Thanks for checking out Unruly Figures! I’m able to keep these transcripts, bibliographies, and more free because of the amazing people who help support this work. Want to support independent and in-depth research? Subscribe now!

Today I’ve (finally!) got the transcript and bibliography for Unruly Figures episode 7, Manuela Sáenz. At the beginning of each paragraph is a time code for where you can find that in the episode. I also do endnotes throughout, in case you want to follow up with a resource for more reading!

🎙️ Transcript

Here’s the episode:

0:05 Hey everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s greatest rule-breakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today I’m going to be covering a woman who is often left out of our histories of Latin America: Manuela Sáenz.

0:19 Sáenz was a friend and lover of Simón Bolívar, and was often referred to as the “Libertadora” to Bolívar’s “Libertador.” She’s widely remembered by people in South America today, but a lot of historical accounts, when they include her at all, either romanticize Sáenz as a beautiful woman passionate for both freedom and Bolívar, or they downplay her role to one pivotal moment when she saved Bolívar’s life. For a lot of my coverage, I’m going to rely on For Glory and Bolívar by Professor Pamela S. Murray, which is one of the only books about Sáenz in English. Fortunately for us, it’s also one of the most in-depth books about her.

0:53 Real quick, before we get into her story: For a full transcript of today’s episode, head over to Unruly Figures dot Substack dot com. That’s U-N-R-U-L-Y-F-I-G-U-R-E-S dot S-U-B-S-T-A-C-K dot com. In addition to the full transcript, you can also get ad-free episodes, a bibliography of my research, photos of everyone I’m covering, discussion threads, and so much more. So check it out!

1:20 All right, let’s hop back in time.

1:21 We’re going to Latin America’s “Age of Revolution,” a time that saw the European Enlightenment come to bear fruit in the revolutions of Central and South America against colonial powers. Manuela Sáenz was born at the perfect time to bear witness and participate in this. Born in December of 1797, she was the perfect age to grow up in the new liberal-republican order of South America.

1:43 But let’s back up. Manuela’s birth, like our previous subject Anne Bonny’s, was considered illegitimate but in an interesting legal way. In Quito, Ecuador, where she was born, her parents had the unique option of marking her down as a foundling child, or hija exposita. It means, literally, “child of unknown parents,” though her parents were both very much known, but it was a designation specially designed to protect the reputations of both of her upper-class parents. That both her parents were considered social elites really helped to mitigate the stigma that would have come with being an illegitimate child.

2:17 We don’t know much about her childhood though. We know she probably never had much of a relationship with her mother, Joaquina Aizpuru. The Aizpuru family was a wealthy creole family living in the most prestigious part of Quito. That Joaquina got pregnant through an affair with a married man who was a friend of the family would have been very embarrassing for them; codes of honor and decency were very strictly enforced. The thirty-year-old unwed Joaquina did what social norms dictated she had to do: Gave birth in secret and gave the baby up to the local La Concepción Convent, an organization known for taking in this kind of quote-unquote “orphan.” The sad truth is that Manuela may have never seen Joaquina again, though she would know who gave birth to her and would clash with the Aizpuru family later in her life.

3:00 Manuela’s father, Simón Sáenz de Vergara y Yedra, was a completely different story. Like we talked about in Anne Bonny’s episode, it wasn’t totally unexpected that a man would have an affair, and the stigma that would have haunted Joaquina never would have impacted Simón the same way, despite the fact that he was the married one. The patriarchy! It’s unfair! Fortunately for the baby, Simón Sáenz was willing to provide for her and even formally acknowledge her, which is how she gained her last name. Though raised by the nuns at La Concepción, she was integrated into the family, which, among other things, gave her the right to be treated as a respectable woman who was to be addressed with the honorific Doña, meaning “madam” or “lady.”

3:39 The convent they chose was a reflection of the affluence both her parents’ families enjoyed: There was a one thousand-peso minimum dowry required to ensure her acceptance at the convent, which was a lot of money then and now.

3:52 Side note: I know that normally in episodes I do an inflation calculator to help illustrate how much something really cost, but in trying to convert 18th century Ecuadorian pesos into US dollars today, I just found that to be impossible, in part because Ecuador has changed their currency a few times since Manuela’s birth. Today Ecuador actually uses the US dollar and has since 2000. Suffice to say that 1000 pesos would have been an unthinkable amount of money for an average or impoverished family in Quito in 1797.

4:21 La Concepción would have been a beautiful place to grow up, however. Most of Quito’s inhabitants lived in cramped adobe houses, whereas the Concepcionista nuns lived in a spacious and elegant campus that rambled for more than a block. It contained beautiful covered passages with a garden in the center—the convent is actually still in operation, and on the Substack I’ll post some more current photos of it. Each nun had her own ‘house’ or cell with a patio and a slave or servant who prepared all her meals, and the convent itself had its own bakery, kitchen, workshops, and more—a universe unto itself. It remains the oldest convent in Quito, and for a long time was aligned with the region’s elites. They had a tradition of admitting daughters from only the most noble of families to become nuns. The hundred nuns were of mostly white or creole origin. Of course, the monastery reflected Quito’s socioeconomic realities as well: Those 100 nuns presided over a veritable army of thirteen hundred maids or servants who were mostly Indigenous or mestiza, a person of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry. Creole, for those unfamiliar with the term, is a racial category of persons of mixed European and Black or African ancestry.

