Joe Carstairs: Transcript + Photos

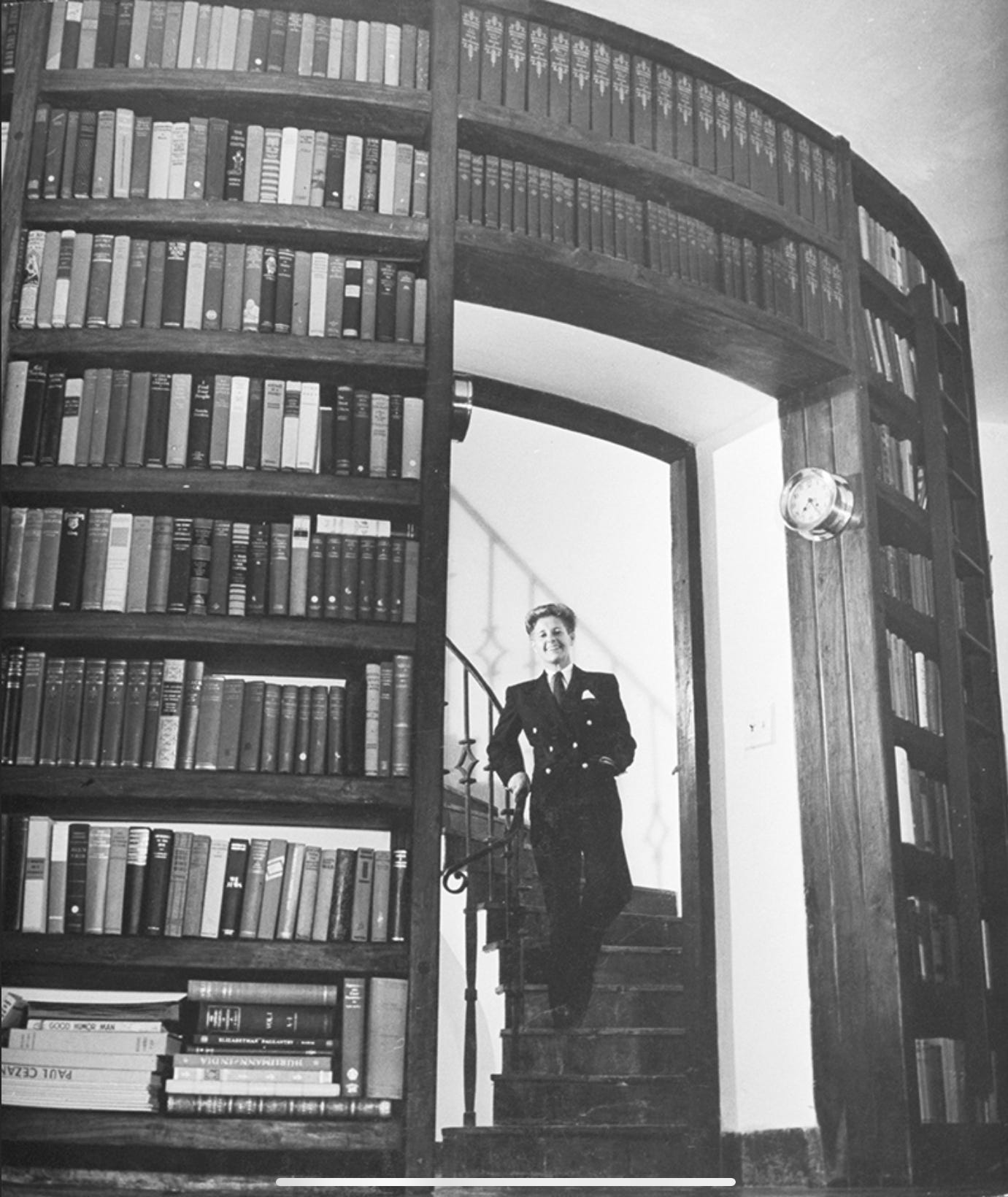

See Joe in her famous beret, meet Lord Tod Wadley, and so much more.

Hi everyone!

Thanks for your patience as I put this transcript together. It took much longer than I thought it would, so I’ll be starting earlier next time. These are the perils of trying new things! I hope you enjoy the transcript and these awesome photos of Joe from over the years.

Looking for the bibliography? It’s part of the episode!

Joe Carstairs episode transcript

0:06 Hi everyone, welcome to Unruly Figures, the podcast that celebrates history’s favorite rulebreakers. I’m your host, Valorie Clark, and today we’re going to talk about famous boat racer Joe Carstairs, an unruly woman if there ever was one. She’s remembered as a World War I ambulance driver, a speedboat racer, a lover of actress Marlene Dietrich, and the owner of an island in the Bahamas. At every point in her life, Joe did things differently than anyone else. She was one of the few women in boat racing in the early 20th century; even when she essentially became an imperialist and de-facto ruler, buying and developing an entire island with a population in the Caribbean, she still broke every expectation of how that was done.

0:45 According to many, Joe was a bit of a mystery. She never liked to reminisce, she didn’t share her feelings very often. She once said, “I never felt anything about myself, I was just it.” Consequently, she was able to do whatever she wanted, unhampered by self-consciousness or concerns about how what she was doing might look to others. Which makes her perfect for my first subject on Unruly Figures.

1:07 A lot of the information I’m going to cover today comes from the only biography of Joe that I was able to find--The Queen of Whale Cay, by Kate Summerscale. For a full bibliography, check out Unruly Figures on Substack--I’ll put the link in the show notes.

1:21 Joe was born Marion Barbara Carstairs in London, England on February 1, 1900. She had lots of names that she used over time, but Joe was the one she seemed to have preferred, so it’s the only name I’m going to use today. Joe was the first child of Scottish Army officer Captain Albert Carstairs and Miss Frances Evelyn Bostwick, an American heiress. The couple divorced soon after Joe’s birth and she never really knew her father. Later in her life, Joe would claim to not even know his name. Some thought that was a joke, and she was known to tell tall tales occasionally, but some allege that Joe was not actually Albert’s child. Evelyn was known to have affairs, so it is possible that this was the reason Albert abandoned his only daughter. Nevertheless, among Joe’s possessions upon her death was a photo of a young man in uniform marked only “Carstairs?” with a question mark.

2:05 Throughout their lives, Joe’s relationship with her mother was strained--Evelyn was a hard drinker and struggled with various addictions. She remarried three times after her marriage to Albert and Joe only ever got along with one of her step-fathers--the third one. The second step-husband, with whom Evelyn had two more children, didn’t like Joe. He found her too ‘wild’ which was very much a euphemism for her masculine behavior even then. Evelyn was also apparently very capricious with her affection, alternately bored of all three of her children or kidnapping them from nannies and boarding schools. Evelyn was especially jealous of Joe’s affection and would fire any nanny that Joe became close to, rendering her childhood really chaotic.

2:43 Maybe it’s because of this troubled relationship with both of her parents that Joe later insisted that her life didn’t actually start until 1905. One day at the London Zoo, when she was just about 5 years old, she was thrown from a camel that had been spooked by a waiter. She was knocked unconscious, and when she came around, she had her first nickname: Tuffy. By claiming this different creation of herself, Joe wasn’t born of her parents but of her own will to live. She rejected the femininity she’d been assigned with Marion Barbara and focused her future with a genderless name that allowed her to self-create outside what her parents and society expected of her.

3:19 Joe didn’t talk about her childhood much. She once told a friend that she never really knew what was going to happen next. She developed a love of boats, though, which became a huge part of her life. Summerscale says in her biography of Joe that she thinks this was the start of a lifelong desire for walled and moated worlds--places that represented autonomy amid chaos.

3:40 When Joe was just eleven, she was packed up and put on an ocean liner, apparently by herself, and sent to New York for boarding school. According to her, this happened because her step-father deemed her too dangerous to be around her young half-siblings. She boasted about being a bully to them, in fact, saying that liked to stick pins in her baby brother. This is probably an exaggeration made up to lessen the trauma she must have felt being more or less dismissed from her family. Much later in her life, she wrote a one-page autobiography and listed this moment simply as, “Left family aged 11,” completely inverting who held the power in this situation.

4:15 For all that she claimed the power of “leaving her family,” Joe talked about boarding school rarely as well. Unlike her early childhood though, she implies that this time away was such a happy point that it all blurs together into rose-colored memories. No trauma, nothing to complain about.

4:30 In 1915, Evelyn divorced her second husband and married her third, a man named Roger de Perigny. (And I’m very sorry if I’m pronouncing that wrong. I studied French, but sometimes it still escapes me.) He was a French count and a sub-lieutenant in the 19th Regiment of the French Dragoons. He and Joe adored each other--she once described their relationship as, quote, “I was like his son almost. He thought I was the end.” End quote. By contrast, Evelyn’s second husband had once caught an 8-year-old Joe stealing a cigar from his office and as punishment, he’d forced her to smoke the whole thing. Joe, who had been stealing his cigars for a while by then, smoked it all with a smile. Perigny, on the other hand, offered the 15-year-old Joe cigars. He also introduced her to his many mistresses and took her with him to a Parisian brothel, which Joe thought was amazing. He treated her like a boy, which was what Joe wanted. She thought he was, quote, “the greatest charmer of all time.” End quote. Importantly, Perigny also introduced Joe to racing. He adapted his personal racing car, a Peugeot, so that she could drive it. This set her on a path that she would continue down for many years.

5:36 It’s relevant to note here that Joe was wealthy, and came from a hugely wealthy family. Her mother Evelyn was the only surviving child of Jabez Abel Bostwick, who helped the Rockefellers become household names. He got very wealthy alongside them and later had a bit of a railroad empire of his own. After his death, his wife Nellie set aside an annual income for Joe that totaled around $145,000, or $2.6 million in today’s money. And so even though Joe worked, especially early in her life, she didn’t need to. And having this access to extreme wealth freed her up to openly embody a very masculine lifestyle at a time when it would have been extremely frowned upon. Had she and the family not been wealthy, she wouldn’t have been safe to live the way she did.

