet him with “Heil Hitler” he answered with a simple “Guten Tag” (which means “Have a good day”). [sic] My mother told me often times about her anxiety that her husband could get imprisoned after he received several warnings. It was a miracle in her eyes that this did not happen.34

21:12 End quote.

21:13 According to Wolfgang Wegert ship launches were usually held on Sunday mornings to avoid missing work time, and Wegert refused to attend the Sunday christening ceremonies based on the grounds that he needed to be in church. When asked about this, Wegert was known to reply, “You should obey God more than men.”35

21:28 When I heard the launches were usually on Sundays, I did a quick look at the dates mentioned earlier to see if I could figure anything out. February 14, 1939 was a Tuesday, and March 13th was a Monday, so if the photo was taken on either day it’s possible that it is Wegert and he couldn’t use church to get out of appearing. That said, Hitler’s life is pretty well-documented, so we know that on Monday March 13th he was in Berlin meeting with Jozef Tiso, president of the Slovak Republic, a Nazi client state.36 While it would have been possible to get between Berlin and Hamburg in a day back in 1939, I’m guessing that this known meeting kind of rules out the possibility that the famous photo was taken that day. Especially because just two days later Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia–I have a feeling that with these two events happening the same week, a ceremonial ship launch wouldn’t have been a priority. We do know however that Hitler was in Hamburg for the launch of the Bismarck on Tuesday February 14th, 1939 though.

22:24 June 13, 1936, on the other hand, the date of the launch of the Horst Wessel, was a Saturday. We can assume that Wegert was there because he didn’t have the excuse of church to get him out of it. So if the photo was taken that day, it could be him, especially because the Landmesser family can’t prove definitively that August was working for Bluhm und Voss in 1936.

22:42 The reality is that we may never know who is really in the photograph. Known photos of both Landmesser and Wegert look enough like the man in the famous photo to possibly be him. I’ll include some in the transcript and you can decide for yourself.

22:56 I do want to note an interesting fact I found though. If the photo depicts the launch of Horst Wessel, that ship is still in active service today… in the US Coast Guard. After the end of World War II, the US took the ship, fixed her up, and renamed her Eagle, after the carved eagle on her prow.37 It’s used as a training ship to train sailors to sail the quote-unquote old-fashioned way.

23:28 It’s sad to say, but neither August Landmesser nor Irma Eckler lived for very long after their arrests. About a year after Irma’s arrest in July 1938, she was transferred to a women’s concentration camp called Ravensbrück, near Berlin.38 There, the women were tortured, they froze, they starved, they were beaten and worked relentlessly. The so-called “Final Solution” hadn’t been implemented yet, but would be soon.

23:52 Irma was never released after her arrest, she never saw her children again. In her book, Irene mentions having no memories of her mother. But the women were allowed to send and receive one letter or card per month, provided that the letters were not longer than two pages and only had fifteen lines per page. They couldn’t receive packages or photos from home, though some families found ways around this.39 Unfortunately the Eckler family wasn’t one of them, so Irma never even saw photos of the girls, though in her letters she asked for photos often. Irma did keep legal custody of both her children after her arrest and until her death.

24:29 It is clear from the surviving letters that Irma exchanged with her family that their arrests had soured the relationship between August and Irma. In a letter dated June 1941, she writes, “What’s Ingrid and Irene’s father doing? Does he sometimes see how the children are? He doesn’t have to, as far as I’m concerned.”40 End quote. So she was aware that he had been released by this point. In a letter the next month, she said, “glad that August doesn’t come anymore,” implying that he wasn’t visiting his children much, which I’ll go into why in a little while.41 In November 1941, Irma seems to imply in a letter that August isn’t paying child support, but that they hope to get money from him soon.42

25:08 The last letter the Eckler family received from Irma came in January 1942.43 She doesn’t indicate that anything is amiss, but that same month the so-called Final Solution was decided by the Wannsee Conference.44 In the book, Irene describes what came next using a quote that seems to be from a memoir titled, Milena, by Margarete Buber-Neumann, who was imprisoned in a concentration camp with journalist Milena Jesenska. They both were vocally against the Nazi party and became political prisoners in the late 1930s. The quote Irene seems to have pulled from Milena says–and just a warning, this is kind of tough to hear, so I recommend skipping ahead about a minute if you’re not up for it. Okay, the quote from Milena says:

We still had no idea of what was to happen in the first months of 1942… The order came for lists of names of all who were born cripples, all epileptics, bed-wetters, amputees, asthma sufferers and those with lung diseases, and all the mentally ill. At the time, the SS gave the reassuring explanation that these prisoners would be transferred to a camp with lighter work. A medical commission even appeared and inspected the sick. Then, one day, two lorries stood ready to collect the first load. In the evening, Milena reported, horrified, how the seriously ill were dumped into piles of straw in the lorries; the cruelty with which the suffering were treated. [...] One transport after another left the camp, and with gruesome regularity, the clothes of those killed came back. Once the ‘hereditary ill’ had been exterminated, new lists were made up with the names of all the Jewish prisoners. To Milena and me, this could only mean one thing. But however incredulous it may sound, the Jewish prisoners amongst us [...] tried to persuade us that they were surely only going to be taken to another camp. Why to be killed? That would be madness! They were young, strong persons, fit to work! A young Jewish doctor went with the first transport, and she promised to send a message in the hem of her prison dress telling us of their destination and destiny. We found the note. It read: ‘They have taken us to Dessau. We have to get undressed. Farewell!’45

27:04 End quote.

27:05 This of course is a reference to the gas chambers in some concentration camps. I’m not going to get into it because it’s too horrifying but if you want to know more about this, there’s plenty of information out there. I also really recommend Elie Wiesel’s famous book Night, which is his memoir of his time in Auschwitz. He talks about the whole process of being checked into camps and who was killed and who was put to work.

27:26 There’s some evidence that this mass removal of prisoners from the camps was not simply lamented by their fellow prisoners. A quote in Eckler’s book mentions that it, quote, “caused extreme agitation amongst the Ravensbrück prisoners.”46

27:38 Official documentation from the Third Reich says that Irma Eckler died at Ravensbrück on April 28th, 1942. This is almost certainly not a correct date or location–Irma was murdered by gas at Bernburg sometime in early 1942. The family tried to protest this and find more information, but wasn’t able to.

27:57 August was released on January 19th, 1941, after serving his two and a half years of penal servitude. During this time, he visited his daughters and Irma’s family. The book doesn’t say why, but Landmesser didn’t take his daughters back to his home. This might be because he couldn't afford to care for them–he didn’t have a job immediately upon his release. It might also be because he was classified as a full Aryan German, and since his daughters weren’t fully Aryan Germans he wouldn't have been allowed to care for them. I’ll talk more about that soon.

28:27 By November 1942, we know that August had found work as a lorry driver. The job shows up on a form related to the children’s “assets” which is a wild thing to assume young children might have. It probably has to do with the Third Reich law that Jewish people had to report their wealth.

28:42 His family member, Rudolf Landmesser, wrote to Irene in 1971 that around 1942 August had moved to Rostock, on the north coast of Germany, for a job. The distance from Rostock to Hamburg is a two and a half hour drive today, so I think this probably explains why August wasn’t visiting his children as often, as Irma had talked about in one of her letters. His relationship with Irma’s family had also probably become strained by this point, especially after Irma’s death. It may have also drawn attention to the fact that the girls were Jewish foster kids if a parent was always visiting them. It’s hard to know why he made the choices he did, but I’m choosing to kind of assume the best here.

29:19 August briefly dated a Russian woman, a medical student, living under the false name Sonya Pastschenko. She had been deported to Germany for forced labor, but not much else is known about her. There’s a photo of her with August in Irene’s book though.

29:32 We do know that around Easter 1943, August went to visit Ingrid and Irene with Sonya. It was Irene’s only memory of her father. When Hamburg was bombed in July and August 1943, August “borrowed” the company lorry truck and drove to Hamburg to try to rescue his children. Irene and her foster mother had fled the city, but he managed to find Ingrid, along with her grandparents, and take them back to Rostock.47

29:57 In February 1944, August Landmesser was drafted into the German military and sent to the frontlines with ‘Bewährungsbataillon 999’. (My gosh, I’m sorry for my terrible German pronunciation.) This was a German penal battalion. It’s worth noting that he was embedded with this battalion because it was, quote, “used for very risky operations and was made up of ex-prisoners and ‘undesirables’ who were ostensibly given the chance to prove themselves. It was known that the majority of them would not survive.”48 End quote.

31:01 On November 6, 1944, August Landmesser was reported missing to his family. He had been missing since October 17th, when they were withdrawing from the town of Ston in Croatia. He was later declared dead, and is thought to be buried in a mass grave in Hodilje, near Ston.49

31:16 Irene Eckler’s book documents what happened to the children, especially herself, after they were separate from their parents, a lot of which I won’t bother to get into here. There's a lot of legal documentation about the children and who should take care of them and their pensions, et cetera.

31:30 I will say that the trauma the Third Reich inflicted runs far deeper than most people really talk about. In her book, Eckler gets into how she and her sister were classified differently due to Landmesser not being able to acknowledge Irene early enough. There’s a lot of documentation of the legal back and forth about whether both daughters should be classified as Mischling, and of which degree. Mischling, by the way, is not a word anyone should use lightly, it means ‘half-breed’ in German.50 But it was a legal classification back then, which is why I'm using it now.