5:20 The cloister was also a hub of activity. If you hear ‘nun’ and ‘cloister’ and think of a remote place for silent contemplation and prayer, think again. The Concepcionistas were known for their pragmatic dedication to industry. They manufactured lace and fine embroidery, enameled wood and handicrafts, and they also taught the local privileged young girls how to read and write, how to sew and embroider, and how to cook fine delicacies that one might make for a special occasion (but not everyday cooking for meals). Candymaking, to my surprise, was actually heavily associated with female gentility at this time.

5:51 In his book Lima: A Cultural History, James Higgins notes that in certain larger convents, like La Concepción, the rules for nuns were generally more relaxed across Spanish America. Nuns could receive guests, and quote, “having a nun in the family was seen as conferring social prestige.” One European visitor to a convent in the 1830s, a little after Sáenz’s time there, noted (and this is a long quote):

Convent rule is nowhere to be seen. It is a house where everything goes on that goes on in any other house. There are twenty-nine nuns; each of them has her own lodging, in which she is cooked for, works, teaches children, chats, sings, in short, does as she fancies. We even saw some who were not wearing their order’s habit. [...] It is a way of life that is beyond comprehension; one would be tempted to believe that these women have taken refuge in this cloister to be more independent than they would have been in the outside world.

6:52 End quote.

6:53 Which, I mean… Yeah. Can you blame them? I mean, this is like Anne Bonny and piracy all over again. When you don’t want to submit to being ruled by someone else, you find a way out. Sometimes that’s through legal means and sometimes it’s not.

7:05 All that to say that even in her so-called orphanhood, Manuela Sáenz grew up relatively privileged.

7:12 Now, as I mentioned, Manuela was fairly well integrated into the larger Sáenz family. She knew and loved her seven half-siblings, and while circumstances would separate her from many of them throughout her life, she would remain in touch with at least a few. Her father, Simón Sáenz, had plans to arrange a marriage for her. As you’ve probably heard before, marriage at this time wasn’t really thought of as a source of, like, emotional well being so much as an expedient way to ensure the family’s interests; in fact it was so important in the Spain and the Spanish Americas that the year 1778 had actually seen the law Real Pragmatica passed, which was designed to increase a parent’s control over a child’s marriage by giving them the right to legally challenge it.

7:52 (This law has actually never been repealed and had potential ramifications for the current royal family of Spain back in 2014 when King Juan Carlos I wanted to abdicate. Obviously I won’t get too much into this, but basically because Real Pragmatica was never formally rescinded, some people believed that Juan Carlos’s children and grandchildren weren’t eligible to ascend to the Spanish throne because they weren’t of 100% royal blood. Nevertheless, Juan Carlos’s son, Felipe, peacefully ascended to the throne in 2014, with his very beautiful but non-royal wife by his side.)

8:25 In a similar vein of unapproved marriages, there’s a legend that Manuela Sáenz tried to run away from the convent to elope with a young Spanish officer. We don’t have proof that this ever happened, but certainly if it did her father would have challenged the marriage. What we know for sure is that Simon Sáenz married Manuela to his wealthy business associate James Thorne, who was, quote, “one of a small number of British entrepreneurs and fortune seekers who had begun trickling into the Spanish colonies at the end of the Napoleonic Wars.” End quote.

8:54 When she was nineteen years old, Sáenz traveled to Lima, where Thorne lived, and the two were married on July 27, 1817. At this point, Sáenz’s last name would have changed to reflect her marriage, but I'm going to keep calling her Sáenz for reasons that will soon become clear.

9:08 With this marriage, Sáenz became the mistress of Thorne’s household, which included command over an unknown number of slaves and servants, as well as access to fine luxuries. She also became the object of his affection. Though the marriage was arranged, Thorne came to love her, and we see some of that in their surviving correspondence. In letters he sent her while he was away on a business trip, he called her the, quote, “most beloved wife of my heart,” and “my precious chinchita.”

9:34 Sáenz also became his confidante and business collaborator, helping him by conducting various transactions on his behalf. She possessed his general power of attorney and was able to supervise his affairs in Lima, as well as act on her own behalf. Certain legal and financial transactions–the buying, selling, and freeing of slaves, for example–usually could only be performed by men, but we know that while Thorne was away on one trip Sáenz emancipated the young daughter of one their slaves (but not the mother).

10:02 In addition to Thorne’s affairs, she used this legal power she had to claim her maternal inheritance. She hired a lawyer in Quito to essentially subpoena people to confirm the identity of Sáenz’s parents and the circumstances of her separation from them. When Mariano Ontañeda, a Mercedarian friar, confirmed Joaquina Aizpuru as Sáenz’s mother, that immediately gave her the right to a portion of the estate of Joaquina’s father, Don Mateo Aizpuru. Of course, nothing was so easy and it would take a very long time and a trip to Quito for Sáenz to get the money she was legally entitled to under Spanish law.