6:19 As you probably remember from high school history class, World War I had broken out in Europe by this point. While tensions had been rising for a while, war was set off with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie on June 28, 1914. The war accelerated and grew, and two years later, a 16-year-old Joe Carstairs decided she wanted to go to war. She begged her grandmother, Nellie Bostwick, to let her go. Nellie, it turns out, was as determined as she was wealthy and managed to persuade the American Red Cross to send Joe to drive ambulances in France.

6:49 Now, this isn’t an unheard-of position for women in World War I--but Joe was one of the first women to do it. The American Red Cross’s actual Motor Corps wasn’t established until February 1917, in conjunction with the National League of Women’s Services, and they only operated stateside. Joe, on the other hand, reached Paris to help drive ambulances before America even formally entered the war in April 1917. Such was Nellie’s reach and influence.

7:14 Joe moved to an apartment in a neighborhood on the north side of Paris called Montparnasse. She lived there with four other ambulance drivers and they got the apartment very cheap because it had a glass roof, and they could see bombers fly overhead. Paris was heavily shelled during World War I and they honestly were fortunate to survive. Later, Joe would recall that she was driving an ambulance in Place de la Concorde, in central Paris, when an aircraft was shot out of the sky. She picked up the pilot, a Frenchman, out of the wreckage, and found that he was already dead.

7:43 It was in Paris, at the age of about 17, that Joe first fell for a woman. It was one of her roommates, a woman named Dolly Wilde. Yes, she was related to Oscar Wilde. The famous playwright was Dolly’s uncle. Dolly was five years older than Joe, and the difference really was stark in Dolly’s self-confidence at that point. Paris was a bohemian, sexually open and accepting city in a way that nowhere else in Western Europe really was. Dolly flourished there, but Joe really remained on the periphery of this culture. She described herself as “too nondescript” for the sophisticated Parisians, she was plain and a stocky American girl. She had the taint of new money and wasn’t really accepted in the Parisian scene. But she was hugely impacted by it, and she and her friends in Paris would go on to create a version of this life in London in the 1920s.

8:31 Joe would later credit Dolly with teaching her to think. She cited her as one of the four women who changed her life. Among other things, Dolly taught Joe that by recreating herself, she could transform her “gauche American habits” into charm. Both of them strove to give the impression that they had invented themselves, not been born of human mothers. For the rest of her life, Joe really embraced the theatricality that Dolly had embodied.

8:53 Now, at the same time that Joe was in Paris, so was her mother. Evelyn was on her fourth and final husband at this point--a French surgeon of Russian heritage named Serge Voronoff. Before marrying him, Evelyn had actually been appointed his lab assistant at the prestigious College de France. This, coincidentally, made Evelyn the very first woman admitted to College de France, though she was not the first woman to complete a degree there. I won’t spend a bunch of time here, but it is worth noting that Voronoff and Evelyn’s research was a bit strange. They did experiments using the glands of animals to treat wounds on humans and claimed that the--and I’m very sorry about the phrase I’m about to say, but it’s the phrase they used--they claimed that the, quote, “testicular pulp” of monkeys had remarkable healing properties in men who were either injured in war or had become impotent in the course of aging. The scientific community was rightfully skeptical of them, and Voronoff stopped receiving grants and financial investment, but Evelyn was able to financially support their research on her own. No one knows if they were fraudulent, or incompetent, or delusional, but they kept up their work despite skepticism from their colleagues.

9:58 Joe never discussed this work. She was known to really hate Voronoff, and would even later in life claim that he was a murderer, and possibly even murdered Evelyn. Her relationship with Evelyn was already strained, of course, but while they were both living in Paris they hardly saw each other.

10:13 However, at some point in 1918, Evelyn got wind of her daughter’s same-sex affairs and summoned Joe to her rooms in Paris. There, according to Joe, Evelyn told her, “I know about you… You are a lesbian. I’ve heard all about it.” She put her foot down--Joe had to marry a man, or she would be disinherited. Joe would always claim that she basically told her mother to go to hell, however, she very quickly married a childhood friend, Count Jacques de Pret, to secure the inheritance. She apparently split the $10,000 dowry with her friend, and they annulled the marriage as soon as Evelyn died in 1921. That dowry, by the way, is worth about $181,000 today, so you can see Jacques really got a lot out of this. Jacques was known as a bit of a ladies’ man and he used his share of the dowry to pay off the bills he’d run up spending on women. Joe went out and bought two expensively tailored khaki uniforms for herself.

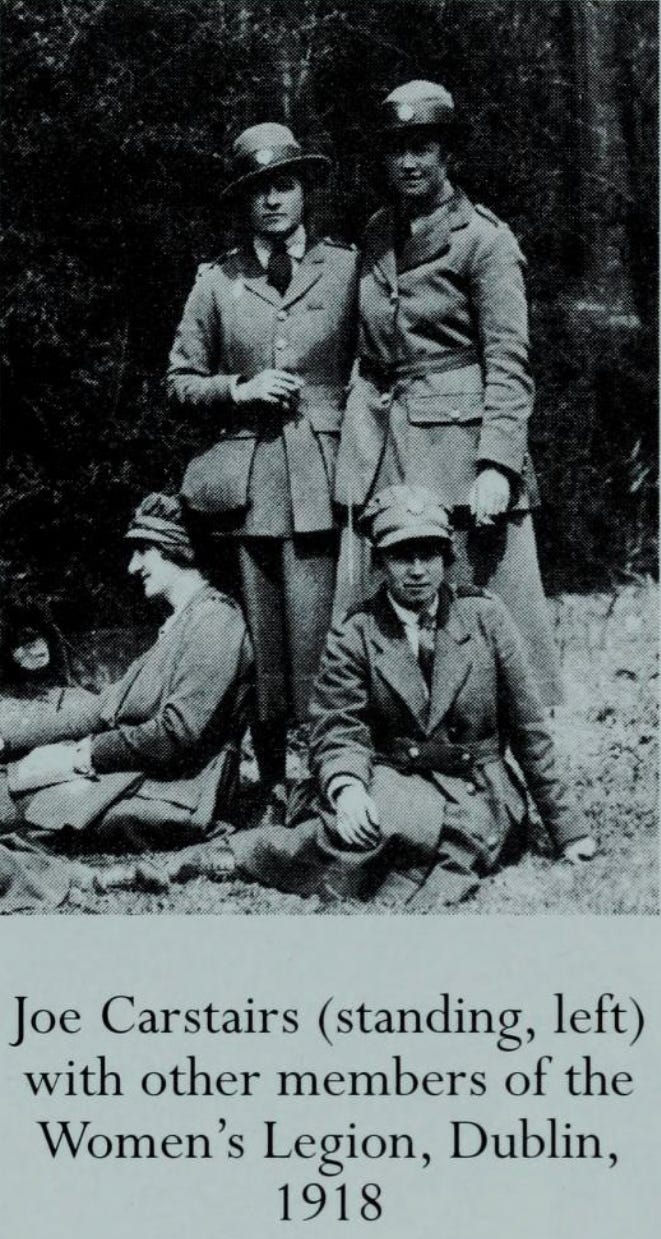

11:09 Soon after her marriage of convenience and once the war was over, Joe looked around for her next adventure and found one waiting for her in Ireland, where Sinn Feinwas waging a guerilla war against the British. Joe enlisted in the Women’s Legion Transport Section, which was a band of about forty young women serving as drivers to the British officers.

11:27 There, she became friends with Barbara and Molly Colecough, who had both been educated at a convent but were too adventurous to go full-time.

11:35 It must have been a strange time to live in Ireland. There was an uneasy truce going on between The Volunteers, later known as the Irish Republican Army, and the British military. The work that Joe and the Colecough sisters did could be dangerous--the Volunteers ambushed military officers’ cars and pelted them with hot tar, but Joe never really reflected on this in her later life. Instead, she focused on the adventures: poker games and sneaking out of barracks to steal a Sinn Fein flag. In early 1919, Joe volunteered with a dozen of the Dublin drivers to go back to France and relieve male drivers. Though the war was over, battlefields still needed clearing, prisoners-of-war still needed supervising, and hospitals still needed help. They drove ambulances, taking wounded soldiers from battlefield medical tents to larger hospitals. They also ferried Chinese labor battalions and German prisoners-of-war to and from work--which was basically slavery.

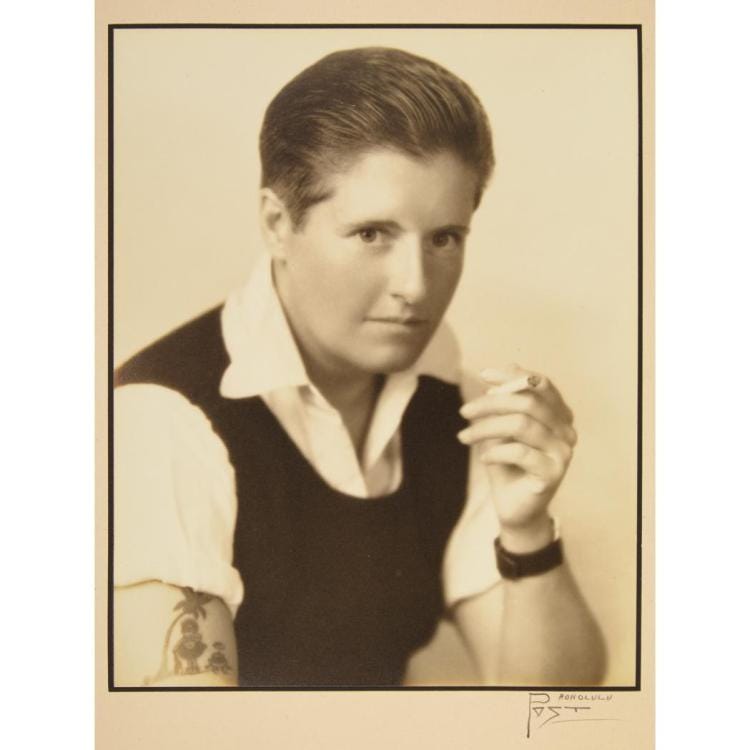

12:25 While in France, Joe was able to adopt an even more masculine identity than ever before. While she’d been expected to wear skirts in polite society, while driving in France she was able to wear a boiler suit to work on her cars. Her uniform included a blue beret, which she continued to wear through the 1920s.