31:59 Degrees of this classification were used to clarify how much mixed Jewish and Aryan ancestry a person had. The classification a person received impacted their legal status and what rights they had under Third Reich law. Classifying the two sisters in different ways ensured that they were separated for their childhoods, because children who were wards of the state, which both the daughters became, had to be cared for by people classified similarly to them. Fully “Aryan” adults couldn’t take in half-Jewish children, for instance, even if they were relatives. Furthermore, because August Landmesser and Irma Eckler were both in prison and couldn’t care for the girls or earn money to pay for someone else to care for them, the state had to pay for the upkeep of the children. Because of their different racial classifications, the older daughter Ingrid was given a higher support amount from the state than the younger daughter Irene, meaning that Irene was shuffled around to different families more as people couldn't financially support her. Ingrid was raised by their grandparents, Irma’s family. It’s clear from Irene’s writing in the book that this trauma stayed with her for her whole life. She never fully recovered from this childhood of displacement and feeling unwanted.

33:01 Furthermore, while Ingrid was relatively safe in her grandmother’s care, there’s evidence that Irene was severely injured and even abused while she was still in the orphanage, before being placed with a foster family. She had around 30 documented old scars on her body. An examination by a doctor suggested that they came from falling or being thrown through a glass window.51 I say being thrown because she would have only been around 1, maybe 2, at the time of the injuries–hardly strong enough to break a glass window of her own accord.52 In her book, she says she has no memories of this period of her life.53 However, she suggests that the injuries might have occurred during Reichskristallnacht, which occurred November 9th through 10th, 1938.54 Irene would have been in the orphanage during that time, and only a little over a year old. In a sentence that’s really heartbreaking, she points out that a child of a couple accused of Rassenschande would have been considered, quote, “inferior and unworthy of life,” suggesting that Irene at least believes someone tried to kill her during that November pogrom.55

33:58 Irene survived, however, and was sent out to a foster home soon after. Her grandmother knew nothing of the injuries, the family was barely even alerted that Irene was moved out of the orphanage.

34:08 Dr. Hemann Gerson, who advocated especially for Irene but for both girls with the Third Reich government, should be considered a hero for the work he did for children orphaned by the Third Reich. Gerson wrote directly to Hitler on June 3rd, 1941, appealing for clemency for Irene. He wrote, quote, “In the interest of this child, who, just like [her] elder sister, has ⅝ Aryan blood, may I beg for clemency. What it means to the child to remain Jewish all her life needs no explanation. Everyone in Germany today is well aware of this.”56 End quote. It’s hard to stomach these words today but it’s worth noting how brave Gerson had to be to say that directly to Hitler.

34:47 Irene also remembers that Dr. Gerson would play music with her foster father, Erwin Proskauer. Gerson played the piano, Proskauer the violin, and three other gentlemen joined them on string instruments. Irene was told that they were proper concerts but special just for her, because she was always the only member of the audience.57 This was enormously risky business, as Jewish people were not allowed to be on the street after eight pm.

35:09 Unfortunately, as a Jewish man himself, Gerson was arrested and deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp on July 19th, 1942. He didn’t survive.

35:19 Irene survived the Third Reich only through repeated interventions of good-hearted people throughout her childhood. In early 1942, Irene was kidnapped from her foster home by the Gestapo and taken to a Jewish orphanage. On July 10th of that year, the children of the orphanage were gathered and taken to the train station, supposedly to go to Warsaw, but they were all taken to Auschwitz and killed.58 Irene survived only because as they were being led to the station, she was recognized by a friend of her foster family and sneakily pulled out of the row of children. They hid and managed to escape to Vienna.59 When she returned from Austria, she was hidden inside of a hospital, alongside famous surviving “patients” like Walter Koppel, a film director. Eventually, when her Jewish identification card was, quote, “lost,” it was safe enough for her to emerge from the hospital, but only under the identity Reni Proskauer, the name of her foster family. They treated her as their own and told no one that she was a Jewish child until after the war ended.

36:14 Irene met her sister Ingrid for the first time in 1945, at a meeting of an emergency action group formed to help children who had been impacted by the Nuremberg Laws.60 There’s a photo of them with several other children at this meeting, and their arms are already linked like sisters. It’s a cute photo, though the context is devastating. She also saw a photo of her mother Irma for the first time at this meeting.