10:34 Now, even when she wasn’t acting on Thorne’s behalf, Sáenz’s life in Lima was surprisingly free. Women had an unusual degree of freedom there, especially considering the time–they were allowed to move around the city unchaperoned and could mingle freely with anyone of any class. It often shocked European visitors in fact, and a man named Robert Proctor noted that, quote, “it is not thought at all inconsistent with propriety for respectable females to sit [on benches in the plaza and public walkways] laughing and talking for an hour after dark… in fact, the ladies here regulate their own conduct.” End quote. Obviously, Proctor thought this was terrible, but I think it’s awesome and I bet Sáenz loved it too.

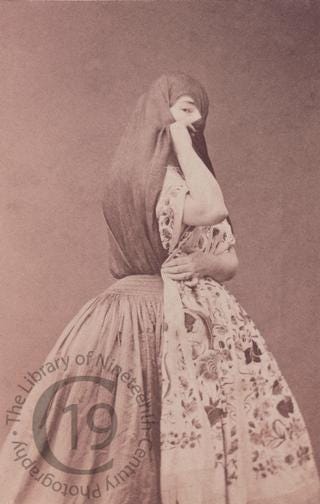

11:15 Women in Lima wore a traditional yet unique outfit that actually enabled this freedom and mobility: the saya y manto. The saya was a long, snug skirt, usually pleated and with a decorative fringe at the hem and raised to show off the feet and ankles. In paintings it looks pretty but I think it probably would have been difficult to walk in. The manto was, quote, “a thick veil fastened to the back of the waist; from there it was brought over the shoulders and head and drawn over the face so closely that all that was left uncovered was a small triangular space sufficient for one eye to peep through.” End quote. I said it was traditional yet unique because it had Moorish origins and so came over to South America with the Spaniards, but the outfit was not popular outside of Lima.

11:58 It’s interesting because the saya y manto was originally designed to serve men’s interests: hiding their wives from other eyes and trying to ensure a woman’s chastity by keeping her body hidden. But women quickly claimed it for themselves and began using it to get around the city in disguise. As Murray notes, in this outfit a woman’s husband might not recognize her if he passed her on the street. All that was visible was one eye! That anonymity facilitated transgression against limits imposed on women by the Catholic Church and the government. Both tried to ban the saya y manto for precisely this reason, but it’s disguising effect was its own safeguard–it was difficult to ticket a woman they couldn’t identify. Women in Lima went on wearing it regardless of what the powers that be said. Even though Sáenz would probably have never seen this fashion before coming to Lima, she probably quickly adapted to it, exploiting its obvious advantages.

12:50 As an adult, Sáenz was reputedly beautiful, but stood out more for her sense of humor as well as her free-spiritedness, generosity, and compassion. She was lighthearted, generally, and once confessed to her husband, quote, “I [tend to] laugh at myself,” revealing a level of confidence that’s not easily achieved. She was occasionally impulsive and really loved a joke or a prank, anything that pushed the boundaries. There’s a story from a friend of hers that once, when they were going horseback riding, Sáenz appeared disguised as a man, in an officer’s uniform and with a fake mustache. Before anyone could be sure of her identity, she took off, quote, “forcing her companions to chase after her and thus confirm her identity.” End quote.

13:31 If you know anything about South American history, you know that by this point in history Spain was starting to lose their grip on their colonies in South America. Between Napoleon’s invasion of Spain, their own crises of rulership, and the rebellions by slaves in various colonies, anti-Spanish sentiment in South America was growing steadily. By 1810, “increasingly bitter wars” were erupting between patriots and loyalists. And women played key roles in these battles.

13:58 Urban upper-class women, like Sáenz, nurtured the patriot cause by, quote,

“hosting informal gatherings (or, tertulias) that had served as forums for anti-Spanish criticism [...] they also gave much-needed financial, material, and logistical support to the leaders of the first insurgent armies. [...] Women of all classes were integral to the patriot struggle and involved in virtually all aspects of it. They routinely served as spies and couriers as well as nurses, arms smugglers, and provisioners of food and clothing. Although usually in disguise, they served occasionally as combatants as well. They also stood out for their role as patriot army recruiters. Indeed, the efficacy of their recruitment method–which involved bribing or otherwise persuading the loyalist troops to defect to the patriot side (a process generally known as ‘seduction’)--had become a source of worry for Spanish officials.”

14:48 End quote.

14:49 Sáenz became involved in the conflict on behalf of the patriots, and supported Jose de San Martín, who had already successfully won freedom for Argentina and had crossed the Andes mountains to work against the Spanish in Peru. She recruited men for San Martín, especially in the Numancia regiment of the Spanish military, which her half-brother Lieutenant José María del Campo was a member of. By July 1821, she was an open supporter of the new patriot government established by San Martín, answering the call for donations of fabric and clothing to resupply the patriot army.

15:21 Her support for independence won her recognition and public honor. She was among the first people inducted into San Martín’s Order of the Sun of Peru, the highest award still bestowed by Peru today. Female members were not eligible for the same benefits as their male counterparts, i.e. government office and a pension, but their male relatives were granted preference in applying for public office afterward. The public recognition from this and other awards gave her some of the public honor and prestige that had been denied to her as a child due to her birth status.