12:40 Adopting the more masculine clothing would have been really necessary for the girls, because driving would have required more than just skill--the land they drove over was destroyed by the war. Some hills had lost as much as ten meters in height from shelling. Roads were full of craters, and fields were churned up, full of sunken artillery, barbed wire, and abandoned trenches. The tires of the cars they drove were frequently punctured and their brakes often gave out. The women were expected to do their own repairs. A dress was not an option.

13:08 In 1920, when they were relieved and sent home, that skill with cars gave them the means to survive on their own. Though Joe and the Colecough sisters floated around for a while, making money with odd jobs where they could, Joe pooled her family money with a few female friends who also knew cars to set up The X Garage in 1920.

13:25 There’s a weird note to make here--in the early 1920s, Joe played at poverty. After her grandmother, Nellie, died in April 1920 (Joe’s mother, Evelyn, was still alive at this point), Joe claimed to be penniless. She took odd jobs during this time, as a bartender and a demonstrator in a Bugatti showroom. She worked briefly on a chicken farm, and claimed to have to steal food from shops to survive. But as I mentioned earlier, she definitely had at least that $145,000 per year, plus whatever she earned working. And when Nellie died, she was worth $30 million with only two people standing to inherit: Evelyn and Joe. (And that $30 million, by the way, is the 1920 figure; in 2021, that was worth $458 million.) At no point was Joe impoverished. The idea was a complete fantasy, either to make herself more likable or just to keep living in that wartime mindset of self-sacrifice. It’s a little upsetting, but here we are.

14:19 In any case, Joe was in London in the early 1920s, which was an ideal time for a woman like Joe to be living there. There was a sentiment after the Great War that women had evolved in response to the absence of men in everyday life. Men had gone off to fight, and many had returned injured and incapable of working again; hundreds of thousands didn’t return at all. The UK government in 1924 put the total military dead at 743,702 people. There was an additional total of 1,675,000 people wounded just from the British Isles. This decrease in able-bodied men in the population meant that there was not just room but an extreme need for women to step in and take over the roles that adult men had held before the war. It’s also key to remember there were close to a million more women than men in Britain at this time, and so to some extent they were seen as, quote, “superfluous women,” who would always find it difficult to marry, so they might as well kind of try their hand at working traditionally male jobs. Women even took up men’s image in fashion--a Daily Mail headline in 1921 ran ‘Healthy young girls are more boyish than boys.’

15:23 Fashion became increasingly androgynous--waistlines on dresses dropped, erasing the image of female bust, waist, and hips. Women’s hairstyles got progressively shorter too--a bob first, then a shingle (which was long bangs but nearly shaved at the nape of the neck) and then most daringly to an Eton Crop, which was completely indistinguishable from a boy’s short haircut. Men’s clothes started to be adapted for women too: blazers, ties, cufflinks, dinner jackets--all of these were adapted for women. There was a fashion called the Oxford Bag, which were pants with very wide legs that removed all hint of the female body.

15:56 Joe loved this. She kept her hair in the Eton Crop style, and wore the Oxford Bag pants. Despite her masculine energy and appearance though, Joe actually never accepted the label ‘butch’ or, as it was sometimes called, ‘a stomper.’ Reflecting on her look later, Joe felt that boyishness gave her a sense of lightness. She said, and I quote, “I did look like a boy, I really did. But I was not a stomper.”

16:17 The X Garage, which Joe started with the Colecough sisters and a fourth woman named Joan Mackern, was a chauffeuring business set up in the heart of Kensington. It was named X, Joe explained, to indicate that it was ‘an unknown quantity’--which I just adore, because it seemed to imply that they knew this could be a risk, socially. They bought a handful of Daimlers, which were luxurious cars with very sumptuous seating. They produced a brochure, which they passed out at all the hotels and theatres. It featured a woman at the wheel of the car, dressed in a jacket, cap, and tie. It proclaimed the woman all—It proclaimed the women all very good drivers because of their time driving for officers in the war, and that they all spoke French, Italian, and German in addition to English.

16:55 The business was a success, for a while. The women took tourists on expeditions to Imperial War Graves cemeteries in France and Belgium. They offered touring holidays to Ireland, Wales, Devon, Cornwall, and the Scottish Lochs. The 1700-mile tour of Ireland took 20 days and cost 134 British pounds, which covered the expenses for five passengers, including accommodations. That’s about 2,000 British pounds today. For laughs, or maybe for tears, as you’ll see, I looked up a similar tour of Ireland today. For only ten days driven around Ireland to see all the sites, it would cost you 1,700 British pounds...per person. For five people to go on a ten-day tour of Ireland it would cost about 8,200 British pounds. So it was a really good deal back in 1921, and I bet it was a lot less touristy too.

17:44 At X Garage, they had notable clients, including James Barrie, the author of Peter Pan, and the Sultan of Perak, which is part of Malaysia. But the novelty of a female driver really confused some passengers. They weren’t sure if their chaffeuses were servants or equals, and it created a lot of confusion when they arrived to pickup their charges from homes and events. This confusion of status, of course, delighted Joe. She was already a woman often in the costume of a man, and also an heiress in the costume of a servant. When she drove, she was at the service of her customers but also very literally in control of them. As drivers they could be rented out with the car for weeks at a time, but they also had a level of independence that other women of their era could only dream of. In newspapers, the ‘garage girls’ were photographed in oil-stained boiler suits, grinning as they changed tires. Joan Mackern told the press that they had employed both men and women but, quote, “found that girls are much more adaptable and trustworthy,” end quote, and so they only kept female drivers. They were a new generation of the New Woman that feminists like Sarah Grand and Henry James had written about in the 1890s.

18:48 Of course, cars were more than a job to Joe. She loved them, she had since she was a teen. At the estate she lived at near the Colecough farm in Hampshire, she had garages where she kept multiple cars for her personal use. It was also around this time that she got more into boating. She had probably known how to sail since she was a kid, but in the early 1920s she bought her first mechanized boat, a yacht she called Sonia. She began racing boats, and was quickly recognized as a talented yachtswoman. In 1924, Sonia took almost every cup in her class. It’s worth noting that Joe was such a rare phenomenon as a female speedboat competitor that there wasn’t a women’s league for speedboat racing. There was one league, and Joe raced alongside men, often as the only woman in an entire competition, a lot of which she won. She was uniquely talented on the water. When you Google Joe, her talents as a speedboat racer are what she’s remembered most for.

19:41 To design her boats, Joe hired a man named Samuel Saunders, the head of a boat building firm on the Isle of Wight, and the inventor of the revolutionary Consuta method of hull construction, which I hope means something to someone out there because it means nothing to me. The hydroplane he designed was a 1.5 liter, ‘Z’-class with a shallow hull. The wood was reportedly so pliant that it gave when pushed on, which seems really dangerous, but what do I know? (I truly know nothing about boating.) Joe named her Gwen, after the Variety star Gwen Farrar, who was one of Joe’s lovers.

20:12 In 1925, Joe took part in the Duke of York’s trophy, a world-famous motorboat race only conceived of the year before. She took fifth place that year--she set the fastest time of the race but got trapped in weeds on the following lap, which kept her from winning. There’s a funny story that Summerscale covered in her biography that I want to share with you. The 1924 winner of the race was a man named John Edward de Johnston-Noad, who styled himself the Count of Montenegro, though no such title actually exists within Montenegrin nobility, and he had absolutely no claim to that noble line anyway. But I guess it was a bit harder to fact-check in the 1920s, so no one cared. Anyway, “the Count of Montenegro,” Johnston-Noad took to Joe. He described her as a “small, dumpy, twenty-four-year-old tomboy, who wore short, clipped hair and dressed like a man… The actress Gwen Farrar was only one of many lady friends. I shall always remember Carstairs’ tough-faced secretary ‘Fatty’ Baldwin--otherwise known as Ruth--cheerleading an ever-changing bevy of attractive girl supporters--each of them smartly dressed and given their own motor car.”

21:13 Johnston-Noad has to be exaggerating this a little. No one else claimed that Joe had a fleet of girlfriends, each with their own car, though she was known to give cars as gifts to some of her friends. I’m sure in the 1920s this was all considered very complimentary, to build her up to the other men, but I think a hundred years later we can take it with, like, a whole handful of salt.

21:33 Anyway, Johnston-Noad (and I hope I’m pronouncing his name correctly. The second half is spelled N-O-A-D, and I saw some pronouncing it as ‘node’ and some as ‘no-ad’)—In any case, Johnston-Noad had the honor of piloting the Duke of York, the future George VI, around the Thames while the other competitors were getting ready in 1925. Joe had created a bit of a stir when she showed up, newspapers called her the ‘new type of river girl,’ and the Duke wanted to be introduced to the so-called ‘river girl,’ which really makes it sound like she was, like, living in a cave next to a river, doesn’t it? So they approached Joe in her boat, but little did they know that her engine had actually just stalled out. Joe, nervous that she would be disqualified if it looked like she was accepting help, shouted at Johnston-Noad and the Duke of York, to, and I quote, “Fuck off! Fuck off! Don’t you bloody well come near me!” Apparently, this bewildered the Duke of York, but they left her alone.