36:34 Irene’s foster father, Erwin Proskauer, applied for war orphans’ pensions for both girls, as well as some financial compensation for the wrongful imprisonment of their parents. A belated recognition of their marriage was required for this to work, so he worked hard for that, filing several petitions with the new German government after the fall of the Third Reich. When it was formally recognized in July 1951, the marriage was backdated all the way to March 1st 1935.61 The girls took the last name Landmesser, partially to ensure that they’d receive their pensions.62 It seems at some point that Irene dropped it again, as she published her book as Irene Eckler.

37:10 Irene’s book doesn’t talk much about what happened after the war. Ingrid remained with her grandparents until she was of age to work, it seems. Irene lived in an orphanage after Erwin Proskauer’s wife kicked her out of their house. When she finished school, she worked in publishing then became a teacher. She wrote her book in the 1990s.

37:27 Today, August Landmesser’s name appears on a stumbling stone, or Stolpersteine.63 These brass plates were placed around the streets of Germany in honor of the victims of Nazi persecution.

37:38 Well that’s the story of August Landmesser and his famous refusal to salute to Hitler. I know it’s kind of a sad one, but I hope you enjoyed this episode of Unruly Figures! Come check out photos of the family and so much more on the Unruly Figures Substack. That’s U-N-R-U-L-Y-F-I-G-U-R-E-S dot S-U-B-S-T-A-C-K dot com.

📚Bibliography

Books

Eckler, Irene. A Family Torn Apart by "Rassenschande": Political Persecution in the Third Reich ; Documents and Reports from Hamburg in German and English. Translated by Jean Macfarlane, Horneburg Verlag, 1998.

Websites

“August Landmesser.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Nov. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/August_Landmesser.

Blakemore, Erin. “Germany's World War I Debt Was so Crushing It Took 92 Years to Pay Off.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 27 June 2019, https://www.history.com/news/germany-world-war-i-debt-treaty-versailles.

“Definitions for Rassenschanderassen·Schande.” What Does Rassenschande Mean?, https://www.definitions.net/definition/rassenschande.

“March 1939.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 2 Jan. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/March_1939#March_13,_1939_(Monday).

“Mischling.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 13 Dec. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mischling.

Ruddy, John. “Birth of the Eagle: How a Nazi Training Ship Found Its Way to the Coast Guard Academy.” The Day, The Day, 10 July 2021, https://www.theday.com/article/20210710/NWS01/210719936.

Wegert, Wolfgang. 1936 - Just One Refused the Nazi Salute, http://wegert-familie.de/home/English.html.

Unruly Figures is an affiliate with Bookshop.org. That just means that if you click one of the links above to buy something, I’ll receive a few cents from your purchase, but it won’t cost anything extra for you!

“August Landmesser.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Nov. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/August_Landmesser.

Wikipedia

Eckler, Irene. A Family Torn Apart by "Rassenschande": Political Persecution in the Third Reich; Documents and Reports from Hamburg in German and English. Translated by Jean Macfarlane, Horneburg Verlag, 1998.

Eckler, 14

Ibid.

Blakemore, Erin. “Germany's World War I Debt Was so Crushing It Took 92 Years to Pay Off.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 27 June 2019, https://www.history.com/news/germany-world-war-i-debt-treaty-versailles.

Blakemore

Eckler, 12

Ibid.

Eckler, 17

Ibid.

Eckler, 25

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Eckler, 27

Ibid.

Eckler, 31

Eckler, 33

Ibid.

“Definitions for Rassenschanderassen·Schande.” What Does Rassenschande Mean?, https://www.definitions.net/definition/rassenschande.

Eckler, 14

Eckler, 39

Ibid.

Ibid.

Eckler, 39

Eckler, 44

Eckler, 45

Eckler, 47

Eckler, 49

Eckler, 51

Wikipedia, “August Landmesser”

Wegert, Wolfgang. 1936 - Just One Refused the Nazi Salute, http://wegert-familie.de/home/English.html.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“March 1939.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 2 Jan. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/March_1939#March_13,_1939_(Monday).

Ruddy, John. “Birth of the Eagle: How a Nazi Training Ship Found Its Way to the Coast Guard Academy.” The Day, The Day, 10 July 2021, https://www.theday.com/article/20210710/NWS01/210719936.

Eckler, 55

Eckler, 126

Eckler, 129

Eckler, 131

Eckler, 140

Eckler, 143

Eckler, 145

Ibid.

Eckler, 147

Eckler, 209

Eckler, 210

Wikipedia, “August Landmesser”

“Mischling.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 13 Dec. 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mischling.

Eckler, 59

Eckler, 180

Eckler, 58

Eckler, 61

Ibid.

Eckler, 99

Eckler, 157

Eckler, 195

Ibid.

Eckler, 223

Eckler, 235

Ibid.

Wikipedia, “August Landmesser.”