15:50 In April 1822, Sáenz returned north to Quito. Her way was cleared by patriot forces who had driven the Spanish out of this part of Peru. The reasons for her first trip home in five years were two-fold: One was to visit her father, whose loyalist beliefs made him unwelcome in his longtime home; he was already planning to move back to Spain that year. The second was to try to settle her pending claim to an inheritance from her mother. The only surviving relative on that side, Ignacia Aizpuru, refused to acknowledge Sáenz’s claim at first, but eventually acquiesced and offered her a flat sum of ten thousand pesos to be paid within two years. It wasn’t the full amount that Sáenz was entitled to, but she decided to drop her original demand theoretically to keep the peace, though I don’t see what peace there was to keep at this point, honestly.

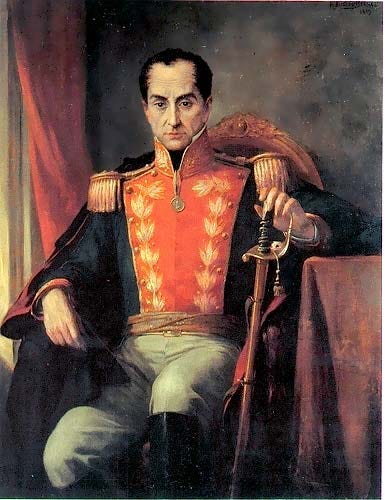

16:36 But her visit to Quito would be life-changing for other reasons: the famous Simon Bolívar was due to arrive there around the same time. Bolívar had earned the title The Liberator in 1813 for his role in Venezuela’s revolution against Spain and was, at that point, the supreme commander of Spanish America’s most successful army–together, they had broken Spain’s hold over northern South America.

16:59 Bolívar was also a conqueror, not just a revolutionary. In the power vacuum that came the fall of Spanish power, known as the Viceroyalty of New Granada, Bolívar created a Colombian republic that would come to control the combined territories of modern-day Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama. In fact, in the same breath that he’d helped drive the Spanish from Quito he had also annexed Quito into Gran Colombia. It was his dream to create a South American unity under one strong government–just not the Spanish one. He was kind of similar to Napoleon in this way, and in fact strongly admired Napoleon.

17:34 Bolívar arrived in Quito on June 16th, 1822. Residents of Quito turned out in droves to welcome the Liberator to their city. They decorated their homes in red, blue, and gold to symbolize their annexation into Gran Colombia and their new identity as Colombians. He entered the city in a parade with seven hundred horsemen then ascended to a decorated platform where he received a welcome from the men of the city as well as young women dressed in classical nymph costumes. This really surprised me at first, but apparently he was seen as a quote, “New World Caesar Augustus” so perhaps it’s not that surprising? That night, the prominent Larrea family threw a private ball in his honor at their home. According to legend, it was there that Sáenz and Bolívar met and began their romantic relationship. She was twenty-four and he was thirty-nine.

18:24 I want to throw out that society had changed enough in the twenty-five years since her parents’ affair that an extramarital affair was slightly less frowned upon than before. Illegitimacy rates were as high as thirty-five percent through the eighteenth century, which signals that these affairs were, quote, “fairly common among elites in late-colonial Spanish America. They were encouraged both by the widespread practice of arranged marriages and the gap between eliters’ public and private worlds. [...] As long as a person (either a man or a woman) remained discreet about it, he or she could carry on an affair without fear of damage to honor and reputation.” Of course, there remained some double standard and so women had to be a bit more discreet, but I say this because Sáenz’s status as Bolívar’s mistress became quickly pretty well-known and did not result in her facing recriminations as we might have thought.

19:15 This happened in part because of the feeling of relief that spread throughout major cities like Quito following their freedom from Spain. After years of conflict, there was a rise of a, quote, “new, more easygoing, democratic culture and sociability,” which included a, quote, “unprecedented mingling of the sexes and classes” through dances, gambling, cockfights, and more. We can understand this affair, and others like it, through this cultural shift.

19:41 Bolívar and Sáenz fell deeply in love. He had had many fleeting romantic relationships in his life, but had always prioritized his larger political goals. According to many biographers, quote, “He rarely lingered in cities and, when not absorbed in a military operation, was almost always in a hurry to get back to his troops,” which of course would make it difficult for a real relationship to take root. With Sáenz however, things shifted–instead of leaving her behind, in 1823 she began to accompany him while he travelled as a member of his staff. He once admitted to her that he loved her for her, quote, “delightful temperament” more than anything else–apparently, as the years of battle weighed on him, she became one of the few people who could lift him out of his darker moods. Years into their affair, in response to someone’s criticism of [her] impulsivity, Bolívar called her, quote, “[our] dear madwoman.”

20:33 Now, Sáenz’s husband, Thorne, doesn’t play into the picture much from here on out, so I’m just going to tell you the rest of their story quickly: He learned about the affair and begged her to end it for years, first out of heartbreak and then later probably more out of concern for both of their reputations. She was pretty frank with him, saying that she loved Bolívar and not Thorne and could not be convinced to abandon him; concerns about honor no longer mattered to her. There is some evidence that Thorne may have at some point actually contacted Bolívar, asking him for the, quote, “return of his wife.” He may have even threatened to force Sáenz into a divorcio, a women’s prison where husbands could send their wives for perceived bad behavior. Which, you know, just kind of makes me shake with rage. However, there’s no evidence that he actually did do this to Sáenz and she never returned to him. The two remained legally married until Thorne died in 1847, maybe due to the difficulty of divorce. He eventually began seeing another woman as well and gave up on begging Sáenz to return to him.