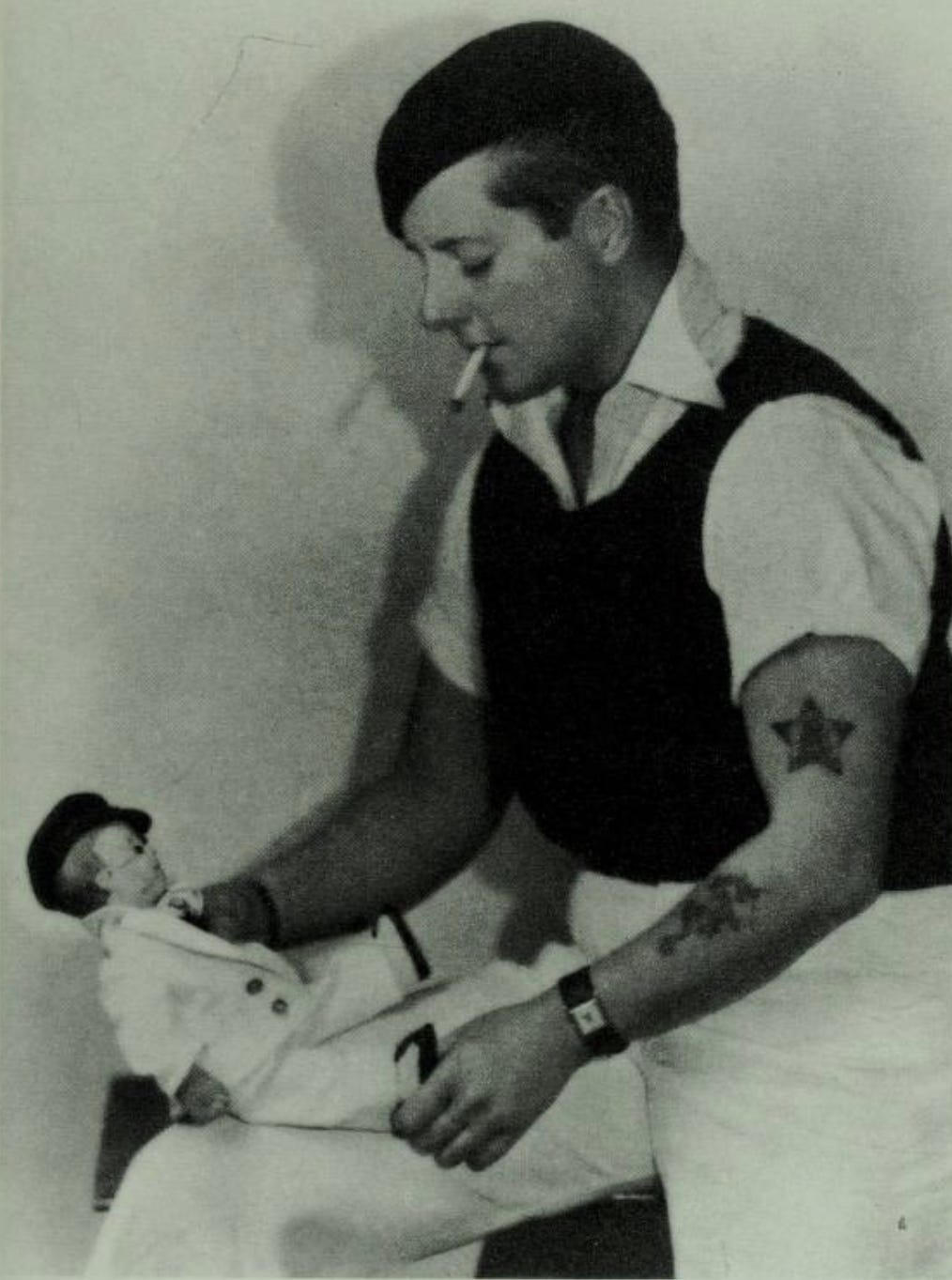

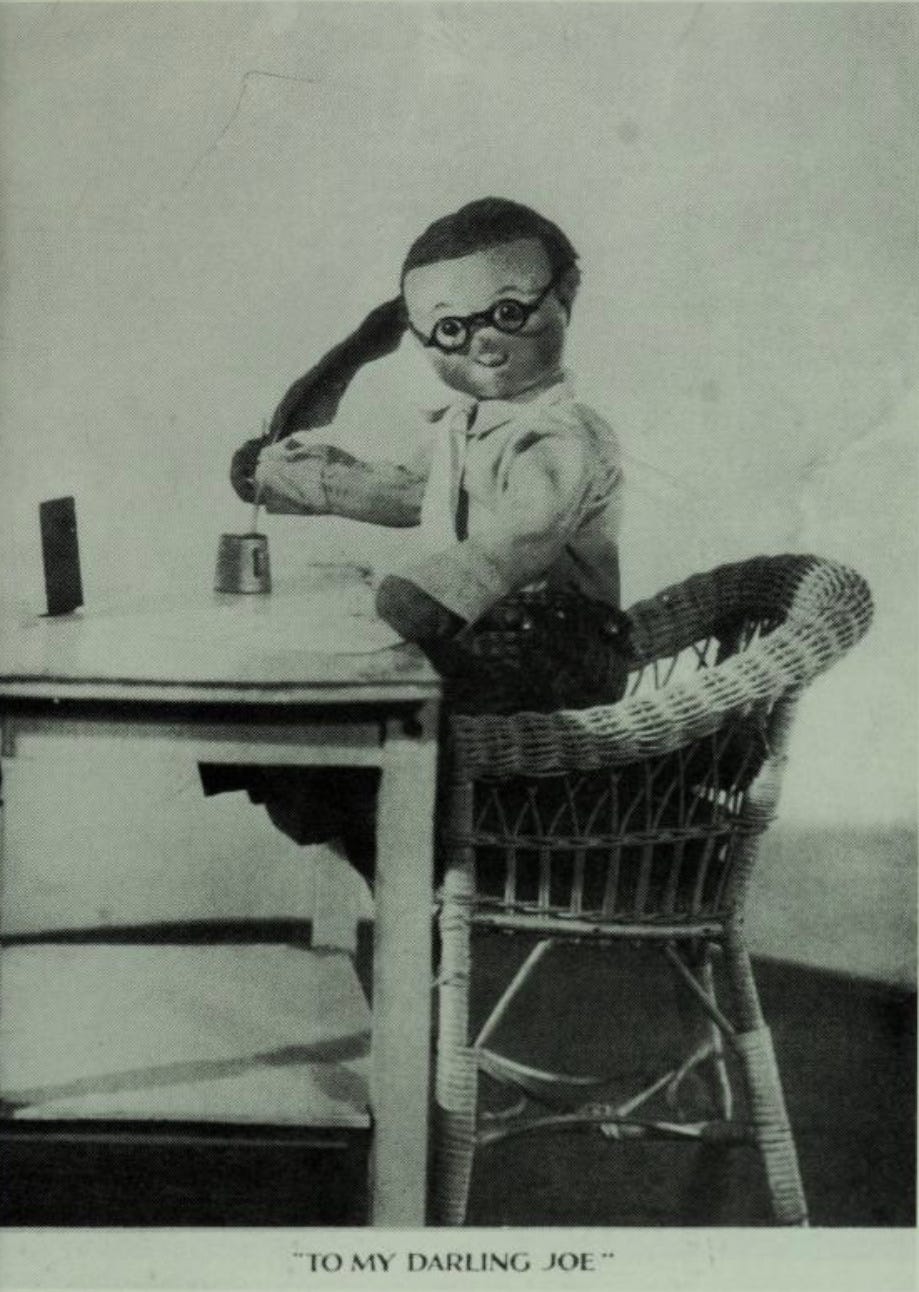

22:35 Now, I hope you remember that name Ruth Baldwin, so cruelly called ‘Fatty Baldwin’ by Johnston-Noad. There’s little record of Ruth, which is a tragedy because she was Joe’s longest relationship, and the girlfriend that Joe probably had the most intimate relationship with. (Which is why it’s unlikely that she was a secretary ferrying lovers to Joe at a boat race, as Johnston-Noad claimed.) At the end of 1925, Ruth and Joe took a trip to the Swiss Alps. For Christmas, Ruth gave Joe a doll--a stuffed leather manikin that stood just over a foot high and was manufactured by the famous toymaker Steiff. His limbs were jointed, so he could be turned and posed in lots of expressive ways, and the soft leather of his face was contoured. Joe named him Lord Tod Wadley, and would love him dearly for the rest of her life. She bought him little tailored suits on Savile Row, and even had his name added to the plaque at her home’s front door in Chelsea, implying that he was alive and could be called upon there. You might think this is a bit weird--Joe was an adult, and not a very feminine one, so on first glance it doesn’t seem like a doll would be a gift she would love. But as Summerscale points out, the novel Nightwood by Djuna Barnes might contextualize this gift for us. As the narrator says, “When a woman gives [a doll] to a woman, it’s the life they cannot have, it is their child, sacred and profane.” Lord Tod Wadley wasn’t just a doll--he was the child that Joe and Ruth would never be able to conceive.

24:01 Now, many motorboat, car, and aircraft racers at this time carried mascots with them for luck. Joe would occasionally refer to Wadley as a mascot, but she never risked taking him out on the water with her. He might have been good luck for her though--the following year, in 1926, Joe won the Duke of York’s Trophy. She went on to win the Royal Moto Yacht Club International Race, the Daily Telegraph Cup, the Bestise Cup, and the Lucina Cup. She was the most celebrated female motorboat racer in Britain, and called ‘the fastest woman on water.’

24:33 Around this time, Joe got drunk one night (or, as she described it,“awfully scratched”) and decided to get her arms tattooed. She then sat with Wadley for a photo: she sat in profile, showing off her new tattoos of stars and dragons, a cigarette in her mouth and a beret on her head. Wadley sat on her knee, meeting Joe’s gaze with a child’s smile.

24:53 Throughout the 1920s, Joe and Ruth threw parties in nightclubs, aboard Sonia, and at their house in Chelsea. These parties were so riotous, that the neighbors actually petitioned to have the women evicted. It was not uncommon for every guest to end up nude by the end of the night. Now, for wealthy women at this time, there was an option to move in social circles were promiscuity and homosexuality were seen as chic and daring. So even though Joe and Ruth lived together through the late 1920s, they also both openly had numerous affairs with other women, and I’ll touch on some of those later.

25:24 In 1928, Joe travelled to Detroit with Ruth, Wadley, her mechanic Joe Harris, and a group of friends. She was there to race in the Harmsworth Trophy competition, which she took very seriously. In the lead up, she stopped drinking and physically trained for two hours a day, putting on about ten pounds of muscle. Once in Detroit, she posed with Wadley for the American press and came out of it really… like, hating America. The American press ran articles where they refused to call her Joe or acknowledge her masculine appearance, instead insisting on referring to her as quote “Betty” and describing her as, quote, “the pretty English motor-boat racer.” End quote. Nevertheless, she did well in Detroit, thereby establishing herself as the fastest woman on water anywhere in the world.

26:09 These issues with the press were a symptom of the larger way the popular tide was turning against women like Joe. As I mentioned, in the aftermath of World War I, masculine women with plucky attitudes were celebrated as helping society recover; eight years later, these same masculine women with plucky attitudes incited anxiety and fear. Some, including Summerscale, blame two fictional works of art for this: Radclyffe Hall’s novel The Well of Loneliness and the movie Pandora’s Box, both released in 1928. Hall’s novel apparently overly sexualized well-to-do women who dressed in men’s clothes and took female lovers. Pandora’s Box included the first predatory lesbian ever on screen. According to Summerscale, these two works of fiction forged a connection in the public mind between the ‘mannish woman’ after the Great War and the dangerous characters of these stories. But there’s no way that one book and one movie created this backlash; it’s more likely a combination of dozens of things. Homosexuality was still hugely disparaged in the UK and the US, that had never gone away. And, at least to me, it seems obvious that as a new generation of men aged into the roles their fathers abandoned for war, they found that women weren’t really ready to give up those roles. It’s hard to shake 15 years of independence and financial security, and so the demonization of these women became a tool to secure the futures of these boys.

27:33 Unfortunately, the X Garage may have been a victim of the changing tides. It closed in 1928, run out of business by Daimler, the company that made their cars. Daimler had started its own touring company, with male drivers, and people preferred it.

27:45 England, especially, by the late 1920s had gone through rounds of celebrating new gender roles only to then have a backlash against them. Oscar Wilde was famously celebrated for a decade before he was suddenly the most demonized man of his generation and put in prison for having same-sex affairs. This pattern of moving forward and stepping back is a pattern of history, especially within the histories of gender roles and sexuality. When I did my master’s degree, I studied the emergence of sexual identities in England and continental Europe in the 1880s to the 1910s and I saw how people would go from being accepting to rejecting and back to accepting based on what was going on in the larger picture of society.

28:23 So while I hate to read it, it’s no surprise to me that in the late 1920s, there was an increase in fear that lesbianism was, quote, “an epidemic”! In 1929, a woman was imprisoned for living under the name Colonel Barker. At her sentencing, the judge explained, “You have set an evil example, which, were you to go unpunished, others might follow.” End quote.

28:42 Sportswomen, who had been so celebrated five years before for liking wholesome adventures in nature, were suddenly accused of indulging in dangerous, feverish excess. The Daily Mail, which in 1921 had run the headline ‘Healthy young girls are more boyish than boys,’ in 1929 began running headlines saying ‘Our girls are too strenuous. Are they overdoing it at sport? Expert’s warning.’ The article commented on the supposed relationship between athleticism and lesbianism. It was concerned with sexual promiscuity, and described it as quote, “over-keenness,” saying girls would quote, “get the fever,” and described lesbianism as quote, “a jolly life--but it may be a dangerous one.” So, you know, the Daily Mail has always been more or less tabloid garbage.

29:26 In 1930, this all began to impact Joe. Instead of being forever celebrated in the press, a distinctly sour note entered articles and reporters perceived her as sinister. Characteristics that had been ignored before suddenly began to note character flaws. One journalist wrote, quote, “She smokes incessantly, not with languid feminine grace, but with the sharp decisive gestures a man uses.” Even her boats, which had been hailed for clean, beautiful design suddenly were described as quote, “powerful but ugly,” end quote, despite not being changed at all.

30:00 She continued racing, but really never met with the same success she had earlier in her career. By 1931, Joe had actually largely given it up, and that year she left on a round-the-world voyage with Lord Tod Wadley and a manicurist, Mabs Jenkins. Over fifteen months, they visited Cuba, Hawaii, New Zealand, Australia, Bali, Singapore, and India, among others. It was India that Joe remembered most dearly later in her life. (And it’s not a coincidence that she believed that her father had died fighting there.) She and Mabs, who Joe nicknamed Kip, hunted in India, killing a panther each, as well as a crocodile they had stuffed and shipped back to England.

30:36 While on their trip, they were assisted by a Sri Lankan man, who is for some reason unnamed everywhere, which is super racist of the historians who came before me. Joe never forgot him though, and she supported him and his financially for the rest of his life. Before he married, he asked ‘the Respected Miss’ for permission to do so, and every year for the rest of his life he sent her boxes of tea. (He was not the only person Joe would financially support for life--Joe Harris, her mechanic, also had an income from Joe for life, as did Bardie Colecough, one of the women she’d served in Ireland with and who had been part of the X Garage.)

31:10 Once she was back in England in the mid-1930s, Joe was a bit unmoored. Her relationship with the press continued to be fractious, and her relationship with Ruth was running into trouble. Ruth had begun drinking very heavily, and was using heroine and probably a lot of cocaine. Joe hated it, because it reminded her of her mother Evelyn’s drug abuse, and so she often travelled back and forth between London, where she lived with Ruth, and New York, where she lived with a woman named Isabel T. Pell, a doctor’s daughter who Joe had a relationship with. Ruth of course hated this, and it caused her to spiral more dangerously.

31:42 In late 1933, Joe saw an ad in an American newspaper offering an island for sale in the British West Indies, now of course called the Bahamas. She sailed over to see it, and bought Whale Cay for $40,000, or $840,000 by today’s rates. She left England for good at this point.

32:00 Since I noted her financial situation earlier, I’ll just update this here: She was receiving about 1,000 pounds per week from her trust funds, but claimed to be over $100,000 in debt, because she had paid no taxes at all in Britain or America throughout the entire 1920s. 1000 pounds in 1933 is worth about 73,000 pounds today, and the corresponding $100,000 debt is equal to about 2.1 million dollars today. Given Joe’s earlier false claims of poverty, I personally have my doubts about this debt. Especially because she was able to financially support so many people she loved for so long, and even in the 1930s I just doubt the IRS really allowed people to get away with not paying taxes for too long. As you’ll see, this supposed debt never comes up again, and we never hear about the IRS collecting it, so I have my doubts.

32:50 Whale Cay was one of the thirty so-called Berry Islands. It lies northwest of Nassua and east of Miami. When Joe arrived, the only inhabitants of the Cay were a Black couple who tended the lighthouse. Legend has it that when she arrived, she asked them if they lit the beacon in the lighthouse every night, and they replied, “Only when the weather’s good.” This of course really amused Joe.

33:13 Various… I mean, colonizers, essentially, had tried to settle on Whale Cay before. A Mr. Wilde bought the island in 1906 and tried to farm sisal, a rope-like fiber which any cat parent or boating enthusiast is familiar with. But the conditions weren’t right and he abandoned it. (Wilde, by the way, is spelled the same as Oscar Wilde, but they’re not related.) After Wilde, a hotel group tried to build a holiday resort there, but failed. When Prohibition began in the US, Harold Christie, a real-estate developer, hosted wild rum-drinking parties for Americans who could afford to get there. But of course when Prohibition ended in December 1933, the island lost all of its value to Christie, and it was he that sold it to Joe.

33:55 Whale Cay is nine miles long and four miles wide, with white sand beaches circling the coast. It rises gently from the water, and when Joe moved there, the surface was thick with jungle. Joe set immediately to developing it, hiring seven men from Nassau to help her clear a path and lay a road from one end to the other.

34:12 At first, the Bahamians didn’t love Joe, but she earned respect from them. Unlike the many colonizers throughout history, Joe wasn’t there to steal from them to take things back to Europe. The land she wanted was all but deserted when she arrived, so she wasn’t stealing it from anyone. And she paid her workers--$4 a week for men, and $3 a week for women--the unequal pay seems like bullshit, but here we are. Maybe they weren’t doing the same work, though I doubt it.