21:42 So, as I mentioned before, Sáenz managed to become a member of Bolívar’s staff. By December of 1823, she had become his personal archivist, a very unusual role for a woman to hold at this time. It allowed her to follow him wherever he traveled, as well as receive a paycheck, ensuring that she could be independent from her husband. Without this paycheck, she would have been dependent on either her husband or Bolívar for everything, which can feel like a dangerous position for a woman to occupy, no matter the time period.

22:11 For several months, she followed Bolívar by about a day’s ride and along a separate route that remained secret, especially as they passed through royalist-dominant regions. She kept the archive of his documents and records of his work with her, and was accompanied by guards. The only people who knew where Sáenz was were her guards, Bolívar, and a few trusted couriers who carried letters and documents between them.

22:34 This set up lasted for about a year, but in 1825, Bolívar was having doubts about their relationship. In the spring, there’s evidence he had an affair with someone else. He also wrote to her, saying, quote, “I see that nothing in the world can unite us under the auspices of innocence and honor.” End quote. His concern was basically that this affair could be very damaging to their reputations, and in fact some of his close allies and advisors had been trying to tell him that his ongoing affair with a married woman was too public and too scandalous. He wrote, quote, “I wish to see you free [of your husband] but, at the same time, innocent… I cannot stand the idea of being the robber of a heart that was once virtuous and that, because of me, no longer is.” End quote.

23:19 However, [laughs] however, early in 1826 when Sáenz hinted that she really might reconcile and go to London with Thorne, perhaps to rekindle their relationship and even meet his family there, Bolívar couldn’t take it. “Do not go anywhere… not even with God Himself,” he commanded her, going on to say, quote, “I, too, want to see you and see you again; and touch you and smell you and taste you and unite you to me through all the senses… You are the only woman for me.” End quote.

23:50 So, you know, whatever his initial ethical misgivings about their relationship, ultimately his, quote, “pure and guilty love” for Sáenz won out. Those are his words, by the way: Pure and guilty. I can’t find any proof that Bolívar was a poet, but something about the phrase strikes me as poetic. Maybe he wrote some and just none of it survives.

24:09 During this period of reckoning, Sáenz was heartbroken and potentially suicidal. She wrote to a mutual friend of theirs, quote, “misfortune has befallen me, all things [must] come to an end, [Bolívar] no longer thinks of me.” She added that she was, quote, “miserable… ready to do something crazy” and quote, “might even die” because Bolívar had moved on.

24:29 A lot of historians call this melodrama, which makes me really uncomfortable–I have a personal policy of never assuming someone talking about suicide is joking. I’m not sure what might have been considered quote-unquote normal behavior for a woman in South America in the 1820s facing heartbreak. This particular part of cultural history is not my expertise and I couldn’t easily find more information, so I can’t say whether Sáenz is operating within a defined gender role by saying that she might die if Bolívar abandoned her. But, I don’t know, maybe this whole “might even die” statement is an 1820 equivalent of “I can’t even” or “I’m dead,” which on their faces are dramatic statements but we all know it’s just Millennial meme culture. My point is that I don’t know. Was Sáenz really feeling suicidal over Bolívar’s potential abandonment? I mean, maybe. She had blown up her hard-won reputation and respectable life for this man. I wouldn’t be surprised if a woman living in her economic and social reality felt trapped by this and decided that the only way out was suicide. I think today it would be believable if someone died by suicide because of this very situation, I can’t imagine the potential terror she might have felt going through this situation in a world where the men around her dictated the terms of her survival in a much more stark way than women in the US face today. All that to say that this was a dark period for our hero.

25:53 When Bolívar realized the folly of trying to end the relationship with the woman he idolized, his words, she moved to his headquarters at La Magdalena to be closer to him. This move very clearly signaled her growing importance as his mistress, friend, and ally; having her own residence near his was a clear signal that she was, at the very least, a semi-official mistress that he was willing to acknowledge in public.

26:16 Soon, Sáenz wasn’t only a member of his staff and his mistress; she became a trusted member of his inner circle, which Pamela Murray described as, quote, an “itinerant family.” She was known for her personal and political loyalty to Bolívar, standing out even among his inner circle. One of the rules he’d put in place for his archivist was that she wasn’t to release anything with Bolívar’s express permission, which was occasionally frustrating his generals. She also began receiving petitioners on his behalf, as well as visitors seeking any sort of special favor from him. She began to act as an intercessor on behalf of refugees, taking cases to him that she thought he might care about.

26:55 Like other members of the inner circle, Sáenz supported Bolívar’s political goals unquestioningly, even his plan to unite all of South America under Gran Colombia. Not to get too ‘dun dun duuuun’ about it, but certainly his replacing of Spanish colonial power with his own power didn’t make a lot of the patriots from the revolutionary wars happy. I’m making a very complicated story very short when I say that people began to revolt. Conspiracies to overthrow Bolívar developed, including one that came from within the military on January 25, 1827. Many rank and file soldiers were frustrated not just with the power grab but also with missing wages and a shortage of food for the military. They mutineed and seized control of the Palace and Plaza de Armas in Lima, sending officers who were loyal to Bolívar out of the city.