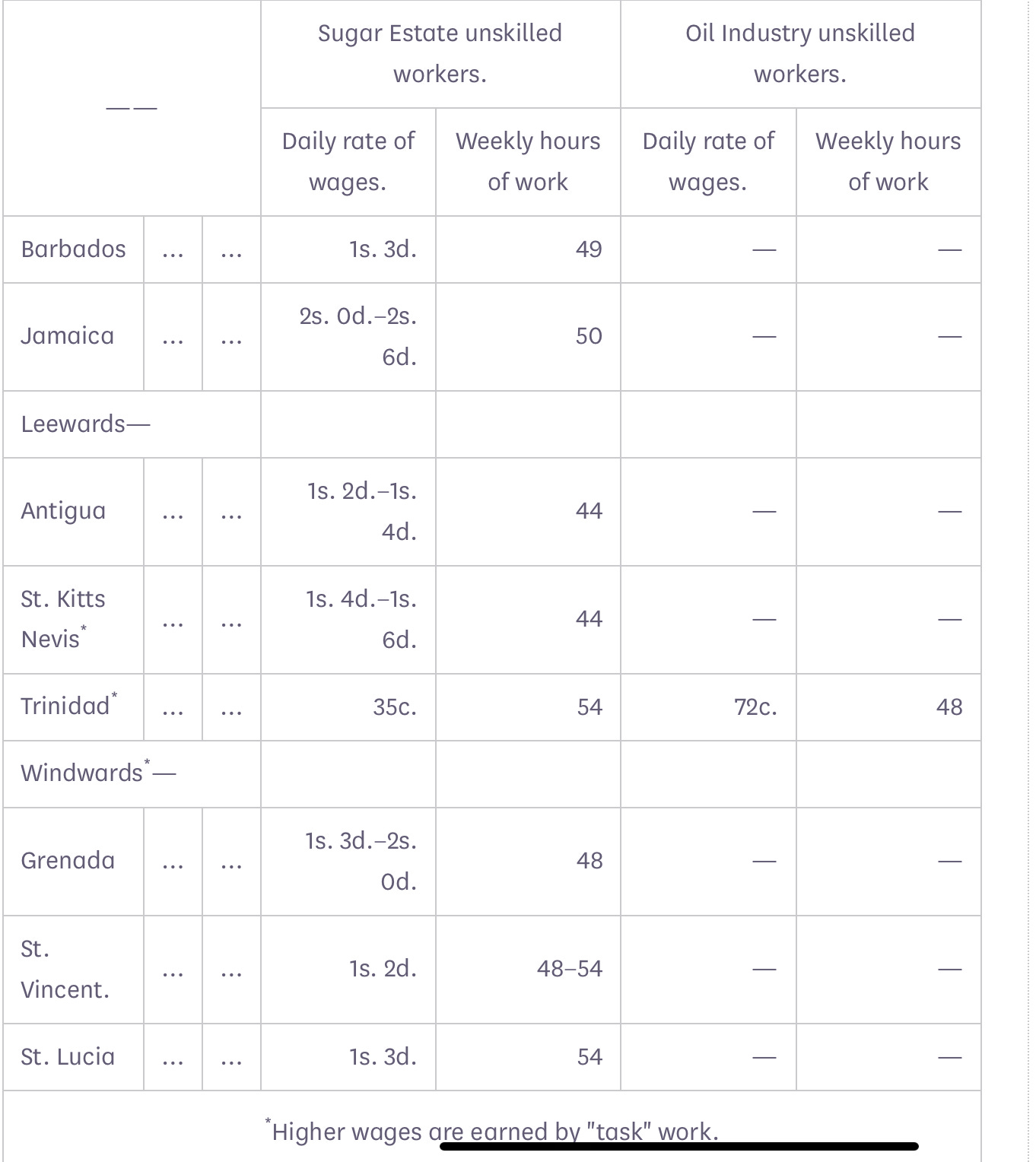

34:40 I want to note this because it’s a way that Joe was treating her employees differently from the way the British government was paying employees in the British West Indies in the late 1930s. Between 1934 and 1939 they had several bouts of unrest brought on in large part by the low wages they were paying their sugar plantation workers. As a reminder, Britain had enslaved the Caribbean peoples until the 1830s. Treatment of them had obviously improved some after slavery ended, but a hundred years later wages were still incredibly low. I found a transcript from a House of Commons debate on February 9, 1938, which included a wage table showing how much money workers in the oil and sugar industries in the West Indies were paid daily. The numbers vary by island, but sugar estate workers could be paid as little as 1 shilling and 2 pence per day or as high as 2 shillings and 9 pence per day. People probably worked 6 days a week with rest on Sunday, so that range calculated weekly looks like 7 shillings per week, which is less than half of one British pound, to around 16 shillings and 6 pence per week at the very highest. 16 shillings is just over two-thirds of a British pound. So workers in British government plantations in the Caribbean had to work a minimum of 8 days to earn 1 British pound.

35:54 Now, I couldn’t find a historical exchange rate table dating back to the 1930s. So I can’t say with 100% certainty what the correct comparison is here, but I think it’s reasonable to assume that the 3 US dollars per week that Joe was paying women on Whale Cay was a lot more than the 16 shillings per week the British government was paying its highest earners.

36:13 So Joe’s presence and comparative generosity was a huge financial boon to many. People poured in from neighboring islands to work for her, and many stayed for a long time and made Whale Cay their home.

36:25 In this way, Whale Cay was developed. Twenty-six miles of signposted road was laid and stores were built. Shacks were built for the workers, or they were free to live on the boats they’d sailed over if it was safe enough. Together they cleared coconut groves, planted 3,000 palm trees, began storing fresh water and grains, and developed agricultural fields where they grew fruit and vegetables. Joe had the lighthouse rebuilt, put up a power plant, created a radio station, built a schoolhouse, founded a small medical practice, and established a museum. She became police, judge, jury, and executioner all rolled into one--though to my knowledge she never actually executed anyone. She broke up fights, she listened to arguments, and handed down punishments or rewards. She also established an early version of health insurance: she insisted everyone who lived on Whale Cay contribute to a health care fund, which they then used if anyone needed to receive hospital treatment. If someone died, Joe paid for the funeral herself, so the costs wouldn't have to come out of the family’s wages. At Christmas, she provided drums of wine, and she threw huge wedding parties for anyone who married on the island. The store held a weekly dance which was renowned throughout the islands. So, yes, Joe was a colonist, and an imperialist in many ways, but she also did so much more for the people who worked for her than any other white person had.

37:45 Joe designed a home for herself at the southern tip of the island that three hundred men worked on. It was a five-bedroom Spanish-style villa with white walls, red tiles, and wrought-iron railings. It was finally completed in 1936, and then Joe turned her attention to buying more islands: Bird Cay, Cat Cay, Devil’s Cay, and more. She and her employees established huge crops of fruit and vegetables on those islands as well, which they exported. Joe built a harbor on the north end of Whale Cay, where they built a schooner.

38:15 And so, Joe recovered from the way her adoring fans had turned against her in England. She worked hard, but she also gave her workers the entire months of July and August off. During those summers, she took herself on vacation to Europe or the US, which is how in 1938, she began a relationship with the famous actress Marlene Dietrich. They shared a heady, clandestine affair that we only know about because Dietrich’s daughter, Maria Riva, wrote about it in her biography of her mother. She helped her mother sneak out to see Joe all summer, concealing her absences from both her father and her mother’s lover, the novelist Erich Remarque, who was known to be very jealous. Six years later, Remarque used both Marlene and Joe as characters in his novel The Arch of Triumph, but makes Joe a man in it.

38:58 Joe was so infatuated with Marlene that she offered Whale Cay to her, population included. Marlene declined, but did actually accept a beach; the deed to it was found among her possessions when she died. After their summer together in Europe, the two visited each other: Joe to Hollywood and Marlene to Whale Cay, but their relationship eventually soured. Marlene accused Joe of a theft, which Joe denied. Joe recommended an assistant to Marlene, who Marlene accused of theft also; it would later come out that the assistant sexually assaulted Maria, though neither Marlene nor Joe knew of it at the time. It was the one end to a relationship that Joe seemed to hold a grudge about. While other women were forgotten as easily as they were met, Joe had a lot to say about Marlene even later in life, alternately calling her, quote, “a wicked old woman” and saying that she was, quote, “the only person who might get me.”

39:48 Soon after the summer with Marlene, Joe started opening up Whale Cay to the wider world. It was a short boat trip from Miami, so she would throw parties there and invite scores of people for riotous events on the island. She screened films, held enormous poker games, and invited people to hunt goats.

40:03 In 1940, the Duke of Windsor was made Governor of the Bahamas. It was an attempt by the British government to shuffle him and the Duchess off the international stage during World War II. When he had sat on the throne as Edward VIII, he had been rejected, more or less, for loving Wallace Simpson, an American divorcée, and exiled for offending British propriety. Joe probably saw a lot of similarities in their stories. In any case, the Windsors arrived in Nassau in 1940, and visited Whale Cay in January 1941. They were both very impressed by Whale Cay, and the Duke even reportedly lamented that she was doing better than the government was on its own islands. Soon after, Life Magazine ran a cover story that celebrated Joe’s achievements on the island.

40:44 Now, for better or worse, Joe would sometimes play pranks on her guests, or trick them for her own amusement. With the distance of time, some of these pranks seem really tasteless, but they amused her. She once hired a group of workers to drum menacingly outside the house. Joe convinced her guests that they were rioting--which was not unheard of, there had been uprisings and riots on other British West Indies islands, and people had died in the ensuing violence. She warned they’d all be killed, but promised to try to save them. She went outside and shot off some guns into the air, then returned to say “It’s going to be alright.” It’s unclear whether or not she ever told her guests that they were never in any real danger, and that the whole thing had been staged.

41:24 In a more lighthearted fashion, in every guest room, Joe had a joking notice put up with several rules, like a hotel. However, the rules were absurd. They started with, quote, “Use light switch only when standing on rubber mat provided.” End quote. And continued through with rules like, quote,“Visitors wishing morning tea in their rooms will be dealt with accordingly.” Or, “Do not disturb moths in clothes closet. HATCHING SEASON.” She loved a joke.

41:50 Joe loved disguises too, and she especially loved to dress up as an extremely feminine woman--she would wear ludicrously vivid makeup and don a blonde wig and high heels for shopping excursions in New York. As a friend of hers said, “That was the epitome of a costume for Joe.”

42:04 I haven’t talked about it yet, but I think Joe’s gender identity might be a bit confusing for anyone who has a modern understanding of gender identity and performance. Joe usually dressed in pants and loose shirts like a man, obviously went by Joe instead of Marion or Barbara, and had very traditionally masculine hobbies--boat racing, building, you know, etc. She often passed for a man as well, accidentally or on purpose. But in no surviving record that I’ve seen does anyone say that Joe wanted to be a man, or that she felt like she was supposed to be a man. Gender affirmation surgery, or as it would have been called then, sex change surgery, had existed in Europe since the early 1900s. Joe would have known about that option, and certainly had the financial means to get this surgery had she wanted it. The fact that she never took that route, and that there’s no known record of her expressing any kind of gender dysphoria tells me that she didn’t care about the fact that she was a female. As I said at the top, Joe didn’t spend a lot of time thinking “about” herself, not in that way. I mean, she was obviously self-aware, but wasn’t prone to a lot of reflection, and so I think she was happy as-is. Which, you know dang, I wish we all had the level of self-confidence and ease in our own bodies that Joe did.

44:16 In any case, tragedy struck as well during this time. In August 1937, Ruth Baldwin collapsed at a party in London. She died quickly after, at just thirty-two years old. Though Ruth had refused to move to Whale Cay, it hadn’t actually changed the nature of her relationship with Joe. Upon learning the news of Ruth’s death, Joe and her friend Tim Brooke rushed to London on a French liner to pay their respects and mourn.

43:40 Ruth’s death changed Joe. She began to write poetry, which was a huge shift for a woman who had been so action-oriented her whole life. She privately published two volumes of poetry, in 1940 and 1941, with a girlfriend under the pseudonym Hans Jacob Bernstein. On the surface, the volumes are practical jokes, full of spoof forwards and ridiculous dedications. But the poetry itself, while not amazing, is raw and passionate. They touched on homosexuality, feminism, and death, issues Joe never discussed outloud.

44:12 Perhaps energized by her grief and the new perspective it brought, in 1939 Joe set up the Coloured League of Youth, which was very white savior-y in its aims. She wanted to, and I quote, “elevate the standard of living for the Black people,” which sounds nice on its face, but she put herself in charge of it and also claimed that Black people didn’t care to improve their lives themselves, so she needed to help them. Which is obviously still quite racist. Through the CLY, Joe encouraged people to live sober, healthy, moral lives. Her rhetoric was utopian in a lot of ways, but her actual plans were rooted in making the Bahamas more agriculturally viable. Economic growth had stalled for the last several decades, largely because the white politicians in Nassau, known as the Bay Street Boys, made their money on importing things, so they were actively disincentivized from promoting local growth. Joe wanted to challenge their power. The league was altruistic, but it was a bid for her to extend her empire. Whale Cay was doing so well that she wanted to prove that she really ought to be in charge of all of the Bahamas.

45:14 She did give each member of the league a farm on Bird Cay, if they wanted it. For one year, Joe supplied new farmers with free food, clothes, beer, cigarettes, seeds, tools, fertilisers, and advice on farming. They received vouchers for the market instead of wages--it was sort of like an internship, with room and board. After a year, the free supplies would be taken away, but they kept the land. The farmers could sell whatever they grew and keep all the money. Part of her goal was to teach people to be completely independent and not rely on others for wages, and this was one way that was actually successful.

45:50 I think it’s important to note that, outside of the CLY, Joe doesn’t seem to have a white savior complex about the way she treated every Black person she encountered. Joe dated Black women, and befriended many as well, though she never dated anyone who worked for her. When she took a particular liking to kids on Whale Cay, she mentored them, though sometimes she resented them when they grew up and left the Cay. In the early 1950s, she worked with a Black priest from Nassau to establish a summer camp for underprivileged boys on Whale Cay. Joe provided them with all the transportation and accommodations and they came back each summer for thirty or more years.

46:23 As World War II heated up in 1940, Joe was eager to be a war hero again. In August 1942, she got her chance. The American ship Potlatch was torpedoed and sank near Nassau. Weeks later, Joe was called on to mount an expedition to find and rescue the survivors. She went out on a yacht, without lights or radio, sailing through waters where German U-boats were known to hide. Near where the ship was reported to have sunk, Joe finally turned on lights to search the waters--she found 47 American sailors hanging to the sides of a small schooner. It was too laden down to sail anywhere, so the men had been trapped for thirty days and thirty nights, living off sharks and low-flying birds they managed to capture.

47:06 When Joe got them all on her boat, they drank most of the water and ate all of the food. Several were desperately sick and many had kind of lost touch with reality to some extent. But they made it to Nassau without loss of life. There, they were met by the Daughters of Empire, a group of women headed by the Duchess of Windsor, who were sorrowfully unorganized. Despite Joe having radioed ahead, they didn’t have enough stretchers or enough ambulances on hand. But the sailors survived and a year later they threw Joe a party to thank her for saving them.

47:36 By 1943, most of the local cargo ships working in the Caribbean had been conscripted for the war effort. So Joe began using her personal fleet of schooners and yachts as a transport company, carrying bananas, ice, sugar, and rum to Miami and Nassau.

47:50 Joe was poorly rewarded for this work though. She was accused of being a Nazi sympathizer, which was patently false. But she was desperate to help with the war effort; she wanted to reclaim the glory of driving ambulances in France. She even asked her half brother, Frank Francis (the child of her mother’s second husband) for advice on how to enlist. The two were never close--and would actually begin actively feuding in the mid-1940s--so he unsympathetically told her, “Wrong age, wrong sex.”

48:20 Joe’s feud with Frank did lead to her getting her pilot’s license in 1945. She’d never shown interest in planes before, but Frank had distinguished himself as an aircraft pilot before the war, and Joe was not about to be outdone by him. Her new interest in flying led her to wanting to construct a private airport outside Miami, to serve the smaller aircraft that had been clogging up Miami’s central terminals. But it didn’t work--city government rejected her plans. She tried for three years to convince them, but eventually had to concede that it was never going to happen.