27:42 Sáenz went to Lima personally to try to mitigate the impact of this uprising. She dressed in a colonel-style uniform and gave inspiring speeches (plus wads of money) to sergeants and corporals, trying to get them to stay on Bolívar’s side. She had some success, and was also able to use her time there to smuggle out several various documents to preserve in the archive.

28:02 On February 7th, in retaliation, several troops barged into Sáenz’s house at Bolívar’s headquarters and tried to force her to go back to Lima. She managed to hold them off for a night by feigning an illness, which amazes me that that worked, but the next day they took her to Lima and confined her at the women’s prison at the convent of Las Nazarenas. She became a government prisoner and wasn’t ever tried for her supposed crimes. Finally, after a lot of letter writing and insisting on her rights under the newly restored Peruvian Constitution, it seems like the people holding her kind of… got sick of her? And released her on March 23rd. She actually stayed in Lima, trying to get justice for her unlawful imprisonment–and also, probably stoke public opinion against the new Peruvian government–but was eventually kicked out of the city that she’d been forcibly brought to! The new Peruvian Minister of Foreign Relations, Manuel Lorenzo Vidaurre (which, I’m sorry if I’m not pronouncing that perfectly) characterized her as “scandalous” and, quote, an “insult” to “the public’s honor,” before giving her until April 10th to leave Lima.

29:05 She waited until April 11th to board a ship bound for Guayaquil, which was the first major port in Gran Colombia on the way out of the Republic of Peru. By this point, all of her politicking on behalf of Bolívar had officially earned her the nickname “La Libertadora,” which is the feminine form of Bolívar’s nickname, The Liberator.

29:22 Soon after landing in Guayaquil, Sáenz went onward to Quito and then Bogotá, where Bolívar was at his personal family residence. There, Bolívar was facing internal issues with the people he’d long considered allies. His Vice President of Gran Colombia, Francisco de Paula Santander, had begun openly criticizing Bolívar, especially his pro-dictatorship ideas and his plans for South American domination. Factions were splitting and developing, and began manifesting in street violence by early 1828.

29:50 Sáenz was brutally antagonistic toward Bolívar’s opponents, calling them “wicked men” and praying, quote, “God grant that [they]...die.” As some of his allies fell away, he came to rely more on her advice. She began collaborating with his main followers, known as the Bolivarians. The loose group was made up of the country’s oldest and wealthiest families, members of the clergy, members of the Colombian army, and a few British or Irish officers that had stuck around after helping in the revolution against Spain.

30:19 Using a political stalemate that they had themselves largely manufactured, in June 1828 the Bolivarians declared that the country was, quote, “in crisis” and used it as an excuse to call on Bolívar to assume emergency dictatorial powers. A lot of moderates actually agreed with this proposal, seeing dictatorship as a short-term, practical measure; a “necessary evil.” He accepted the call and promised to only retain the powers until the liberals in the nation had calmed down.

30:52 To celebrate and gain support, Sáenz threw a huge party for Bolívar’s birthday on July 28th at his private residence. The party was, smartly, open to the general public and included free food and drink, as well as entertainment provided by a military band. Of course, this party got a little out of control and spawned a scandal: Someone made a dummy of Vice President Santander and gave it a mock trial before executing him in effigy. Some people blamed this on Sáenz, saying that she had either had the idea or encouraged the celebrants to keep going. She denied it, but it did alienate a few of Bolívar’s supporters further because it associated her with the most extreme Bolivarians and confirmed the public’s perception of her as someone with too much influence behind the scenes. Some people began referring to her as “la presidenta,” which some of Bolívar’s government allies were worried would undermine both Bolívar and the very government they were trying to save.

31:45 But if Sáenz was starting to be associated with the extreme Bolivarians, the extremist end of the Santanderista opposition was becoming a dangerous force. This group had its roots in political clubs, called círculos, attended primarily by university students and idealistic young lawyers. On August 10th, they tried to assassinate Bolívar in a plan that sounds oddly like a combination of Caesar’s assassination and Lincoln’s assassination, which happened thirty years after this attempt. They planned to seize him while at the city’s theatre and stab him to death, but they were thwarted by Sáenz, who had apparently learned of the plot and showed up at the theatre to warn him.

32:21 Since that didn’t work, on September 25th more conspirators sprung into action. Sixteen artillery soldiers and ten civilians, led by Venezuelan officer Pedro Carujo broke into the presidential palace and made their way to Bolívar’s bedroom. Astonishingly, Bolívar had been warned of this attack by an informant but had, quote, “scoffed at the news,” sure that it was just a rumor! He didn’t make any special arrangements for security. Instead, he asked Sáenz to stay the night, though she normally slept at a separate residence, just to read to him.

32:54 The two had fallen asleep by the time the conspirators broke in. She woke first, startled by his dogs barking in the night. When she woke Bolívar, he apparently tried to run to the door, and she had to redirect him to the window, persuading him to escape through it into the street below. It was a narrow escape: He waited to jump until the attackers were trying to force their way through the locked door.

33:15 Sáenz opened the door for them, and they grabbed her, demanding to know where Bolívar was. Thinking quickly, she told them that he was in the Council Room, which they demanded that she lead them to. She began to, but suddenly decided to claim that she didn’t know where the Council Room was. When they eventually forced her to continue, she stopped to take care of a wounded man loyal to Bolívar, which again infuriated them. They began beating her with the sides of their swords; Sáenz, who was actually already sick that night, was severely injured and would feel the effects of their attack for weeks. Nevertheless, she still tried to help people as they forced her forward, effectively slowing them down and giving Bolívar time to get far away.

33:55 Finally, the attackers realized they’d failed and they fled. Sáenz found a doctor to take care of the people wounded inside the presidential palace, then went in search of the Liberator. She found him in the plaza, safe but shaken. Supposedly for the first time ever, he acknowledged that Sáenz was, quote, “the Libertadora del Libertador.”

34:14 This has all sorts of political consequences for Colombia, but this podcast isn’t about that so I’m going to mosey right along.But just know, there is a ton that I’m skipping here that if you’re into that type of military and political history, I really recommend you go check it out. Cool. So, while Sáenz collaborated with the regime to suppress further uprisings against Bolívar, the Liberator himself left Bogotá in February 1829 to go to Guayaquil to oversee battles against an encroaching Peruvian army. The two wouldn’t see each other for eleven months.

34:50 In April 1829, Sáenz became embroiled in a controversial project: Converting Gran Colombia into a monarchy, which would have included support from one of the major European powers. Many members of Bolívar’s government blamed republicanism and the whole government structure for all of the political turmoil that Central and South America had been facing since the withdrawal of Spanish power, and they believed the only way to regain stability was to return to monarchical rule.

35:18 The plan was that an heir from one of the royal houses of Europe, preferably the French Orleans dynasty, would move to Colombia to take over once Bolívar stepped down. His health was declining rapidly and they really needed to do something. If it seems weird that they wanted to go all in with France so soon after having overthrown the Spanish, it has to do with the popular culture of the elites in South America at this time; many creole elites, especially of Sáenz’s generation, were a fan of French language and culture. In May 1929, Sáenz hosted a special reception for the French delegation to Gran Colombia, including King Charles X’s personal envoy, Monsieur Charles de Bresson. Bolívar, however, decided against pursuing this avenue.

36:02 Through the rest of 1829 and 1830, Bolívar’s regime grew more unstable and his health declined rapidly. He was suffering from tuberculosis. He resigned the presidency on March 1, 1830 amid political tension, and then left the country in May because political tension was still rising. Sáenz struggled with his decision and ultimately stayed behind, convinced that his exile was temporary. In July, she began working toward his comeback by rallying local Bolivarian sentiment and cultivating sympathy within (i.e. giving gifts to) certain battalions who guarded the presidential palace. By August, a budding rebellion could be seen especially among conservative-minded wealthy elites who regretted Bolívar’s departure.

36:45 Of course, the Santanderista government wasn’t loving this behavior from Sáenz, especially because she was not being very secretive. I mean, she was posting broadsides in the main square saying, “Long Live Bolívar!” On July 17, 1830, she was indicted on several charges, including, quote, “seducing” the palace guards, “insulting the public” and “dressing like a man” which “broke the rules of modesty… [and] morality.” A warrant was issued for her arrest, and the government wanted her exiled. She evaded this for several weeks, but eventually agreed to cooperate with the official order for exile; this may have been less because she wanted to cooperate with the government and more because local Santanderista extremists had begun making assassination threats against her. Violence was escalating in Bogotá around this time. She probably wanted to get out of the city anyway.

37:36 In late August, Bolivarian forced overthrew the Liberal forces, leading to the resignation of the Liberal president Mosquera. In September, several members of Bogotá’s powerful met to call for Bolívar to return from exile and resume power. He was due to return in December, and asked for Sáenz to be there to meet him.

37:53 There were rumors by this point that he was hopelessly ill, though. Sáenz refused to believe this, regarding them as, quote, “mere Liberal propaganda.” In a letter to a friend, Sáenz wrote, quote, “the Liberator is immortal.”

38:07 On December 17, 1830, Bolívar died at a friend’s house, ultimately succumbing to the tuberculosis that had long plagued him. The news traveled slowly, and it’s likely that Sáenz didn’t know until early January. His death was officially announced on January 10th by interim president Rafael Urdaneta. For her part, Sáenz postponed her plans to return to Bogotá. There’s speculation about why–perhaps she wanted to grieve alone. Some sources suggest she had begun to suffer from rheumatism and her exile in a much warmer climate had actually soothed some of the early symptoms that she was experiencing.

38:40 Some also say she may have been severely depressed. Her friend, French scientist Jean-Baptist Boussingault, visited her and said that she had tried to die of a poisonous snake bite. She told him it had been, quote, a “science experiment” but he speculated that she had been trying to imitate Cleopatra’s famous suicide.

38:57 With some help from her friends, she eventually emerged from this darkness. Practical matters began to really concern her, namely that without the job as advisor and archivist, Sáenz was really broke. She was also troubled by the direction the government was taking; without Bolívar to rally around the Bolivarian mission had largely collapsed, but a period of partisan reprisals was starting, escalating violence even further than before Bolívar’s death. Sáenz still retained her status as La Libertadora in many minds, and they came to her for help planning rebellions against the Liberal government. Eventually, in 1833, Sáenz was convicted of being a part of a conspiracy to overthrow the government and was ordered back into exile.