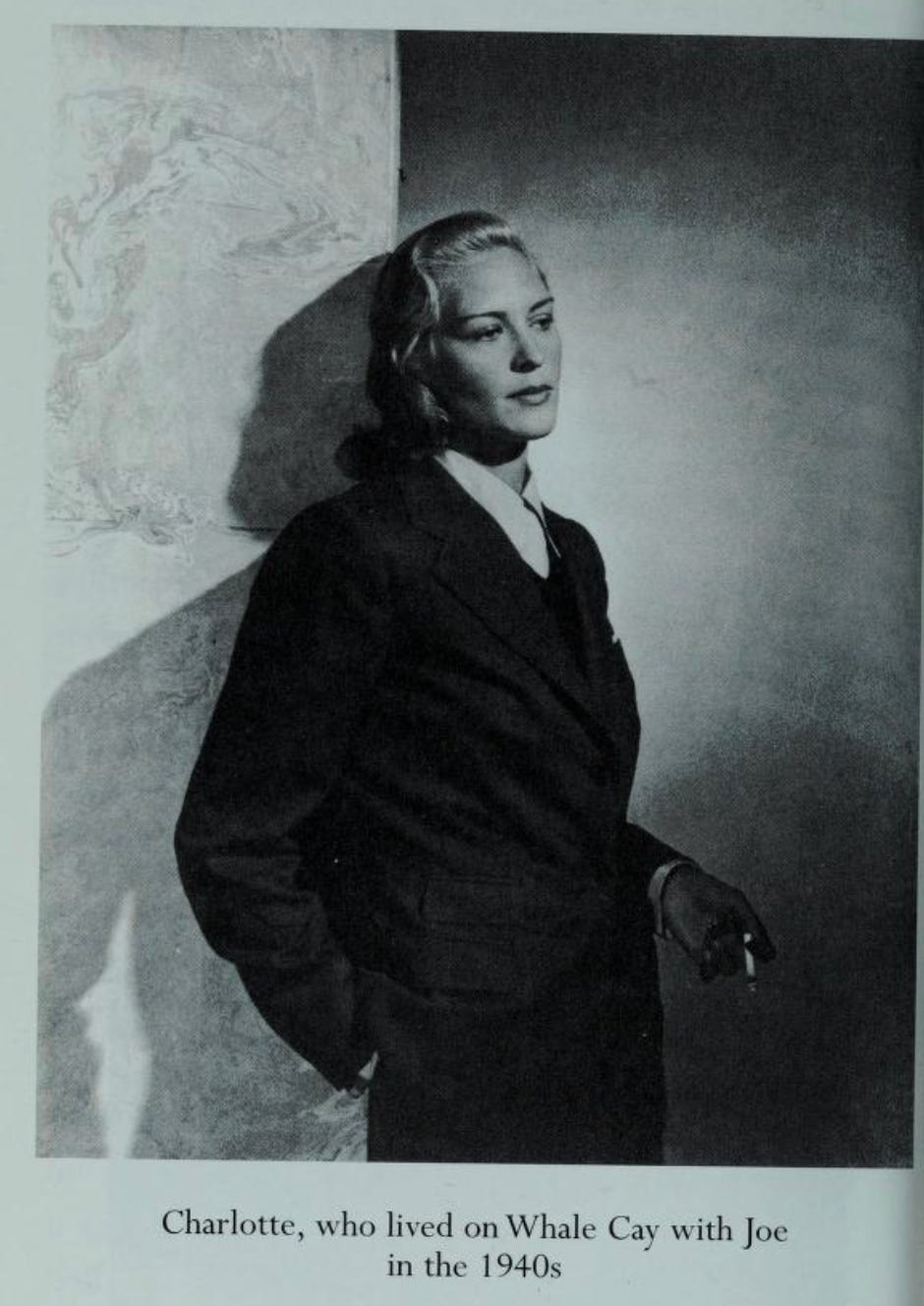

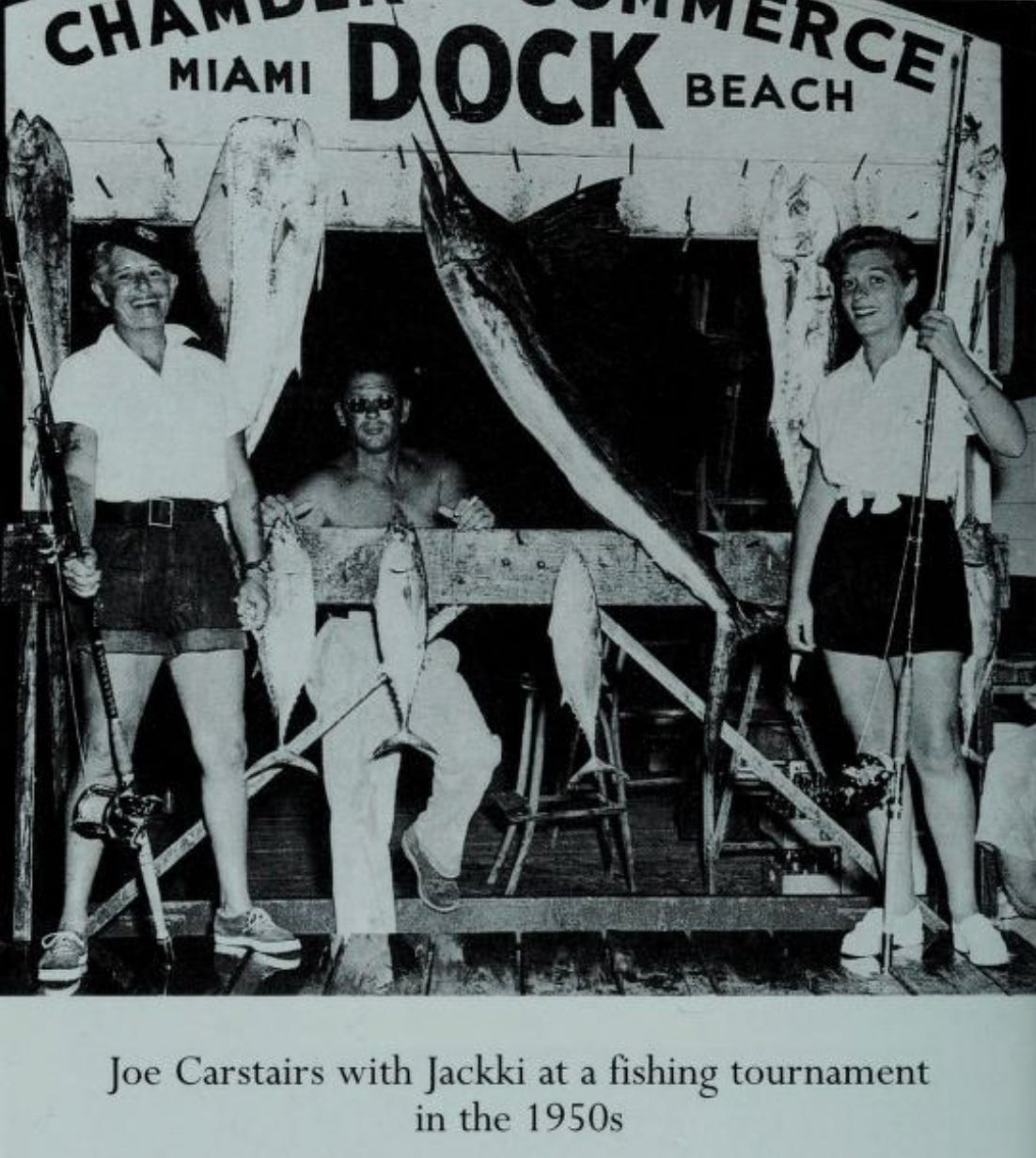

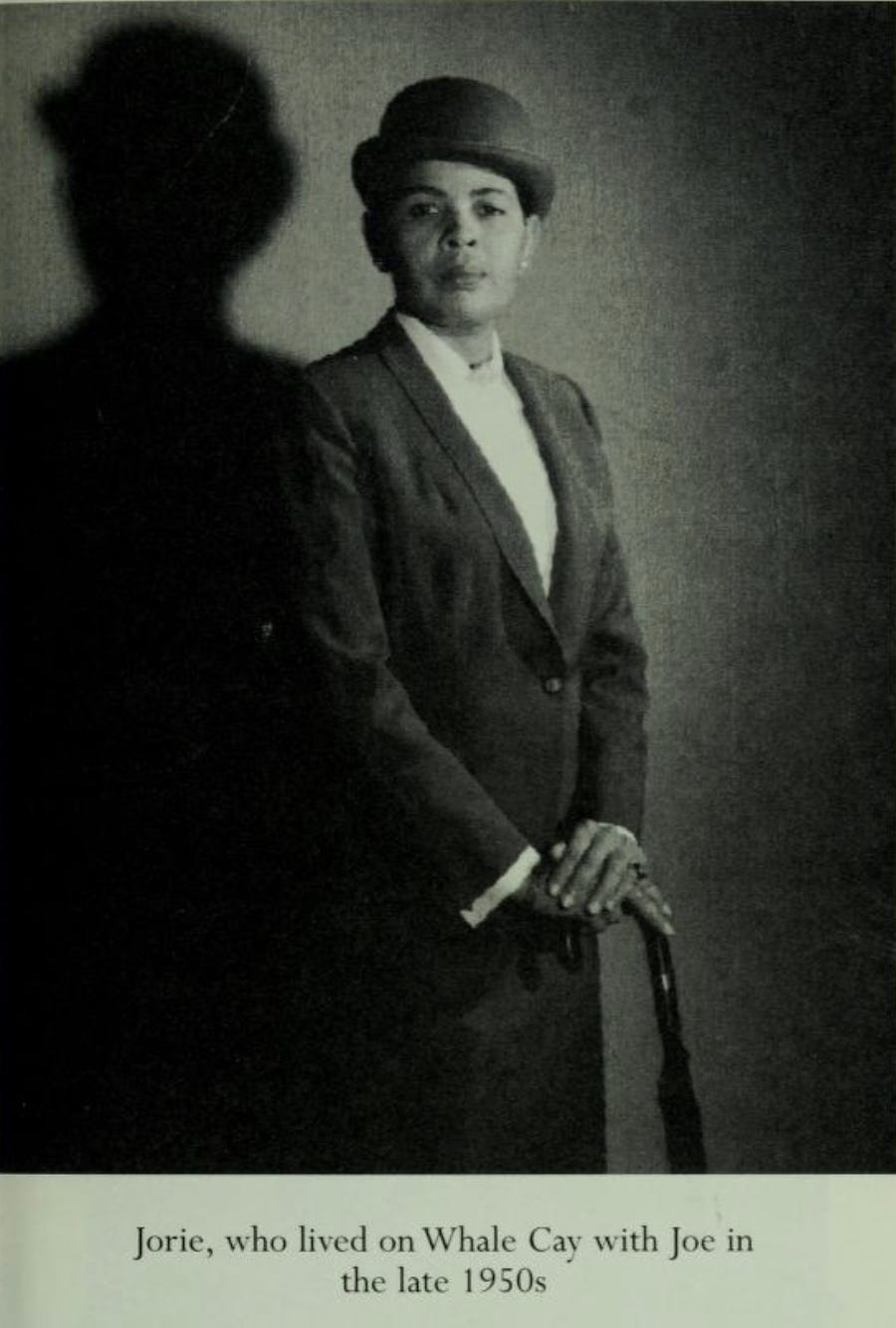

48:50 Life for Joe gets a little less exciting from here, and there’s correspondingly less documentation. She continued to live on Whale Cay after World War II, though the hurricanes made it more difficult. She dated a series of women--first a woman named Charlotte, who lived with her on Whale Cay through most of the 1940s. In 1950, Joe met Jackki, a red-headed New Yorker who was about 25 years younger than Joe. Jackki was remembered by many of the Whale Cay residents as being thoughtful and kind--she took a keen interest in the children who lived there. In 1957, Jorie met Joe at a poker party in New York and followed her to Whale Cay. She was 34 then, the same age Joe had been when she moved to Whale Cay in 1934.

49:29 Joe had long resisted the signs of her own mortality, but they sped up in the late 50s. Her hair turned white, and she started to experience a terrible pain in her legs, which the doctors attributed to arthritis. Eventually, she had to have a hip surgery. She wanted to believe that she was immune to social and historical forces, too, though by my reading she was usually as much a recipient of them as any of the rest of us; she was in the limelight in the Roaring Twenties, went into exile in the much more staid Thirties, and so on and so forth.

49:57 In the 1960s, Black Bahamians gained a degree of independence from Britain, and the islanders still on Whale Cay turned on Joe. Her power had waned as British power had. She began to spend less time on Whale Cay, and in 1975 she sold it and abandoned it completely, though she would always claim this was due to the increase in drug trafficking in the Bahamas. Joe was heartbroken by this, she was heard saying that, quote, “It felt like a woman had died.” She couldn’t bear to see beaches for years afterward. Joe converted a naval supply vessel, the St. Pete, into a houseboat, and she and Jorie lived there on a quiet stretch of the Miami river. Joe remained in Florida for the rest of her life, for a while in Miami, then eventually she moved to Naples.

50:39 By the late 1970s, Jorie left Joe to begin seeing someone else. At this point Joe gave up on romance--in 1978 she asked Hugh Harrison, a man about 15 years younger than her, to move in with her as a friend and paid companion. He did so happily, and stayed with her until she died--her last significant human relationship. Joe became more attached to Lord Tod Wadley, the doll she’d never stopped loving. In fact he began to, quote, “reproduce,” and there were many more dolls around Joe’s home. But Wadley remained special, and Joe used him and his eternal youth almost as an avatar for herself moving forward. In the 1980s, Joe embarked on a property venture in New York, and named the company Wadley Associates.

51:21 In the last decades of her life, Joe changed her will at least twice a year, charting the courses of her relationships through cash. In the final will, the bulk of her fortune, estimated at around $33 million, was split between Hugh, Charlotte, Jackki, Jorie, and other friends. (For those curious, $33 million in 1993 is worth about $62 million today.) She made more than 30 individual bequests to friends and employees who she had taken care of, ranging from $5,000 to $600,000. She discouraged the same friends from visiting her though, hating the idea of them seeing her as she sickened in her old age. She never quite lost her fighting spirit though--she would place bets with Hugh that she would live to see 94, a bet that she unfortunately lost.

52:04 On December 18th, 1993, just six weeks short of her 94th birthday, Joe slipped into a coma. Her nurse placed Wadley in her arms and brushed her hair, then whispered to Joe that it was 9:40, hoping that she would hear the numbers and think she had reached the age of 94. Joe died some time in the night, and her body was taken away the next morning. She was cremated, along with Lord Tod Wadley, and their ashes were buried with some of Ruth Baldwin’s ashes in a tomb by the sea.

52:32 I hope you liked this story about Joe Carstairs--she is so fascinating to me, because she witnessed several hugely significant historical periods, and had a huge impact on the world herself. Joe paved the way for women in motor and water sports, she changed and redirected the economy of the Bahamas, and she did it all while having a lot of fun. She never seemed to worry over her legacy, or how she was perceived, and I think that’s amazing.

Thank you for tuning into the very first episode of Unruly Figures. If you’d like to see photos of Joe, you can check those out on the Unruly Figures Substack, that’s at UnrulyFigures.Substack.com. There you can also become a subscriber to get ad-free versions of each episode. I’ll be back in two weeks with more stories of history’s greatest rule-breakers. Until then, stay unruly.

I have spent many months on Whale Cay over the years. The amount of work Joe did on that Island is staggering in its scale. Sadly it has all but fallen to rack and ruin over the years, but the walls remain. I also have visited her other properties in the Berry Islands as well as a very large tract of land she owned on Andros Island, not far from Neville Chamberlin's family home and birthplace. Joe was an amazing and strong woman and I am very happy to have saved the few surviving small bits of her race boat Estelle IV. I am only sorry I never got to meet her while she was alive. She is still spoken of with great respect by the Bahamians that worked for her on Whale Cay.

Dear Don,

I am currently performing an investigation on Marion Carstairs Harmsworth Trophy racers, in which context I also try to identify the designer of Estelle IV and V (only known as "Bert Hawker"). I have been happily surprised by your comment "I am very happy to have saved the few surviving small bits of her race boat Estelle IV" and I would welcome the opportunity to exchange further on this subject with you. How can I reach you? My email is sebastien.faures(a)yahoo.fr

Looking forward to hearing from you, Sebastien