39:36 She was able to put off actually going into exile for a while, largely due to her financial troubles. Travel in South America at this time was incredibly difficult, especially along the mountainous eastern coast of the continent. Among members of the upper class, it was common then to, quote, “defray the cost of travel through the sale of merchandise or by acting as a friend’s business agent;” Sáenz was probably hoping to do this to get to Quito, where she still had relatives.

40:02 The government ran out of patience. On January 1, 1834, she was ordered to leave by the thirteenth. When she hadn’t, a group of nearly 20 people–soldiers, police, and convicts–appeared at her door, ready to quote, “carry her off by force, if necessary.”

40:17 What ensued was a standoff. Sáenz ordered the men to leave her property. When they didn’t she grabbed two pistols and said that if they used force, she would not hesitate to shoot. She announced that she was tired of living and, quote, “couldn’t care less about sending a few men to the next world ahead of her.”

40:34 Eventually, the recently appointed sheriff, Lorenzo Lleras, ordered that she be bound. She tried to fight back but was unsuccessful. She was taken to the local divorcio where they could keep an eye on her overnight. At 5:30 the next morning, soldiers led her and her servants out of Bogotá. They picked up supplies in a neighboring town then slowly made their way to Jamaica, probably not arriving until nearly June.

40:57 This unceremonious and violent ouster did not go unnoticed. U.S. diplomat to New Granada Robert B. McAfee noted with awe that it had taken, quote, “a guard of twenty soldiers a whole day to arrest [Sáenz] without killing her… Bolivar’s favorite mistress [was] as brave as Caesar.” End quote. Local critics were less impressed, accusing the government of going overboard and saying that denying a sick woman the chance to say goodbye to friends or receive consolation from a priest was, quote, “not something done among Christians.”

41:32 Now, the rest of her life is kind of disheartening. She lived in exile for over twenty years, never really recovering from this financial instability. When her husband, James Thorne, was murdered in 1847, she did not receive the inheritance she believed she was owed, and instead it went to his two illegitimate children who he’d had with other women after she left him for Bolívar.

41:52 She spent most of that time in the Peruvian port of Paita, a relatively prosperous town thanks to the local whaling industry. There was a good mix of foreign and native-born residents there, including several of Sáenz’s compatriots who had also been forced into exile by changing government tides.

42:07 She did befriend General Juan José Flores after her exile, who remained important in the political scene of Ecuador, which had seceded from Gran Colombia by this point. He was an old follower of Bolívar, who she had met over a decade before. He was still powerful, and she made herself useful to him any way that she could. In fact, according to Murray it was, quote, “not unusual for women [...] who had been widowed or otherwise left on their own to enter into a clientelistic relationship-cum-friendship with a powerful caudillo,” which is Spanish for a military leader. Sáenz needed powerful people on her side, and Flores helped her a lot. In exchange, she acted as a spy among the other exiles in Paita, letting him know what was being said, who was working with who to gain power, and more. She kept him informed of Peruvian politics, letting him know what was happening, or at least what was being talked about, by the other connections she had cultivated back when she lived in Lima.

43:00 In her final years, Sáenz’s health continued to deteriorate. She injured her hip, and lost ease of mobility in her legs and needed a wheelchair to get around. But at least this time was peaceful for her. The political turmoil and violence that had marked the 1830s largely left her alone in Paita. Toward the end of June 1856, Manuela Sáenz contracted a severe illness, probably diphtheria; there was an epidemic going on. She died as a result of her illness on November 23rd, 1856.

43:29 Like many victims of the diphtheria epidemic, Sáenz was buried in a mass grave outside of Paita. Many people have made pilgrimages of a sort to Paita to see where Sáenz lived out her life and died. Thanks to the work of several South American journalists, novelists, and filmmakers, her life has become iconic in South America. Even famous Chilean poet Pablo Neruda wrote a poem dedicated to her memory titled “The Unburied Woman of Paita.” I’ve included the poem, in Spanish and in English, in the Unruly Figures Substack, so go check that out.

43:57 In July 2010, she was symbolically reinterred in Venezuela at the National Pantheon, where Simón Bolívar’s remains rest as well. Today she’s seen as a feminist heroine.

44:07 And truly, Sáenz’s life signals a unique place occupied by literate upper-class women in early Republican South America. Traditionally, social norms dictated that upper-class women were barred from traditional occupations and expected to stay home to limit their contact with the “corrupting” outside world and public sphere. But Manuela Sáenz found a middle ground between public and private. As Sarah Chambers, historian at University of Minnesota, noted, “although women were excluded from formal politics and the press, they were active in social spaces between the public and private spheres, where philosophies were discussed, plots hatched, and alliances formed.” Sáenzcontributed to a growing respect for women as political agents in their own right. Today, the Museo Manuela Sáenz in Old Town Quito contains personal effects from her and Bolívar in order to, quote, "[safeguard] the memories of Manuela Sáenz, Quito's illustrious daughter.”

Well, that’s the story of Manuela Sáenz! I hope you enjoyed this episode of Unruly Figures. If you follow me on Twitter, you know this episode is a few days late because I had surgery on December 7th and it really knocked me out for longer than I was expecting it to. Thank you all for your patience! If you aren’t following along on twitter yet, why not? We have a good time. Our handle is @UnrulyFigures. Come hang out!